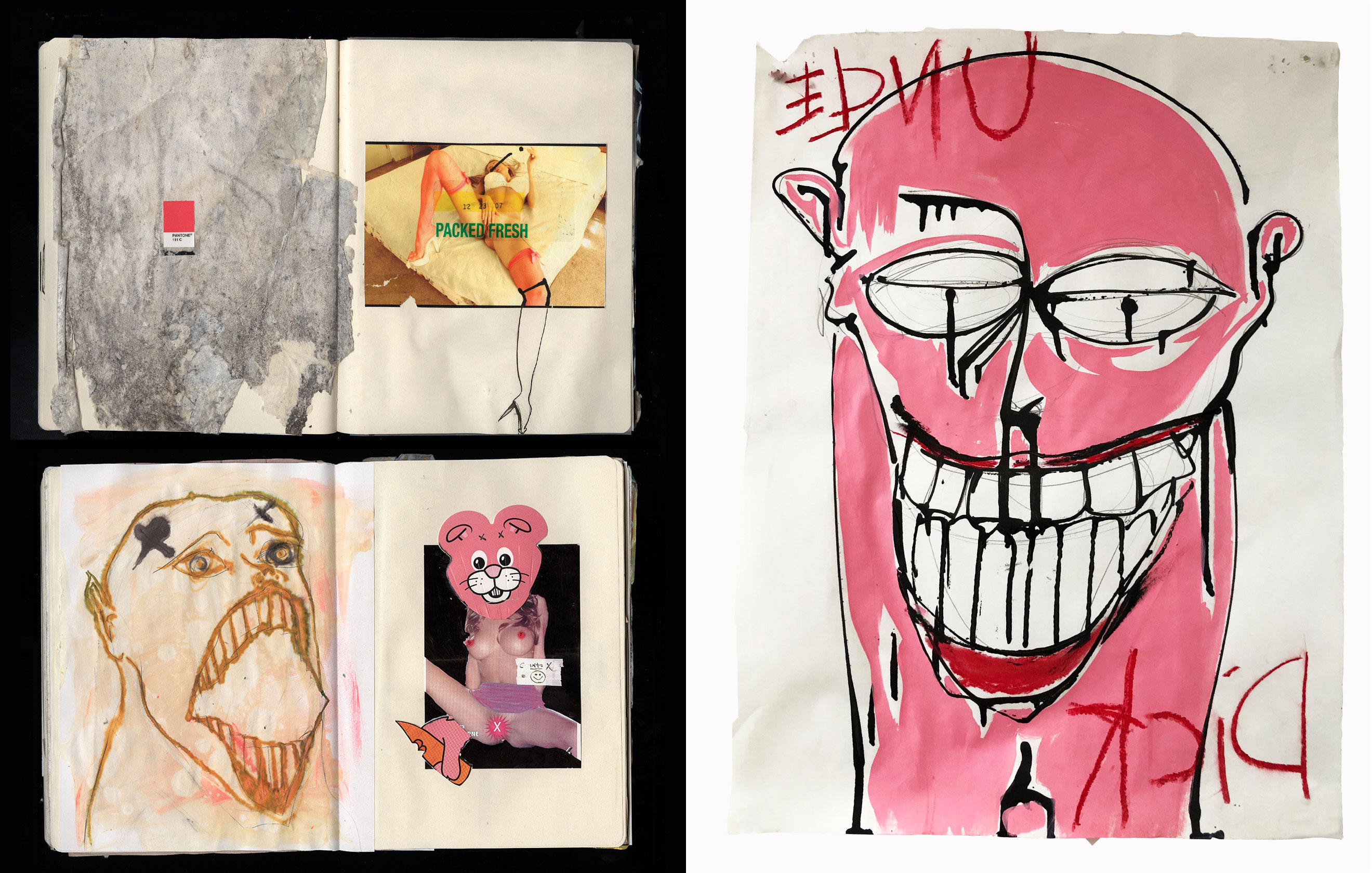

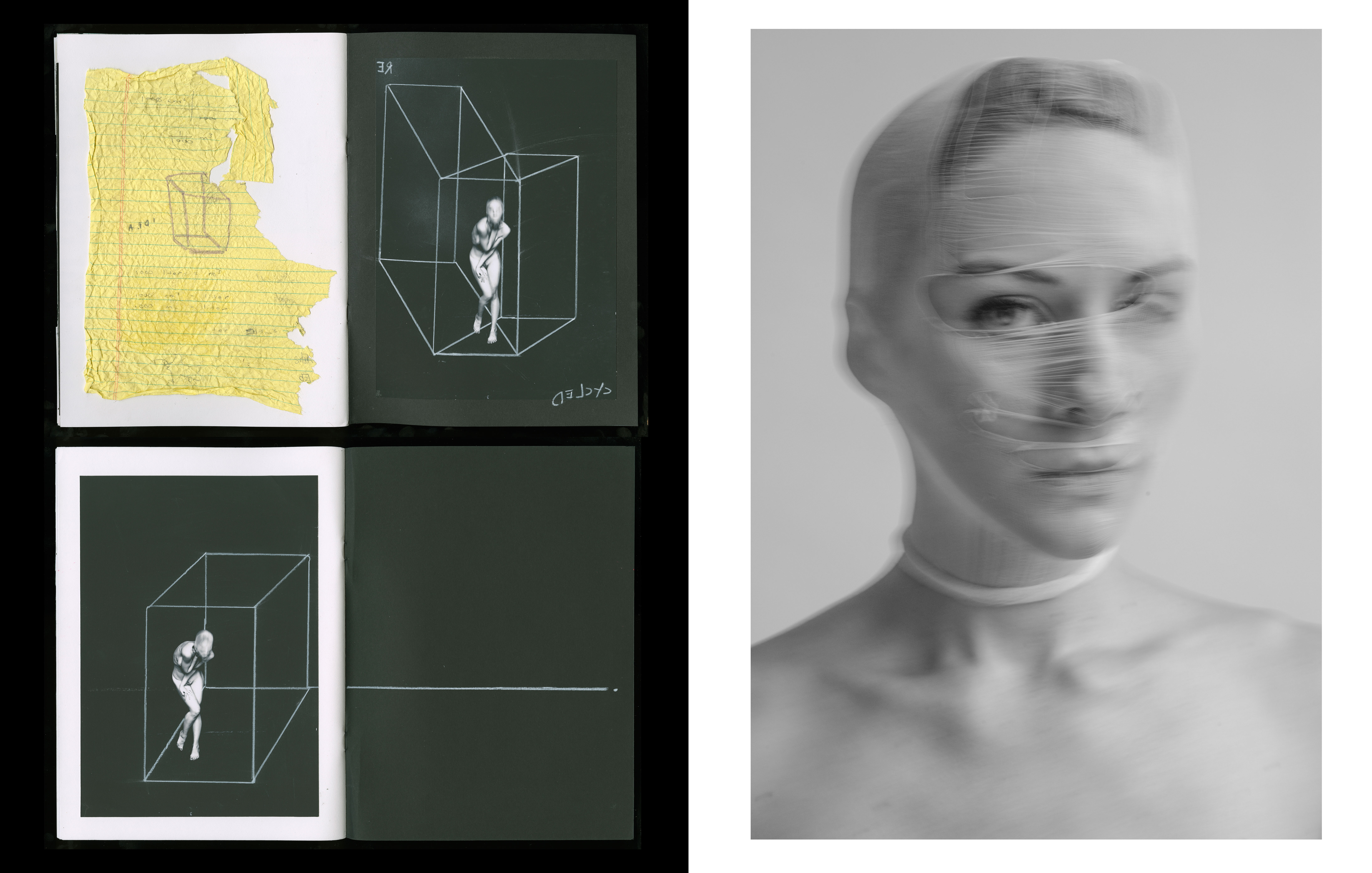

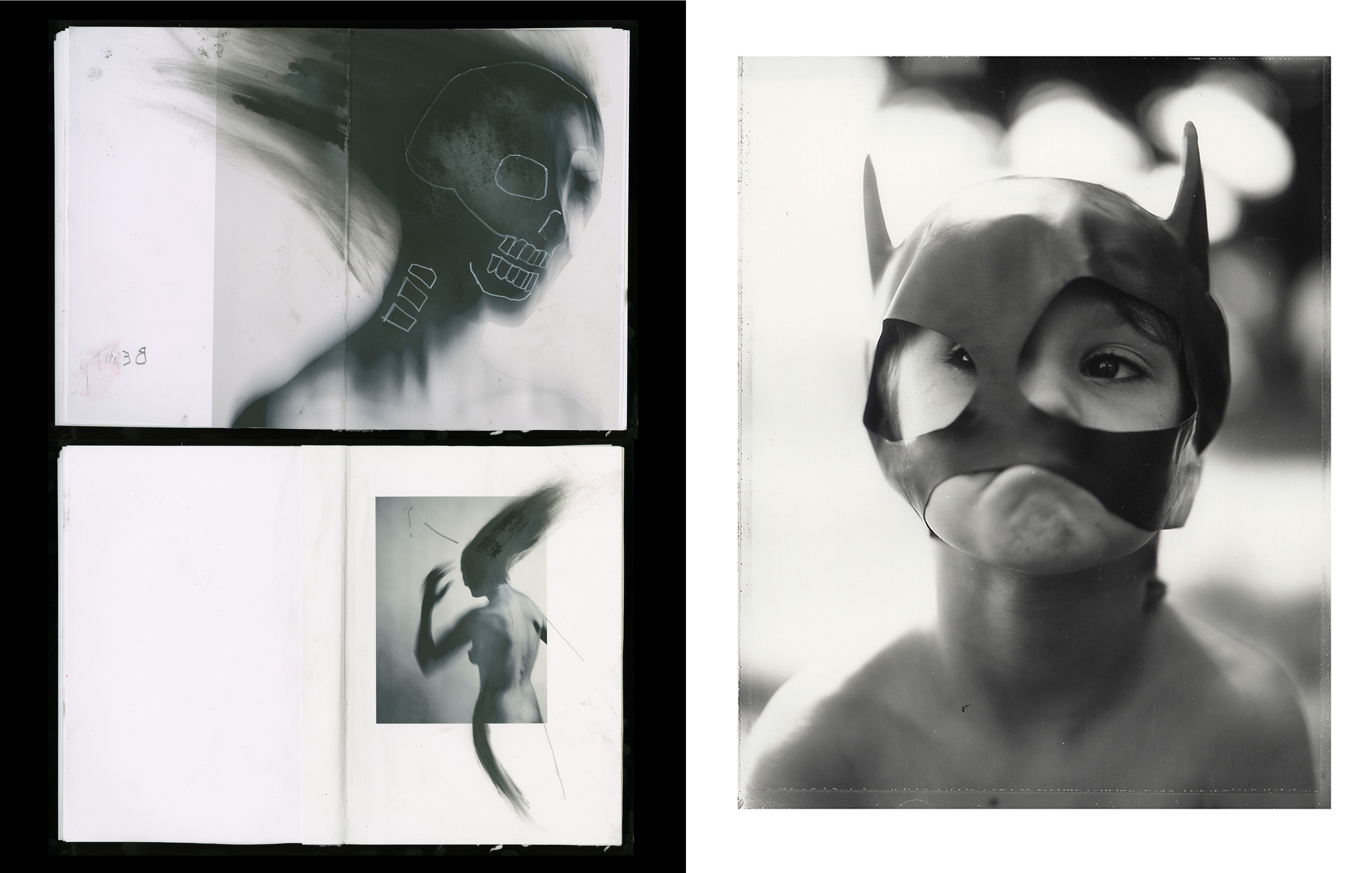

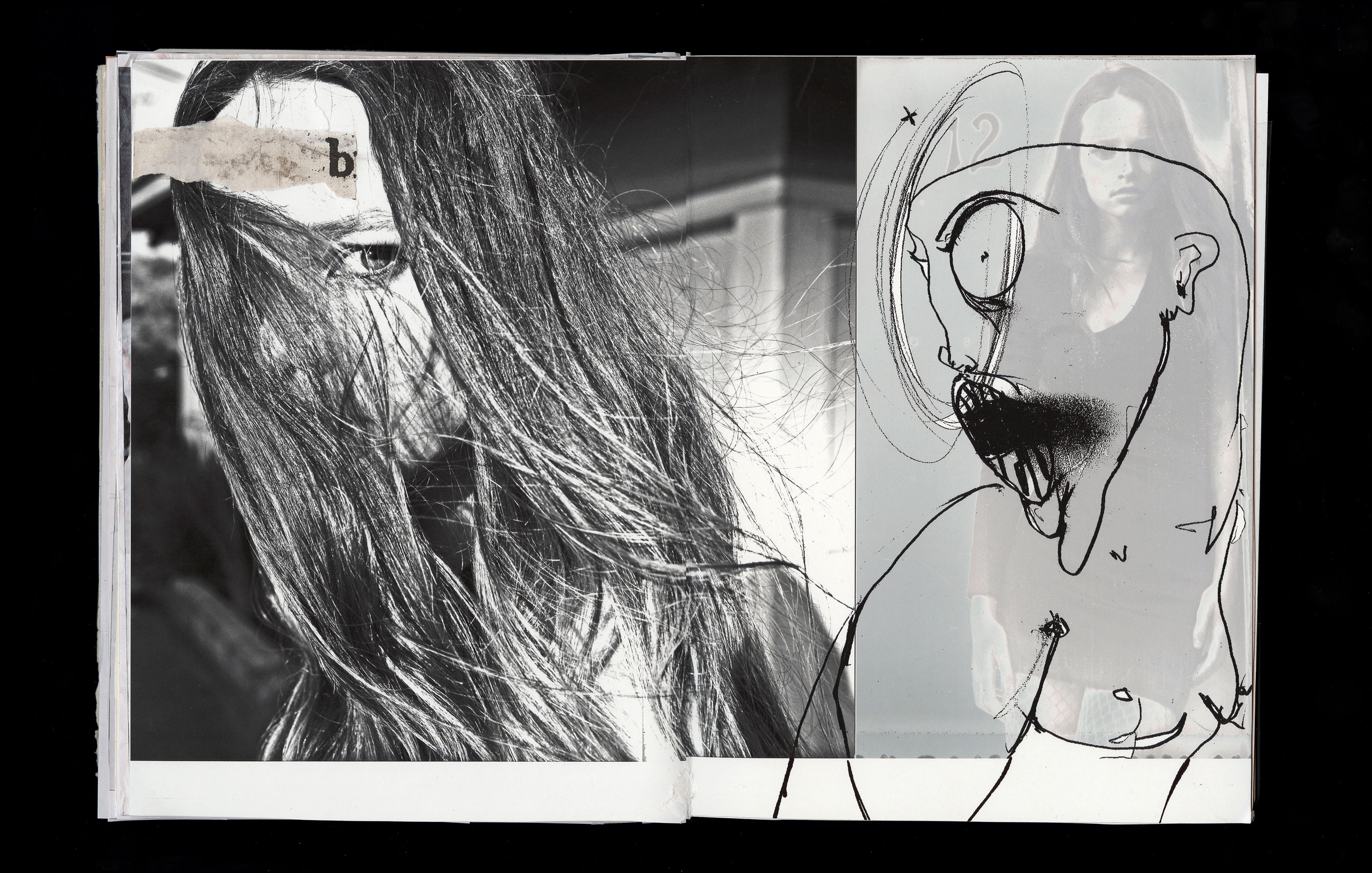

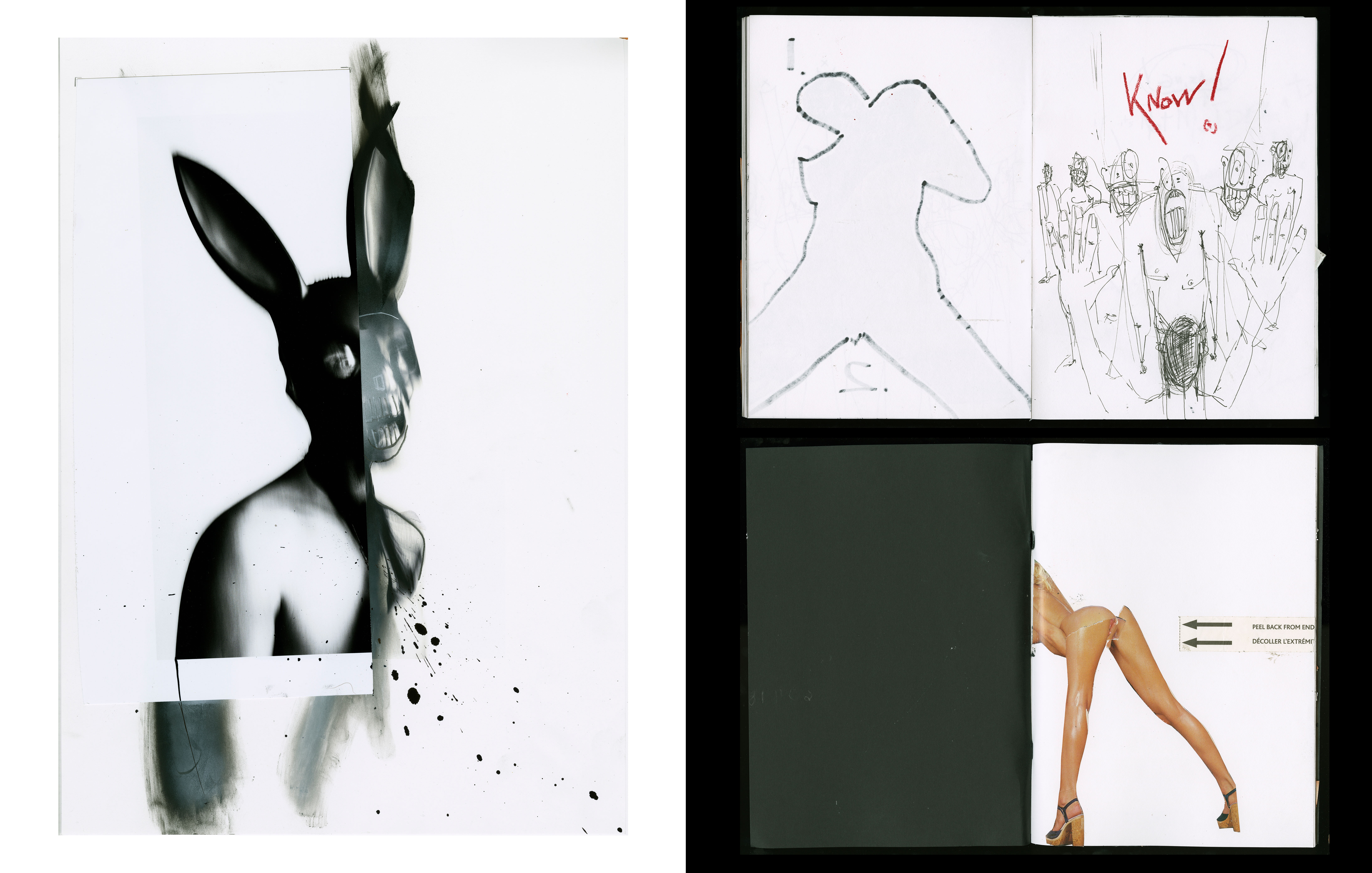

