For the Liste Art Fair Basel that opens next week, Martin Kačmarek's “If We Got In” series with Super Dakota continues his explotaion on the intricate relationship between tradition and innovation in agriculture, pulling from his personal experiences growing up on his family’s farm in Slovakia. Throughout the works in the presentation, Martin invites us to consider the complexities of farming today and the deep emotional ties that bind individuals to their land and heritage.

Kačmarek combines airbrush techniques with traditional brush strokes, creating a unique fusion of shapes, colors, and textures. His mastery of the airbrush gives his canvases a sharp, digital aesthetic, reminiscent of rendered images, online spaces, and video games. The figures he portrays, appear ambiguously connected to their surroundings, their linear silhouettes strangely detached from reality. Lighting and color play crucial roles, conveying the passage of time throughout the seasonal practices of farming.

Kacmarek’s works are deeply autobiographical, reflecting on his relationship with his family’s farmland where he grew up. Over the years, he has developed a strong interest in learning about more sustainable ways to care for the land, which he also explores in his paintings. Through the lens of regenerative farming —a method that contrasts with conventional practices— he explores the challenges of introducing new agricultural techniques in a setting bound by tradition.

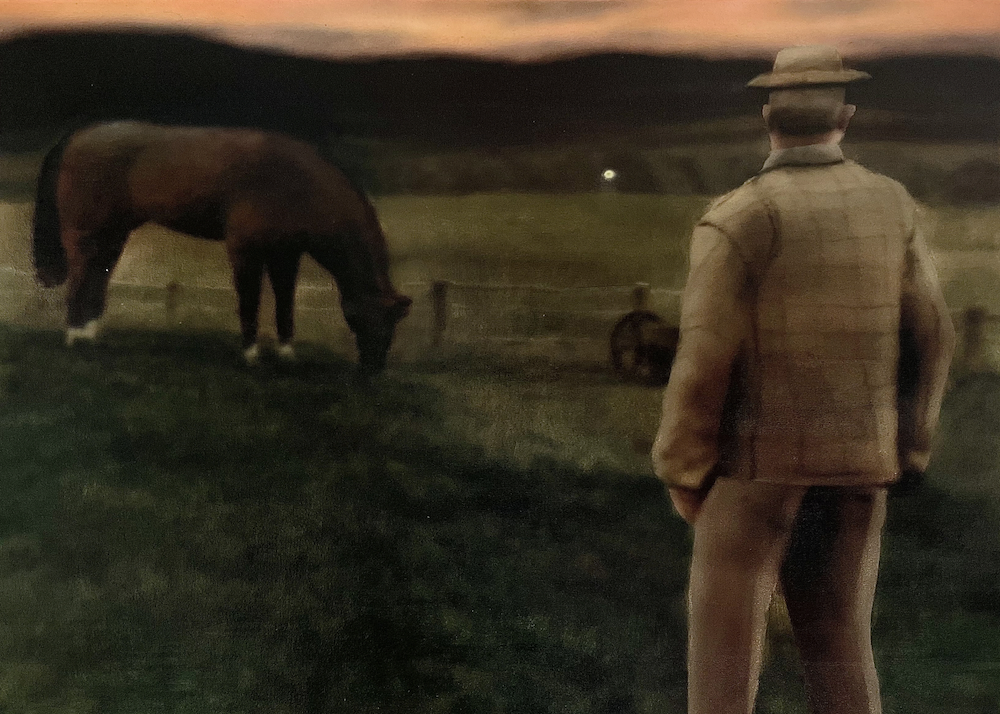

This tension is most evident in works like “The Great Dig in the Sky”, inspired by a Pink Floyd’s song, the motif represents a farmer taking a radical step for his future —burying an old plow used for tilling, symbolizing the foundation of common sense among peasants. It’s a step that, “in our region, represents the future of sustainable soil management”. A common socialist motif —for example, seen in the works of painters like Martin Benka, Mária Medvecká, or Jozef Hanula —often depicted peasants with plows working hard in the fields. Martin’s concept stands in contrast to that. The fight for the future has become more of a fight for the present.

The painting “The Great Dig in the Sky” carries a gloomy atmosphere, meant to evoke a funeral for the past. It ties into the principles of regenerative agriculture, where not plowing the soil is a fundamental practice.

