Why do we even bother to look at art in this day and age? Is it for the hope of a deeper exchange or some promising sign, if not of a better life, of a finer, more dear appreciation of this one. In The Drift at Dolby Chadwick Gallery, Terry Powers reminds us that art can still function as a form of gratitude for the affirmative act of turning pigment into poetry.

In a painting by Terry Powers, one may see: a spade, a wind-up doll, a broom, a teapot, a ball. One may also read a brief diary of the moment or dated meditation beneath or across the scene. Behold the private history of a man and his days. For us, the viewer, what do we gain from this intimate gaze? What is the world into which Powers lures us to peek, as though through an open window or a gap in the garden fence?

The English art critic, novelist, and painter John Berger once wrote: “It seems to me one looks at paintings hoping to find some secret. A secret not about art, but about life.” If this is so, what key does the brush of Terry Powers allow us to unlock?

Powers’ paintings reflect the modern life of a young family in Northern California in the third millennium; yet, their roots lie in the Northern European Renaissance of the 1400s, which brought art down to earth. In rebellion against the lofty ideals of the Roman Catholic Church, rarified constructs of truth & beauty became everyday affairs in the hands of innovators like Jan van Eyck, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Hieronymus Bosch. Protestant theology and the rise of a new merchant class opened common scenes and subjects to the scrutiny of depiction and the insights of allegory.

In this vein, one can see Powers’ strewn-about toys and tools as casual but potent symbols. Each painting illustrates a parable of sorts. The running commentary that captions most pieces provide a clue as to how one might read the artist’s state of mind. None of this is to suggest a didactic intention in these subtle, unpretentious, and utterly lovely vignettes. These paintings do not lecture, they offer you a chair, a cup of coffee and a wonderful conversation about the meaning of life or that thing that happened on the way to the store. They are vital, they are real, and they are necessary in the way that friendship is. They are the subtlest form of treasure.

The poem “Angel Surrounded by Paysans” by Wallace Stevens conjures one of his best-known lines and images: the necessary angel. Stevens was a collector of modern art and his poems often played with the rival views of surrealism and abstraction. This particular poem describes a still life painting by Tal Coat. Stevens singles out a Venetian glass bowl as the embodiment of human imagination and assigns the role of paysans or peasants to the terrines, bottles, and glasses that surround the bowl. In a later essay, Stevens wrote that the point of the poem was to suggest that there must be things in the world around us that comfort us, just as much as a celestial visitation might.

Yet I am the necessary angel of earth

Since, in my sight, you see the earth again

Let us look more closely now “in the sight” of Terry Powers. The 13 paintings and 12 works on paper that comprise his current show The Drift at Dolby Chadwick Gallery were painted in 2020 and 2021, during what we might call covid times. The oil on paper pieces are titled by date and contain the most written narrative. They reflect days in which monotony and anxiety are commingled.

