Vision Walk: ComplexCon

With Daniel Arnold

We recently partnered with Vans on a specially curated group of photo walks at ComplexCon with photographers RAY BARBEE, Daniel Arnold, MIRANDA BARNES, and BROCK FETCH. Each photographer brought their own unique styles and backgrounds to the walks, leading a group around the convention and City of Long Beach.

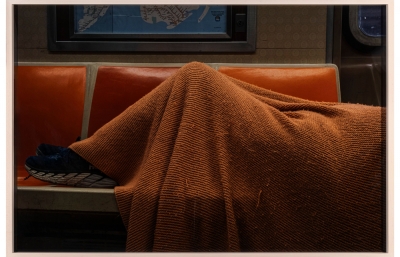

“How could we possibly get anything good out of what we are given?” Daniel Arnold proposed to everyone before setting out on a photo walk around downtown Long Beach. “How can we not be afraid? How can we do what we need to do to get the pictures we want? If you don’t think about pictures and you just think about that you’ve been given access to this weird new video game level, that you only have for a short time, that you need to take advantage of while you can, and pay attention to how you feel, and pay attention to what’s funny, and pay attention to what’s weird, and what you don't find in your regular life, that, if nothing else, you’re going to have proof of this weird time that we had together that we’ll never have again.” The New York City streets are Daniel Arnold’s life-long photo school, his boot camp and his continuing education. It’s not so much about the pictures he continually reminds us, but the process. “...school is just free outside your door if you have the patience and the time to put into it… It’s just a place to learn how to be in the world. It’s not about the street.” After his Vans Vision Walk at ComplexCon earlier this November, we sat down with Arnold for a conversation about that process.

Alex Nicholson: What the first images that you remember having an impact on you, that you remember understanding as having been made by someone?

Daniel Arnold: It's funny, you wouldn't think this maybe, because I'm so voraciously a photographer, but I don’t think my photo instinct came that much from photography. Well, first of all, I just wanted to keep things.

Like collecting things?

Actually, I thought about it being at ComplexCon, but all the sports cards, just anything you would collect. I don't know what that kid instinct is, I think it's a little boy instinct specifically. I just wanted all of everything. And then I got older and it became about music. I worked at a record store where you could just have whatever you wanted. I voraciously collected music. I think it's just that teenage instinct, to put all of your energy into stocking the shelves of your life and defining yourself by what you consume. I think that it was sort of like this uncommonly pure thread that ran through that weird capitalist instinct. That there was something about the transitive, weird fleeting parts of just being myself that I wanted to collect too.

I do remember, and this has no bearing on my current practice or idea of what's right, but I remember being really photographically inspired by Wes Anderson movies. I was probably 17 or 18 and worked at a summer camp. They had this digital camera in the office desk drawer that was for their daily newsletter, because it was a sleep-away camp, so the parents wanted some proof that their kids were alive and happy. When I had a free hour I would go steal that camera and go around and take a bunch of weird pictures.

What made them weird?

Weird, like not the kind of stuff you normally would take, not summer camp fun-time action pictures but weird cinematic... like what I do now kind of, but in a way that was more Wes Anderson-inspired, I guess.

Of people?

Of people. I do remember these sort of wide layouts, with the kid up close on the right with space and signage on the left, very Wes Anderson-y kind of stuff. I guess I never thought of it, I never said it out loud, but I think that was an instructive first step of being more calculated about a picture, what an image is, what a camera does. And then right after that summer, I moved to New York. Falling in love with New York, whether you mean to or not, gives you so much visual context. New York is so documented, all the movies, all the pictures, it's just what America looks like in its own way of presenting itself. So, without even knowing what the photo history of New York was, I started reaching for that timelessness, that classic emotive, evocative, New York thing. I mean really so much of it is about New York. I try to be complete in an interview and talk about the times of being a photographer before I moved to New York, but it didn't really get any legs until I looked at New York and thought, "This is what I'm supposed to do with this city."

Watch a short clip from Daniel Arnold's Vision Walk and stay tuned for a longer video from a weekend of photo walks around Long Beach.

At what point did it start to become less about collecting moments of your life and more thinking about it as more of a photograph for other people to look at?