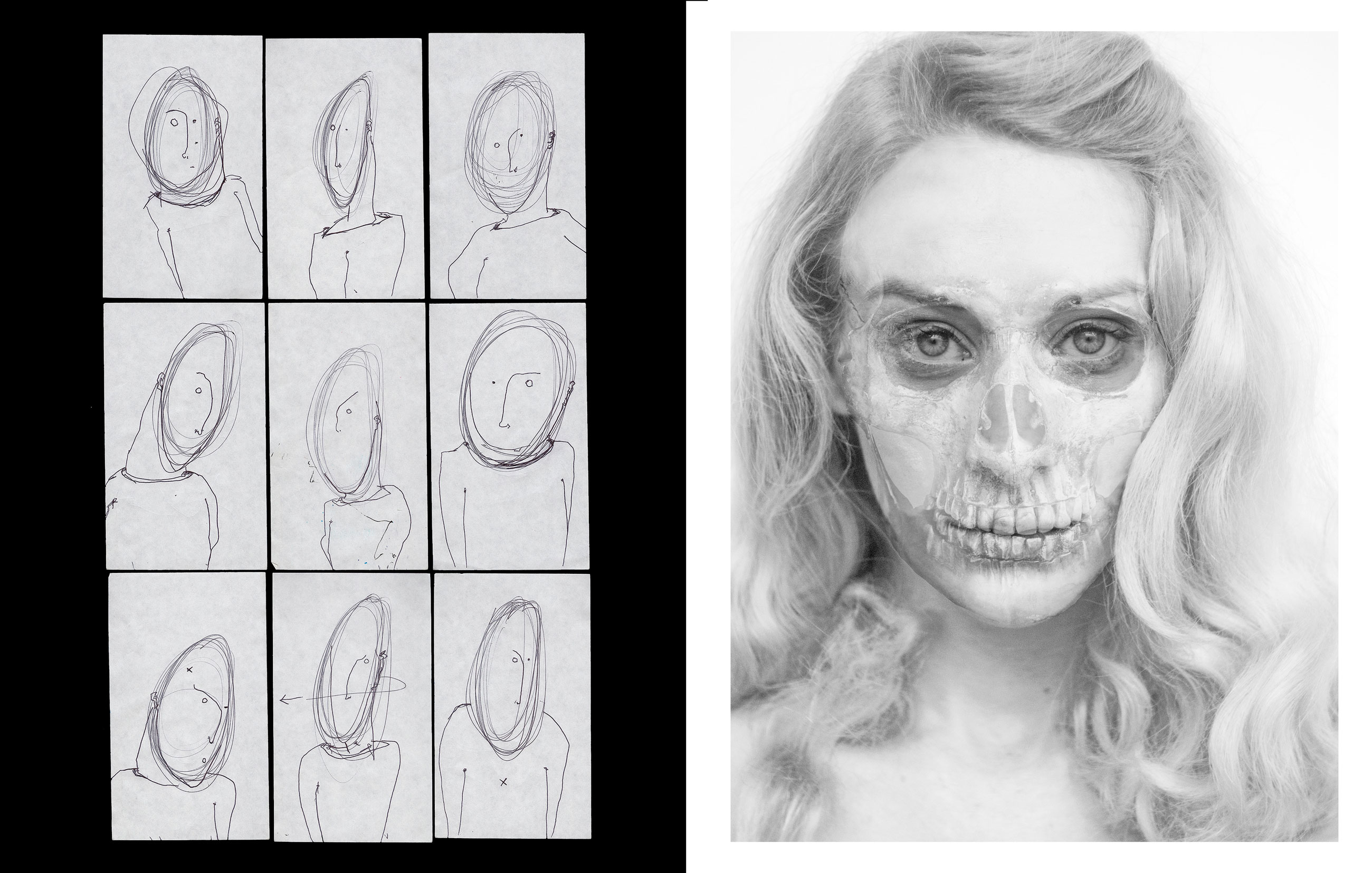

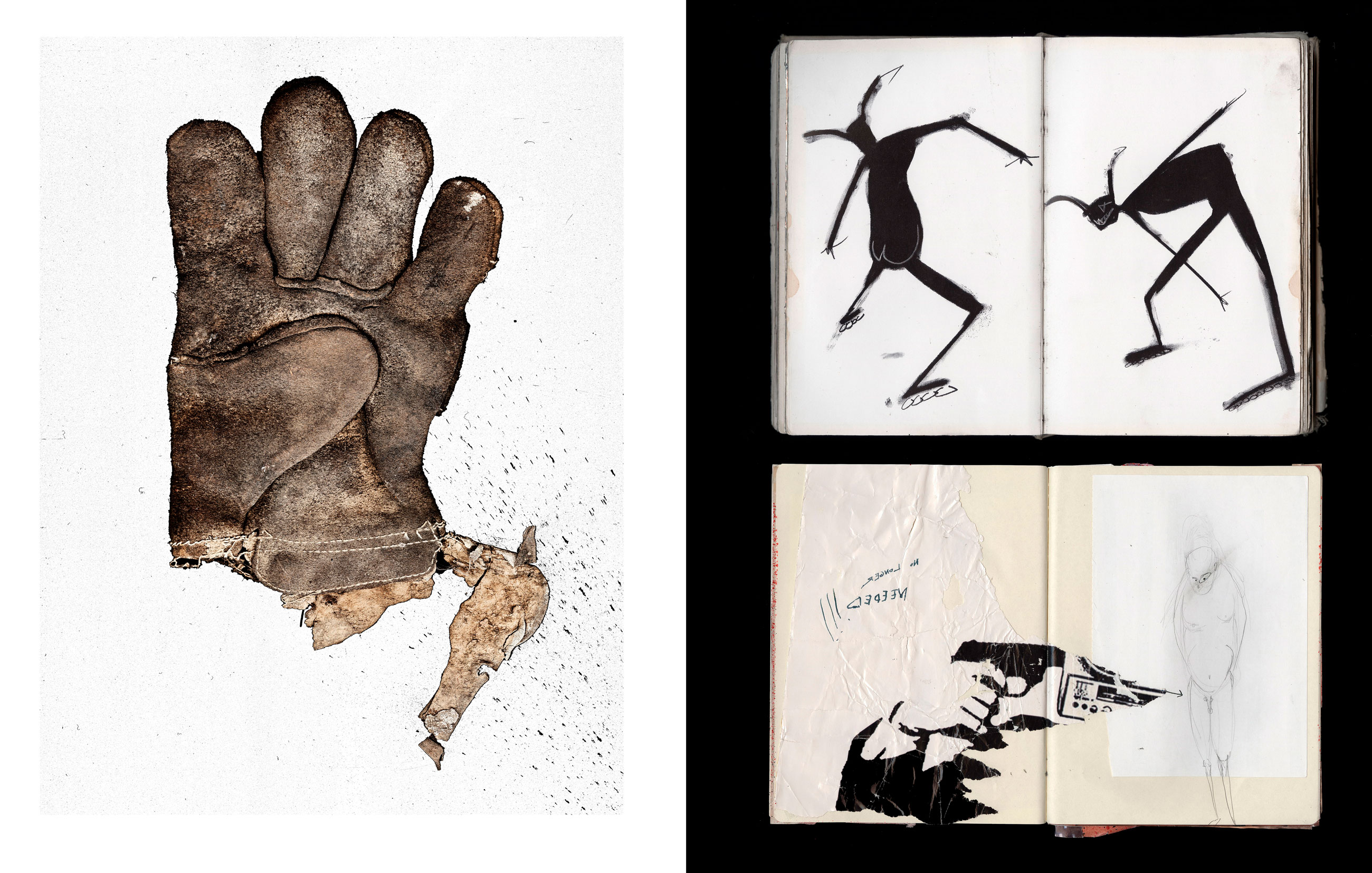

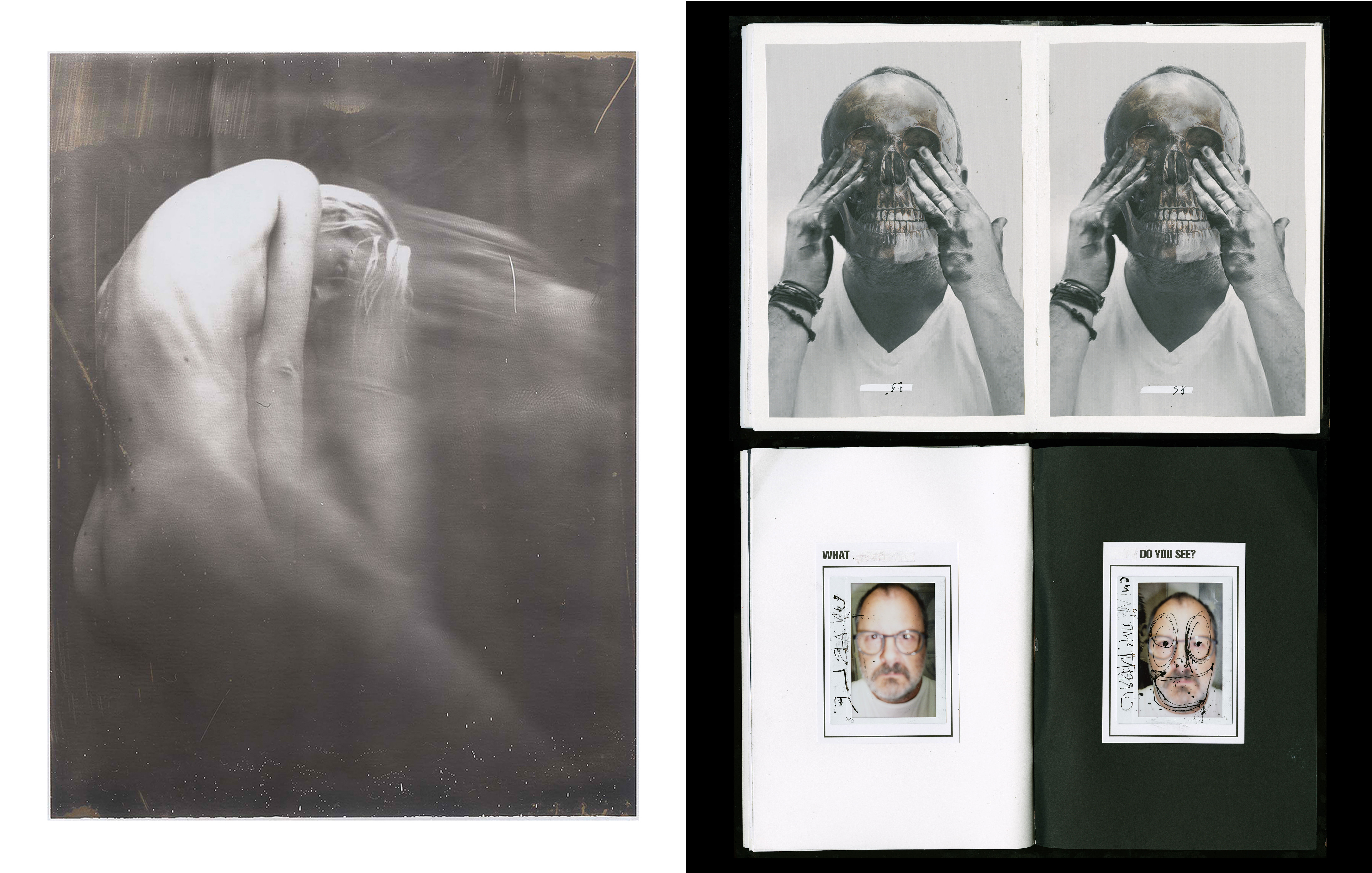

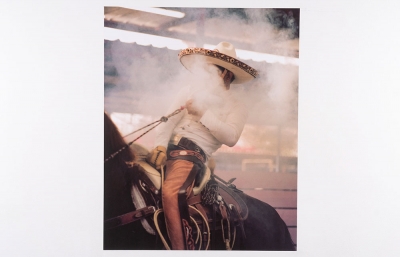

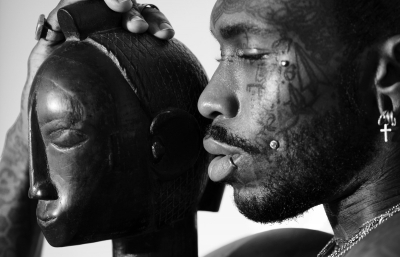

