In an ableist, supremely white world that works to eradicate and kill Black, disabled, and neurodivergent, there are persistent voices like Jen White-Johnson, who fights back with resistance, joy, and hope in her artwork, design, and activism. In these increasingly fascist and eugenic times, White-Johnson finds deep self-love and inspiration in her son and other disability justice activists. Her work gave me, the interviewer, the strength to continue being true and clear about the importance of disabled Black Indigenous Queer Trans People of Color experiences. Our interview is a record of how one performs this disability justice work through art and design.

Iris Xie: You’ve done an enormous amount of work connecting, drawing inspiration, and building solidarity with other disabled activists, translating their work to visual communication design. What do you find fulfilling in that radical practice work, and how does care work factor into it?

Jen White-Johnson: When I started to feel comfortable identifying as someone who has a disability and is neurodivergent, who parents someone who is also neurodivergent, I started to realize that design can begin to be used in a very celebratory, uplifting way. To me, that’s the whole point of design and art, to help you feel that you have a collective responsibility, and to help people feel valued, understood, and seen. So I feel that my work naturally became rooted in advocacy, as a result of not necessarily feeling that I was seen.

What is a memorable experience you’ve had that has validated your approach and success in your art and design practice, as well as advocacy work?

The day I became a mother to my son. Both he and I aren’t supposed to be here since my birthing experience was quite traumatic. Unfortunately, this is often the tale of many Black mothers, due to preeclampsia/eclampsia being the leading cause of maternal death among Black women. Black Women are five times more likely to die from pregnancy-related disorders than White women. I am grateful to have survived alongside my son Knox, which makes our purpose and reason for existing powerful.

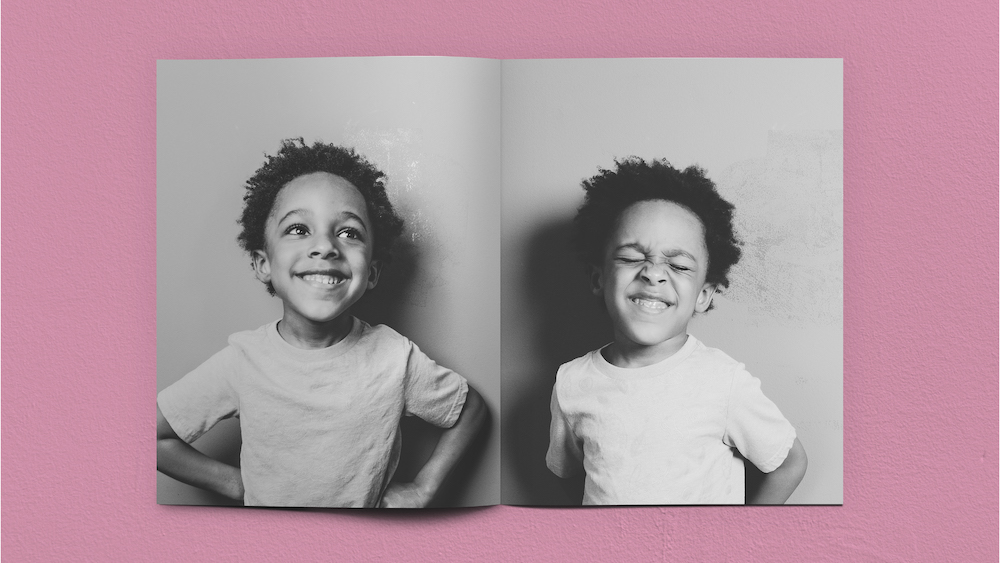

I also have, framed in my house, the tweet of Mariah Carey retweeting Knox when the Queen of Christmas invited us to her Madison Square Garden concert! It’s beautiful to see him be unapologetically autistic and expressive in the way he feels with his whole body. He does it at home, and it was really beautiful to watch him at his elementary school choir concert, taking center stage and singing “All I Want For Christmas Is You.”

It was a big win for both the entire autistic community and the Black autistic community to see him being praised and uplifted, including his joy going viral for all the right reasons, to spotlight autistic joy versus this constant demonization and infantilization of Black and autistic kids.

Tell us more about Knox and what would you like us to know about him, including how he informs and collaborates with you in your practice.

