Letter to Myself (when the world is on fire), on view through February 25th, is a joyous panacea for contemporary woes.

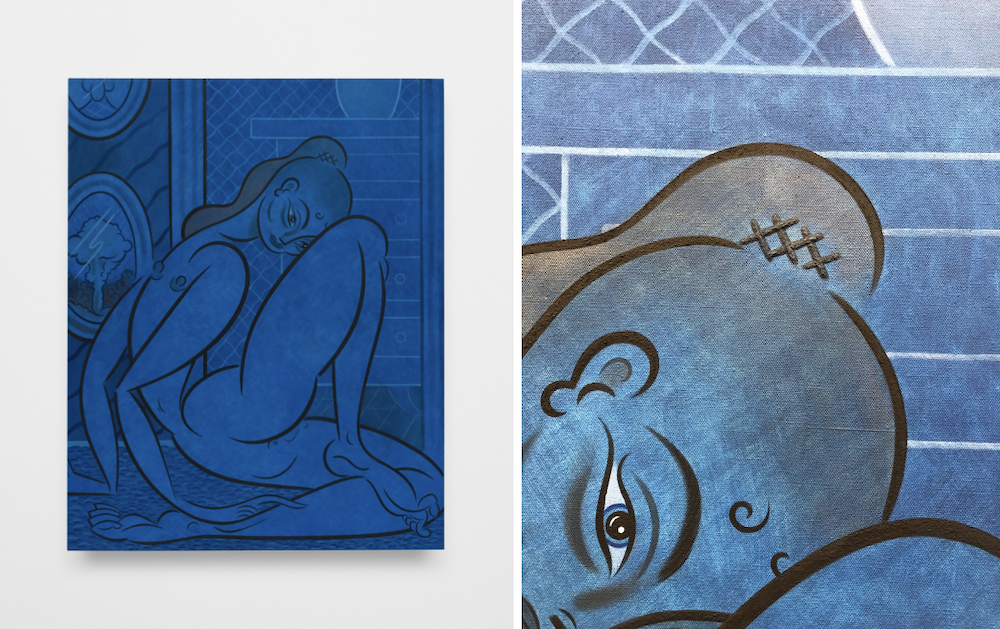

Prehensile toes and wiggly nipples are littered throughout the artist Koak’s second solo exhibition at Altman Siegel. Spawning from the artist’s musings on overexposure to constant, casual-ized disaster, the show infuses levity and humor into doomy scenes. Koak’s tender figures, bodies at once delicate and bulging, and confident and precise linework are at their height in her most recent show.

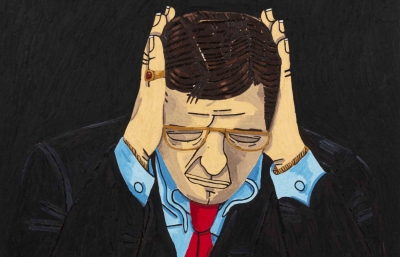

As the title suggests, the show serves as Koak’s letter to herself, a sort of time capsule of images and emotions emblematic of the modern moment. The artist remarks, “We get our news interspersed with kitten videos and go from California fires to California sunsets in the span of minutes. The line between danger and safety, calamity and calm, feels unmitigated—we move too quickly between the two to remember when to laugh or how to cry.” In this exhibition, Koak is able to bring levity to these cyclical spurts of hyperactive worry and sedation.

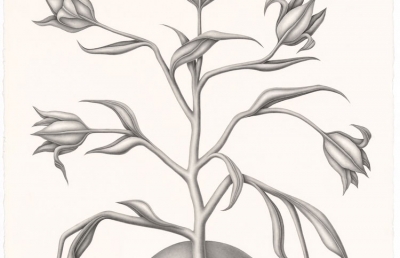

A vein of tenderness and fragility courses through Koak’s new paintings. Images of drowning tulips and women craned over to examine their genitalia pull the viewer’s focus. A cracking vase comes up in a couple of works; in Self Portrait w/ Flowers the artist paints her own likeness upon the fractured ceramic. There is a feeling of imminence, a sense of solidity that is just about to burst. The vase, like many of us, is barely holding it together.