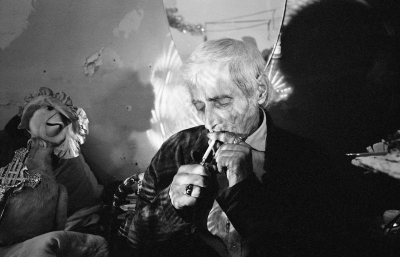

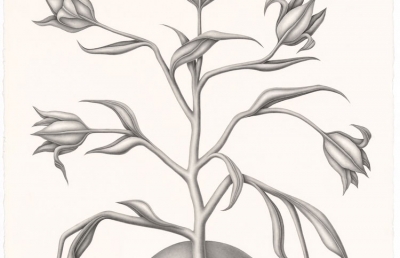

The work of Frank Ockenfels 3, published in his first book, Ockenfels 3, Volume 3, and on view in a new exhibition at Fahey/Klein Gallery, provides a window into the visual processes of the renowned photographer. Ockenfels, who began his career photographing for such magazines as Rolling Stone, Spin, Vanity Fair, and Vogue, is known for incorporating collage, painting, drawing, and other non-photographic elements in his works. His personal collaged journals, which are the focus of the book and exhibition, present a conversation between the artist, his work, and the world around him. Ahead of his exhibition, we spoke to Ockenfels about his journals, the importance of experimentation, and maintaining the element of surprise in a digital world.