Knox is art. He is the greatest gift. He is my ten-year-old son who was born at just two pounds. He is also an amazing Autistic human. Knox’s unbridled glee is infectious. From the very beginning of his life, I have worked to make sure I give him the tools to be confident and comfortable in his identity, disability, and the beauty of the person he is and who he’ll become.

Could you take us through some of your creative processes?

Well, in my photography I love being able to document sensory experiences like how Knox reacts with materials, how his body responds, his smiles, and the way he laughs. There's so much about my process that is about documenting the joy that I see and want to uplift. Like him playing and stepping into this huge sensory sock, stretching the fabric, which is this really beautiful bright blue.

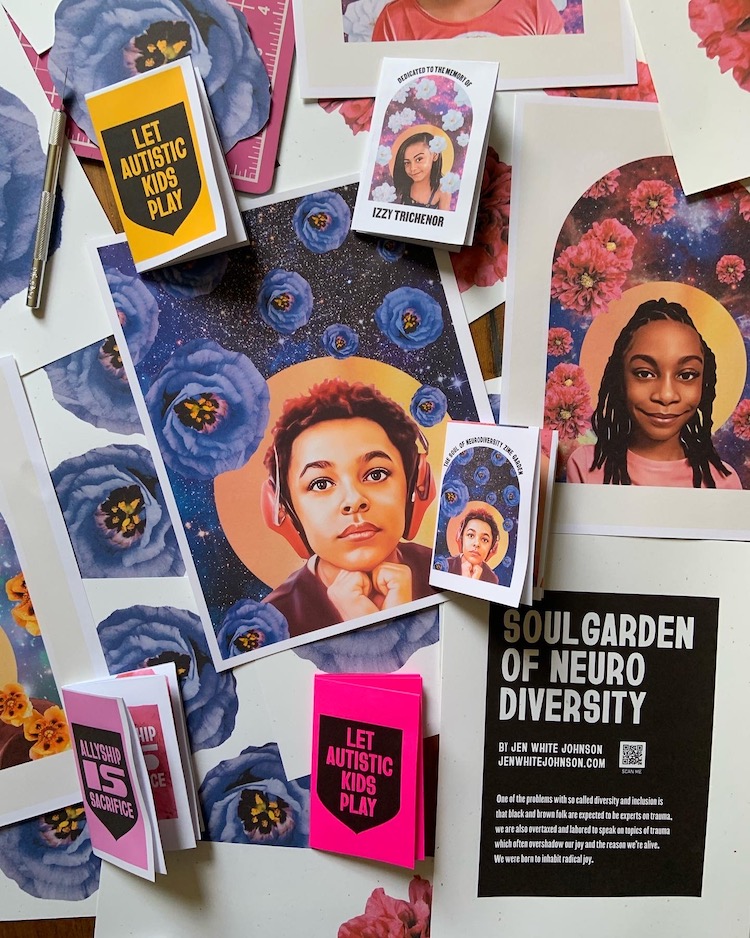

My digital collages are about finding images of figures like Nina Simone, or disability justice activists like Anita Cameron, Fannie Lou Hamer, Alice Wong, and Stacey Park Milbern. Holding space for these collages which give these amazing humans the flowers that they deserve. I feel we rely so much on these traumatic narratives, to get people to care; and it's like, yeah, but what happens if we don't necessarily focus on that trauma? What if we honor folks, while they were still very much alive and well?

What is personal, meaningful, and visible representation to you, in the context of naming Black disabled lives, access, and care work?

