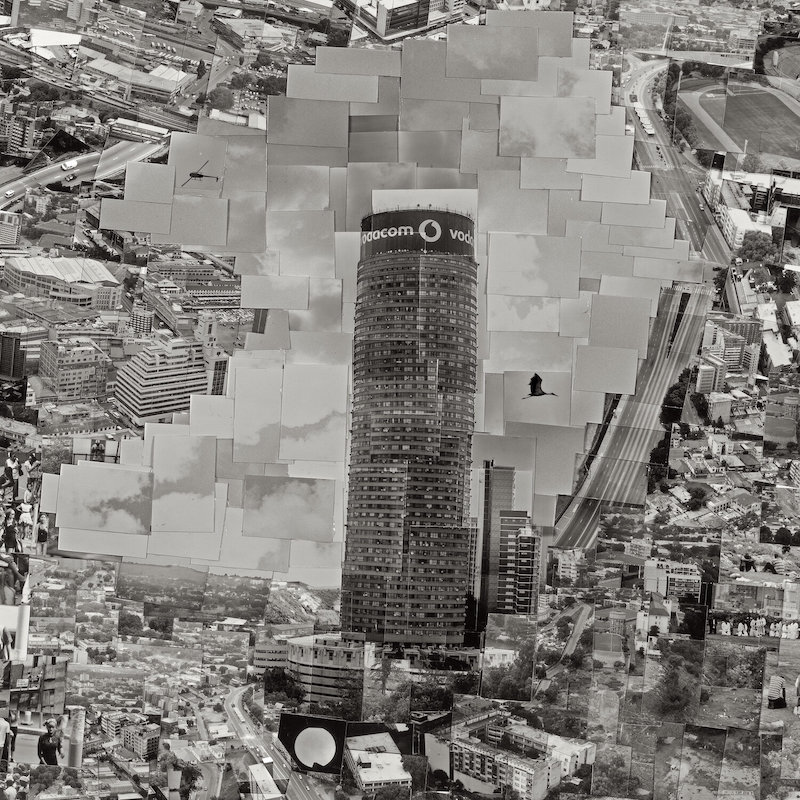

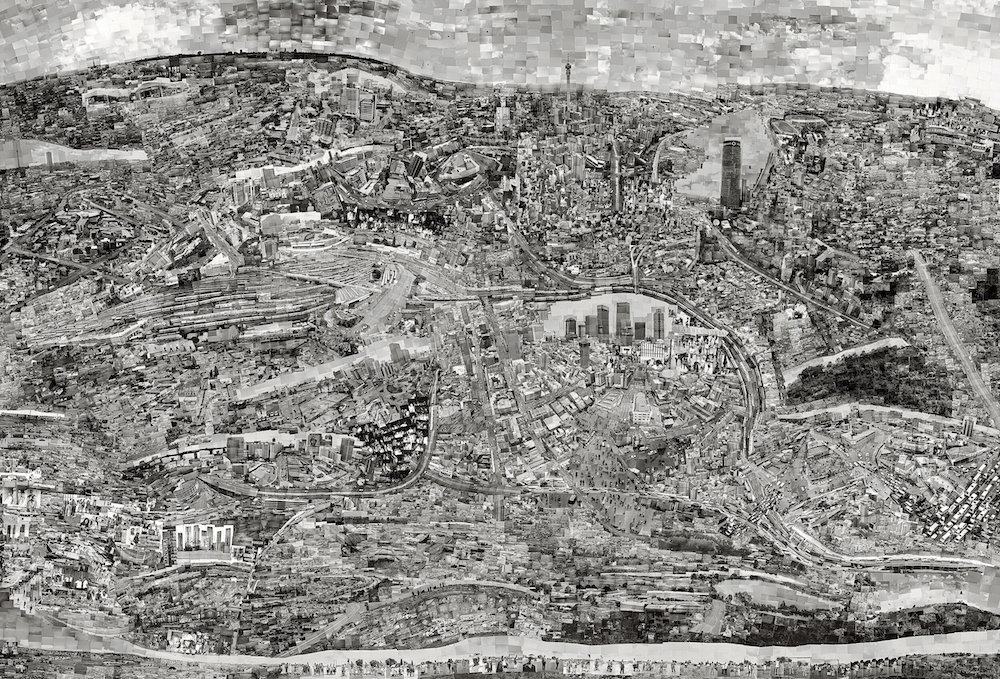

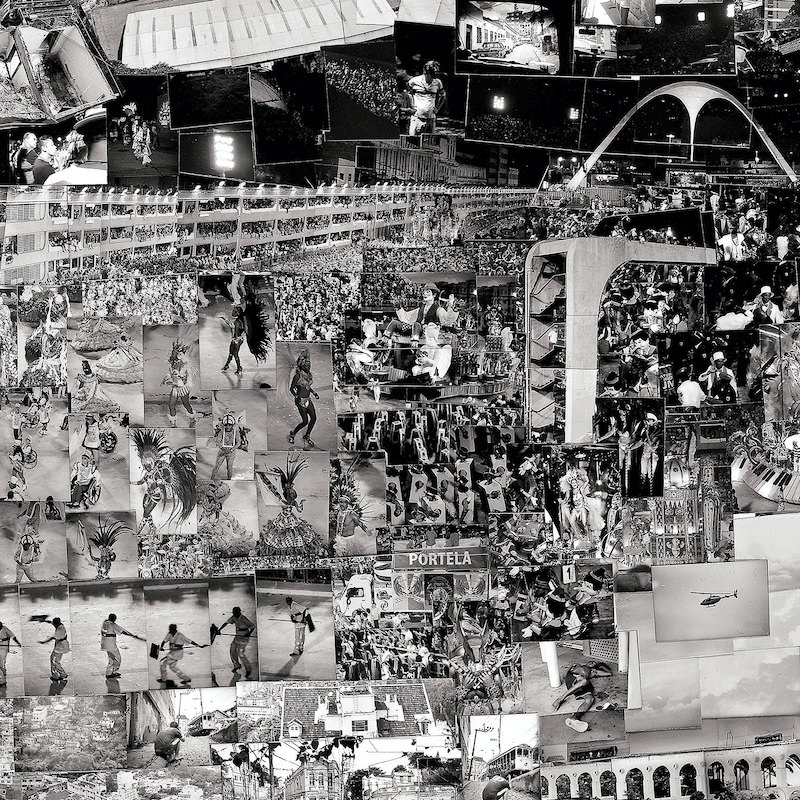

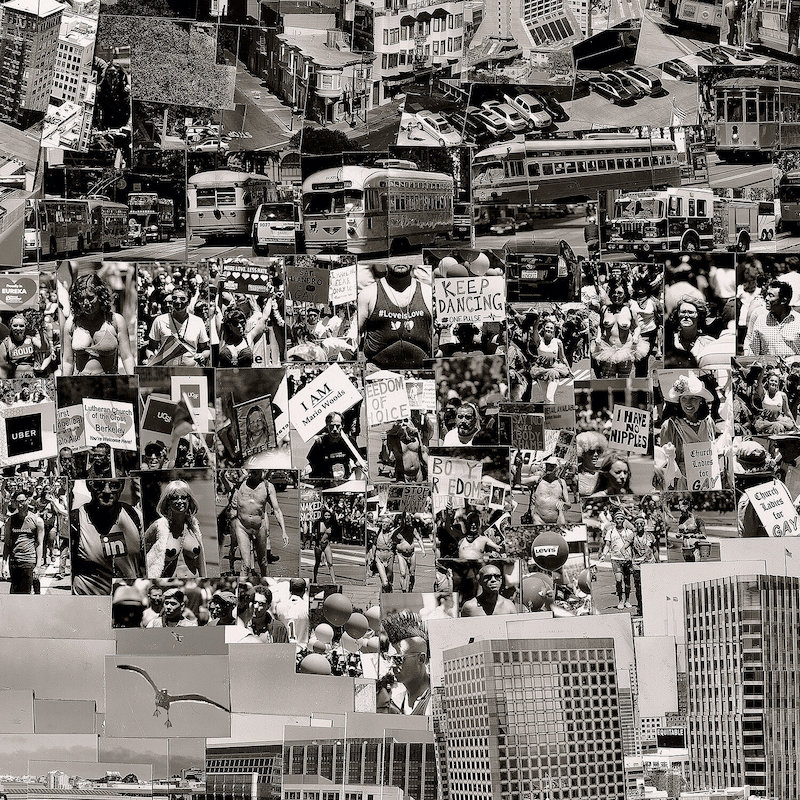

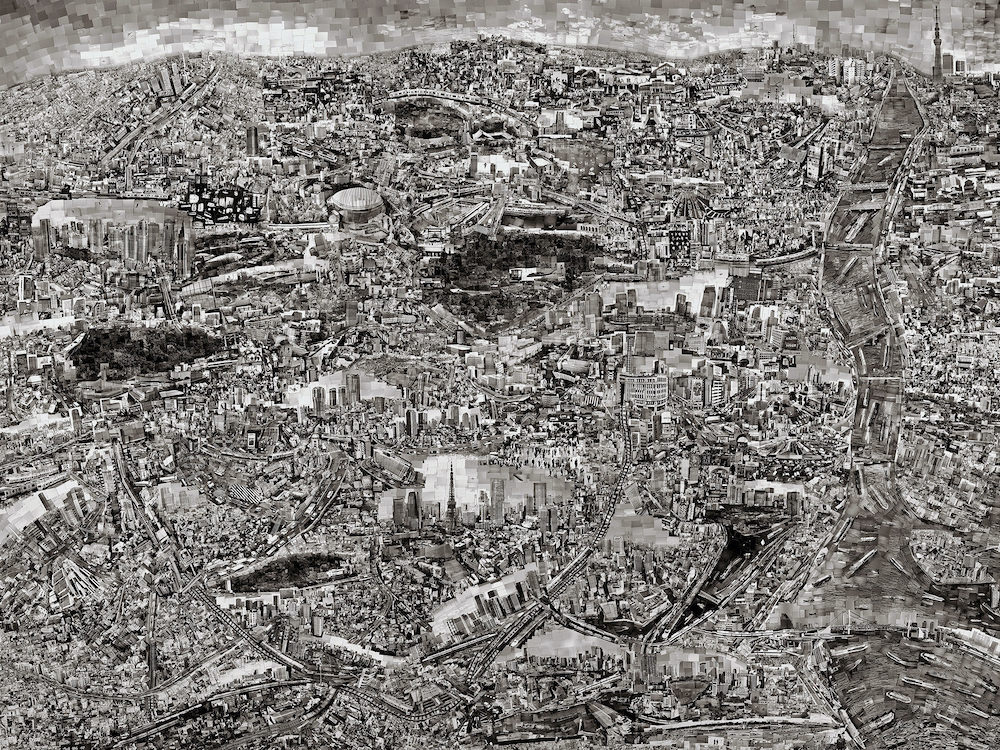

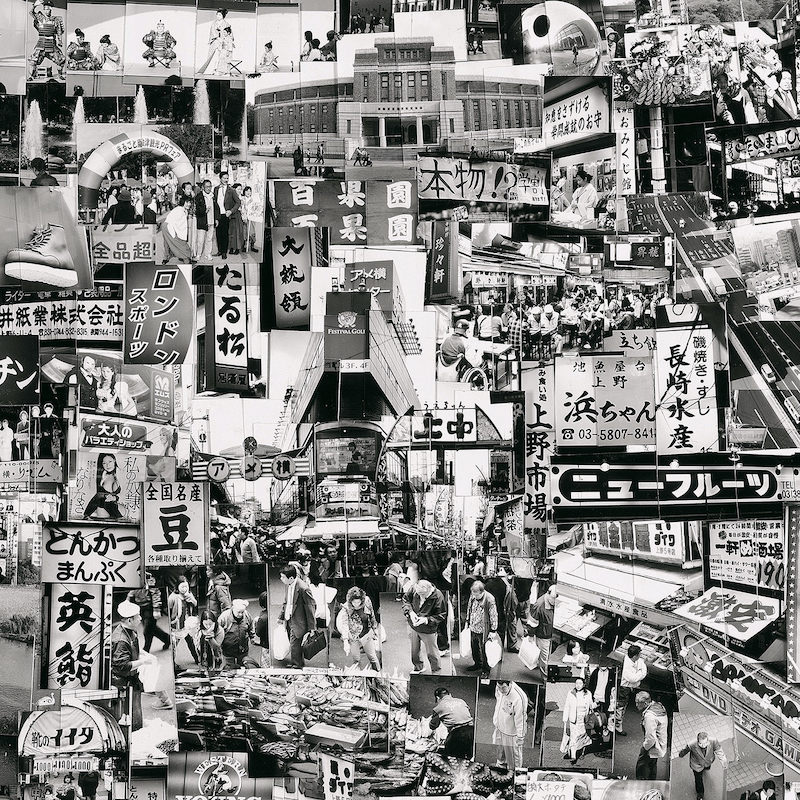

Our memories are intimately tied to photographs. Whether a childhood portrait or sunset selfie, the photograph represents not just the captured moment, but how that moment is currently remembered. It’s nearly impossible to separate memory from the reality of experience. Walking down the street, we ignore one thing and