After the collapse of communism in 1989, Romania was not only politically unmoored, but it also found itself culturally orphaned. The structures that once defined its creative economy, however rigid and ideologically oppressive, dissolved almost overnight. Artists, newly unshackled from state control, were thrust into a world without safety nets: no funding, no institutional support, no functioning art market. And yet, something took root in this precarious ground. What grew out of the cracks was not a unified movement but a porous, ever-evolving ecology of resistance, experimentation, and quiet audacity. Today, Romanian contemporary art is not a footnote to Western discourse; it is an active agent in reshaping it. The contemporary art of Romania does not ask for pity or permission. It is not waiting to be discovered. It is already here, speaking in many tongues, asking better questions, and if we are wise, we will listen.

In order to understand how and why Romania has grown into a vital node in the global art conversation, we must first revisit the conditions from which this emergence sprang. Under Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime, the final communist leader of the nation, visual art held a paradoxical position; it was both lionized and surveilled. On one hand, artists had access to studios, stipends, and exhibitions through the Union of Artists. On the other, the subject matter was expected to toe the ideological line, a form of soft censorship that rarely required outright banning. Until the fall of communism in Romania in 1989, the arts were stuck in a perverse system of support that was both sustained and stifled.

With the abrupt fall of the regime, this contradictory infrastructure vanished. What remained was an aesthetic and logistical vacuum. Influential figures emerged in Bucharest in the early 1990s, confronting the double bind of newfound freedom and institutional void. Among them, Călin Dan played a pivotal role, not only as an artist but also as a curator and institution builder. His work as Chief Editor of Arta Magazine and with the Soros Foundation in the 1990s laid the groundwork for many of the country’s future art platforms. Later, as director of the Muzeul Național de Artă Contemporană al României (MNAC), Dan helped formalize what had previously been ad hoc, pushing his personal mission of stimulating the arts ecosystem in Romania and advocating for its international visibility.

Advocates like Dan were working without institutions. This period was marked by improvisation and solidarity. Informal artist-run spaces and independent initiatives filled the gaps left by the implosion of state-sponsored culture. From this fractured foundation emerged a generation of artists and curators who redefined what it meant to make and show art in Romania.

Here, we saw the rise of the distinctly Romanian phenomenon, the Cluj School. This loosely affiliated group of painters, including artists such as Victor Man, Mircea Sucui, Marius Bercea, Șerban Savu, and others, brought international attention to Romania in the early 2000s. Encapsulating the artists of the transitional era in post-1989 Romania, the Cluj School did not solidify as a term for these artists until 2007, as a result of the efforts of Giancarlo Politi, editor of Flash Art Magazine and organizer of the 2007 Prague Biennale, who showcased a number of these artists flourishing from the turmoil of their time.

