David Ligare makes paintings about ideas. He accomplishes this by rendering scenes with great technical skill from stories that are grounded in classical mythology which now comprise many of Western culture’s foundational texts. At a time when contemporary artists eschew historical narrative painting; preferring conceptual art, abstraction, or traditional realism, Ligare’s paintings may seem anachronistic in comparison. But many such critics would be surprised to learn how he came to his subject matter. It was precisely the innovator's impulse to do something that wasn’t being done by others that led him to this style of painting. Over forty years later, Ligare continues to mine rich historical narratives that offer ways of processing contemporary ethical challenges and infusing meaning into our complex lives.

Ligare’s work poses the question of whether paintings can lead to rational discourse within the context of ideas and history that have grounded Western thought. His brand of humanism promotes agency and choice. It explores narratives that, though singular, actually speak to shared experiences and cultural values which are uncovered by engaging in moral and philosophical inquiry. Rooted in Western myths, he traverses themes which cross cultural and national boundaries, and presents moral lessons that are shared archetypes originating within distinct cultures, though his work focuses on Greco-Roman traditions. Ligare’s paintings, aside from being beautifully rendered, are aspirational. In today’s environment of political polarization and misleading social media assertions his work inspires a quest for knowledge and the associated ideas that emanate from truthful inquiry.