That's another one I don't really know. The truth is this has been extremely haphazard and mostly involuntary. I guess, without ever having thought about it really, I think that my reaction to Instagram, at least in the beginning, before it was so much a part of my story, was, I mean, it still is, to be a punk. The root impulse of my participation in Instagram is “fuck you.” It’s a smiling “fuck you,” but “fuck you.” A winking, “fuck you.” So, presented with this giant swath of population presenting their moments in a more or less common language, for me, that was like the dream canvas to piss on. It just makes it so easy to be a punk when everyone is doing the same thing. So, in that regard, I guess you could say that is how Instagram may have pushed me to be more complex... to go beyond capturing what was in front of me. I was never satisfied with just straight two-dimensional documentation. It was never quite photojournalism. It very often ended up being that, but that was the stuff that kind of fell to the side, and the ones that survived were the ones that were sort of undefinably spooky and pregnant and loaded and weird. Even shooting concert photos, I remember there was one night I shot this band Vietnam. I used to love seeing Vietnam. There was one night where I had messed up the switches and accidentally shot it in black and white. I went through photos and looking at them now, and they're mostly trash, but that night I felt something about the way those photos looked, tweaked my space in time. I felt like I had made a historical document, of a thing that nobody and no history will ever examine, but I look back at those and there was this weird extra dimension to them and that was always kind of my guide.

To take an unrequested step back, I also worked as a writer for ten years. I was a writer who was disgusted by my writing. I think I did a good job. I was proud of it to some extent, but it always came with at least some level of disgust. It was just a real breakthrough for me to start inching toward a place where I could tell a story without opening my stupid mouth. And I didn't set out to get there, but I started looking at photos, especially when I switched over to shooting film, where it felt like there was a real narrative happening there. Not a narrative photo even, just a simple, laid-out geometric that had something extra, some ghost to it. I started a website around that time, for nobody, in the vacuum, called "When to say nothing," with the idea that my first defining filter was: When is there a story that I can tell by saying nothing? That was a big meaningful first step for me, much more than anything visual. The visual, the technique, all that, is still coming. It was zero for a long time. It was always really emotionally guided and instinctive and more about stories than about pictures.

Is it weird for you now, that you were trying to get away from words and make it visual and now you're having to talk about your photographs and work?

It's not, well, to some extent I still make myself sick for sure, often. Pretty much every time. But I know that really going deep into photo brain has made me a better writer. It's just me a smarter curator of what's worth keeping, what's worth expressing, what is fluff, and what's extra baggage. The manifestation couldn't be more different between a photo and a paragraph, but it really is a pretty seamless continuation of that same impulse. Being a writer made me a better photographer, and being a photographer has made me a much better writer.

You talked about how long it took for you to develop the confidence to take the photos you wanted to take. How do you feel photography's changed you as a person?

I don't even know where to start. And not even in some corny way. It really is a very, very dramatic long distance between now and then. It's always hard to parse out what came from what. What's just growing up? What is the impact of moving to a big city? I can't separate it. My sense of myself is so, so, so, so different from what it… I've just come so far from that starting point and I think that a huge part of it was a giant breakthrough moment, it was being 33, having this ten-year writing career that wasn't the most, you know some blue ribbon greatly storied experience. But it worked, I paid rent for ten years in New York writing. When I announced that I wanted to do that, I got laughed out of the room. And it worked, and it worked quickly, but to be 33 and to feel this momentum coming, this really big momentum coming from a different direction and to make the choice to have the five minute conversation that it took to completely nuke every bit of progress I have ever made, was just a mind-blowing reconfiguration of what freedom is and what your life is. And I know it's very shallow and seems obvious, but just knowing first hand that you can have a five-minute conversation and be a different person, that is crazy volatile information to walk around with. It's insane. Because our instinct, of course, is to make our lives as small as we can. To make the world as manageable as possible, to make our own definition of ourselves and hide in it. Even if we don't feel like we're hiding, even if we're working our asses off, even if it's very meaningful. I'm doing it now, in a new way, but just to know that your hand is on the wheel of your life, was a crazy thing to find out, crazy, crazy thing to find out.

And then, for the next chapter to be this very broad elaboration on what was already a kind of seeking existence, to put all of my time and energy to just aimlessly wandering and looking at the world and having my personal thoughts all day long, and making the space just to be in the world, to honor my curiosity and put stock into experience and decide that the things that are supposed to be important are not important to me anymore, and I just need to occupy and experience my time, which is all there really is.

