George Condo

The Artificial Realist

Interview by Charles Moore // Portrait by Andrea Rossetti

In the comfort of his bedroom, New Hampshire-born artist George Condo contemplated his place and personal perspective on art criticism and history. Typing away on his laptop, he expressed how tired he had grown of critics comparing his work to Picasso’s, underscoring that he hoped to deconstruct misconceptions about his paintings by writing about the process himself. Condo wants viewers to know that he has his own viewpoint on art history. The artist posits that art bears no chronology; something created 30,000 years ago in a cave might look contemporary, while a modern artist could easily reconstruct a Renaissance painting. There is no linearity to art, Condo explains.

As a painter, Condo sheds light on the minds of imaginary characters, downloading their subconscious via the imagination and crafting subjects in the manner of a novelist or playwright. Calling his humanoid figures “abstractions of characters,” the artist depicts imaginary beings who reflect the sociological pressures and internal selves of fictionalized people. It is important to note that, though his compositions present as human-like portraits, Condo’s subjects do not actually resemble traditional mortal beings. Rather, his individuals are mired in either absolute nervous breakdowns, moments of pure joy, or perhaps a combination of the two, emotional states entirely fractured, yet pulled together by nightfall.

While the subjects may look the same to people on the outside, their inner worlds are entirely self-possessed. Or, in Condo’s words, what’s happening in their heart and soul are entirely oppositional. Readers might see “The Smiling Sea Captain” (2006) as an illustrative example. The large-scale oil painting reveals what Condo calls the metaphysical construction of a human, the subject like a construction site: built from multiple parts, with a crazed, clownish look in his eyes—smiling. In the meantime, a spear plunges through a literal target on his chest, complete with a descending downward like a play on the notion of “dangling a carrot.” The composition is eerie, yet the viewer can’t look away. The artist references the work as inspired by John Lennon’s song “Working Class Hero,” where the lyrics wryly wonder at the incongruity of “The Smiling Sea Captain” continuing to grin during his execution.

What is the meaning of this? Condo states that perhaps the overarching lesson is that a state of happiness overrides a life of fame or popularity. A man working at Home Depot, he maintains, may well be more fulfilled than someone toiling in the pressure cooker of the art or music industry. Despite his line of work, Condo finds the insatiable urge for success quite alien; simultaneously, he believes the hordes of young people giving voice to so-called “self-empowerment” without enduring the labor of factory work, for example, creates further dissonance. The artist explores these concepts by focusing on garbage collectors, school bus drivers, and teachers as he creates his subjects. On the rare occasions he portrays a celebrity or supermodel, Condo puts his own spin on the profession, albeit crazily and horrific, yet designed to incite smiles of delight—because his protagonists are smiling too.

Given Condo’s background in music theory, it’s no surprise that his work plays melodically. Painting in a manner that incorporates rhythm and tempo, he works quickly to catch all the notes when necessary, slowing down when his subjects exhibit patience. Replacing key signatures—sharps and flats—with colors, he improvises like a jazz musician. The process is remarkably intuitive, as he summons his innate musicality. His sculpture “Constellation of Voices” (2019-2020) is carefully placed outside of the Metropolitan Opera—a shining beacon of light, a voice for the people, but also an homage to the form and its roots in the human voice. “Constellation II” is a smaller, slightly altered version of the work, a golden fusion of human and alien parts, named in the same fashion as the Apollo space missions.

Some parting words from the artist reflect how, at this point, the entire world is manmade, a fact that Condo honors by delving deep into the writings of existentialist philosophers like Heidegger, Nietzsche, and the pre-Socratic Anaximander, who states how “that which rises gives rise to its falling.” Condo is firm in his belief that what goes up must come down, and so he strives to move in every direction. The concept he hopes to manifest in his paintings is conversational in nature, an artist intent on showing the figures in his works engaged in conversation with one another. These subjects are guided by a collective subconscious that mystifies the viewer and consequently, what makes them so striking.

Charles Moore: So your show Humanoids in Monaco is pretty exciting. Tell me more about the humanoids.

George Condo: To be honest, I was tired of people talking about Picasso and all these influences and guiding principles in my work. These kinds of misconceptions about my work could easily be deconstructed if I were to write about it myself. So the thought came to me, “Why not just do a book once and for all, where you hear what the artist has to say about their own work?” It's great to read an art historian's perspective on things, but my perspective on art history is so different from that of your normal academic art historians.

Let’s talk more about that—your perspective on art history.