Arete, Excellence and Moral Virtue

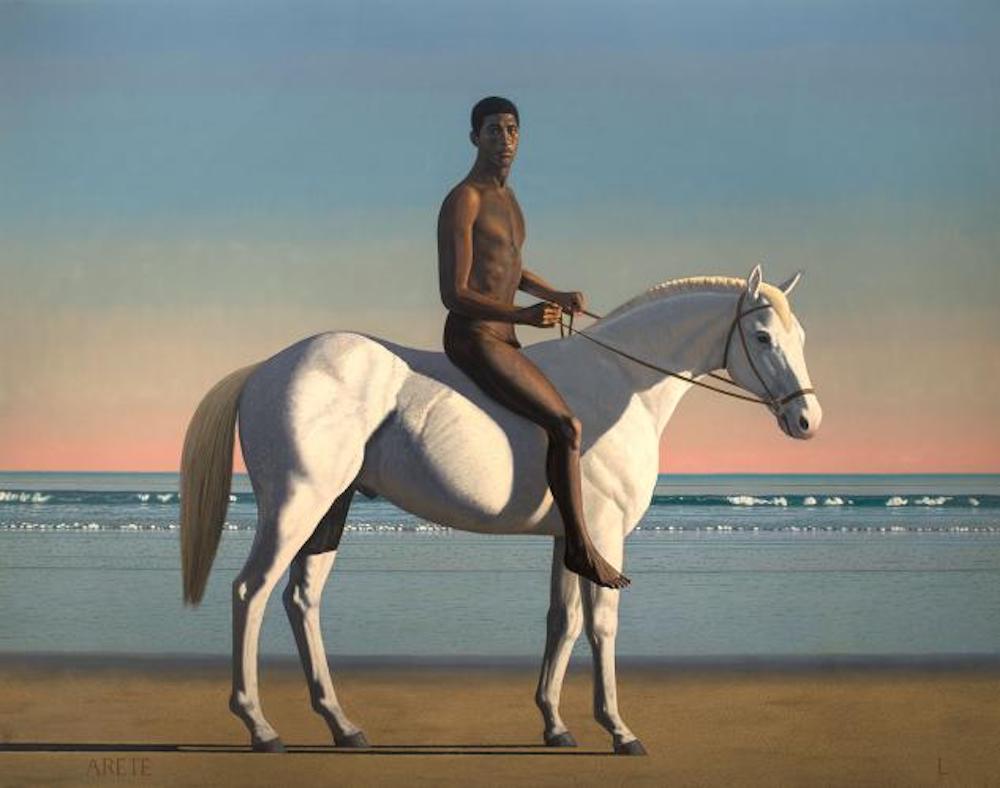

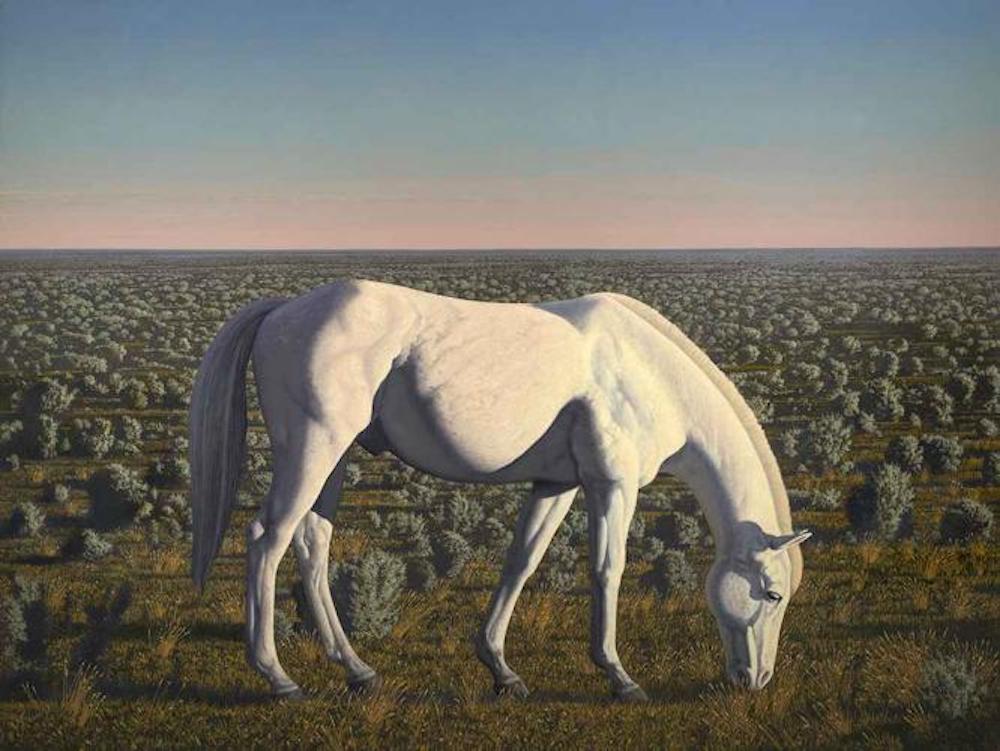

Ligare’s current exhibition at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico Presence of the Past, includes sixteen paintings primarily from the last two years comprising still-life, landscape, and figural paintings evocative of foundational cultural beliefs. The most conspicuous and dramatic painting, the largest in the show titled “Arete II” (oil on canvas, 72 x 94 inches, 2021), depicts a black man on a white horse, set against the backdrop of a beach; at first glance it seems to be simply what it depicts visually. But it’s title Arete, references an idea in ancient Greece, referring to excellence and, in effect, moral virtue. The concept conjures up the desire to fulfill purpose and to achieve the most; in effect, to live your best life. Painted in the wake of the George Floyd killing and Black Lives Matter movement, one can’t help but make an association.

Ligare has cited the work of Elaine Scarry, “On Beauty and Being Just,” when discussing his work. She posits that beauty moves us toward a greater concern and understanding of fairness, in effect, that beauty is justice or a value that leans heavily toward it. Depictions of beauty in paintings and objects convey fairness and justice because of their impact on our sensory perceptions; we can feel their sense of completion and integrity. For Ligare, depictions of beauty visually challenge us to satisfy greater civic obligations and inspire personal growth, although this sentiment isn’t about arrogance or narcissism. Like his own brand of representation, it isn’t perfection that he’s pursuing, but rather how the common man and woman acquire exalted status as they play out their lives in dramas that will later be codified as myths. Here, Ligare is telling us this black man embodies excellence (Arete); we merely need to confront our own biases; which curiously are conjured up the moment most of us see the markedly contrasted black man on a white horse. That we find the subject matter arresting or unexpected, itself raises issues of who we believe can attain Arete. A discerning viewer gazing upon this painting will contemplate what it is to be human and how ideas of excellence are realized regardless of culture and geographic boundaries.

Ligare’s first painting concentrating on this theme (Arete) was painted over twenty years ago (now in the collection of the San Jose Museum of Art), presaging societal reckoning with race transpiring in our country now. His engagement with the subject raises all kinds of questions, not the least of which is what does it mean for a Caucasian painter to depict a Black man; and how do contemporary historical moments constrain our opinion of that? That Ligare is celebrating, while also recognizing the beauty of the other, may be a sufficient answer. The painting draws attention to the historical fact that blacks have been largely left out of our most prominent cultural institutions. He reminds us that “Classicism was an amalgam of styles and ideas from the earliest and smokiest of times. It absorbed something from all of the cultures that it came into contact with, from Egypt and Africa to Asia, creating in the process an enormously inclusive rather than exclusive ideal.” Why then should an audience self-limit its visual expectations?