I don't know. It's corny, it's nothing mind-blowing, but to actually do that. To undertake that effort to take responsibility for your time and try to fill it and honor it, it does a crazy thing to the brain. It's like a religious experience. It connects me in some small way to the bigger picture of how humans deal with mortality, with time, blah blah blah. We find these little ritualistic purposes. Religion all of a sudden made sense to me, that there was this practice of irrational self-deprivation that led people to higher consciousness. And of course, it backfired and became a weird abstract disaster, but that original root of it makes perfect sense to me, having had this experience that there is a path in everyone's brain, which is the luckiest thing you could want to discover that leads to a richer experience of every day.

So day-to-day shooting, is it a religious experience, do you feel like you are on that path?

No, day to day, it's not even really there. It's just given the opportunity to pause and talk through justifying my existence, trying to articulate what the long-term effect of it is. There's lots of days I don't want to go. Any other one of those vices that serves that purpose. Like, if I fall in love? Forget it, I can't work. And that's a problem, I don't know what I'm gonna do about that. It's more like a long-range observation, it's just interesting to see what you do with your mind, given enough time to really think things out.

If you force yourself to go out and shoot when other things are bothering you are you able to move past it and get back into some sort of zone?

It's not that it bothers me, it just gets harder to access that, well, to totally contradict myself, that un-bothered state of mind. Yeah, it's harder to focus. It's harder to really immerse when you have something else that's really exciting to think about. But I don't think it lessens the reward if you still force yourself to go.

Does it affect the pictures you take?

Yeah, for sure. But it does not necessarily make them worse, it just changes it in a way that I could never do justice to in a description. There is such a hair trigger on that. The slightest change in breeze, or whatever happens to come on my headphones if I'm listening to music that day. The way that I think of it in the moment, is it changes the movie. And in a way, listening to music, or being in love, or being high or whatever, makes it easier to see life for the movie, but it also really impacts what the movie is. I like to aspire to hitting the movie where my brain is at its most involuntary, where I am exhausted and sort of outside myself and just in the rhythm of walking forward…

How does that transition to shooting professional projects?

As it applies to now being a professional photographer, where I get put in situations where I don't know what to do, I don't know how to manage. I sometimes don't have the access I am supposed to have. I sometimes am supposed to take the kind of picture that I don't really know how to take, and that fear factor has been really interesting to add to the equation, to see how being afraid very quickly dismantles me to that instinctual core. I don’t know what that is, it just breaks me down much quicker than I have been able to do on my own. And every time I feel like I've blown it and I've made shit. I get the photos back, and I'm like, yep, garbage. Then I spend some time, go through them, cut off the excess, and get to the more vital core of it, and I'm always amazed. Almost none of it is something that I've done intentionally. Obviously, I have to be this idea factory and know where to put things and think about what's going on in the background, but there's no anticipating or calculating the impact of a thing.

I don’t know, we got in very briefly to the film versus digital thing on the walk. And for me, that delay of revelation of impact, of purpose, it's the best part. You don't know, there's just so many layers of process. There's the crazy guy who goes out and sticks his neck out and takes the pictures, walks all day, exhausts himself, whatever it is that I'm doing, pretends that he knows how to be a fashion photographer on a beach in Greece or at the Republican National Convention... I really have been lucky to have such a wide scattershot of assignments. I feel like George Plimpton. Then there's like the lonely middle of the night guy who gets the first pass at the photos and is so disappointed. Then there's the later on, less affected, scientist brain that goes through and is like, “Oh, maybe there is something sort of developing here.” The impact really takes time to reveal itself. I am so hooked on that process, it’s just the most satisfying process in my life.

How about the other way around? How much does the place you're in effect your mood, and then cycle back into how you're shooting?

Good question to ask me in Los Angeles. There's something about in general, specifically my L.A. experience, which I so value and sometimes even crave. But my L.A. experience is that I come here and I feel like such a stranger, and I feel depressed, and I feel alienated from myself, and I feel powerless. I don't know how to socialize. Have you ever seen Superman 2, where he voluntarily loses his powers to relate to Lois Lane?

Yeah.

