Jazoo Yang is probably best known for the Dots series, where she covers a home set for demolition with her thumbprint. In her homeland of Korea, the thumbprint—or “Jijang”—has a legal and personally binding power similar to a signature. With just a thumbprint, whole communities are turned over to destruction and gentrification.

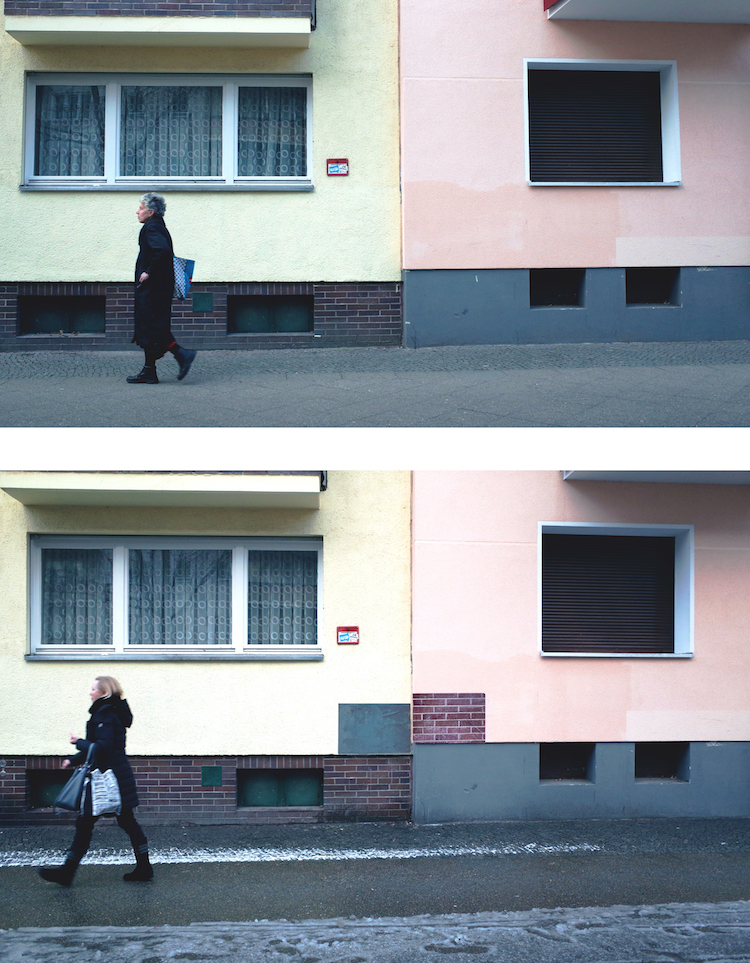

Upon moving to Berlin, Yang expanded her Dots series to incorporate the issue of refugees and migrants in Europe and beyond to explore the evolution of cities. Working with local immigrants, Yang discusses their stories, histories and day-to-day existence as they mark the wall together in a kind of folk song. In other series, she scrapes, gathers and re-assembles remnants of flaking paint, old wallpaper, rusted metal and the flotsam and jetsam of demolished and vacated sites, reconstituting them in the studio in acts of remembrance; time and memory sealed in resin.

We spent time together discussing art, politics, memory, loss and her place as one of the few female “urban interventionists” currently practicing on the streets of Europe.

Martyn Reed: Originally from South Korea and now working out of Berlin, what have you brought from that background to your current projects on the streets of Europe?

Jazoo Yang: I was a designer and founding member of Korea 's first web magazine Akzine, which covers the Korean independent scene and underground. After that, I spent time making documentary films.

My former house in Seoul was so narrow and small, and one day, I just wanted to paint, so I decided to go out, paint on the streets and make installations using abandoned objects. I met other artists, and in 2012, we created a project team called Seoul Urban Art Project. It was a contemporary urban art movement made up of street and graffiti artists, painters, illustrators, filmmakers and photographers. I had also met Brad Downey, The Wa, Akim, and Backjumps' Adrian Nabi, who have been living in Berlin. At the time, their work seemed very fresh to me and I enjoyed working with them. Those relationships led to my decision to move to Berlin.

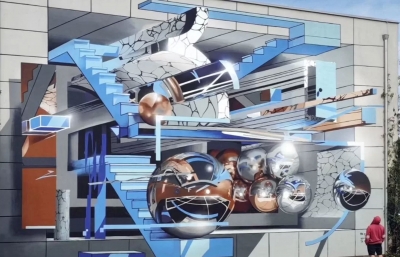

A city and its architecture obviously play important roles in your work. There’s a tentative relationship to muralism and street art, but conceptually, you’re much closer to what we’d call urban interventionism, which nurtures a viewer’s awareness of their surroundings. Is this something you research and play with?