Interestingly, the ancient Greeks had a robust tradition of black-figure pottery painting on their vases that depict many of the known mythological narratives Ligare illustrates. Ancient Athenian potters applied a slip that turned black during firing, and which was later augmented with other colors and incisions. The black figures look like silhouettes and although illustrate Hellenistic scenes, by the 4th century BCE it was common to depict the black African peoples the Greeks called Ethiopians (Aethiopians), who inhabited the region across the Mediterranean Sea in the geographic area extending from the upper Nile to parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. Ligare’s advancement of excellence and virtue are exemplified in art historian J.J. Pollitt’s description of Arete as “the innate excellence of noble natures which gives them proficiency and pride in their human endeavors but humility before the gods.” That Ligare has returned to this composition tells us he believes this is a message which bears repeating.

Sidney Tillim & The Resurgence of Narrative Painting

Ligare first embarked on his mature artistic style in the late 1970s, when he joined a small, yet courageous, group of artists who revived narrative painting during a time when Pop, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art were at their height. An essay by painter and critic Sidney Tillim, “Notes on Narrative and History Painting,” in Artforum in 1977, wherein he made the case for “purposeful representation,” solidified Ligare’s decision to pursue what was then considered a played-out and antiquated style. Ligare had first seen one of Tillim’s paintings at the Whitney Annual five years earlier; Ligare recalls “It was a crudely painted picture of American Colonial-period figures in a landscape,” titled “Count Zinzendorf Spared by the Indians.” He found it to be strikingly original. Contemporary artists weren’t painting stories, not in any concerted manner, and certainly not of a historical theme. A few years earlier, Alfred Leslie had made a series of paintings, “The Killing Cycle,” influenced by various calamities in his life including the death of his friend, poet Frank O’Hara; but they weren’t exactly the historical emphasis Ligare would pursue. Ligare was less interested in personal contemporary subject matter and found the allure of illustrating foundational philosophical ideas to have greater resonance.

Tillum would variously reengage with an abstract expressionist style of painting, but also embark on a series of narrative paintings based on Hollywood movies in the ensuing years. Significantly, however, Tillim gave Ligare the pathway that would lead to his engagement with classical history, explaining in his 1977 essay why narrative painting was needed, urging “a didactic morality or its equivalent must similarly support and validate what comes down to a new — or renewed — effort to illustrate belief.”

Ligare embraced historical foundational narrative painting at a time other styles were prevalent; yet, Ligare believed it was radical “to make paintings that return to origins.” Declarations of art innovations, or the assertion that something constitutes the status of avant-garde, usually misconstrues the history of art and the inevitable supplanting of one art style or movement for another. For Ligare, this endless cycle distracts us from “the impact that contemporary art might offer to the culture at large.”

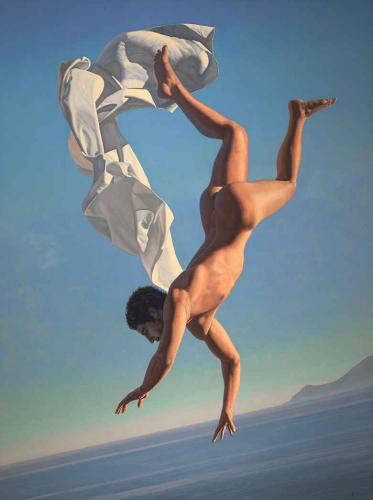

Prior to the foundational narrative work, Ligare made a series of paintings influenced by the remains of damaged and fragmented Hellenistic sculpture; where it was common for appendages to be missing. The remnants of once complete sculptures, usually just comprising the subject’s gown or tunic, nevertheless contained great artistry, evident in the folds of the clothing and still visible shape of the torso. After visiting Greece during a post-high school graduation tour of Europe, Ligare painted a series of draperies floating over the ocean, as if thrown into the air, each named after Greek islands. It was his initial engagement with classical references; one Ligare says was also influenced by conceptual and Pop artist John Baldessari’s performance photograph “Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line” (1973).