I think about that all the time. There's this scene where he goes to this redneck diner and gets his ass kicked. And that guy, that version of Superman, who gets his ass kicked by an old guy in a red flannel shirt, that is my archetype. I love to go to that place. It's very uncomfortable there, and it doesn't feel good. There's this whole stomach thing I associate with it. I also think of that mini-season of The Sopranos, where Tony is in a coma and he lives out that alternate reality where he doesn't really know his name. I love that space where you're stripped of all your powers and have to re-figure out what you are, and what you possibly have to contribute in this totally alienating and foreign landscape. So yeah, the landscape makes a huge difference. It takes me a while to have the confidence to even see properly.

I just did a thing the other night where I was on a movie set. It's a movie set that's run by my friends, but setting foot in that space for the first time, where all of the energy and action is going away from me. I have no power, all I can do is get in the way. And that feeling of embarrassed meekness is very hard to sweat through, but it's the best place to go if you can leave it at the end.

In hindsight, it’s the best feeling? Or during the moment?

In the moment it's terrible, in the moment it's so unpleasant. It's an absence of comfort. There's no safe place. And it’s definitely not the best feeling, but I think just the most valuable space to seek out, to go and come back from. To go and have that problem, I think is just a great use of your time and your mind.

And just to learn how to deal with different environments?

Right, and just see what you come back with. Like that Freddy Krueger shit where you can bring a 2x4 into a dream, and then come back with his glove or something. There's some quantum extraness to it. It's just a simple psychological, out of your comfort zone thing, but I feel like it takes on such a sci-fi dimension.

Have you always done that, tried to confront those feelings?

I never was that person. I didn't realize I was doing it, making a career of a thing that I didn't really know how to do. And to like skip the line, and not go to school, and not assist in a meaningful way. To just like show up and be like, yeah I can do this job, and have to figure a way out of it. I didn't realize that was what that was. But it really is, it's like Quantum Leap. That's my job, to leap into some new body, figure out how it works, figure out the social dynamics of a whole new group of people that I've never seen before, figure out what the problem is, and solve it in time to kiss the girl and leap into the next mess. It really feels like that. And luckily, I get to go home between the leaps, but I really have accidentally made a career of being nervous and uncomfortable, which I've always thought, even before this, was a really good compass point to follow. But I did it with much less enthusiasm for a long time.

Have you become more comfortable with it though?

I don't know that I'm more comfortable with it, I know it better. I have this claustrophobic recurring nightmare, where I'm entering a space, and as I enter a space, the opening, the doorway, becomes smaller and smaller and smaller, until it's this little rocky birth canal, and then I get stuck. And I've had that nightmare so many times, that now when I see the rocky thing, I'm like, “Fuck no, this is my nightmare, I'm not doing this, let's skip to a new part.” And I can do that in the dream, and I think it's like that. The experience of it is no less unsettling. It still does all the damage to my ego that it ever did, but I'm more sure of what's on the other side of it now.

It used to be, and it's recent enough that I talk about it as if it's still this way, but it's really not this way as much anymore. But I would take a job, a commercial job, like making shoe advertisements or something. That experience, that world was so far from my world. I would get in there and get so scrambled that for three months after I would have this identity crisis, an ego crisis. Am I actually good at anything? Have I just scammed... classic imposter syndrome, but a real thing. It would knock me off kilter for months. I would have to sweat it out on the street and go walk and walk and walk and walk, and then finally I wouldn't be able to see it as I was doing it, but at the end I was able to convert this terrible feeling into this body of work that reflects that terrible feeling and it was worth it. Now I'm just less put off by it because the opportunity is more steady and I've had more chances to go and be in that weird world.

Do you still seek out things because you know it's going do that to you?

Yeah, but not necessarily in those exact terms. It’s definitely a big litmus for me. I will always take a job where I can't imagine doing a good job. I'm given the parameters. I'm like, I have no idea how my brain will turn that into a good picture, and I'll force myself to take that job. Not in any kind of dashing way, I'm just like, “I want to go and see if I can figure it out.” I think that may be a bit of this underdog feeling having come into this business with such a kind of cheap route, like trap door entry, where I just get to like pop up in this position of prominence with no background that everyone else has worked so hard for. I feel like I need to constantly prove to myself that I should be here.

On the opposite end of that question, have you declined work? What kind of work are you just put off by now?