The city was just a huge canvas to me at first. However, the experience of working on the street is quite different from the work done alone in the studio. I naturally come in contact with people and hear many stories about the site where I work, and at that time, redevelopment was happening throughout Seoul. It is and was easy to work because the development sites are prohibited from public access and the workers are resting at night or on weekends. I naturally chose that place to work, and as a result, came into contact with the residents and construction workers who lived in the development site. The stories I saw and heard on the field naturally affected my work, and the physically destructive situation caused by redevelopment was also very visually stimulating. It further amplified my interest in the material that makes up a city.

You seem to be interested in time, memory and the past, but not in a nostalgic way. However, there’s something both poetic and a little melancholic about how you treat walls and space. You treat the wall quite seriously.

I think it is because of the situation in Korea. For over ten years, South Korea has been very confused, both politically and socially. Redevelopment is one aspect. There is an old neighborhood called Ah Hyun-dong in Seoul, which was disappearing due to redevelopment, and I worked there for about two years because it was close to where I live. In the meantime, there was a case where a person who was opposed to the redevelopment got hit by an excavator and died. It happens often with conflicts between residents and construction companies; tragic events occur because proper compensation is not provided to the residents after redevelopment. However, I noticed that there was no coverage on any media. In fact, I didn’t know what was happening before I worked at the site.

In 2011, I had the opportunity to do a residency in Busan, at this place called Funny Revenge, a gathering place for subculture such as graffiti, hip hop and contemporary artists and activists. I became interested in politics because of the influence of the activists I met there. For many years, Korea has undergone a great upheaval, so I don't think it was special in my case to have gained political awareness, and the influence becomes revealed through the work. Moving to Berlin in 2017, I was able to focus purely on the material that makes up the city itself. The Re-Mix series was the first of many works created and inspired by moving to Berlin.

You’re probably best known for your Dots series of public art works, which were initially made up of your own fingerprints but went on to become more collective, incorporating refugees and other migrants. What was the initial concept behind creating the work, and how has it developed ?

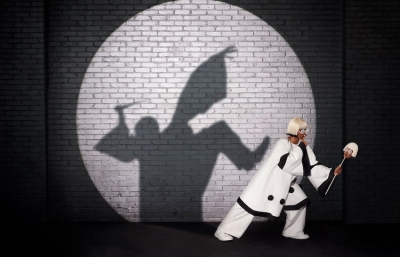

The first Dots work in Busan, South Korea, was done entirely by myself. It was the result of the direct and indirect experiences of not being able to catch up with the pace of the ever-changing metropolis, and it was also an attempt to heal the trauma caused by the Sewol ferry incident. In St. Petersburg, during the exhibition Crossing Borders/Crossing Boundaries, the theme was extended to the subject of European migrants and refugee issues, including the situation in Korea. I imprinted fingerprints on the outer walls of the Street Art Museum with six illegal migrant workers in St Petersburg. While imprinting our fingerprints, we talked about our lives and memories as individuals, apart from the history or existence as refugees, migrants or artists.

When I did the Dots in Besançon, France, that was the moment when the work really evolved into a dimension beyond myself. More than 200 people, including refugees who are legal residents in Besançon, immigrants, tourists from many different cities and countries, and local residents voluntarily participated in the production of a mural. If the works within the Dots series in South Korea and Russia were about me, the mural in France is purely about other people, about citizens. I would talk with them while they imprinted their fingerprints, and perhaps this work seems to have a different meaning depending on the people and where it is done.

I saw how lovingly you scraped pieces of dried and flaking paint from the walls during Nuart, some, of course, which were painted by visiting artists and then painted over again and again. There’s history in the walls. I get a sense of loss from your work. Is this a feeling you recognize and try and generate in the viewer ?

I try not to present something in my practice. It's not a representation of my ideas, but a reaction of my senses about things. The rust, decay, corroded wall traces, old posters, and peeled paint shells that occur over time can be associated with a sense of loss. However, when time is included as part of work, the loss can acquire permanence.

It reminds me of the concepts around Hauntology, which, I guess, could be best described as the memory of a lost future, the crackle of vinyl used in contemporary electronic music by the likes of Burial, for example. Do you have a relationship to techno and electronic music?

There is a sense of retrospective texture linked to how I choose materials, but I don’t know if there is a part of the method of techno or electronic music that I directly identify with my practice. I like the sensibilities of Portishead, Massive Attack and David Lynch.

Your most recent series, Stolen Times, where you use peeling paint from walls and abandoned objects and reconfigure them into studio artworks—do you also use the same technique for creating street pieces?

Yes. Mostly, I collect materials everywhere I go. Since the characteristics of each city and street are different, it is possible to collect materials of slightly different texture and color. I use what I collect on the site and bring the materials to the studio and continue to work. Street pieces are more influenced by the surrounding environment. There are some moments and points that are accidentally found as I move through the streets. Installing work in the white cube is similar, but there are many more things to consider on the street.

A monograph of Jazoo Yang’s work will be released in 2019.

jazooyang.com

This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 issue