The narrative style, which Ligare ultimately made his own allowed him to not only depict scenes he was drawn to render visually, but it permitted him to honor the classical principles he wanted to promote, such as concepts of geometry and balance. Thus, a viewer, ignorant of the foundational narrative presented, could still unintentionally have ideas of measure and harmony permeate their consciousness when looking at the paintings. Ligare’s greater intent, however, was to explore knowledge and certain philosophical ideas, thus, elevating the enduring quality of the pictures he made. These narrative paintings placed him in a rich history of thinking about certain abiding truths and worked to set his work apart from contemporary narrative painters depicting quotidian scenes of contemporary life and modern dramas; ones also evidencing and igniting contemplation of serious ideas, but stories not equally rooted in a tradition of philosophical analysis.

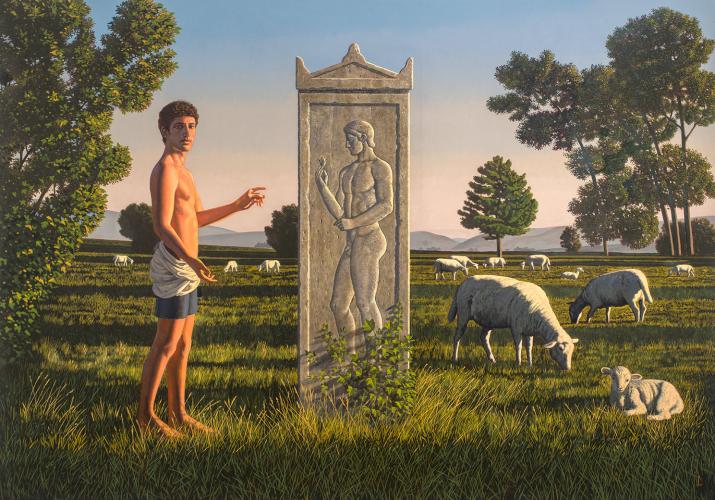

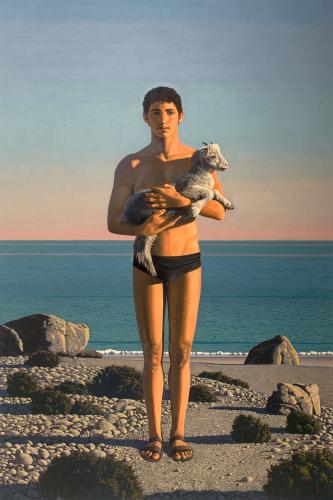

Et in Arcadia Ego / Even in Arcadia, there am I

In the painting of a landscape with “Arcadian Shepherd, or, Et in Arcadia Ego” (“Even in Arcadia, there am I”) (oil on canvas, 50 x 72 inches, 2021), Ligare excavates a classical subject relating to mortality. It references paintings on the same theme by seventeenth century French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin who likewise utilized the shepherd and tomb composition to evoke impermanence. The subject is a pastoral scene, with a curly-haired, bare-torsoed young man standing beside a grave stele, amid a flock of sheep he is tending. The title in Latin alerts the viewer to the message Ligare wants to communicate. The “I” of the inscription references death and evokes a memento mori. Even in this idyllic place, we should be mindful that life is fleeting and there is no permanence; that death is something which awaits us all.

In a version of this theme, painted in 2016, Ligare rendered a carving into the stone sarcophagus he depicted; one with a bas-relief of one of his own narrative paintings, The Death of Patroclus (1986), itself influenced by Titian’s 1558 painting of the entombment of Christ. In the version at LewAllen Galleries, the tombstone has a single male figure holding a flower, as a symbol of the fragility of life. Ligare views the Et in Arcadia Ego trope as essential, noting that it “is an evocation of the ultimate paradox: that we live our lives, ideal or otherwise, with the constant consciousness of our own mortality.”

While other artists have raised the theme of mortality, by doing it in the context of this heavily laden Latin phrase and Poussin’s own engagement with it, Ligare adds a layer to a centuries old theme, thus enriching it and joining a lengthy conversation. Writers from the Roman poet Virgil to twentieth century historian Erwin Panofsky have grappled with the motif and its meaning in relation to the paintings in this particular vein; raising questions as to who the “I” is referred to; the shepherd, the viewer, the unknown person entombed, or death itself? Ligare may be referencing the death of an entire culture rather than that of an individual. Importantly, he doesn’t compel a particular answer; subjectivity is necessarily allowed, but he would insist on the cogency of engagement.