I don't like to really... exhaustively retreading old territory. I feel very sensitive to other people's inclination to kind of pigeonhole me. After the Met Gala, I always get a bunch of events offers, and you could totally package me as an offbeat events guy. I'll still do it if the money's good, but for the most part, I don't know, I know that world. It's sports. It's a short burst with an interesting crowd. There's not really much thought to it. It's all instinct, it's all chasing. I loved to do the Vogue job but I dunno, taking those event jobs over and over again it starts to really reduce me to something I don't want to be. And I don't mean in anybody else's perception. There is this kind of caveman setting, where I could just go around with a camera and clobber everybody and gobble them up like Pac-Man. That's fun once in a while with the right crowd, but it's really not an enriching activity. I guess I don't really think of it in such complicated terms. This is more afterthought, but I think that is my instinct. It's just not worth my time to retread. I want to make things hard for myself.

You used the term “body of work” earlier. You’ve had a couple of zines, a few shows here and there. Do you have books or shows in mind? Is that something on your mind?

I think about it, yes. Look, there's a big part of me that would love to have that kind of traditional classic punctuation where, I'm like, "I have now completed a project. Let me present it as this finished thoughtful thing." And, while I do have that brain somewhere in here… The real truth of this moment, maybe it will change, I hope it will change, but I keep saying it, and I really mean it, It's really not about the pictures. The process is so much more valuable to me than the results. It's really much more about this kind of personal challenge evolution time, where I had this crazy opportunity regularly to be in these very difficult places where I don't know what to do. So my focus right now is very hard to shift from tomorrow. Looking backwards, although it sometimes gives me some clarity about what I'm doing, it just doesn't hold my attention right now. I wish it did. I would love to make a book. I think I have good books in me, but I just am so much more interested in doing the work right now than in collecting it and making a statement.

“It's really not about the pictures. The process is much more valuable to me than the results.”

I also have had such an education. I started at such zero... I had that whole period where I was shooting everything out of focus. For like two years, everything out of focus. I still am so much in the business of fine-tuning this language and knowing what my picture even is. From the vantage point of, I'd much rather have this experience than contribute to the commerce of it. I'm just pretty wrapped up in making work right now, much more than looking back and figuring out what it is. I hope that shifts. I keep saying I need to break my legs, then I'll make a book. I just really love working.

Would you ever live anywhere other than New York at this point?

I wish. I don’t know if it will ever happen. Fifteen years went by very fast. Especially now, where New York has become home base as much as home, where I get to go all over the place and have an adventure and have this life where I'm seeking out discomfort. I think it becomes more and more important to have some comfortable familiar place to go and recharge. So, for now, I think I'm stuck with New York.

It sounds like if you ever to end up somewhere else, it would be something that just sort of happened naturally.

Yeah, which I would invite. I'm not determinedly full-time New York. If someone could trick me into moving to Paris, I would love them for it. But, I love New York. I can't believe that I've been just walking the street for fifteen years and I'm not bored. It's crazy. 15 years! That's so long to do something. And it's still new and still challenging. I mean I feel a little bit like I'm beating a dead horse sometimes…

But it's funny, it's worth mentioning in the context of a thing like this, that this whole notion of street photography, that every street photographer is so eager to dismiss. What it's become for me now that I have all these other curveball challenges to deal with, it's like it's boot camp. New York is just the perfect place to hone that instinct. To hone the instinct to be ready no matter what you're presented with so you can go anywhere. It makes you think of Frank Sinatra, make it here, make it anywhere, which is such nonsense. But in terms of my experience with learning how to be a photographer in New York, it really has been the case. I can survive these impossible situations where I have no idea what to do because I've just spent every day for the previous month walking down the street trying to figure out how to make a picture out of nothing. It's photo school. And it's funny because I think that people who go the whole photo school route, who learn the lighting, who learn whatever the hell ratio, I think there's a tendency to kind of bitterly dismiss street photography as snapshots, not photography. It's kind of a perfect match. Of course, you'd be bitter and bummed and you spent all that money to go to photo school, and school is just free outside your door if you have the patience and the time to put into it. Obviously, I’m not knocking anybody else's approach but I have this funny defensive instinct because I think a lot of people do want to dismiss this as a lesser, crude thing. And I think that's really missing the point. It's just a place to learn how to be in the world. It's not about the street. it just happens to be that the street in New York resets every 10th of a second and is always interesting and is always dynamic. It's just a great place to go and get that brain that can get you out of any kind of corner.