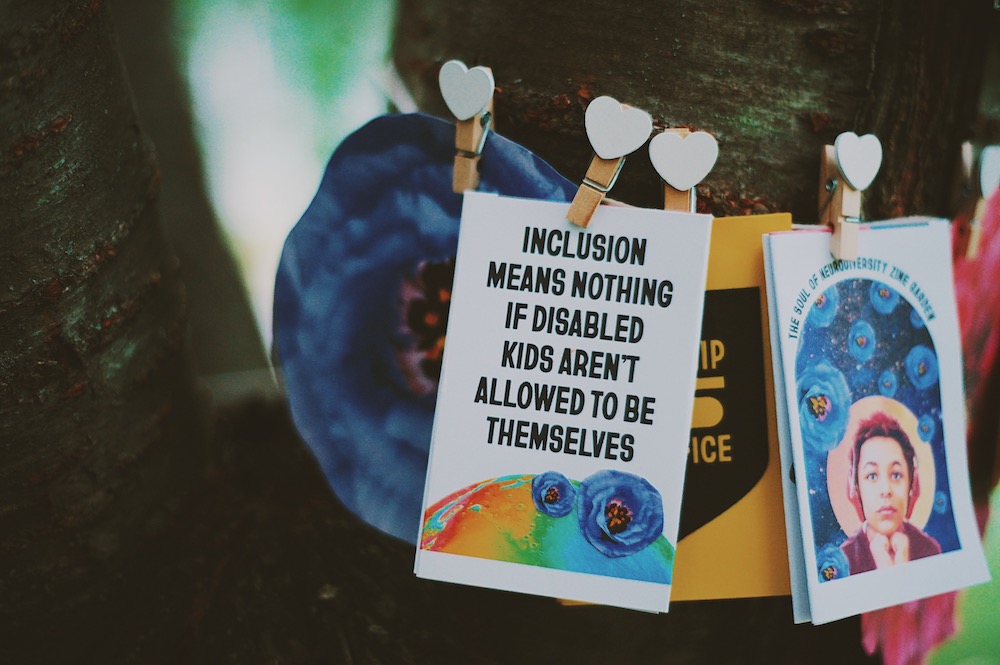

I define visible and just representation as a place where disabled folks aren’t just “included” and “allowed” to be in the room, but where we’re encouraged to become the leaders we’re meant to be. Where we’re not only given the tools to lead but given the ability to build and create our own tools to lead and teach others along the way.

Art and Design is my weapon; it’s the armor I use as systems of oppression are constantly being set against me. Many don’t understand that fighting ableism means war—especially when Black and Brown disabled kids are being demonized and dehumanized in academic institutions and in their communities.

Can you tell us about the #BlackAutisticJoy hashtag?