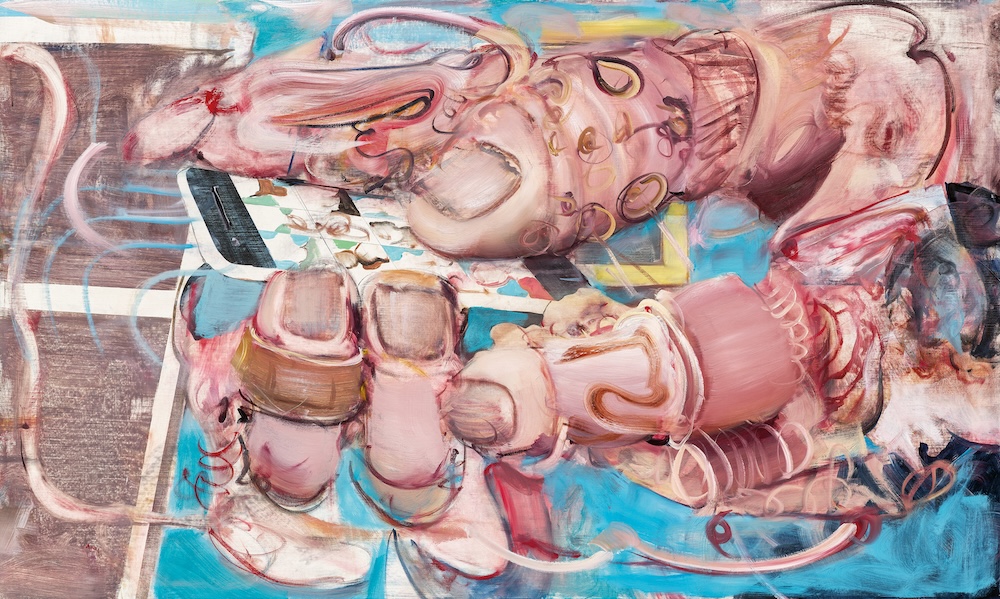

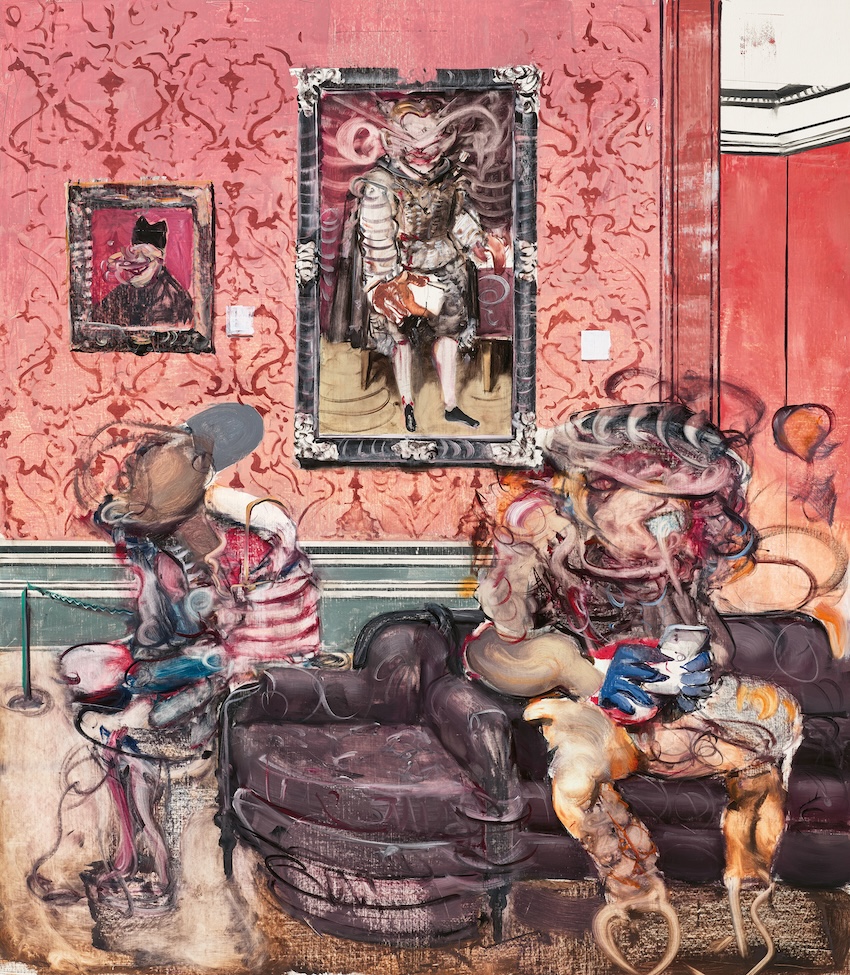

The Cluj School was, in many ways, an anomaly: a painting-centric movement in a time of post-medium pluralism. While many of them studied under professors promoting movements such as Abstract Expressionism, the artists under the umbrella of the Cluj School embraced the representational, the surreal, and the somber. Their work was figurative, moody, and often psychologically charged with loose brushstrokes and darkened palettes. Critics and collectors alike were drawn to its ambiguity, as it was neither wholly nostalgic nor overtly political; it captured something of the psychic residue of post-communist life.

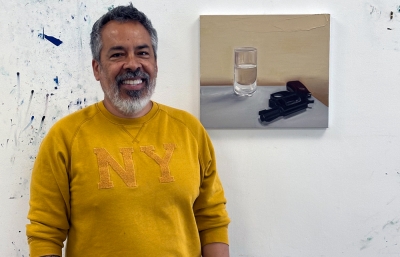

Adrian Ghenie, arguably the most commercially successful of the group, brought a cinematic sensibility to historical trauma. His paintings often feature blurred, distorted figures that evoke both personal memory and collective violence. But to focus solely on Ghenie would be to miss the broader ecosystem. Șerban Savu, for example, offers a quieter, more sociological gaze. His depictions of working-class life in Romania's post-industrial landscapes resist both romanticism and despair. There is a stillness to his work that belies its depth, a sense of watching a society slowly recalibrate itself.