Alex Nicholson: Is this your first book?

Frank Ockenfels: This is it. I’ve done some just for fun. I had an exhibition in Amsterdam and made a really simple book that was just a gist that the show. Years ago, I made a handmade one for the first exhibition I had but this was the first where a publishing company has stepped forward and been involved.

How long has the process taken?

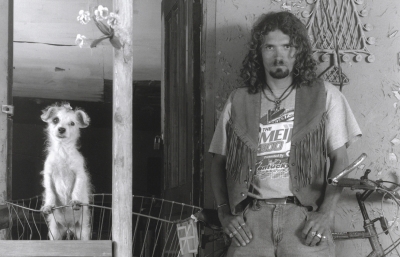

About a year, but it's a culmination of a lot of years or work. I usually scan my journals once a year to make sure I have a record so I had everything ready to go. The process was interesting in the sense that David Fahey and Nicholas Fahey called me from Fahey/Klein Gallery and asked if I had any interest in doing anything with all the stuff I had sitting around. I showed them four bodies of work, which was a little overwhelming because they were all over the place. There's a whole body of shoots I'd done over a nine year period with David Bowie, and then there was my journals, my drawings, and then these portraits I've done over the years with this one camera. I didn't know what they were going to come back with but they’d taken them all and put them together. I wouldn't even have thought of putting it together in that way so it was great.

Did how the book came together inform the exhibition?

It started the conversation. He laid out what eight pages would look like, how he saw things going together. After that I started going through everything and laying out pages based on how things fit together in my brain. I wanted the feeling of the book to be as if you're looking through my journals. It's not a typical book. I wanted to do something different and share my brain because I don't usually share my journals.

When did you start making journals?

Back in the '80s.

Did you make them thinking someday you would show them or was it primarily just to work out ideas?

The simple process started by me keeping these text journals, which were just lighting references so I could remember things back when we used to shoot Polaroids. Then it rolled into this thing I would do on airplanes. I’d cut up pieces of paper and put them into another journal and then write notes on it, ranting about how much I didn't like the shoot or something I had just experienced. You’ll notice a lot of the writing is backwards because I'm dyslexic. It was easier and quicker for me to write backwards and make sure that I had all the words there for myself just to know I put them out. It just made more sense to me. It wasn’t really meant to be read. I just wanted to mark time and ideas and feelings and put things together that kind of break up my brain. When I do the journals it inspires me to do other things.

Have you always been painting and drawing or did that also start with the journals?

It started more with the journals. I would sit on airplanes and take my scissors and glue out and put my pictures together and writing backwards on the plane as I was flying around. I probably looked insane. Nowadays I'd probably get arrested! I get really bored easily so I just started doodling and drawing little figures as I was flying around. Obviously, I was tremendously influenced by Ralph Steadman, his drawings and his observation of people, just the randomness of the scatter of the paint and ink. Over the years, it started going into the photography and all of a sudden overlapping where I would draw on the pictures more. I was connecting them that way to me, and that made more sense.

Then it started coming off the page. I started drawing on plywood or bigger pieces of paper and just trying it. I have to say, I haven't really achieved any kind of satisfaction with that yet. I mean, there's some things that are okay, but the journals make more sense. It's almost like vomiting. I'll sit there and do eight or nine of them and then I won't work on them for a week. Then I'll be walking past the table or something and start seeing how things kind of fall together.

Are there other painters and artists you're heavily influenced by?

Francis Bacon and Anselm Kiefer. When I started, Peter Beard’s journals were pretty influential in the sense of he did them without much of a structure. He just tossed stuff on the page. And then Dash Snow is a good one too because I liked how he would collect things and put them together. Sculpture is a huge thing to me in that the journeys of seeing a sculpture or looking at certain work like a Richard Serra and walking through his work and seeing how light passes and texture and the rust... I'm a big texture person. I like feeling things out. That was a big thing with the book, being able to feel like you can actually reach forward and touch something.

At what point did you start to try to bring those influences into your photography?

There's a bunch of us that started out together. Mark Seliger and I started out at the same time but we were very different in our approach and very different in what we wanted. I didn't want to be known for one kind of light or one kind of picture. I would constantly try to change and flush out ideas and change ideas. The act of doing that was important, the constant change, the struggle and the journey of trying to find how to do things differently. Sometimes I’d use broken glass or different darkroom techniques or weird old cameras that I'd buy at a flea market on a Sunday and shoot with on a Monday. I liked not really know what was going to happen.

I think the journals are a lot about that, where I don't always know when I open up the page what I'm going to put on it. That all started with that happening. At the beginning every photographer has to kind of copy somebody else. Back in my days William Coupon was the big photographer who shot everything against this one background. And there's Annie Leibovitz and all that too. It all made sense to me but at the same time none of it made sense. I couldn’t afford to do what Annie does and I don't have this and I don't have this, so what is it that I can do to basically get close to what that is?