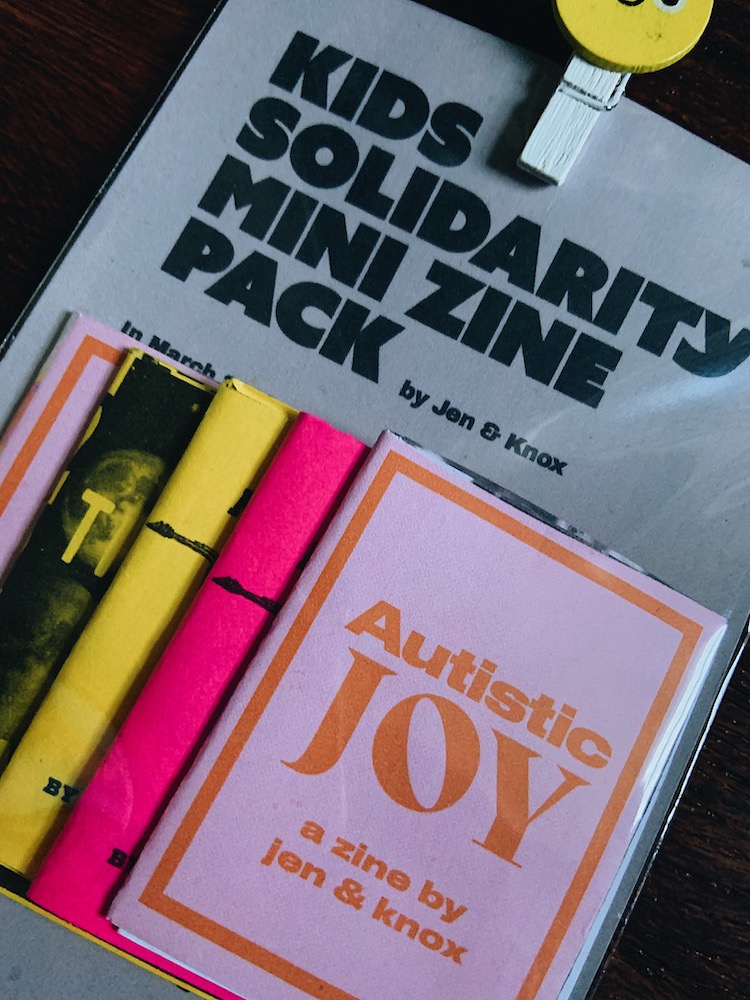

Originally I used #AutisticJoy, as I was directly inspired by Knox’s autistic joy, and I started using the hashtag whenever I would post footage or artwork that I was creating especially in honor of my autistic comrades. I also noted other Black autistic advocates like Timotheus “T.J” Gordon Jr and Kayla Smith. I really feel validated to recognize this kinship and this beautiful alignment with other Black Autistics because they're role models for Knox. They were able to see direct reflections of themselves through his joy, and they were like, wow, we're so excited to see you!

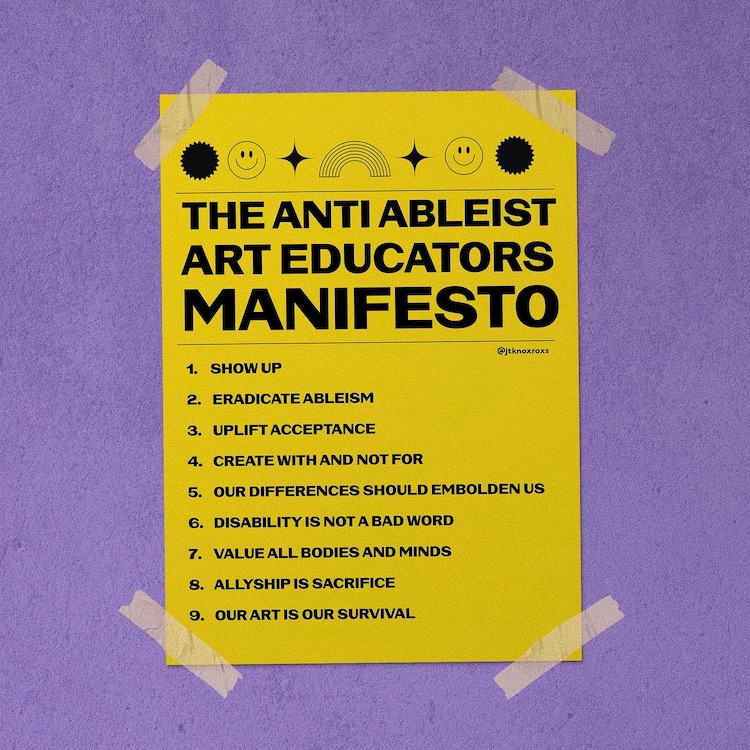

The Anti-Ableist Art Educators Manifesto in both English and Spanish is a powerful pedagogical tool. Could you tell us about the story behind it?

Recently, I’ve transitioned from the grind of full-time teaching, and my career has taken a shift as I’ve begun prioritizing advocacy and activism. As a disabled and neurodivergent mother, artist, and designer, I’ve noticed that internalized ableism occasionally creeps in, wanting to control and degrade my creativity. This Manifesto is meant to serve as a direct act of creative resistance, protest, and radical pedagogy designed to help the disabled and non-disabled community become more aware of how to uplift their disabled selves and their fellow disabled and neurodivergent students inside and outside the classroom. I really see the Manifesto as my way to amplify access and abolish ableism, designing to embolden disability visual culture In the classroom and beyond.

I wonder how you can situate your work in how it creates Black Disabled Futures and disabled Black creativity, as it resists the dehumanization of disabled Black children.

What is accessible for me is to make sure that my art names and incorporates the actual word, whether it’s saying “Black Disabled Lives Matter” or creating statements like “Create More Anti-Ableist Spaces,” “Autistic Joy,” “Radical Joy,” and naming words like neurodiversity and holding space for disability amplification. This includes wheat pasting posters, zine workshops, and protest graphics I’m sharing on social media in materials like the Anti-Ableist Art Educators Manifesto. This includes fun toolkits with visuals that highlight Black disabled feminists, and disabled folks of color.

Our lives are at stake, and our art is our method of survival. We aren’t going to have that visibility unless we are willing to name the fact that we are disabled. I create artmaking activities so everyone can understand how to uplift disability culture and learn to prioritize naming folks and identify anti-ableism into the artwork they're creating. Art and design is my ultimate space for liberating folks, a way to honor those who have liberated me and paved the way so that I can continue creating the artwork and the design that I envision.

