"What does this white girl think she’s doing? is a question that comes up in the art world regarding my paintings that include black figures. I’ve been asking myself that question for the last five years and will do my best to answer it here." So begins Oakland, California-based painter, Cate White, who was featured in Juxtapoz a few years back and is set to open her new solo show, My Best Unbeaten Sister, at Guerrero Gallery in San Francisco on February 23, 2019 (her second solo with the gallery). The following essay that Cate penned about the show is both an insightful, bold and vulnerable story about the art-making process and Cate's life as an artist. Please read, in her words, an excerpt from White's essay on the making of her new work.

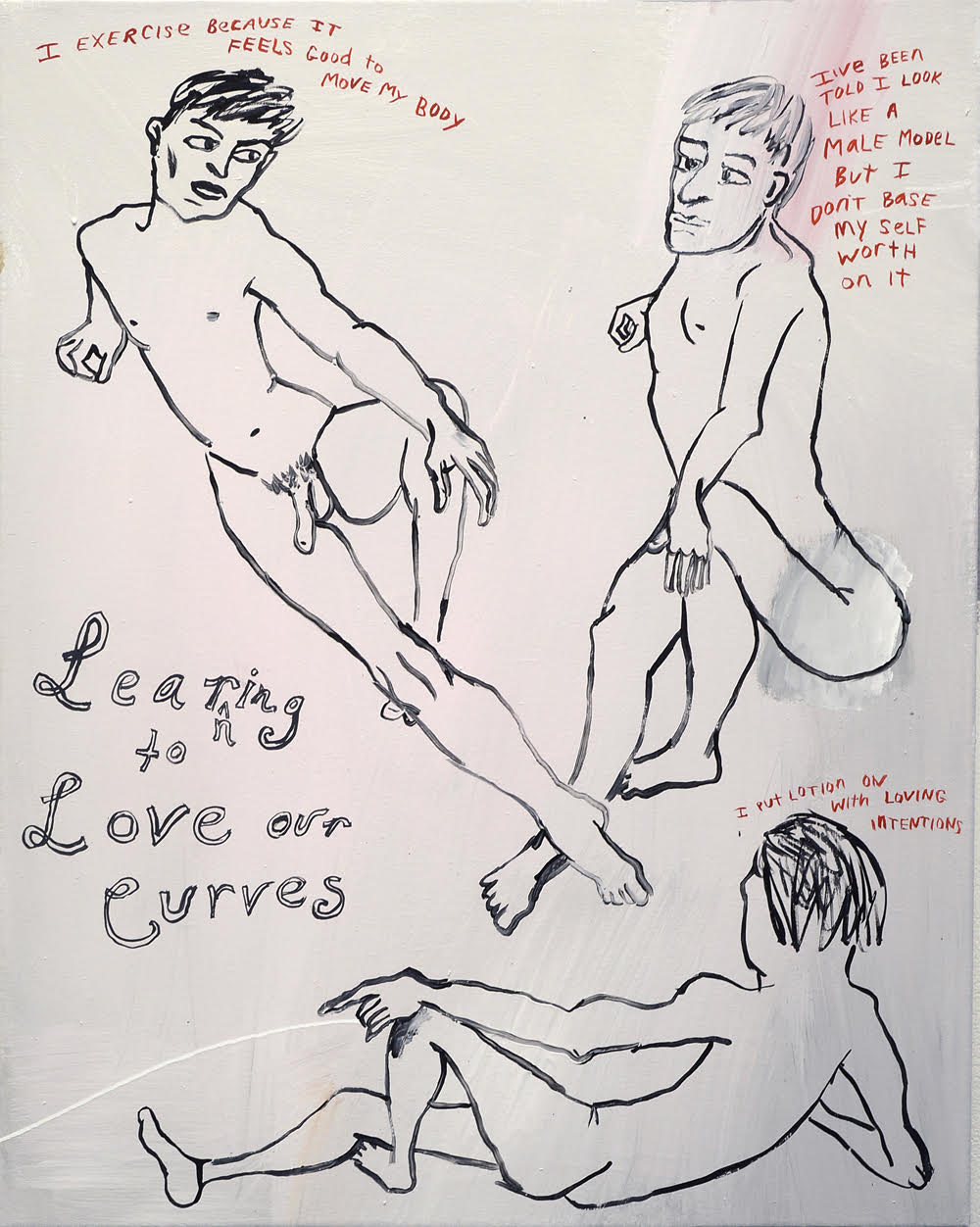

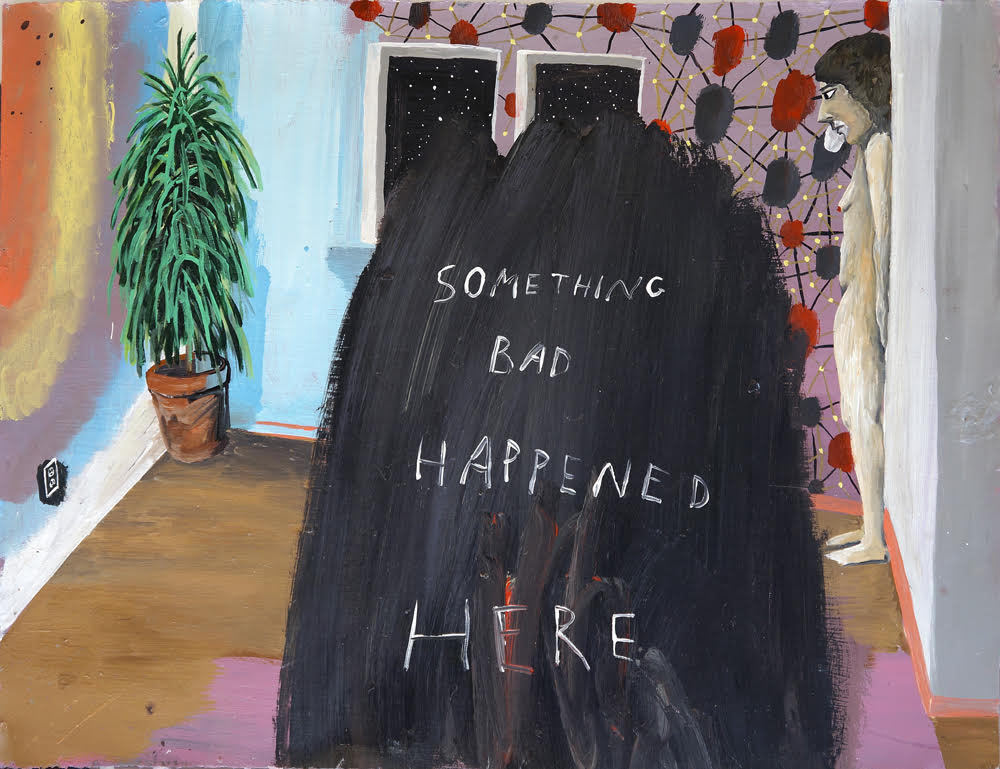

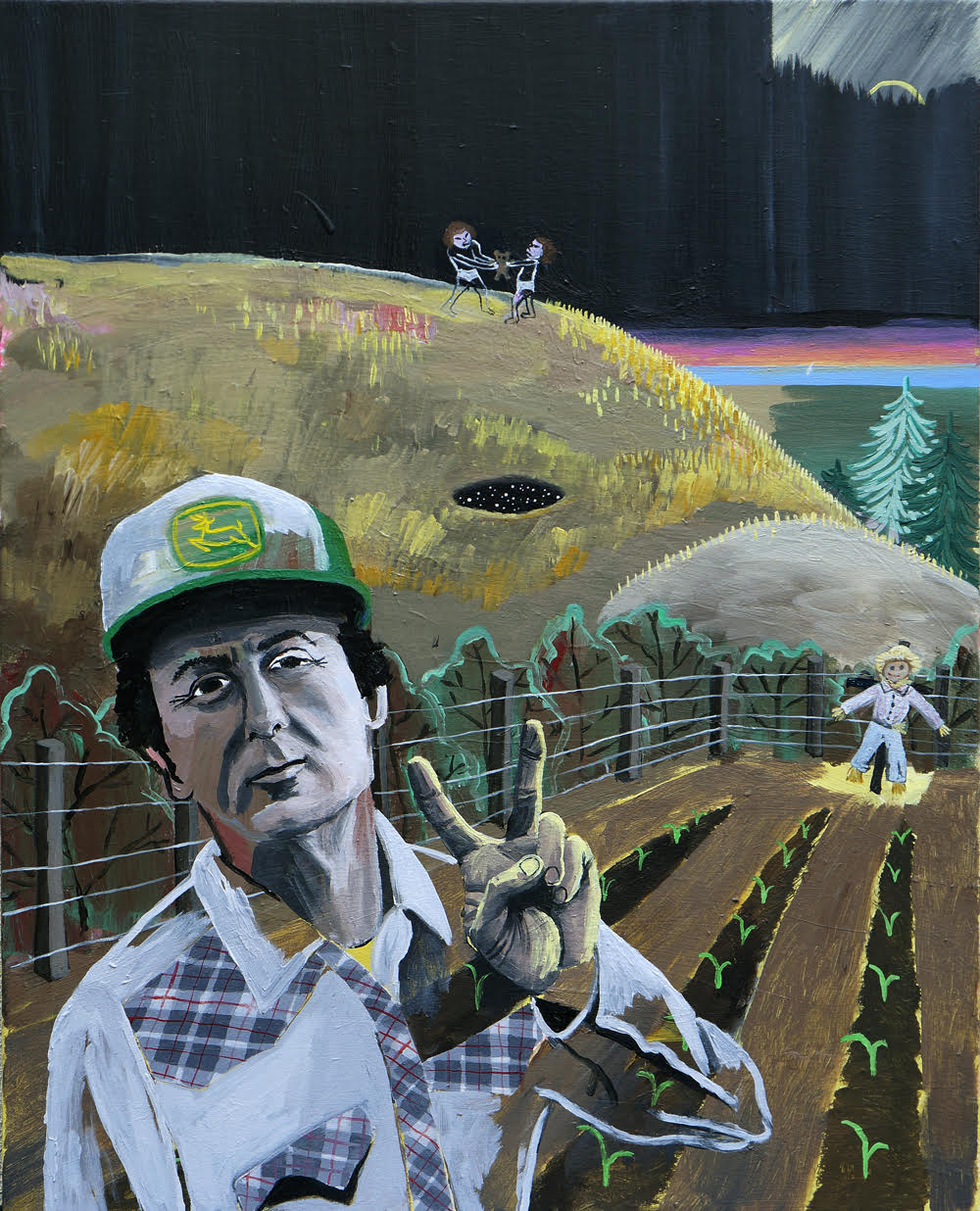

My primary aim in doing my art is to break down and through my own conditioning as a product of “imperialist, capitalist, white supremacist patriarchy.”1 I do this for my own psychic survival. Painting and drawing seem to be somewhat effective tools for this in a possibly mystical way that I won’t get into here. In making my work, I find glimpses of freedom, truth, love and my untrammeled humanity. This process of expanding awareness continues in the public dialog about my work—for me and for others.