When I was shooting music if they had 15 minutes with somebody, I was the one they sent. I used to laugh because I got into the rhythm of saying, "Well, I only have 15 minutes, and this is what I could do." If you have all day and you screw it up, it's a bigger conversation. So I started trying a lot of odd things, figuring, well, if you only give me a couple of minutes, if I try something really weird, that would make someone interested in maybe staying a little longer. That is how I started my relationship with David Bowie. I did something that had huge possibilities of failure. I knew that three other photographers were shooting that day and I knew their styles and I was like, "Well, if I'm last in the day, I might as well just throw care to the wind and see what happens."

As you’ve transitioned to digital, how has that changed? How do you still get that sense of “not knowing?”

There's so many things that can happen by the act of being innocent enough not to pay too much attention. Anyone who has ever watched me do anything on the computer, like Photoshop, shakes their head saying, "You know there's layers. You don't have to keep it. You can put layers in." And I say, "Yeah, but if you put layers into it, there's no commitment to it.” By the act of just doing, it is what it is.

And then from there, it's just the cameras. I go to this camera store in London, Mr CAD, and he has piles and piles of all this old analog photography equipment. You can buy old lenses for 20 or 30 bucks. No one wants them anymore because they don't auto-focus, they don't do this or that. Each one of those has such a personality that can cause flare or some kind of weird distortion. There's these things that happen that you can't do with a perfectly aligned digital lens. Recently my digital tech found some Korean surveillance camera lenses, and they were like 30 bucks. We bought a bunch of them and we found a way to put them on the camera.

How does having these unique cameras change the way people react to being photographed?

I shot for years with this handheld Super D Graflex, which has a big box you open up and you look down into, but it's a single lens reflex. Anytime I pulled that out, people would just look at me and go, "What's this about?" Then you pull the Polaroids and when they see it immediately, they get excited. Anytime you do something that's not normal in front of somebody with a camera they'll probably drop their guard. They'll see that it's weird or that it makes it more beautiful. It might just soften everything because the lens is a certain way. Knowing your subject is always a good thing to know how far do you want to push something.

How has photography changed you as a person, when you look back to before you started taking pictures?

I was the farthest thing from being the cool kid at school. I took pictures to interact with people. It became more of a conversation when they saw... which is the problem with anything in life. Sometimes people don't take people for who they are, they take them for what they do. But a huge part of my job nowadays is talking to people. I always make jokes. I call it being the cruise director because when you're doing the shoots that I do for a living, TV or movie advertising, you have a set and all these people and big actors that come in, you really have read the room quick and know how much you can say and what you can do and how fast you can move through things and make them feel comfortable and keep the conversation going. If you just stand there with the camera in your hand, and don't say a word, you're not going to get anything.

You teach a lot of workshops. Is there one piece of advice you continually stress to your students or advice you've held onto that someone has given you?

Anytime anyone walks up to you and wants you to take a picture and they say, "This is going to be really good for your career," you better understand that it's not going to be good for your career. It doesn't mean a thing, okay? No person who ever gets you to work for free will ever come back and hire you for the million dollar job.

I've done huge magazine spreads over the years or shot certain people. I did that. Now I track down musicians and find them cause I want to shoot them. I don't care what happens to the pictures afterwards, it doesn't mean anything. What I get out of it is a nice interaction with a young artist and to be part of their creative process, which I love. That's a piece of advice I would tell people. Do it because you want to do it. Don't do it because you think you're going to get something out of it. Know why you're being a photographer. If you're doing it for the money, there's a million other ways to make money. In anything in the creative industry, there's a small percentage of people that actually succeed at it. I have a lot of friends that are photographers that are 10 times better than I am and they're much purer in their vision because they get to do what they want to do every single day. If you're doing it because of the passion and not caring what anyone really thinks, good. But if you constantly are worried about are people going to like this picture? I mean, that's the joke about Instagram right now, right? It's the likes, you know?

It messes with your head.

I mean, it's all mental. It's all bullshit. If you like a picture and you post it, that's great because you love that picture. People will respond to that, and that's wonderful. Always know why you're there, what you're doing. It's hard even taking the pictures sometimes. You take a picture and somebody starts getting in your brain asking, "Well, what is this picture and why you're trying to do this?" Then you're stuck in some kind of weird whirlwind of trying to answer questions and you shouldn't be. You should just be moving through and trying to feel the moment out and taking a picture.

You've done a lot of motion and video work as well. How was that transition? Do you find that it was pretty similar process for you.

Lighting and framing and the photography aspect of it is very much the same to me. The other part of it, which was fun, was the collaging, the editing, knowing how things go together, what you want, how the pieces fit together, and why they go together. That's the cool part of it. It didn't make me want to do it for a living full time though, to be honest. Over the years I've been asked about directing movies and that kind of stuff, and it's just not in my brain right now. It might be one day, but I'm really loving being a photographer still. I still have a lot to learn. And as a photographer, I can change ideas every single day, and I can present people new ideas every single day. When you're doing motion, it takes forever to get something completely turned around to to be more than just an idea.

It involves a lot more people too.

A lot more, yeah. As a photographer, if I want to turn around to a beautiful piece of light that's coming in the window, I just do it. If you do that in a movie with a movie crew, you're suddenly righting the ship. The ship is suddenly turning hard and everyone is suddenly being thrown left or right, and you're responsible for that. I have no patience for that sometimes. I just want to do it and hand it out and say, "Look what I did," you know?

Ockenfels’ new hardcover monograph Frank Ockenfels 3: Volume 3 is available for purchase at Fahey/Klein Gallery or online at teNeues.