street art in the granite city

Nuart comes to aberdeen

Text by Evan Pricco // Photography by Ian Cox

There is a cemetery that lies in the middle of Aberdeen, Scotland's city center that, upon first blush, resembles many of the great gravestone treats of the UK. With dates stretching back to the 18th Century, most stones are illegible from years of weathering. But there is one, still clearly readable and unusually “kempt” gravestone. Here lies the tomb of John Henry Anderson, the “Wizard of the North,” a famous Scottish magician. But why is the tomb so clean? Well, of course, Harry Houdini, who called Anderson his inspiration, arranged for the gravesite’s upkeep while Houdini himself was still alive. It’s these little stories, and that the cemetery now provides a wonderful vantage point of a massive Herakut mural on Aberdeen Market that make Nuart’s newest festival in the northern Scottish coastal town, so special.

Like many cities around the world who have seen their downtowns transform in recent years as more and more young professionals move in, where property ownership has moved from locals to international conglomerates and offshore accounts, Aberdeen is no different. It is an oil city that is feeling the economic rollercoaster of the industry. Unlike many other European cities, It is also in the unique position of not carrying decades and decades of street art history. It’s the Granite City, grey by nature, not un-beautiful but not close to bright either. When the Stavanger, Norway based Nuart Festival was commissioned to bring their now famed version of the street art festival to Aberdeen, a unique festival in that it draws artists and academics alike, connecting threads of art history into street art’s significance, Nuart had a blank slate of sorts. And this is where Nuart Aberdeen thrived.

I asked Martyn Reed, Nuart’s founder about moving the festival to another city, with the challenges of measuring success and community participation, and he gave Juxtapoz a particular detailed answer.

“Good question, I think it was John Lydon who said, ‘If you’re pissing people off, you know you’re doing something right’,” Reed said, which if that’s the case, then Nuart Aberdeen is a dismal failure, because it’s smiles all around. We discussed very early on what would Aberdeen regard as a success, but we also discussed, what would be a success from a volunteer’s perspective, and an artist’s viewpoint. Are we engaged in process, what does a local trader want beyond increased footfall, how can we engage, include and activate local artists? Does a 9-year-old demand something different from a pensioner? Are the caterers fulfilled, are visiting journalists getting access? All of these elements have to not only ‘work’ but also give purpose. What I find really fulfilling is seeing all of these people and elements, having real purpose. Feeling purposeful if you like. There’s a lot of power and energy in that. I realized on this production that everyone's purpose didn’t have to match. It isn’t just about creating great and interesting public art, and maybe a volunteer didn’t actually like street art, maybe they just wanted to meet new people, work with kids or work collectively, and as long as their purpose isn’t in conflict with anyone else’s, then that’s success. Companies and city councils spend months and years and millions on analyzing the ‘outcomes’, the ‘deliverables’, the ‘datasets,’ particularly now that ‘Smart Cities’ are all the rage, but at the end of the day, you just have to find the right people, and trust each other. I think we put together quite a formidable team, forged some really strong connections, made friends for life and created some incredible public artworks. All without pissing anyone off. I’d call that success.”

