It’s not difficult to understand why Lucy Sparrow has become a bit of a rock star in recent years. Although I absolutely love a good opening and get excited when an artist I follow has a new body of work to share, the urgency that you have to be there, you need to see it, only comes around every so often. An exhibition may speak to you, but there are few artists who cross over into evoking a compulsion to experience their work in person no matter what. This is the space Lucy Sparrow occupies. She is a must-see. It doesn’t quite make sense, the volume, repetition and little intricacies and individuality of seeing 30,000 pieces of art before you. Made of felt. Not only objects made of felt, but entire corner stores, sex shops, grocery stores, bodegas, you name it, where every object you have spent your life consuming and seeing advertised, is presented, and made of felt. It’s mesmerizing, a bit maddening really, to even begin to consider the stamina it takes to actually make the work, and intuitively how whip-smart Sparrow’s art-making is. Not only is it a multi-faceted comment on consumerism, but a challenge to what the art-buying market really is. You may wonder, “Why on Earth would someone do this?” But by the time you’ve posed the question, you’ve bought a felt box of Cheerios and had the best time doing it.

Lucy Sparrow’s approach is something that, perhaps in the past, might have raised an eyebrow or two. Is it performance art? Conceptual art? Art made for Instagram? A souvenir? Feminist? Political? Of course, the answer is that it is some, none, and all of those things. Watching thousands of people come through Sparrow Mart at the Juxtapoz Clubhouse in Miami in late 2018, there didn’t seem to be one person who wanted to be there for any of the above reasons. They wanted to see felt. They wanted to see their childhood memories or daily lives reimagined and repackaged by a talented artist who also becomes the centerpiece of the exhibit. In considering the most polarizing performance artists of our time, Chris Burden, Marina Abramovic, or even Cindy Sherman, finding herself to be the material of her own work, the realization occurs that Sparrow doesn’t fit into those categories either. I would even argue that she is beginning to create her own genre, one that takes the popularity of street art, the headiness of conceptual art, and the hyper-super-modern social media world, and turns it into unreplicatable, original and interactive installation art. And the best part? You can take a little bit home with you.

I love this idea of artists creating work that ignores the fashion of the era. Emily Mae Smith, interviewed in this issue, pointedly observes that, “There was a whole period of time in the past ten years in New York where if you made representational painting, it was not cool. Nobody was showing it. That was a weird micro-trend, but a very strong one. It was just all abstract.” And you know what Smith did? She adamantly painted image-based work. She didn’t care about the trends: she just made good work and knew that time would tell the truth. Consider Julie Curtiss touching on Surrealism, Neo Rauch being a figurative painter of nearly his own genre, or Vaughn Spann mixing abstraction and portraits in the same exhibitions, side-by-side—it’s not about doing what you are told, or doing what trends say is smart and sensible. So the next time you notice an artist doing work “off-trend,” chances are, that artist is doing it best. —Evan Pricco

Enjoy Spring 2019. Get the issue here.

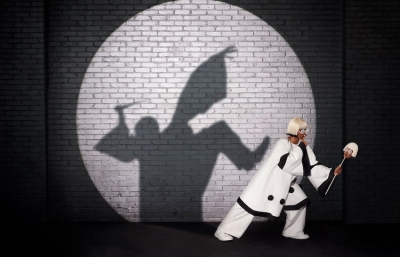

Above photo by Ian Cox. Lucy Sparrow took Ian's original portrait of her and transformed it into a felt artwork, which we then used as the cover art.