Gustave Courbet: Representation vs Realism

Although Ligare is a representational artist, he stands in contrast to Gustave Courbet, whose Realism was primarily interested in accurately depicting contemporary life, including all of its grittiness and mundaneness. Although Ligare has technical ability to render the figures in what the average viewer would say is realistic, he isn’t practicing Realism, per se; he stylizes his figures, idealizing them by stripping away certain details and blemishes. In doing so, he is careful not to abandon the most important thing about successful representational art — capturing the essential integrity of the person or object seen, a quality we all possess, something that all things are endowed with. This integrity is something separate from exactness or perfection. In this way, Ligare’s idealized physiognomy comes to represent not a specific individual, but all of humanity; paintings of everyman, which if understood within the truths he wants to illuminate, also reinforces that these stories are shared and have a contemporary application.

While Courbet wanted to showcase the common man with exactness, Ligare accomplishes it by illustrating myths that make everyman something more than average; which he does by illuminating truths about being human and highlighting the array of episodes every life contains. Ligare’s characters aren’t performative, they aren’t pretending to be common, they are, in fact, everyman and woman because these moral lessons recur in all lives. Though painting differently than Courbet, Ligare engages the present just as Courbet did. Ligare reminds us that mythology needn’t be viewed strictly as stories about the gods, rather they are about the collision of common men and women with divine forces. He presents his subjects truthfully, without artificiality. Ligare isn’t adding something false as much as polishing the scene to exalt and elevate it, commensurate with its status as myth. Doing so doesn’t make it precious but projects a grandeur that encompasses the majesty of a culture.

Polykleitos & Symmetria

To achieve representational integrity within the tradition of Classicism, Ligare employs Greek polycletian sculpture as a reference point. Utilizing photography, he places images of a ancient plaster or marble cast into the pose he is rendering, in effect, melding it with the reference photos of a model he is working with – which lays a groundwork for the classical look he seeks to achieve. The ancient notion of balance between antithetical forces is a recurring classical theme and critical to understanding Ligare’s attitudes toward the structure of a painting. In this way he is indebted to Polykleitos, the fifth century BCE Greek sculptor from Argos, who cared how one arm should be rendered while maintaining balance with the another. Not in exact symmetry, but rather, he reflected on the push and pull of presentation; one arm might be directed forward, while the other, in contrast, bent in another direction. Polykleitos opined on the rotation of a torso and the proper way a person’s head might be depicted slanted. His reflections in this sense comprise a sort of early Vitruvian Man; Polykleitos sought to define ideal measures.

Polykleitos called his system of proportions symmetria, which doesn’t translate directly as symmetry, but constitutes the balance of things that are fundamentally unequal. Just as various body parts have different functions, symmetria is the harmonizing of these units in relation to one another. Polykleitos was indebted to Greek philosopher and geometrician Pythagoras (active in the late sixth century BCE), who first explored harmonic integration, particularly as it related to numbers and patterns in visual phenomenon. Both agreed that symmetria was not just the proportions of the body but also referred to the laws of nature and the functions of people in an integrated society; a kind of commensurability and integration of the parts.

Although Polykleitos’ treatise on the mathematical basis of the idealized male body shape did not survive into modernity, nor any of his own sculptures, marble copies of them by Roman carvers do exist and are highly prized (for example the Doryphorus, or “Spear Bearer,” in the Museo Archaeologico Nazionale, Naples). It is these Roman versions that Ligare references as he seeks the integrity of his own subjects.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

By the time Ligare began his foundational narrative paintings he was already paying close attention to sunlight; gradually it came to represent truth and the illumination of ideas. Having grown up near the beach in Southern California and working outdoors as a plein air artist, Ligare was grounded in the role light played in both highlighting and unifying areas of a composition, affecting surface and contours throughout. Soon, he felt its symbolic importance and how it could be equated with knowledge, erudition, and learning. Ligare has called it “a symbol of radical knowledge” suggesting linkages with enlightenment.