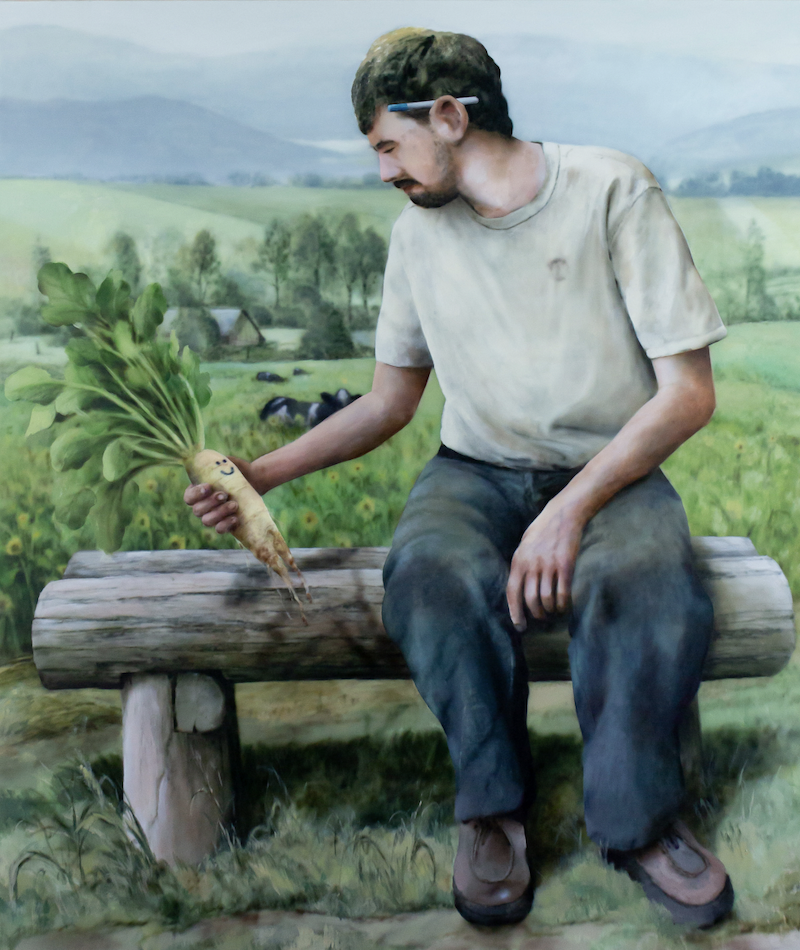

"Radish My Friend” features a farmer holding an oilseed radish. This is a very important crop used in regenerative agriculture, especially for green manure, due to its strong rooting and soil-improving properties. It roots deeply, improves soil structure, and serves as food for the entire microbiome. Yet, in his village, it is a very unusual crop. That’s exactly why people look at it with skepticism.

In the painting titled “In the Yard”, a farmer is shown in the courtyard counting money. In the context of sustainable agriculture, this is a great paradox of farming —more of an idyllic composition of so-called idleness. The poverty of the yard is symbolized by pigeons pecking at the very last grains of wheat. If Courbet’s Realism paved the way for challenging convention by depicting everyday life on a grand scale, Social Realism aimed to highlight the declining conditions of the poor and working classes, challenging the governmental and social systems responsible during the World Wars. Both movements responded to the social and political tension of their time.

As Evan Pricco aptly noted: “Kačmarek’s work echoes the essence of Diego Rivera, Andrew Wyeth, Jacob Lawrence, Edward Hopper, Grant Wood, José Clemente Orozco, and even Dorothea Lange - not in style, but in essence and subjectivity.

On the surface, one might see echoes of van Gogh’s ‘The Potato Eaters,’ yet Kačmarek operates through a different prism. He integrates the legacy of socialism, labor, and 21st-century technological advances reflecting on the displacement of workers.”

In his practice the sustainability of soil emerges as a central concern, responding to the ongoing climate change crisis, which urges for new politics of regulation. This approach is especially relevant against the backdrop of recent agricultural strikes in Europe, which highlight the practical difficulties and discontent within the farming community. Rising production costs, foreign competition, falling incomes, and environmental constraints are at the root of this frustration. Environmental issues are at the center of heated debates today as we rush to find solutions to sustain our globalized and fast-paced consumerist society, which often fails to reach consensus. During ongoing global conflicts and political polarization, Kačmarek’s paintings resonate as a commentary on the challenges we face today, shaped by his first-hand experience and deep emotional attachment with the land.

Kačmarek’s paintings push us to consider the stakes of our current path and the possibility of a sustainable future. He not only shares his personal journey but also invites us to reflect on broader societal issues - from the environmental impact of traditional farming to the cultural resistance to change. His work is a reminder of the contemporary need to concile the wisdom of the past with the demands of the future, encouraging a deeper connection to the land and each other.