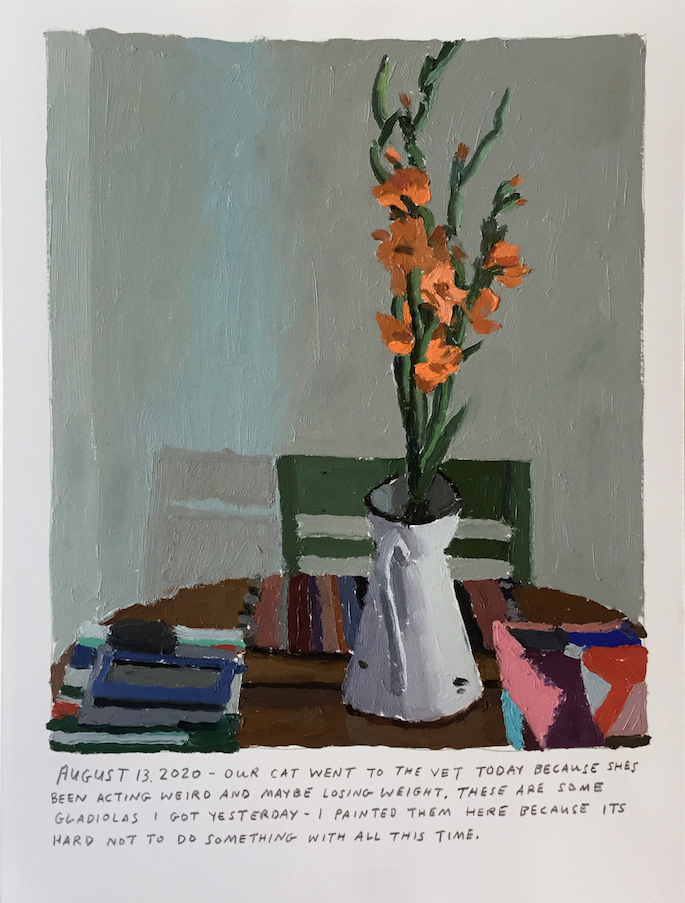

August 20, 2021 captures a loose depiction of a table top, place mats, chair back, and a chipped enamel vase holding sunny gladiolas. In block letters beneath is the explanation: “Our cat went to the vet today because she’d been acting weird and maybe losing weight. These are some gladiolas I got yesterday. I painted them here because it's hard not to do something with all this time.” These seemingly simple lines communicate so much about agency, or lack thereof, and the desire to assert some order over a day full of unanswered questions.

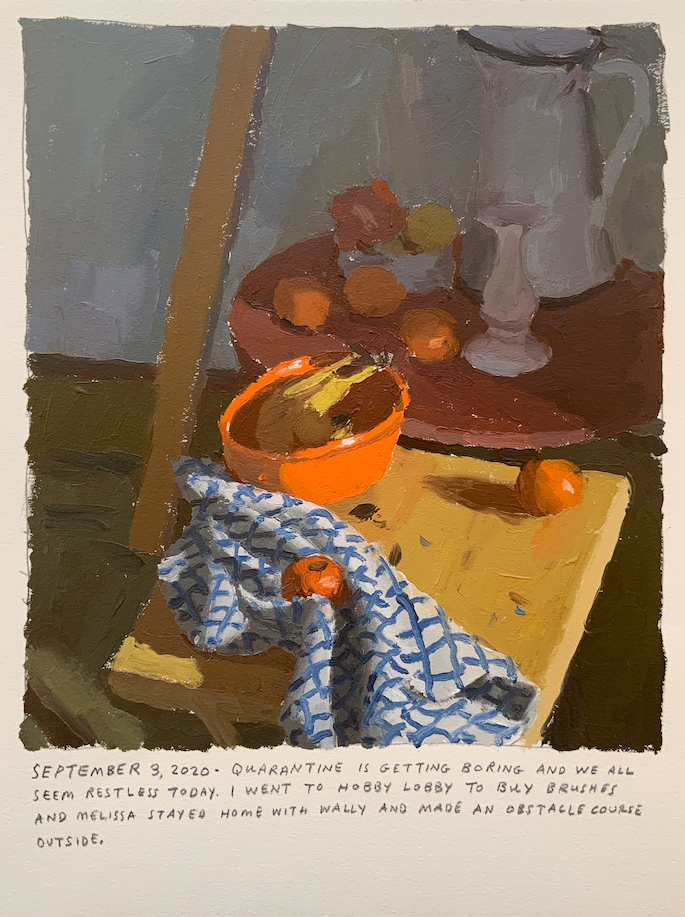

There is something profoundly affecting about the conversation between text and visual happening in this work. September 3, 2021 is another wonderfullly loose still life of honied wood tones, warm white, bright oranges, and a complementary blue checked cloth. The text notes the restlessness and boredom of quarantine. Line two casually mentions a trip to Hobby Lobby for brushes, but one can’t help think of the controversy surrounding the company’s evangelical founders (homophobia, anti-semitism, vocal pro-Trumpism, illegal smuggling of biblical artifacts, and endangering employees during the pandemic). The sentence ends by noting that Powers’ wife Melissa and son Wally “made an obstacle course outside.”