Ligare utilizes late afternoon light in his paintings to represent the passage of time and the exhaustion of daylight as if to augur the impending arrival of darkness. The threshold between day and night, what is referred to as “the golden hour” has rich symbolism attached to it. Ligare has said “I love the radical beauty of this late afternoon light with its attendant shadows because, despite its brightness, there is a melancholic edge to it, a reminder of mortality.” Importantly, the light source in Ligare’s work is usually entering the composition from the left or right, low and at a right angle, heightening the sense of approaching change and drawing analogies to the vagaries of life. As a result, subjects are depicted in partial light and shadow, and contain the balance of opposites so critical to ancient Greek thought.

Ligare references Plato’s iconic “Allegory of the Cave” when discussing the importance of sunlight. The contrast between the primacy of sunlight against false light of the cave is meaningful to Ligare, given that the illumination of ideas is at the core of his artistic purpose. Plato’s allegory (presented in his Socratic dialogue “The Republic,” circa 375 BCE), posits the question whether education and exposure to truths can overcome the shadows projected on a wall; images that only approximate reality. As Ligare is well aware, and which Plato appears to have wanted to expose, many don’t want to be liberated, preferring the familiar, regardless of its approximation to truth, or lack thereof.

In the allegory, Socrates is in dialogue with Plato’s brother Glaucon. Socrates relates the tale of a group of persons who spend their entire lives chained to a wall of a cave. They live facing the wall and only observe shadows projected from things passing before a fire behind them. The shadows come to represent the only reality these captives are permitted to experience. Socrates is interested in what happens when a prisoner is liberated from the cave, and encounters the sun, in effect when they experience truth. Plato calls the sun “the guardian of everything in the visible world.” Yet, the irony, regrettably, is that the other captives are content to live their lives in ignorance.