gravitate towards another, while landmarks anchor us within a geographical space. But what captures or escapes our attention defines our recollection of that place. Japanese photographer Sohei Nishino’s work encapsulates this transient relationship between personal experience, memory, and place. Photography, like memory, is also defined by what is included or excluded from the frame. Like any curious photographer, Nishino weaves his way through each new city, making decisions about how to portray his surroundings. “When I’m shooting,” he says, “I am always thinking about what I’m trying to see within the events in front of me, what I am focusing on and how I feel about it.” An individual image can anchor the portrayal, but it’s how each fragment is pieced together that defines the journey and transports Nishino’s work into an expansive new realm.

Shooting only film, Nishino places great importance on the labor-intensive process of developing, printing, cutting, and assembling the images. “I think I need an appropriate amount of time to process the enormous amount of experiences that I have while shooting.” The permanence of the film photograph, he explains, “allows me to separate the reality of the world from that which I was dreaming of.” Collaged frames propel us from one scene to the next, giving form to shifting landscapes, telling stories, or offering necessary perspective. Together, the photos reconstruct memory, as they contradict, renew and shape a wider understanding of places visited. We recall the old man singing on the subway yesterday as we board it today. We dread tomorrow’s commute as we sit in traffic tonight. We move forward through time in an experience that is rarely linear.