One of the major challenges as a multiply marginalized artist, designer, and activist is that you and I inhabit all these experiences that are shared by the community. How do you create your work while living in an ableist, white supremacist world?

I feel like I don't get caught up in creating the perfect work. I just want to create the most honest and authentic responses to let those folks know like, Oh, I see you, and you're helping to just make my point all the more relevant and correct and important.

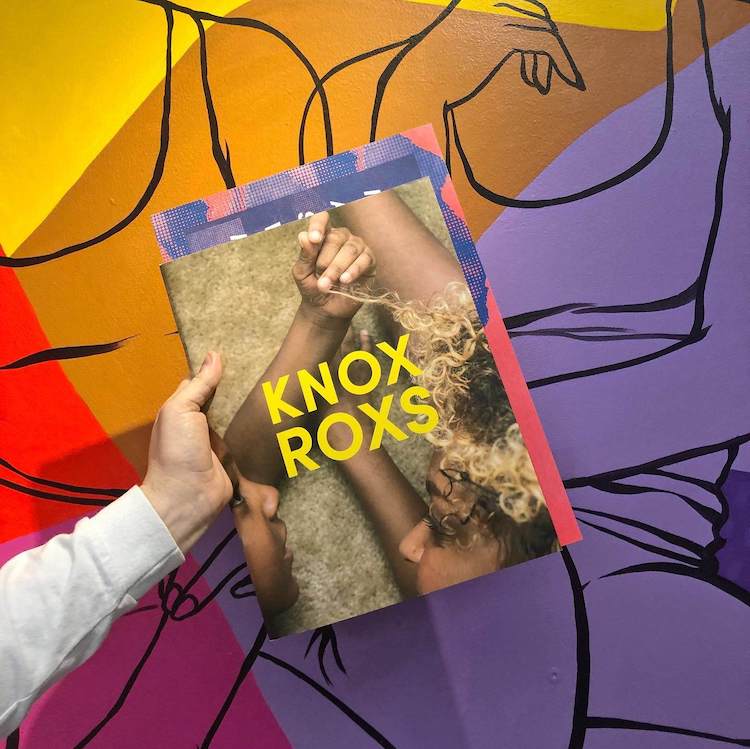

After I released my first photo zine, “KnoxRoxs” that really helped to specifically uplift neurodivergency within Black families. And when I was uplifting and promoting my visual resistance, I was also sharing videos of Knox, you know, dancing and stimming and being very unapologetic to say, hey, like, here's the world in which we live. Here are the safe spaces that we're building and creating with our son, and folks were saying, “This isn't stimming, stimming is harmful. Stimming is what we need to eliminate and eradicate, and to be controlled” and that our kids have to move their bodies and behave in “correct” ways.

I was getting those responses very specifically from white folks within the autism and special needs community asking, “Why is your child dancing erratically? He just looks silly, this isn’t enjoyable, why would you want your child to do that?” They are trying to challenge his definition of autistic joy and sensory joy and trying to dictate how a Black neurodivergent mother should hold space for her Black neurodivergent child. We Black people express ourselves through movement and the voices of our ancestors, and when I see my son singing, I see him joyful. That’s us summoning our ancestors and reclaiming everything they’ve done for us. It's a much deeper conversation, so when you have white supremacy completely trying to eradicate and dehumanize our children, that gives me so much fuel to resist.

Mothering is an act of resistance. Folks will tell me not to waste my time responding, but how I also respond is with more art, more footage, and being unapologetic about how this is my world as I stick to what brings us joy and what makes us feel safe. My autistic friends, who stim as art and sensory experience and expression, were resisting together with me, saying, “No, stimming is joy, like stimming can be really beautiful.” It’s an expression of what exactly Knox is feeling, outside of that box of normative behavior.

Iris Xie is a disabled and neurodivergent queer trans nonbinary Chinese-American multi-discipline writer, artist, and designer from the Bay Area, currently based near Sacramento, California.

You can see more of White-Johnson’s work at jenwhitejohnson.com // This interview was originally published in the Summer 2023 Quarterly