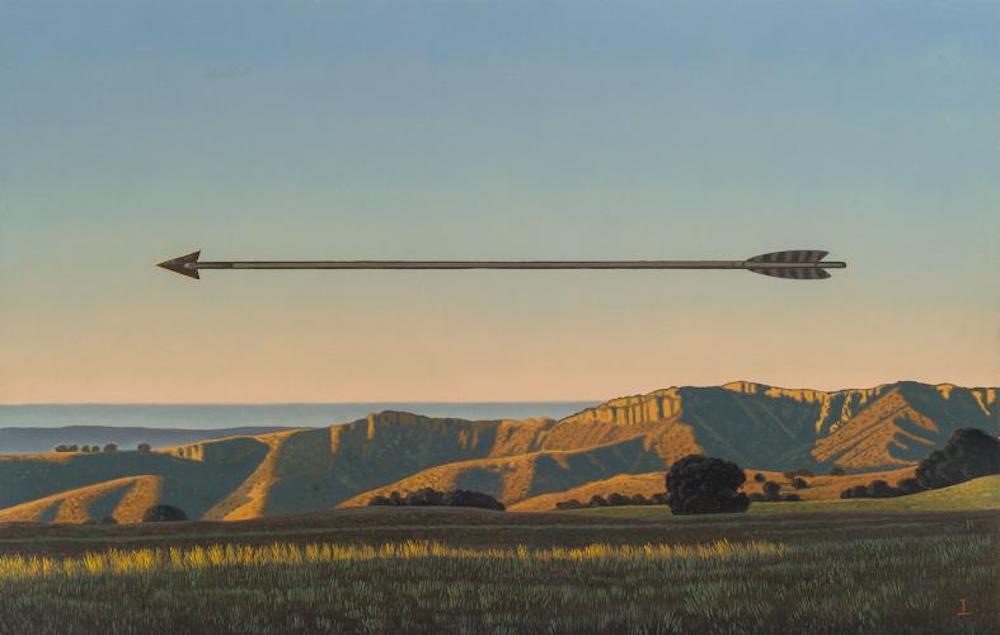

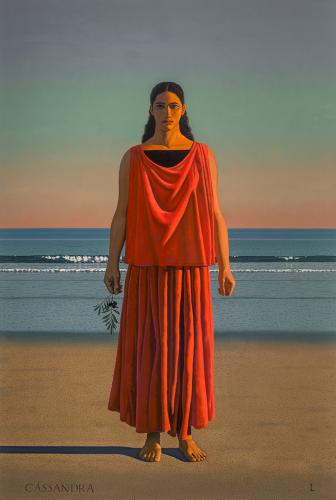

Cassandra & Landscape with Arrow

Two paintings in the LewAllen Gallery exhibition allude to Ligare’s frustration with contemporary society afflicted with what he believes is a dearth of knowledge, akin to the ideas Plato exposed in his allegory. He contrasts this with Classicism’s engagement with ideas and desire for erudition. In contemporary society, a large number of people treat falsehoods, even those demonstrably wrong, as trustworthy. Science is discounted, and politicians elude accountability by inventing counter-narratives filled with deceit. Ligare’s wish to inspire greater knowledge through painting seems implausible viewed within this backdrop. Yet, he stands by a belief that the job of culture is to make us want to be educated.

Ligare’s painting “Cassandra” (oil on canvas, 72 x 48 inches, 2021) could easily be self-referential. She knew the calamities that awaited but no one would listen to her. In Greek mythology, Cassandra is a particularly tragic figure. The god Apollo admired her for her beauty and gave her the power to foresee the future, but after having his amorous advances rejected, he cursed Cassandra by making her prophecies disbelieved. Ligare depicts the seer staring directly at the viewer as if imploring action; urgently waiting for it. The younger sister of Hector and Paris, Cassandra was taken by Agamemnon of Mycenae as his slave mistress after the sack of Troy. Later she would befall the same fate as Agamemnon; she was killed by his wife Clytemnestra.

In “Landscape with Arrow” (oil on canvas, 20 x 32 inches, 2021), Ligare paints an arrow seemingly floating in the sky. It’s pointed right to left, in contrast to the usual left to right composition that Western culture favors. Ligare is pronouncing the need to engage and learn from the past. He notes that "[u]sing history allows us to look past all the superficial and sometimes distasteful aspects of ancient cultures (as well as our own), to focus on the extraordinary achievements of the ancients and to hold them as examples of how to think deeply, how to act using rational judgment and to instill an excitement to excel.” Ligare’s belief that history can teach and steer us forward remains inviolable.

Ligare’s ideas continue to reverberate because they are inexhaustible in their deeper meaning and tethered to a rich history of philosophical engagement, evidenced by the many thinkers who have grappled with the meaning of beauty or justice, or any of the questions of morality relevant today. For Ligare, these paintings battle anti-intellectualism because they stand against any sentiments denigrating erudition. They are meaningful voices within the traditions of liberalism; a heritage teeming with lessons for humanity. But we, the viewers, must be brave enough to engage with these pictures. Ligare declares that “This is now the job of culture: to make us want to be educated, to ignite our passion for knowledge and to inspire us to think as deeply and as creatively as the ancients.”

Ligare isn’t a painter for a disengaged audience. To understand his canvases a viewer has to immerse themselves in rich ideas. Those who wish to forgo the experience, for lack of commitment, miss the opportunity to gain a breadth of knowledge that won’t be achieved looking at artworks that skim the surface with effortless ideas. Yes, all art offers something to learn, but Ligare urges and even compels a more erudite engagement with enduring ideas. The reward, embedded in what it is to be virtuous, promises to be long-lasting. –Matt Gonzalez

"Presence of the Past,” at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico, through January 8, 2022

Sources:

J.J. Pollitt, “Art and Experience in Ancient Greece,” (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1972).

Sidney Tillim, “Notes on Narrative and History Painting,” in Artforum (May 1977).

“[Untitled artist statement]” in “David Ligare, Paintings,” (Monterey, CA: Monterey Museum of Art, 1997).

Elaine Scarry, “On Beauty and Being Just” (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

David Ligare, “John Steinbeck and the Pastoral Landscape: An Artist’s Viewpoint,” Steinbeck Studies (The Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University), Fall 2002.

“Critical Reconstructions, An Interview by David Rush,” in David Ligare, Aparchai (San Francisco: Hackett-Freedman Gallery, 2007).

“Artist Statement” in “David Ligare, New Paintings,” (New York: Hirschl & Adler Modern, 2012).

David Ligare, “On Using History,” (Monterey, CA: Cypress Press, 2016).

James Nisbet, “History Painting after Conceptual Art,” in “What Was History Painting and What Is It Now?,” eds., Mark Salber Phillips & Jordan Bear, (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019).

“[Untitled artist statement]” in “David Ligare, Elements,” (Santa Fe, NM: LewAllen Galleries, 2019).