Text for Powers is an additional tool, but the paintings speak volumes even without. Our Time, 2021 places a skull and spade amid rubber balls, a plastic bat, and scooter. The joys of youth are thus directly juxtaposed or conjoined with props from the gravediggers scene in Hamlet. A similar provocative pairing occurs in the large painting Blood Pressure, 2021, a gorgeously rendered white sheet is strewn with typical still life objects (cups, plates, vases, flowers) and a machine for measuring blood pressure (high blood pressure is still the world’s leading cause of death for adults and children).

The refinement of brush work in the larger paintings is also interesting to consider against the quicker more gestural work on paper. It not only shows Powers’ range, but invites consideration of the question as to whether a still life must be technically accurate to be interesting. It is often the quirks and choices (in subject, angle of rendering, mark-making, mode of restraint or indulgence) that open new vistas. In Powers’ case, textural elements act as points of departure for deeper engagement with the artist’s imagination.

A still life may be deliberately posed or circumstantially captured. It can indicate order or disorder, calm or drama, yet it’s essence remains domestic. A still life is a lesson in intimacy. The objects themselves jostle for space, lean into or upon one another, or hold their own ground. The viewer is offered a glimpse into the private world of the artist’s community. With Powers, placements come to feel as inevitable as gravity. There is an easy patois between the shapes, textures, colors, and levels of radiance. They are tangible even as they play their metaphorical roles.

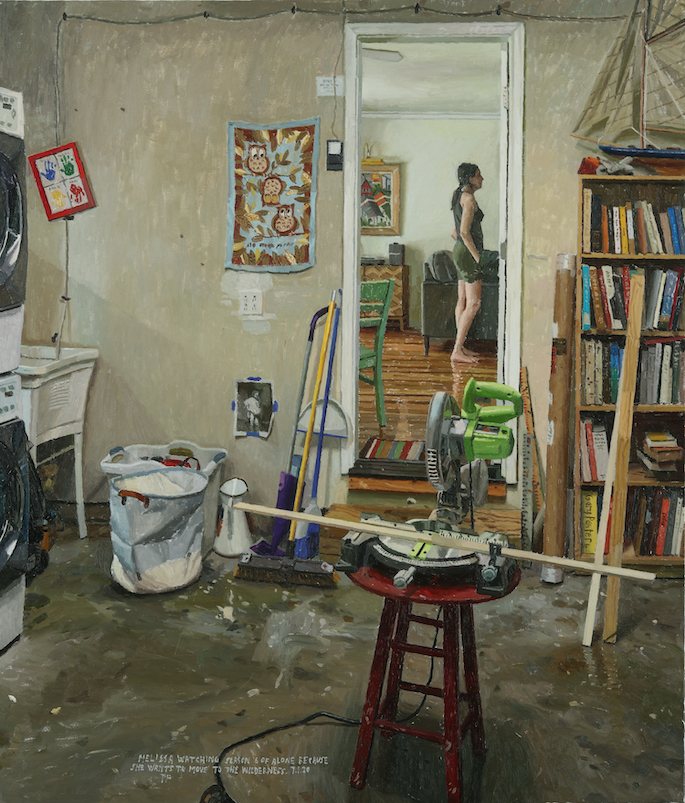

When Powers adds a figure, it is that of his wife. Her corporeal presence extends this sense of the fundamental interrelatedness of existence. People move through the world, brush up against or stand near other things, alter and become altered. The scenes imply such a narrative, sometimes deeped by the painting’s title. Two large and eloquent paintings Our New Comforter Doesn’t Fit the Old Bed, 2021 and Melissa Watching Scene Six of Alone Because She Wants to Move to the Wilderness, 2021 reinforce the relevance of even the most seemingly inconsequential detail. They are profoundly provocative not despite but because of the humble moments and items they capture.

The show’s press release notes that Powers was influenced by Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. This was, of course, the painting that inspired W.H. Auden to write that even amidst scenes of “dreadful martyrdom” or “a miraculous birth”, the Old Masters knew children would continue to play, dogs would do what dogs do, and “the torture’s horse / scratches its innocent behind on a tree”. The artist, like the poem’s ploughman, may “hear the splash” of Icarus but “still has somewhere to get to and sails calmly on”. Powers likely wouldn’t consider himself sailing calmly on, but through his art, he propels himself and his viewer forward to embrace the human position in a world of joys and sufferings, both small and large. —Tamsin Smith