The Cluj School's success on the international stage led to a rapid acceleration of interest in Romanian art. But with visibility came new tensions. Many artists, especially those working outside of Cluj, resisted being lumped into a singular narrative. They wanted to tell other stories, stories that did not solely center on trauma, or the Western gaze.

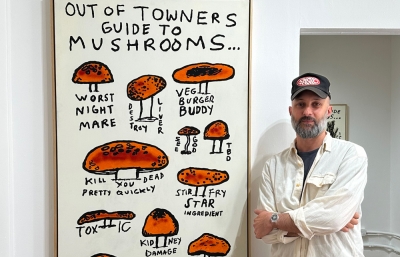

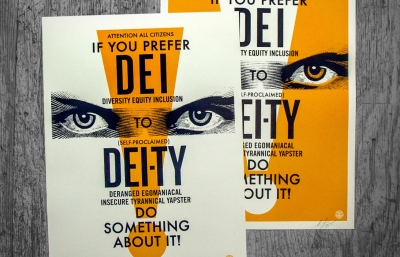

Dumitru Gorzo, for example, occupies a space of productive antagonism. His work traverses genres, incorporating folk traditions, political satire, and pop aesthetics with an improvisational ease. Gorzo's sculptures and mixed-media installations often poke at the absurdities of both nationalism and global consumerism. Nicolae Comănescu, meanwhile, turns the grime of Bucharest into pigment. His canvases incorporate soot, ash, and street detritus, transforming urban decay into a kind of sacred residue with an intelligent humor. Their practices speak to a broader trend in Romanian art, an embrace of materiality, of the stuff of daily life, of what is cast off and overlooked.