Well, my perspective on it is that there is no real meaningful linearity or chronology when it comes to art. What I mean is something that could have been created 30,000 years ago in a cave in Altamira could look more contemporary than something you might see tomorrow in a gallery. That embodies the idea that an artist should have the freedom to embrace any language or any cultural influence that he might find in the world into his own art. As a painter, you should have the freedom to decide that you want to paint in the same style as something painted during the Renaissance—even if the subject matter changed. Or you might want to paint in the style of the 1940s if the subject matter is relevant to today's world. You could include five or ten languages from different periods of art simultaneously in your own paintings. And why not—who said you can't?

What are the similarities and differences between a humanoid and an imaginary person?

Well, an imaginary person can be something that comes from your imagination, like a character invented by a novelist or playwright. Humanoids are imaginary persons, but they are the result of societal pressure.

But the humanoids are a bit different, aren’t they? What would you call these figures with their opaque blue eyes and long necks and faces? And what would you call the figures that someone like Picasso painted? They're basically human-like figures.

In those cases, they were abstracted to a degree that would fit that artist's “stylistic development.” These paintings of humanoids are about what's going through the human mind and the pressures they have been subjected to, which have created these “fractional” or “peripheral” kinds of beings, so to speak. They are human-like in the sense that they are portraits, but they are in the moment of either a complete nervous breakdown or one of joy and happiness. It could be both at the same time, all in a single day… There could be a disastrous situation that takes place in the morning where their emotional state is completely fractured, then by the evening they've pulled themselves together and they feel like themselves again. But to everybody on the outside, they look the same. But what's going on in their mind and what's happening in their heart and soul is totally different.

Speaking of what's happening in between a person's heart and soul, let’s look at The Smiling Sea Captain. What's happening between his heart and soul?

Does he have one? That's the first question. The Smiling Sea Captain is essentially a kind of metaphysical construct of a human. He's built out of multiple parts, and he's got this crazed look that looks back at you. You walk into the room, and he is kind of looking over at you with a big smile on his face. In the meantime, he's got a harpoon through a target on his chest. Then there’s a carrot hanging down—that luring carrot, the carrot that's put out in front of us that we're always reaching for to get further ahead, whatever the cost. I just remember this one lyric of John Lennon’s in that song, “Working Class Hero,” which goes, “There's room at the top they are telling you still / But first you must learn how to smile as you kill / If you want to be like the folks on the hill…”

I think that The Smiling Sea Captain is probably the guy who learned how to smile even as he is killed until he finally got it. And then, when he was harpooned, he was still smiling.

John, the real genius of The Beatles. I always say all the greatest songs by the Beatles were written by John.

Yeah, I think so, too. There’s another song that he wrote after he'd broken away from The Beatles, and shortly before he was murdered. It’s called “Isolation,” which was all about people saying, “People say we've got it made / Don't they know we're so afraid / Isolation / We're afraid to be alone / Everybody's got to get a home / Isolation…”

I think the idea of this popularity thing really struck him. This comes out in “Working Class Hero”—life is not all about fame and popularity; it's about happiness. It's like this guy who's working at Home Depot who's got a wife, three kids, and maybe some grandchildren. They have their Easter Sundays together. They have a nice life. They don't live under this kind of competitive pressure of the music or the arts or anything.

They're not under that kind of pressure—and there's something to say for that! And so, generally speaking, a lot of the characters that I paint are the garbage collector, the school bus driver, the schoolteacher. They're never really under that imposed kind of pressure to achieve.

There’s one painting I did in this show called The Supermodel. It was done in 1999, during the era when everybody was looking at Victoria's Secret, that whole reign of the supermodels. So many women were glamor-struck by them, but also intimidated by the idea that “Geez, I'll never be a supermodel!” So, my version of a supermodel is probably one of the most insane, horrific personalities, something like the constructed figures in the exhibition. But, nonetheless, it puts a big smile on your face.

Why the big smile?

Basically, you smile back because she's smiling. As you walk into the room, it’s the first painting you see in the room of female figures. Immediately it’s the kind of art that makes you smile. You smile, even if it were a painting of a crucifixion because that painting is painted so incredibly well—I’m thinking here of a Velasquez—although the subject matter is obviously pain, sorrow, horror, and death. But if it's painted so beautifully, no matter what it is, I always find that it puts a smile on my face. It’s the same when I hear somebody playing music. I think, “My God, I can't believe that guy just played through those chord changes the way he did!” I like that effect in art.

It can happen with a Mondrian. You look at a Mondrian and you just gasp. You don't know what it is, but it just puts things into that contemporary frame. You look at a Barnett Newman painting and just think, “Wow!” Pure elimination of anything other than space, fractured space! And his concept of how to make a beautiful painting is just amazing.

It seems to me that a lot of your work critiques Western culture. What other areas of the culture do you feel compelled to examine?

