"Imagine you are walking along a field, a beautiful green pasture as far as your eye can see. As you walk along this pasture, you see a severed head resting perfectly in the golden sun. What's interesting here is the context of this situation: if this were an animal’s head, we would see it as natural - unfortunate for the poor creature, but natural nonetheless. We would assume it was prey for another animal, and this was simply its fate. A discovery such as this would not prevent most of us from moving on and continuing to take in the beauty of this gorgeous scene. However, if it were to be a human head we came upon, a sense of horror would strike us immediately. Countless questions would rush our thoughts; we would become repulsed by the sight of it. There are rules for us! That violence is unimaginable! Who (not what) could have done this? The sun-drenched pasture light changes; context alters this reality. I ask why? Aside from the obvious relatability of this poor soul, why must we assume we behave any differently than the savagery of nature?" —Jameson Green

Francisco Goya's The Third Of May, Pablo Picasso's Guernica, Diego Riviera's Pan American Unity mural, or Philip Guston's Gladiators, are some of the works in which the social and political injustice, human struggle, plight for freedom, and the eternal connection of life and death are portrayed through grandiose, often crowded and narrative rich scenes. And although some of those artists did address the racial or ethnic issues, we were anxious to see an artist adding a Black experience to this conversation. This is likely why we instantly fell in love with powerful theatrical paintings by Jameson Green, a graduate of CUNY Hunter College.