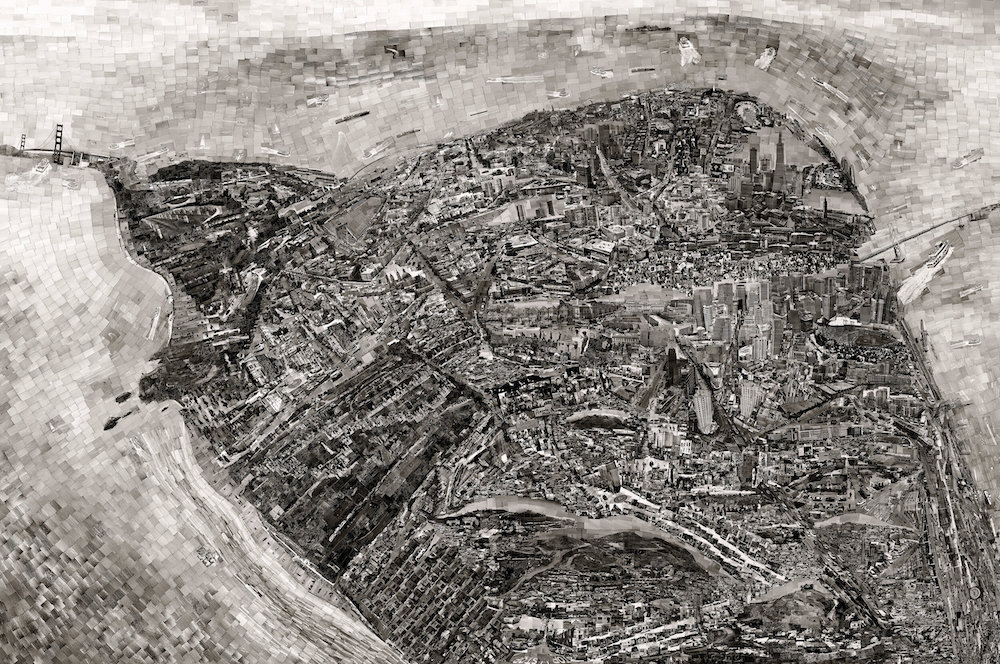

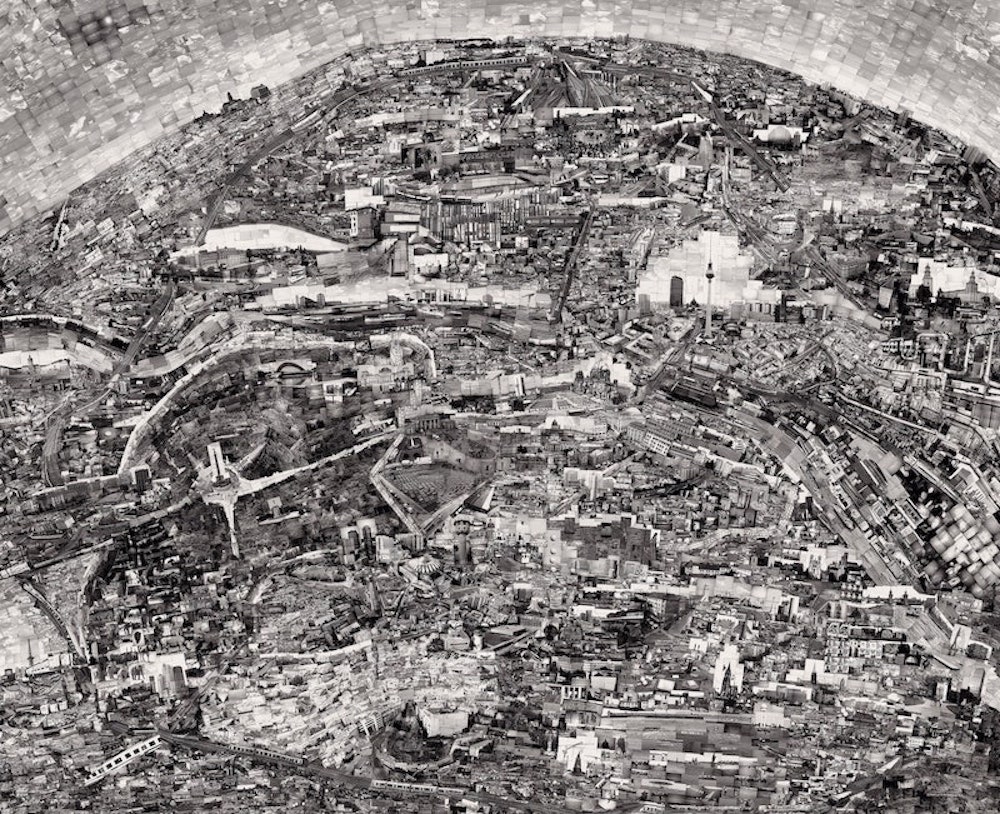

Maps help us navigate as much as they allow us to picture the otherwise incomprehensible scale of the world around us. Nishino’s diorama maps comprehend the spectacular breadth of experiences, lives and perspectives contained within a place. “This work was born from my desire to understand human beings by looking at cities,” he says. “When I dive into a place and its people, food, scenery, culture, language, and sounds, I start to feel my body becoming empty.” It’s a sensation he attributes to philosopher Walter Benjamin’s description of the flâneur, a joyful, empathetic character intoxicated by the city and propelled to wander its streets. Seeing his topographical portrayals, we confront the vastness of the city and are ourselves intoxicated, propelled, in movement and moment through the pieces of an ever-evolving panorama. Sohei Nishino’s maps don’t necessarily help us find our way from point A to point B but provide an opportunity to appreciate the rest of the alphabet. We are given both experience and its context, both the forest and the trees. —Alex Nicholson