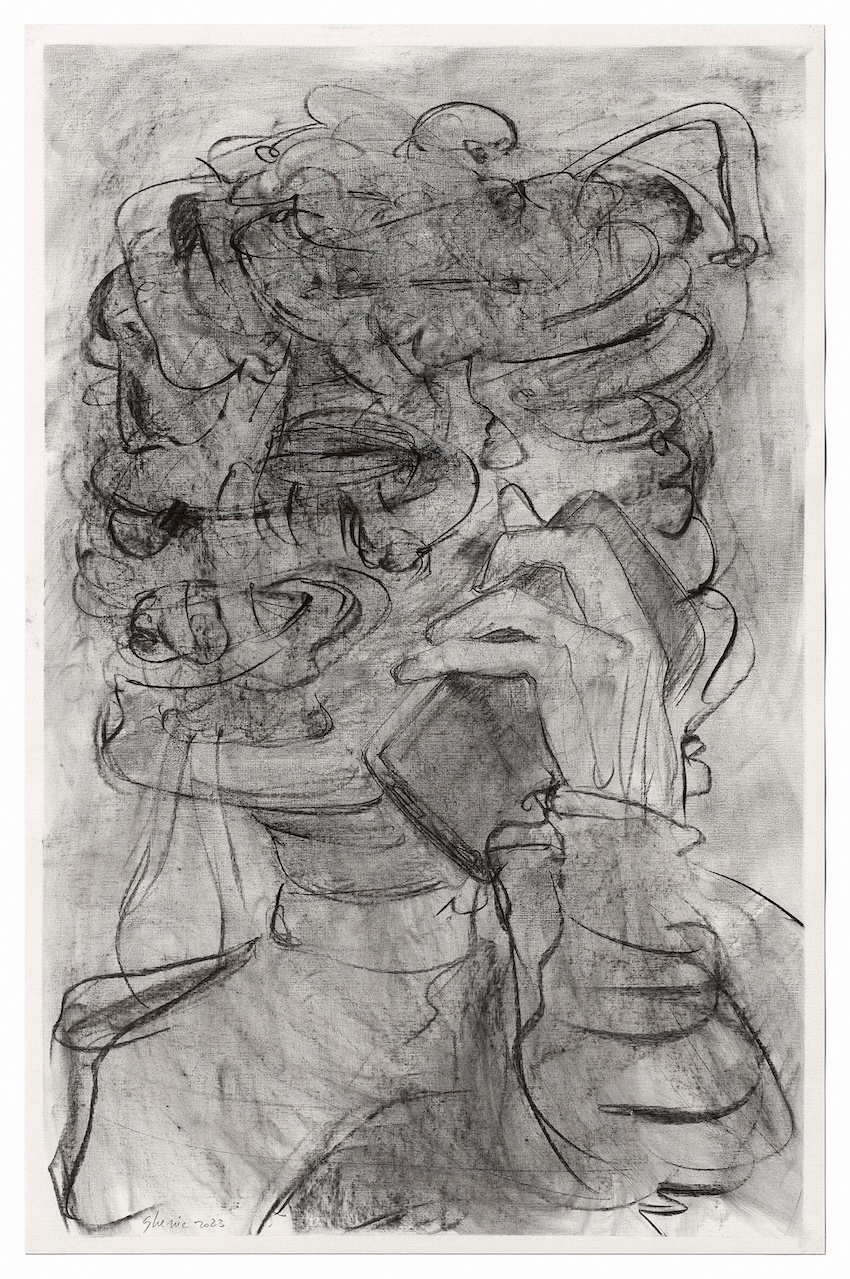

Another artist who complicates the narrative is Radu Oreian. While based in France, the Romanian-born artist studied and honed his craft in Bucharest, going on to share his work extensively across the globe. His intricate, obsessive drawings collapse time and scale. Influenced by the iconography of ancient myths combined with our modern digital aesthetics, Oreian creates microcosms that feel both ancient and futuristic. His work continues to offer a meditation on memory and humanity, proving they are not something fixed but living, mutable architecture.

Female artists, too, have played a crucial role in redefining the field, though, as is often the case with the historiography of art, they have often received less attention in international surveys. Among them is Ioana Maria Sisea, whose use of sculpture and installation explores intimacy, eroticism, and bodily presence at the intersection of capitalism in today’s society. Her work often incorporates soft materials, like wax, textiles, and latex, to question the hard lines between desire and disgust, attraction and abjection, themes that would have easily been censored in the pre-1989 era of Romanian art.

With a rise in artists came a growth in the way they were represented and intermingled with the broader world of art. In 2002, Dan Popescu founded H’art Gallery, the first of Romania’s private art galleries that provided a unique focus on the growing local art scene. Similarly, Catinca Tabacaru Gallery, the formerly New York-based gallery that moved its headquarters to Bucharest in 2020, emphasized exchange. While championing works by Romanian artists, they created new pathways for international artists to be exhibited, notably artists such as Zimbabwe’s Terrence Musekiwa, who has his inaugural exhibit with Art Basel as part of Catinca Tabacaru Gallery. The role of galleries in Romania has also seen the development of crucial institutional relationships. Anca Poterașu Gallery, for instance, was essential in facilitating the acquisition of work by Romanian artist and curator Aurora Király into the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

It was through more than just individual artists and gallerists that the influence of Romanian contemporary art made its way into the international art world. In his curation of the Romanian Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007, Mihnea Mircan, an Antwerp-based curator, posed a compelling provocation: What does a monument mean in the fragmented, ambivalent terrain of contemporary life? Titled “Low Budget Monuments,” the exhibition reimagined monumentality not as an assertion of power or permanence, but as a space of vulnerability, subjectivity, and critical reckoning through works by Romanian artists Cristi Pogăcean, Mona Vătămanu & Florin Tudor, and Victor Man. Emphasizing the increased connections beyond Romania, the acute awareness of broader geopolitical undercurrents, and a subversion of nationalist remnants through architectures of resistance, Mircan curated a space where new forms of collective memory and artistic agency from Romania emerged.