What I find fascinating about Western culture is the insatiable urge for success or the good life. This kind of strange self-empowered drive is what I see happening in the younger generations who haven’t really gone through the motions of, say, working in a factory like I did. And I don't mean Andy Warhol's factory. I mean a real one, making plastic cups, working in air cooler factories. And getting to that point where I would say, “Listen, if I don't get my act together and make it as a painter, I'm going to be working in this place for the rest of my life!”

The theme of Western culture—let's just call it US Western culture—is to glorify the idea of self-empowerment without really understanding the things that we’ve done wrong in the past and are still doing wrong. Nowadays, the word “accountability” has become a catchphrase instead of something that happens. This is what I see as a problem: when you think that all you need is a catchphrase. If you see accountability taking place, maybe the term would be justified. But that leaves a lot of areas of Western culture that require accountability open to question. What I am referring to is the negation of various kinds of artistic forms and artistic cultures that have existed in the world and wanting to keep this sort of Western concept of democracy alive. What would you call it? You'd call it a sort of “Congress of Academics” emanating from some part of Washington.

Do you mean like the French Academy in the past that dominated art?

Not, exactly. There seems to be a kind of universal congress out there that defines and decides what's right and what's wrong with people's art, with people's music, with people's everything. But, when you come down to it, it's the audience that listens and decides. And it's not just art. It could be a symphony orchestra where somebody will audition to be a first violinist, or an oboe player or a flute player. And there's a group of judges that have had these chairs for years, and they'll decide about who could be in an orchestra that will play around the world. It's almost like a courtroom of judges. Now, if those judges were a diverse group of judges, that would be a more objective way of determining the quality of what they're looking at or listening to.

But if you've got 12 old fuddy duddys from wherever in the world determining who gets what, you realize they're really biased. We’re probably not getting the best talent. That's the way it's been in the art world and the music world. I can remember back in the ’80s, with a close friend of mine, Jean-Michel Basquiat, when no matter how far he got, no matter how great he was, in his private moments with me he’d share the feeling of being used. I remember I was in a bar having a drink when he came in and I said, “How are you doing, Jean?” He says, “I'm all washed up in this town.” I said, “What do you mean?” It was like a line out of a 1940s film—like On The Waterfront or something.

Yeah, Paul Newman walking in with his 5 o'clock shadow.

Yeah, completely. And so we had a drink together, and I said, “Come on man, you're one of the most famous artists in the world. What are you talking about?” And so then we went out for a walk. We did a big circle and came back around and just walked it out of his system, how he felt the pressure of being a “token black artist,” that type of thing, to use his words. Even though David Hammons was working, as was Jack Whitten, and all these other guys, he was the one with recognition—and he was literally out of work, nothing left. He had a guilt trip for that, almost like a soldier in the field who feels like “All my men died, but why am I still here?” That was an introduction for me to the reality of the social pressure that even the greatest artists feel.

I can quite appreciate your point. So how do you answer people who ask, “What do you call your art?”

I guess I would call it “artificial realism.” To me, artificial realism is a realistic representation of life as it is. It’s the subject I'm representing that is artificial, where you could define “artificial” as man-made. So, to me the present world is man-made. What's happening to people is man-made. And I am defining realism as that which is external to us, independent of our perception. We can't see it but it's really there. So then I went and thought about this artificial realism phenomenon, and turned it into a reality. It was almost as if an equation I had created became the world we live in today. All that world of disinformation, the fake world news, the Facebook posts, all those people designated as friends who are not your friends, all that information coming from cyberspace into our everyday lives—that’s our reality today. Truth is, we can't be sure what any of it is, but all I see is that artificial realism is the world we inhabit today. It's not related to art anymore. I think when Einstein conceived E=MC2, he never thought that it was going to turn into an atomic bomb.

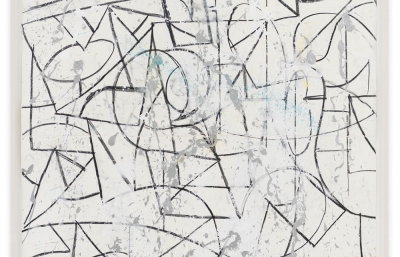

WINTER 2024 Cover art by George Condo

Little Henry, Acrylic, oil, and pigment stick on linen, 78” x 82”, 2019.

© 2023 George Condo / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Listening to you speak about these things and absorbing your text in the catalog for this show made me wonder what you’re reading that informs you. Initially, I thought of some of the great philosophers since you reference Aristotle, but then it dawned on me looking at the work, that it has to be existentialist.

