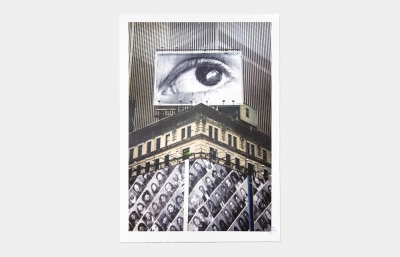

For Khalik Allah, photography is a spiritual endeavor, a conscious marriage of street and self, a quest to elevate both. It is also inherently lyrical, and like a preacher improvising a sermon, a musician in the zone, or poet freestyling off the dome, there’s something mystical and transcendent in the execution. That’s not to say it isn’t firmly grounded in this reality, in the actuality of life at 125th and Lexington in Harlem where much of his work is focused. Cycles of addiction, poverty, and suffering haunt the darkness of this nightscape but the camera is an instrument beholden to the light. Allah has referred to what he does as “camera ministry,” and he applies the salve literally, ushering people out of the shadows and into the light to take a portrait. “When you focus on the light in another, you reinforce it in yourself,” he explains. “And really, that's what I'm striving to do. I'm trying to reinforce my own knowledge of self, which is essentially light. Spirit is light.”

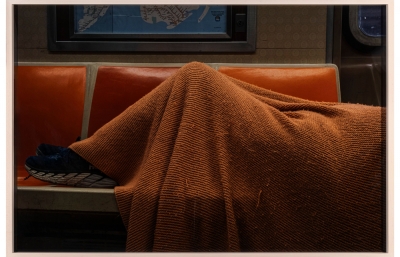

He is a filmmaker as well, practicing his craft in a manner inseparable from his photography. Watching his films is a dreamlike experience delivered in part by an audio track divorced from the visuals. The effect is initially disorienting but serves to sharpen focus on the images and sounds in a way it could not effect otherwise. Unable to assign words to faces, the anonymity of the deeply personal conversations takes on the shape of shared experience and separated from the aural, the visual is heightened in style and effect, akin to spending time with a photograph. Allah’s voice from behind the camera becomes a signature presence as he guides us through the streets. Engaging with new and familiar faces, we listen as he experiments, teaches, learns, and reflects. Process becomes product, and where the artist begins and the work ends are almost indistinguishable. “I believe that the art is equally about the artist as it is about what the artist is depicting. This practice of photography has a lot to do with perception. It's not an objective practice… and I'm about being real and allowing people to understand me.”

Allah is self-taught and builds from personal experience. Every interaction is an opportunity for knowledge. In one of his earliest films, Urban Rashomon (2013), he introduces us to Frenchie, a mentally ill man who becomes a friend and continual subject. At this particular moment, Frenchie is high on K2 (synthetic marijuana), making incoherent noises, drooling to the ground, and posing for Allah’s camera. The scene is uncomfortable and feels a little problematic. But as the film proceeds, and even more so in its follow up, Antonyms of Beauty (2013), he explores an evolving, personal relationship, creating a complex portrait of a man most of us might choose to walk past. Their bond deepens, and as Allah’s practice matures, he lays bare the human habit of conscious and unconscious tendencies towards judgment and bias. “We’re not these bodies that we inhabit,” says Allah. “But my goal as a photographer is to go beyond that. I'm trying to take images like psychic x-rays. I'm trying to deliver a person's soul. I'm trying to go beyond just the physical and I think that all good photography does that.” —Alex Nicholson

Khalik Allah is a Magnum nominee and is represented by Gitterman Gallery in New York. His films Urban Rashomon, Antonyms of Beauty, Field Niggas, and Black Mother are available to stream on the Criterion Channel. His latest, IWOW (I Walk on Water), is available on demand now.