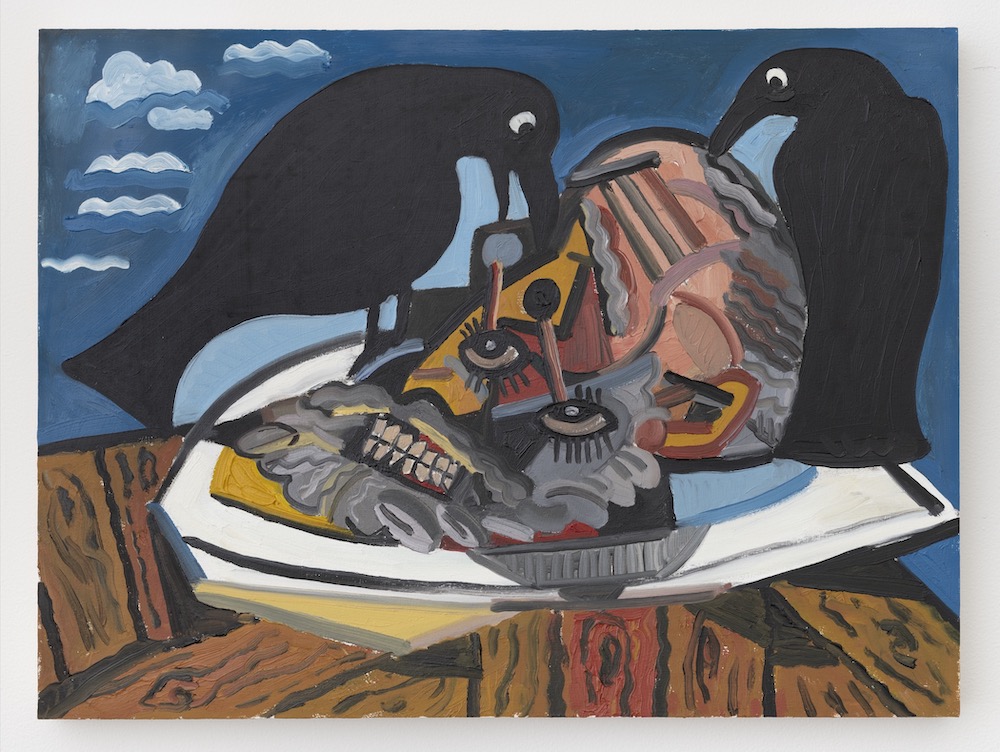

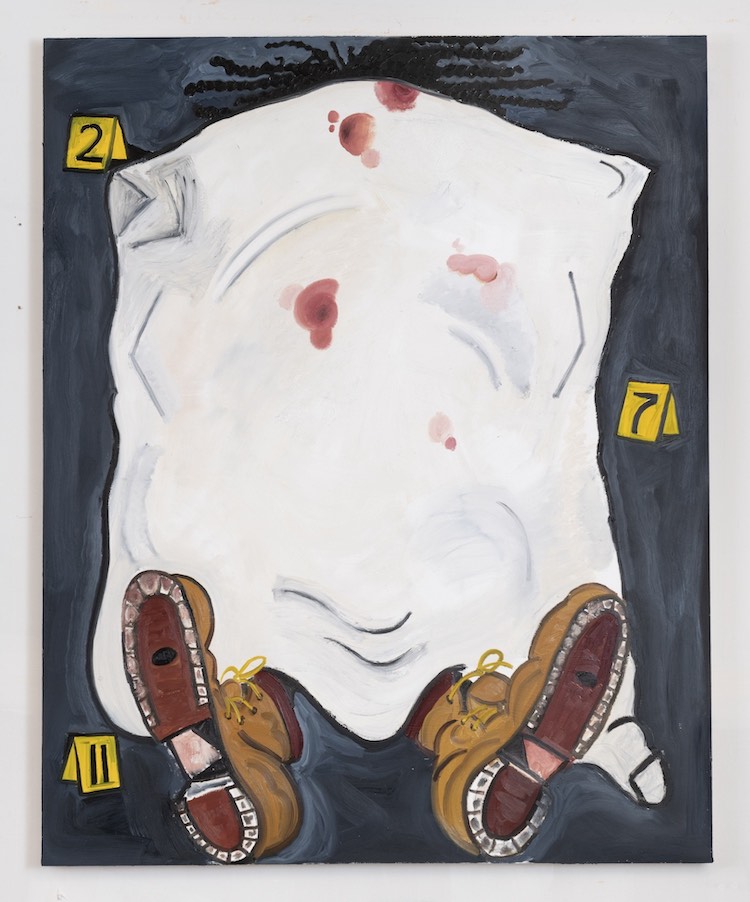

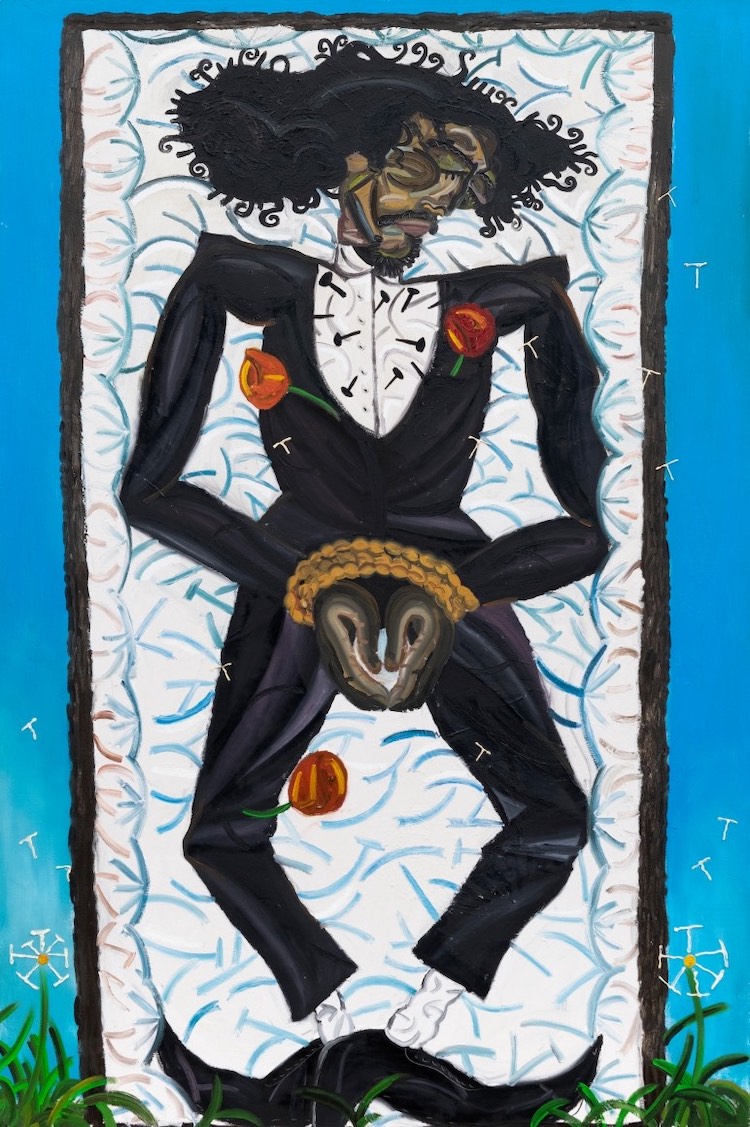

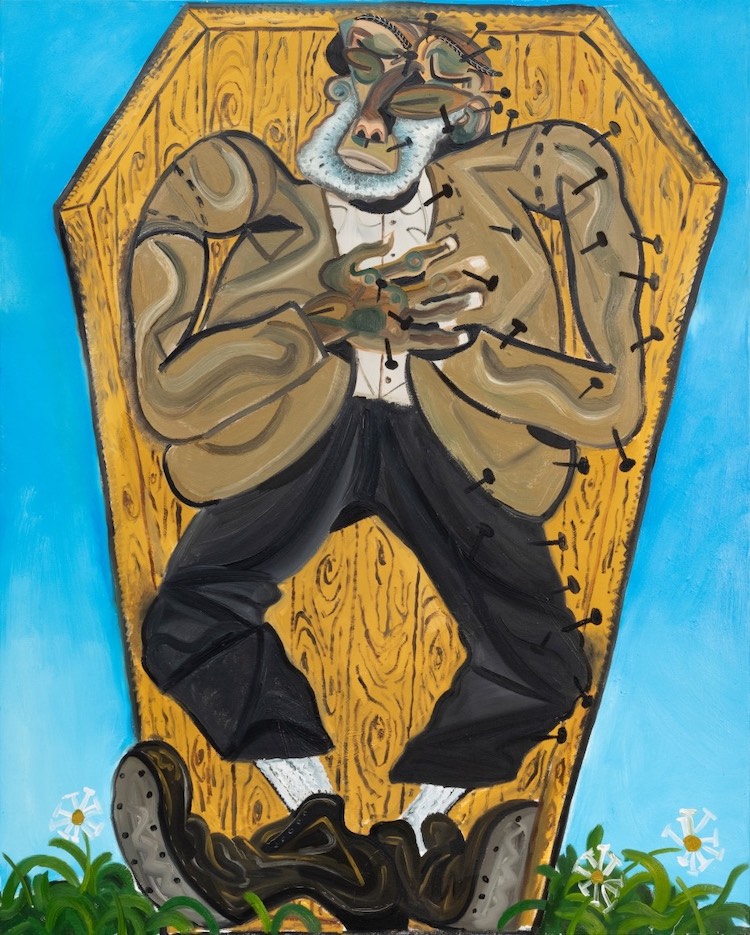

By mixing contemporary popular culture elements within cubist-like images rendered through a frenzy of determined strokes and gestures, Green is adding the long-overdue Black voice to this existential conversation. Often constructing narrative-rich scenes in which perspectives and scales shift to accentuate paramount elements, the Connecticut-born and Bronx-based artist is successfully mixing comic books storytelling with Cubism and/or Post Impressionism aesthetic and references to Catholic symbolism. "I really wrestle with the relationship between the grotesque and the sublime, and the beauty of tragedy," the artist told us about the captivating balance which permeates his paintings. "I use this scenario quite a bit to describe a key part of my work." By blending such striking and impactful elements when speaking of such duality he developed a weighty and convincing visual language through which he speaks of institutionalized racism and the violence throughout African American history. "The separation we have from ourselves and nature is fascinating to me," the artist told us about the philosophical source of inspiration behind his works. "We distance ourselves from the ugliness inside of us and in the world. It will ruin this beautiful life we have so we tell ourselves we are all good people and I say No. We are ugly monsters, capable of doing more damage to one another than good. We lie, we cheat, we steal, and we kill. Like every other living thing in this world, death threatens us. It’s the ugliness that makes us acknowledge the beauty and the precious things in our lives. You have to lose something to really know its value. I find the absurdity of that to be the most beautiful thing about life."

Using thick layers of vibrant hues and resolute black line work, it feels like every single mark is Green's physical response to an event or experience that perpetuates these unjust narratives. "I approach the difficulty of the subject using history as a tool, art history, American history, and my own personal history," he told us about