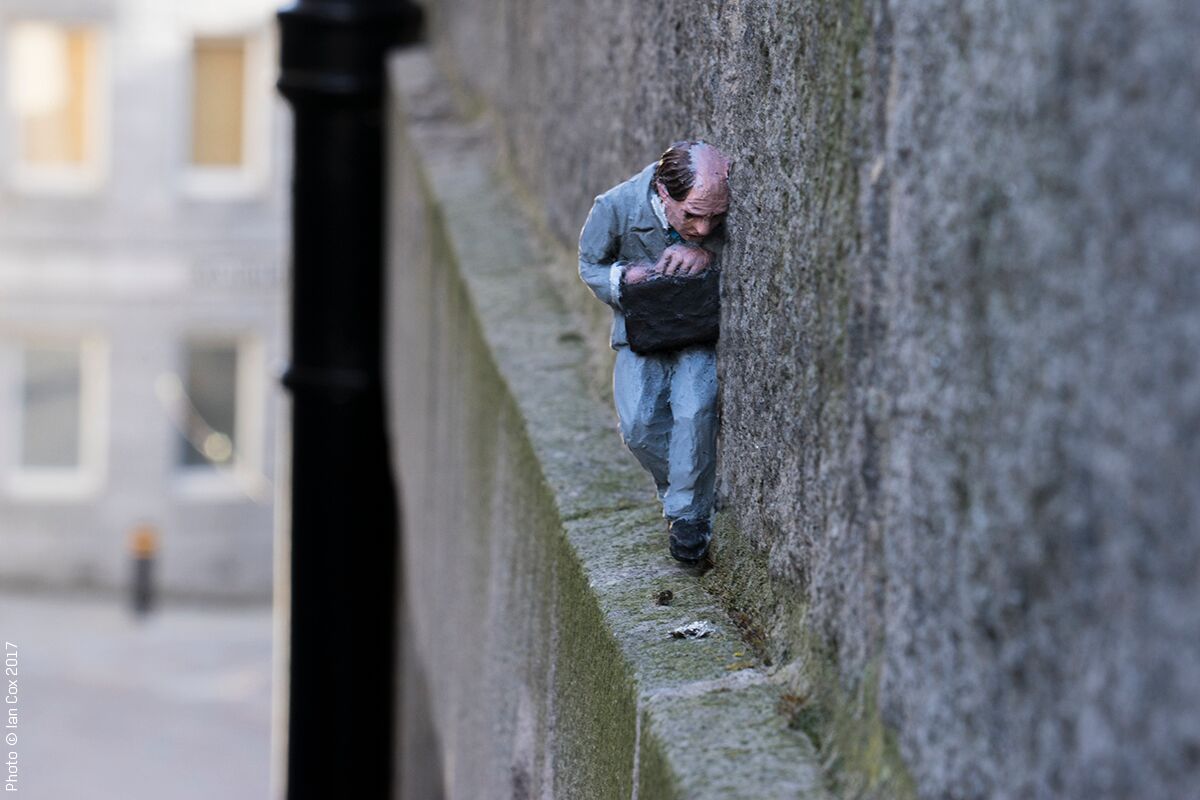

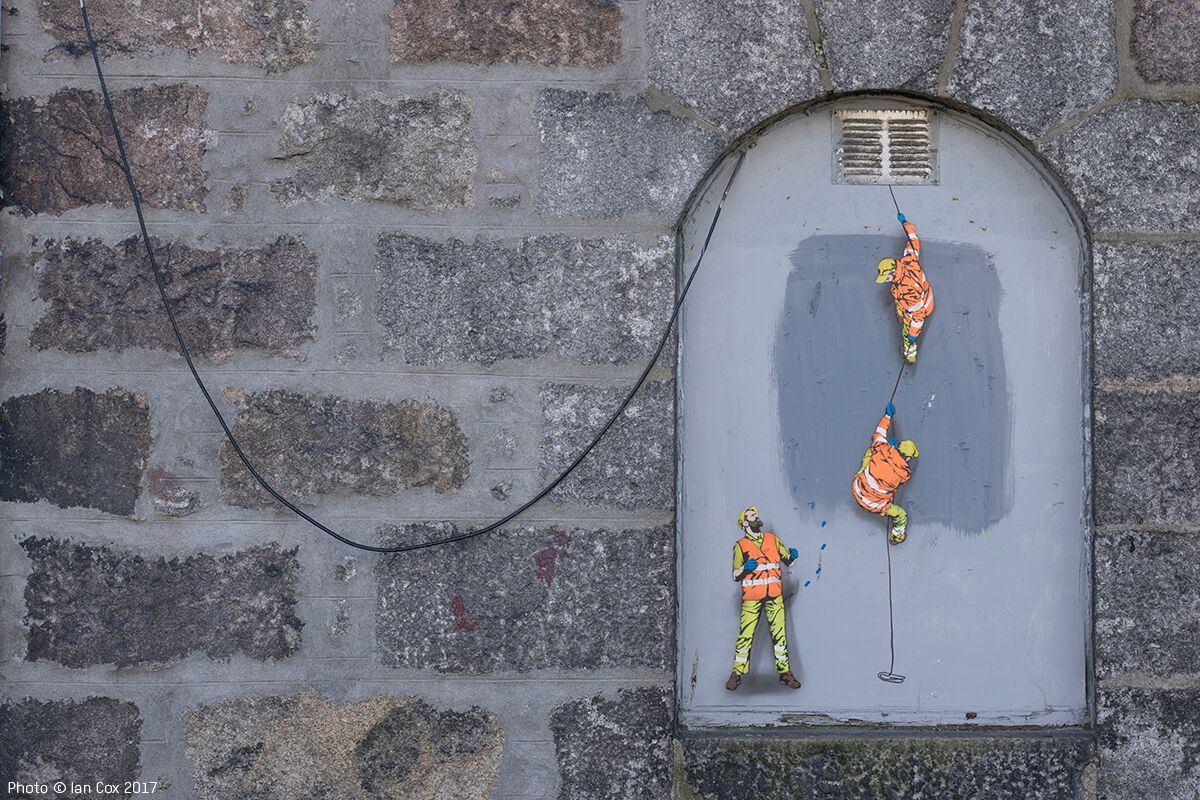

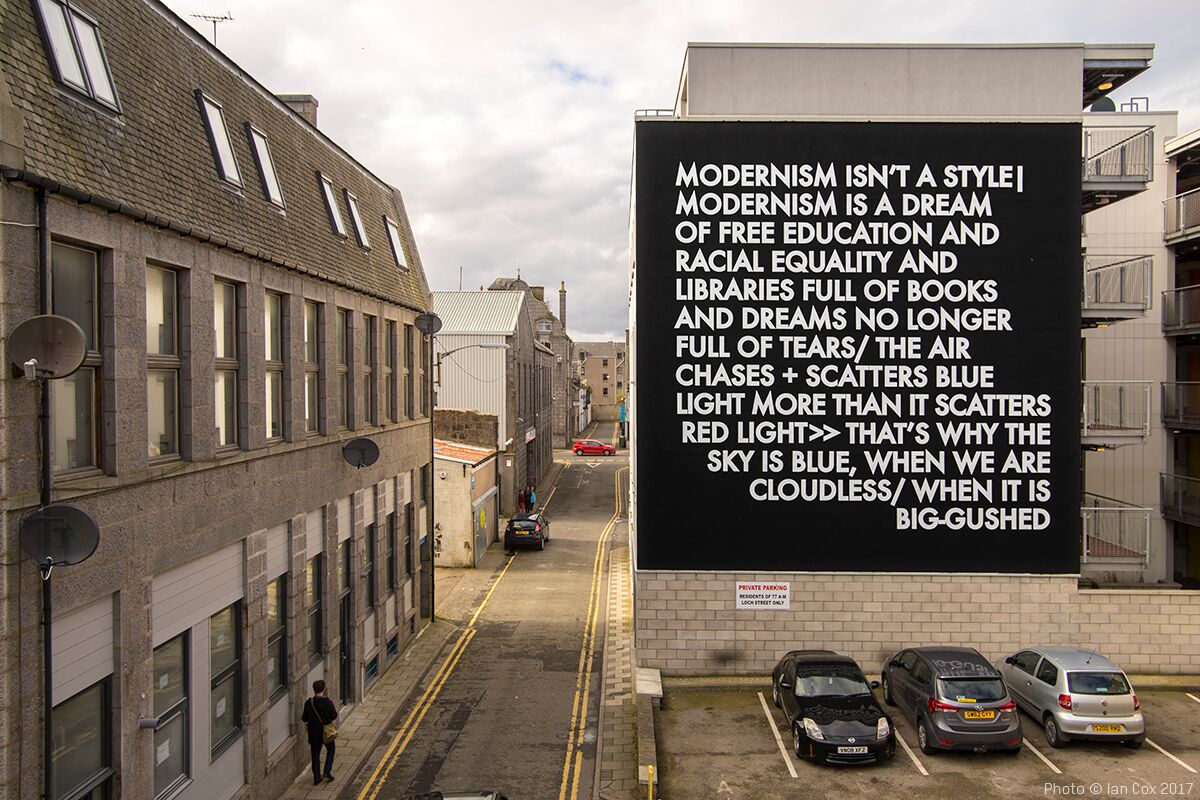

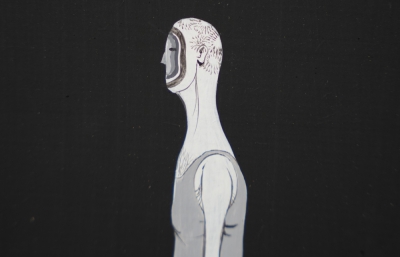

For a city made of granite, full of Gothic and Brutalist architecture, and a gigantic William Wallace statue in the middle of town, Nuart’s curation of small street art interventions and murals is both a fascinating and unique marriage. According to our city guide for the week, Aberdeen native and artist/curator, Jon Reid, who runs the local arts blog, Moods of Collapse, gave us insight on past art activations in the city, including Painted Doors and Release the Pressure, projects that have begun to breathe creative life into the oil city. But Nuart’s experience in combining public art with academia, it’s history of contextualizing Street Art into the lineage of Dada or the Situationists, emphasizing the politics of interventionists practices, provides a climate for the public to engage in art in ways rare in the contemporary art world. Multi-storied mural works by Herakut, Add Fuel, M-City, Fintan Magee, Julien de Casabianca, Robert Montgomery and Martin Whatson, and smaller, almost playful works by Jaune, Alice Pasquini, Isaac Cordal, and Nipper brought the city to life for locals, but also refocused the attention on what the city of Aberdeen already has: a wonderful city museum, a legendary printmaking studio and these recent street art projects. Nuart acted as both a reminder and completely original experience for Aberdeen, one that could revitalize the local scene while hosting internationally famous muralism.