Yeah, I'm very much into the existentialist view of reality. Think of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. But before that, I came across this one book by Heidegger on early Greek thinking that really influenced me. He was citing a particular from this pre-Socratic philosopher, Anaximander of Miletus, called the Anaximander Fragment because all that is left of his writings is this fragment. So profound, it's been analyzed by Heraclitus, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Plato—all of them—because it's one of the first fragments ever seen in Western thought. It says, “They pay penalty and retribution to each other for their injustice in accordance with the ordering of time.” The underlying idea is something like this: that which rises gives rise to its falling and with due recompense.

In the simplest of terms, what goes up, must come down. But it's really got a lot more meaning than that. I think the philosophers were trying to determine the notion of being. They started with “What is being?” and “What is the being?” Then it went to “What is the being of the self?” and “What is the appearance of being?” And that generated more questions: “Is it the appearance of being?” or “Is it the being of the self?”, making all these determinations and distinctions. This is where Hegel comes in. To me, the concept of the “being of the self” gives rise to infinite possibilities of what the self—that is, we ourselves or the self in general—could possibly be. This is the thing Hegel speaks of with his concepts of “Bad Infinity” and “True Infinity.”

To define a thing, Aristotle put it very simply by saying, “A thing is everything that it's not.” So how do you name things? Simply—things are everything they’re not. And so, when I thought about all these philosophical ideas on existentialism, it all boils down to the absence of existence. I remember reading about somebody describing existentialism to a layman: “Picture yourself late for an appointment. You walk into that café, you scan every face, and you say, “No, that's not him, that’s not him!” And then you realize that the person you’re meeting is not there yet. But you see the absence of his being in every single face that you scan until you come to this conclusion: ‘Oh, I've just been involved with the idea of the absence of being.’”

So I believe that the writers that came out of that era, including Félix Guattari—who I met in Paris back in ’85—had gone through that whole existentialist experience and wanted to anticipate the next philosophical development in humankind. Guattari co-authored A Thousand Plateaus, which is a study of schizophrenia. In the last book he co-authored, Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Guattari touches on the idea that schizophrenia has always been prevalent—strangely enough, that's what Didier Ottinger called it in his essay Schizo Frenzy.

It’s like one of the first paintings that I ever exhibited in 1984. It was a white canvas with the globe, which had America, South America, and Canada on one side, and Europe and Africa on the other. It was like the two sides of the globe were turning in two different directions. I called the painting “The Great Schizoid” because I felt as if there was a symbiosis between an idea in one hemisphere of the brain and its counterpoint in the other hemisphere. The globes were the two O’s in the name “CONDO.”

I think that if we were to tap into the deepest part of our subconscious, we would see that there's another existence of our own self living within our subconscious. It has been Dropboxed into our brain through our upbringing, through our early life, and it's filtered into our subconscious mind. The subconscious is seeing what you're doing today, seeing what we're talking about and what's happening around us, and then relating and transmitting messages to our conscious mind. I thought to myself, I'd like to try to paint a figure that is guided to a certain degree by the subconscious. But we can't necessarily tap into it. I thought, well if I create a human-like being, I can also have the power to go into his subconscious and create what his subconscious looks like on the outside rather than the conscious person.

I could take that subconscious energy—all that hardwiring, all that uploading that happens from when you're a child and how you are brought up and how it informs you throughout all your life. By creating an imaginary being, I have access to a self—and it's subconscious—because I'm putting it there myself, and I'm going to be the one that downloads that figure onto the canvas. I could describe it as “psychological cubism”—that is, you're seeing four sides of a personality simultaneously, only now you're viewing all that from the outside.

Is there anything else about this exhibition you'd like to tell me that I haven't asked?

Well, we’ve covered the exhibition. Another thing in Monaco is the casinos. I was playing a lot on the roulette wheel and thinking about Francis Bacon being down in Monaco and playing at the casino. The rule of the wheel is when it is in motion, you put your chips down on a number (or block of numbers). To me, that’s like throwing paint at a canvas. Either you hit the spot, or you don't; it's like life or death every second that the wheel spins. Every time you put 500 bucks on 10, or you put it on 29, if your number comes up, you're a winner. As a painter, I could see why Bacon spent a lot of time down at the casino and I could see where, as a painter, that kind of chance is always happening in art. You never know when you get to a blank canvas what you're going to do until you start doing it. And so the show is all about chance as well as intentionality.

It's about the chance of walking into the room and thinking, “I wish I could register what somebody is superimposing their perception on each painting would be.” I wish there was a kind of a meter that would tell you, like a blood pressure meter. I wish I could take the mind pressure of the audience so I could say that I think the show really defined the concept of the humanoids that I wanted to get across—not only with the paintings but with the rooms themselves because when we organized the works, there were actual conversations going on between those paintings.

George Condo’s Humanoids was on view at the Villa Paloma in Monaco through the Fall of 2023. This interview was originally published in our WINTER 2024 Quarterly: Buy it here.