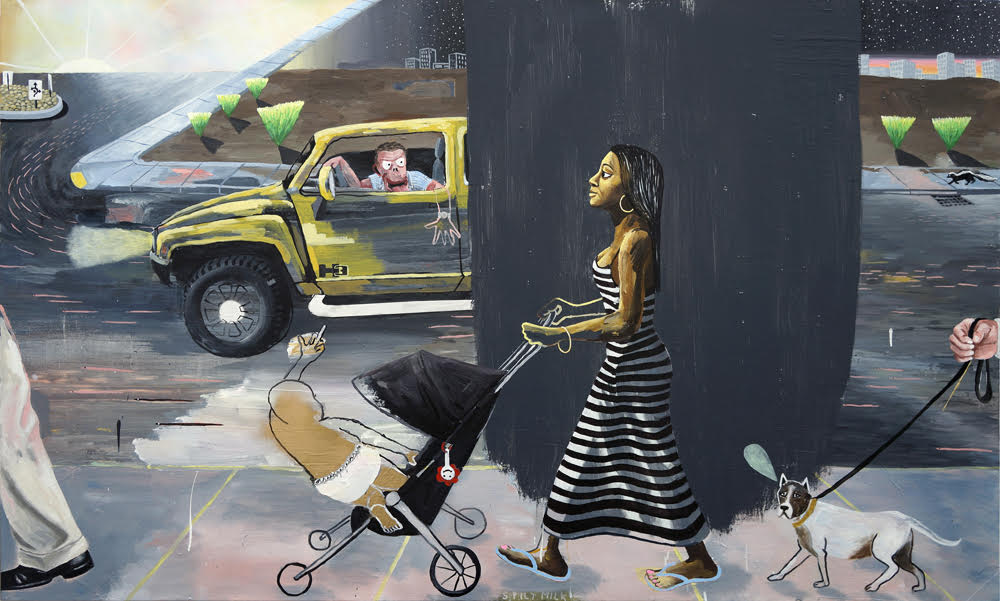

Since my work became public in the art world five years ago, questions regarding race and representation have arisen. The general stated concern is that the historical power dynamic of white people representing black people in inaccurate, exploitative or inhumane ways could be happening in my work. It seems a simple question to answer. Look at the work itself and decide for yourself. This is how my work is evaluated outside of the art world, and the response to inclusion of black figures in my work has been the assumption that here is an ally. I don’t report this as a defense of my work, but as a point of discussion. Why such a starkly contrasting response in the art world, where my inclusion of black figures is sometimes charged with discomfort?

I’ve been grappling for the last five years with this gap in the meaning of representation: through reading, writing, introspection, rumination and ongoing, in-depth conversations with people of color from the street to academia. What I’ve come to know is that there are multiple perspectives and voices that need to be listened to if we want to have a clear grasp on reality as it’s experienced by the collective. We don’t listen to outside perspectives to be nice. We do it because we need them. As bell hooks writes:

“...the margin is more than a site of deprivation...it is also the site of radical possibility, a space of resistance...a site one stays in, clings to even, because it nourishes one's capacity to resist. It offers to one the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds."2

Here is an example of a perspective from outside the art world that feels radical within the art world:

I make my work in a mostly black neighborhood and my social life is racially integrated, so a lot of black people—friends, neighbors, etc.—see my work before anyone else and are part of the conversation before it goes public. People like to give me suggestions for paintings they think I should make, such as, “Hey, you should paint a tribute to Nia Wilson” (the black girl who was murdered on Bart by a white man in July of 2018). When I tell them how badly their idea would go over in the art world, I see confusion and hurt in their eyes. I have to tell people that within the art world, they are seen as different from me. When I asked Rory what he would like people in the art world to know about people in the streets, he said, “I would like them to know that we are no different than they are.”

Seven years ago, before my consciousness had made the full perceptual shift into integration, it didn’t occur to me to include black figures in my paintings. I remember asking Rory what he thought of what I had made that day and he said, “It looks like a bunch of white people.” That’s when I first realized how my perception was skewed by racial conditioning and suddenly my work looked like a bunch of white people to me as well. Within the art world, the inclusion of black people in my paintings arouses suspicion rather than indicating an integrated life.

These marginalized perspectives are sometimes dismissed as uneducated, uninformed or unenlightened. So, I’ve made a practice of finding links between street wisdom and more “credible” cultural production. Here, Hilton Als, writing about Alice Neel, repeats and expands Rory’s perspective:

“What struck me about her vast oeuvre… was all the people of color she painted. This was unusual, and is still. The truth of the matter is that many—most—contemporary artists of non-color are interested in reflecting themselves, their creamy whiteness and hair untroubled by thought. On the flip side, many artists of color who make a buck nowadays do it by equating blackness with oppression and selling the result to white people without feeling a thing for their subjects’ lives. Neel’s work smashes both of those categories, showing us the humanness embedded in subjects that people might classify as ‘different.’”

Please read the rest of the essay on Cate White's site, here.