As Romania's artistic output diversified, so too did its infrastructure. The 2010s saw the emergence of a more cohesive art ecosystem, from new galleries to an influx of domestic and international collectors, biennials, and festivals for the arts. One of the most significant developments was the founding of the RAD (Romanian Art Dealers) Art Fair in 2023. A collaboration between Robert Băjenaru, Matei Câlția, Andrei Jecza, Mihai Pop, Alex Radu, Daniela Palimariu, Alexandru Niculescu, Andreea Stănculeanu, Suzana Vasilescu, and Catinca Tăbăcaru, RAD is more than a market event. Now in its third year, RAD has a significant role in telling Romania’s story in the art world while pulling together businesses, such as their title sponsor Banca Transilvania, and community organizations in support of their mission. RAD is a proposition that Romania is not peripheral but central, not emergent but already arrived.

RAD is remarkable for more than its curation but for its atmosphere. It brings together generations of artists, from the foundational figures of the 1990s to the newest graduates of art schools in Bucharest and Cluj. It dissolves the lines between commercial and critical, between celebration and critique. In doing so, it enacts a kind of collective authorship. The fair and its experiences are an acknowledgment that the Romanian art scene is a series of individual careers that come together to construct a shared, ongoing project.

Expanding beyond the infusion of the art fair premise into the Romanian contemporary art world, RAD provides artistic opportunities beyond the commercial. Their Design Initiative, an interdisciplinary dialogue on the relationship of art with objects and popular culture; Curatorial Summit, which brings together voices shaping the global positioning of Romania’s art scene; and Sculpture Park, a public art initiative that exposes the intersections of art and nature under the leadership of Director Alex Radu, signal a renewed investment in art's social function. These spaces invite conversation between disciplines, generations, and publics.

Other initiatives have reinforced this ethos. Salonul de Proiecte, which opened in Bucharest in 2011, expanded the dialogue on Romanian contemporary art through increased connections within and beyond the country's borders. Continuing its work today, it remains a vital independent art space changing the course of cultural discourse through opportunities that emphasize the research and production of art.

In 2018, Spaţiul de Artă Contemporană (SAC) launched within the Romanian art community. Expanding with a second site called SAC Malmaison alongside SAC Berthelot, the arts-based nonprofit has become a key site of experimentation, emphasizing transdisciplinary artistic activation and collaboration. SAC was never merely an exhibition space. It functioned as a laboratory, a critical forum, and a curatorial training ground. Utilizing spaces imbued with historical resonance, here, artists and curators engaged not just with aesthetic questions but with the palimpsest of Romanian memory: surveillance, incarceration, silence.

Documenting and sharing these evolutions with the world came new publications that specialized in the contemporary art of Romania. Among them is PUNCH, a publisher and bookshop based in Bucharest that uncovers the intersections of art, architecture, and design. Since opening their independent services in 2017, they have provided opportunities for not only artists but also galleries and arts organizations to put their work into print. Cărturești bookstore, on the other hand, opened in the early 2000s as a means for building a community around the literary arts and knowledge. They have since expanded their operations to include Cărturești & Friends, which transforms their Bucharest bookstore into a collaborative space for exhibitions and ideas, a hub for building community around the books, arts, and culture of the region.

With an ecosystem of artistic and exhibition production taking shape, the contemporary art scene of Romania witnessed the emergence of a new collector base, further infusing it with energy. Figures like Tudor Grecu represent a shift in the role of the collector, from passive buyer to active cultural agent. Grecu, founder of the Romanian collective ArtCollect, sees collecting not just as acquisition but as advocacy. It is a way to support artists materially, yes, but also to amplify their voices, to build archives, to shape public memory, and to build a cultural community.

This ecosystem remains fragile. Public funding is inconsistent. Bureaucracy lags behind ambition. Many artists still rely on residencies abroad or government funding that breeds self-censorship. And yet, these very constraints have fostered a unique kind of creativity. In the absence of institutional safety, Romanian artists have built their own infrastructures, ones that are flexible, collaborative, and self-aware.

The newest generation of Romanian artists is coming of age in a hybrid world. They inherit the traumas of communism, but they are also shaped by digital cultures, transnational solidarities, and ecological urgency. For them, Bucharest exists as more than a peripheral geography in today’s artistic landscape; it is a site of possibility. To speak of a "Romanian contemporary art scene" today is to speak of an open system. It is not a school or a trend but a set of relations: between artists and curators, between history and speculation, between local textures and global currents. What has emerged over the past decades is a new cultural paradigm, one that embraces complexity, resists simplification, and insists on the value of art as a mode of thinking, remembering, and dreaming otherwise. —Charles Moore