the tools he is using to approach such monumental subjects. "The combination of these very much gives me the language and narratives needed to form a question that ultimately creates my work. The paintings I make are in search of an answer. What is that answer? I don't know yet and I'm not sure I will ever really know. But I have to ask."

The frequent references to art history are no accident as Green has a profoundly studious approach to assembling his images with nods to some of his favorites. "The influences feel endless, aside from the obvious ones people have come to notice like Guston and Picasso, I find myself fascinated with the powerful expressionism of Francis Newton Souza, or enthralled with the strong strokes and compositional fluidity of one of my childhood favorites J.C Leyendecker," he elaborated some of his favorite painters and particular works he's been recently looking at. "I know for my open casket pieces I was very much inspired by the Emmett Till Painting done by Dana Schutz. I'm In love with her work and I believed, despite contrary belief, the piece was an incredibly bold and powerful painting. The power and atmosphere of the Jacob Lawrence migration series will always be in my heart and echo in my work. I've responded deeply to the history of folk art and the strong narrative edge and cynicism of Max Beckmann, or much of the german expressionist for that matter. I love the drama of baroque art, Rubens' powerful twist, and turns of flesh or Caravaggio's intensity of theatre and light! I can be at this all day listing artists who I have a conversation with regularly in my studio." And although clearly using an alphabet of recurring, often recycled elements such as nails, shoes, KKK hoods, caskets, crows, Green is determined not to explain the particular idea behind each of them and allow for their nuanced meaning to come to life. Finally, it's this nuance that permeates the entire body of work as the explicit evil gets intensively cartoonized, and the scenes of exposed corpses, hanging bodies and heads, or body buried in a sofa evokes the gruesome cartoons before unfolding themselves as punchy depictions of life and death with an accent on African American history. —Sasha Bogojev