Multi-storied mural works by Herakut, Add Fuel, M-City, Fintan Magee, Julien de Casabianca, Robert Montgomery and Martin Whatson, and smaller, almost playful works by Jaune, Alice Pasquini, Isaac Cordal, and Nipper brought the city to life for locals, but also refocused the attention on what the city of Aberdeen already has.

“Having read about Nuart and visited the festival in 2014, I had a fair idea of what a huge deal it was to be coming to Aberdeen,” Reid told us. “But I feared people would be against these strange paintings suddenly appearing on their walls, at least until they saw them finished! But I was pleasantly surprised, almost off the bat people were interested, intrigued and ready to engage and it hasn't stopped. I think when people realize that these artworks are permanent, or as permanent as any street works can be then the positive feeling will just keep going. More often than not it's the same old faces who support and engage with these events, but Aberdeen has shown a bigger appetite for them since the painted doors project and Release the Pressure but the reaction to Nuart has been unlike anything I've seen before. This feels like a step change for Aberdeen as a city and I think it’s done more than just beautify a few walls, it goes much deeper.”

While leaving Aberdeen this week, urban researcher and a common face at Nuart’s academic conferences, Pedro Soares Neves, and I were discussing the keys to Nuart’s success as both a festival and dedicated nurturer to the scene’s historic importance. Much of that success lies in the festival’s dialogue and openness to be self-aware and critical. Nuart’s founder Martyn Reed is constantly exploring the idea of a “festival” within the origins of classic interventionism, the awareness that street art’s ascension to becoming the most popular art form in the world, does not go unnoticed. The festival is both a platform to look back on what came before, but also explore what is utterly unique about street art culture in 2017. The traditional Nuart kick-off event is the now infamous “Fight Club” night, where members of the academic world, journalists and artists debate subtle differing genres of street art and it’s history. These events relieve the pressure of taking the movement too seriously while also taking into account just how massively successful street art has become into transforming how people interact and view art. This, is unavoidable, even if the art criticism wants to avoid the subject all together.

There is no denying the massive crowds taking in the opening Street Art tour on an early Saturday morning, with hundreds of people following both Brooklyn Street Art’s Jaime Rojo and Steven Harrington, as well Reid, around the city centre to see the new additions to both back alleyways and familiar building facades. There was genuine excitement in the stunning and subtle mural by Portuguese-painter Add Fuel taking Aberdeen’s hometown tile patterns found in both business and residential entryways and transforming it into a literal-center-stage-point-of-pride of Belmont Street. Or M-City’s commentary on the diminishing oil industry, Fintan Magee’s nod to the coastline and Alice Pasquini and Jaune’s creating trails of stencil works on city blocks that one had walked on hundreds of times but failed to look around with much interest. This why the crowds came out; it reinvents a city in ways that even the organizers or city council can’t quite predict until there is true interaction with the work.

"I think it was John Lydon who said ‘If you’re pissing people off, you know you’re doing something right’..."—Martyn Reed, founder of Nuart

Thinking of this idea, I sought out John “Nipper” Cunningham, an artist living outside of Bergen, Norway whose street art interventions as Mission Directives rely on this public interaction. Or as Nuart so smartly describes, “focuses on social ideals of sharing, creativity and citizen-led communication in public space. By questioning who has the power and authority to communicate messages and create meaning in our shared spaces, his work becomes part of a broader conversation of social significance.” In a sense, his work is the embodiment of the festival, the idea of fighting power structures through alternative means of communication and commercial subversion. For Nuart Aberdeen, Nipper placed interactive works around the city, requiring the public to follow instructions or make their own creative choices if they were lucky enough to notice the work. And what I wanted to know from Nipper was how these interactions played out on both unsuspecting and searching passerby’s.

“To an extent yes I was surprised by the interaction,” Nipper says.” Often it feels people, even when given permission, see art as something 'not for them' or only for those that work in what appears a close domain and for the few. On this occasion it seem they were released of that hesitation. What is perhaps interesting with small interventionist work is they can have an intimacy that says ‘It is not beyond you.’ It can meet you where you are. That the natural creativity we each have, can finds a voice and passage. There was an embrace.”

Nuart has long been one of the most forward-thinking, relevant and thoughtful street art festivals in the world, and they paid Aberdeen a proper respect. And as Reed told me, which I think was the sentiment I felt leaving Aberdeen this year, is simple: “Our stated mission is pretty simple, it aims to make art part of everyday life, to free it from established hierarchies, or at the very least, loosen the grip a little, and to show the guardians and gatekeepers of contemporary art, that there is a vast untapped audience for visual culture.”