Imagery that could, in other circumstances, come across trite (as the imminent destruction of the world can unfortunately seem), is reinvigorated by Koak with vibrancy and coyness. In Doomscroll we find such an instance, in which two images line the wall to the left of the primary figure. The lower frame holds a mushroom cloud, an explosion in an otherwise edenic environment, and the upper one depicts cartoonified male genitalia. These images, a hilarious one-two punch, are washed over in the blue of the painting as the figure examines her own body with an empty stare, caresses her calf, ignoring the eye-catching features behind her. The paintings on the wall seem like memories she has fixated upon, formative traumas in her past that now float around her mind like nothing. She is emblematic of many of us, numb to shock, “doomscrolling.”

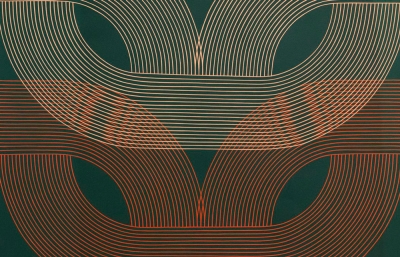

The focal triptych of the exhibition fills an entire gallery wall, each painting an expanse of biblical importance. The three scenes portray three windows lining a single external facade of a house. According to the gallery’s press release, these paintings can be seen to represent, in sequence, “inquisition, awe, and fear.”

Promenade is perhaps the only painting in the show that gives a sense of franticness. There is an outward energy rather than an introspection that drives the work as the bird loses feathers in the wind and flesh colored nipples blow in the breeze. In the nest of eggs at the right of the canvas, we find an image of birth and the inquisition that comes with youth.

In Facade, a figure having just awoken greets the yellow day, peering out from drapes dotted with phallic floral shapes. A fire burns below, but the shadow on the figure’s neck comes from a downwardly-shining light source, the implication of sun. The light from the fire is intentionally eschewed in the rendering of this image, absent from the eyes, casting no shadow. The figure displays ambivalence as her hand droops to point toward the hell below. What may have once been “awe” is only an echo of such a feeling. We see here observance without reaction, acknowledgement with feigned sympathy. As Koak states, “everything starts to feel like a mix of amplified emotion with the catatonic state of burnout blasé.”

In En Garde, the figure grasps the bars of a window like a cross repelling a vampiric force. Around this fiery interior, the scene is entirely pleasant — colonial moldings around a window wooded in by peonies suggest a quaint neighborhood environment. The crimson figure and drapes feel fiery, in contrast to Facade where the fire burns outdoors. This creates a sort of “the call is coming from inside the house” tonality underlining the scene, an apt metaphor for our current climate situation, or really, our current everything situation.

Koak also flirts with texture in many of the new works. Her flat washes of color are deceptive in creating a 2D feel, but much of the linework actually protrudes from the surface. In these elevated strokes, there is a sandy sediment visible in the pigment, allowing gestures with different weights to fade into the canvas or emerge out of it. It is fascinating to observe Koak’s smooth, driving lines up close and find this unexpected crunchiness.

Perhaps one of the most grabbing paintings in the room is California Landscape #1. The imagery is intense and full of motion, but it is Koak’s use of charcoal from the California fires to create the underpainting sketch for this work that yields such a powerful piece. Here, she physically achieves what she seeks to do metaphorically — disaster coated in beauty, heaviness layered with levity.

She lays pigment over natural elements, thus creating a palimpsest of color and dynamism over destruction. It is a cacophony of hues both natural and supernatural: a sea foam green sun, a blue Seussian tree dissolving into flames, pinks and magentas abstracting the inky smoke. Koak's foray into the landscape is a potent reminder of the toxic sublime. In the same way a beautiful sunset reminds one of the pollution required to create it, we are sucked in by the burning horizon, staring wide-eyed and numb.

Koak’s “letter to herself” beautifully juxtaposes the internal and external aspects of modernity; the sensory and emotional aspects of existing as a human being and the unfortunate humor of being subsumed by never-ending panic. The paintings are stunning concoctions of color and texture, lightness and darkness, laughing and crying. Koak’s freaky figures are a joy to behold.

Text by Annie Dauber