We keep saying this, but there are a ton of great painting shows to check out at the moment. Add Ellen Birkenblit's new show at Susanne Vielmetter to your list, a series bold and graphic paintings that have tempting and revealing depictions of everyday life and actions.

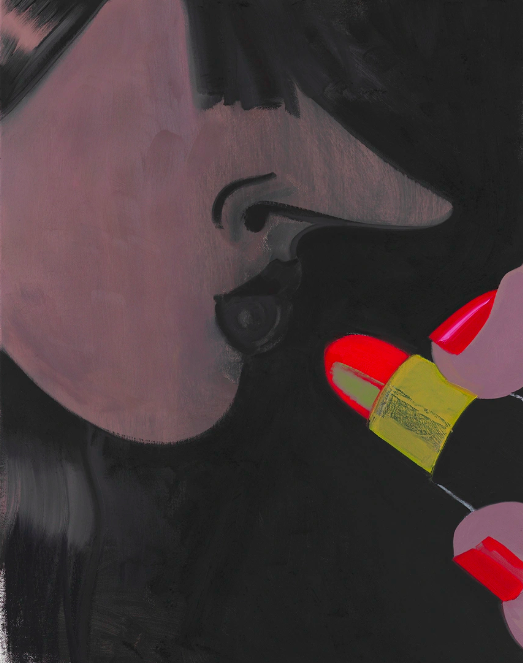

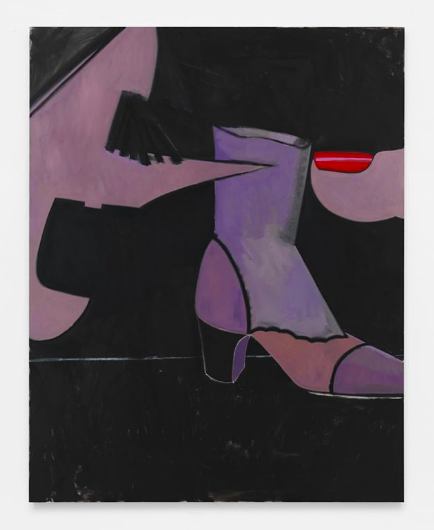

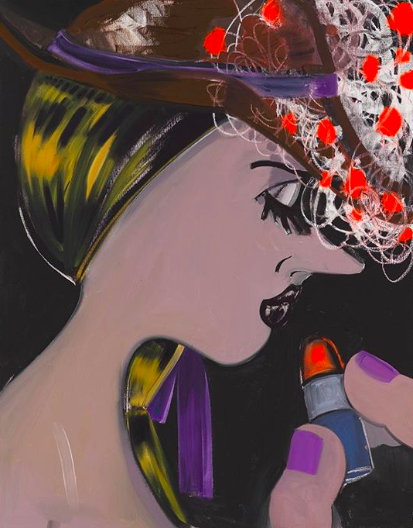

From the gallery: Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects is thrilled to announce the opening of our second exhibition of new work by New York-based artist Ellen Berkenblit. Berkenblit is known for her bold graphic paintings, defined by an ever-evolving pictorial calligraphy that includes a long-nosed woman in profile (sometimes a witch, sometimes a youthful beauty), a rather tame tiger, little birds, high-heels, five-petaled flowers, lipstick tubes, a manicured hand, etc. While these forms are suggestive in their familiarity and often associated with a classical notion of femininity, Berkenblit deploys them as intuitive reflections of her physical experience of the world, filtered through her body and emerging in composition: in Berkenblit’s paintings, these figures are transformed into abstractions – shape, line, color, direction, scale, orientation, texture, value—interacting within the boundaries of the canvas.

This exhibition of new paintings includes works on canvas in addition to works on patterned “quilts” of calico fabric. Berkenblit’s use of patterned calico parallels her use of paint—she stitches the calico together, considering the relationships between color and pattern, a sort of puzzle of compliments and contradictions. Then the joined fabric is sent out to be stretched, after which it returns to the studio as a familiar, but unfamiliar problem to solve, this time through painting. Like the images that compose her visual language, Berkenblit tries to let these relationships, between fabrics and paint and pattern, reflect a sub-conscious yet active transformation through her intervention. The inclusion of sweet floral patterns and domestic ticking stripes draws additional attention to the assumptions that one may make about the forms that populate the work. Female bodies, trucks, traffic lights, shoes, flowers, lipsticks, a manicured hand—all are rather mundane images that might appear in a casual doodle along the side of a young person’s class notes. In Berkenblit’s hand they undergo a certain alchemy, she doesn’t entirely drain them of their content and associations, but their logic becomes the logic of dreams and of the body. These shapes repeat through a gestural, physical expression: reach of the artist’s arm, the flick of her wrist. They are fleshed out through her interest in how mauve and lime green play together, in how many colors compose a velvet black vs. a polychrome lipstick tube. This constant returning to the abstraction of the very familiar suggests a path to unlocking the suggestions inherent in the forms Berkenblit repeats, why our minds insist that these particular shapes must narrate femininity, desire, and innocence so automatically.