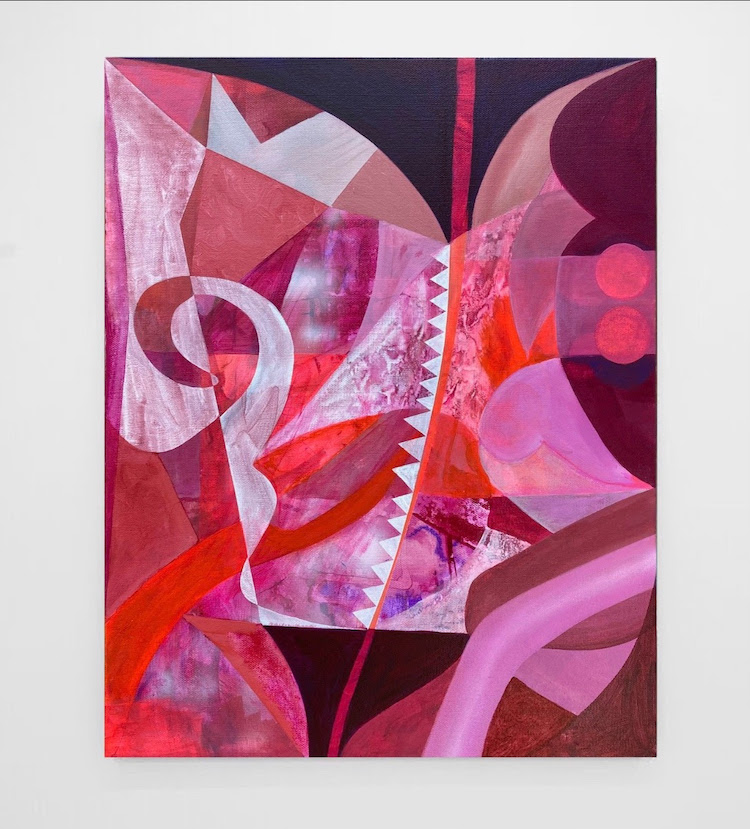

See yourself in a forest rife with color and shape. Vines climb to waving canopies. Ferns bunch in fractals at the feet of trees. Peel back the soil to find the roots’ spindly fingers woolen with fungal filaments. They reach out to one another, interlaced in rhizomatic discourse. This is life as found in Brett Flanigan’s Life Paintings: depictions not of natural life but of the systems and patterns that engender life.

Dying trees may bequeath their carbon-stores to neighbors. A Douglas fir has been observed to warn nearby ponderosa pines of danger.

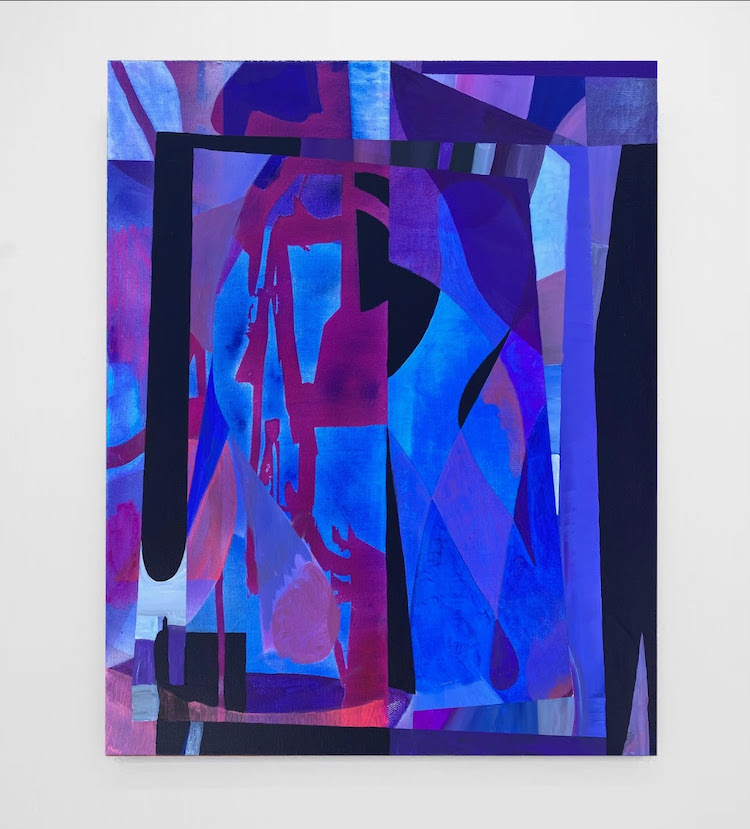

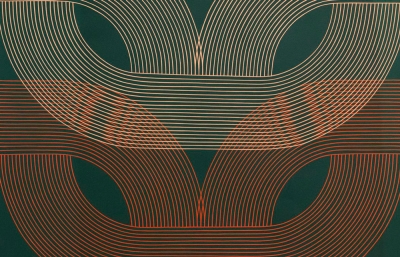

These are works deeply informed by process. Flanigan’s practice operates as a kind of biological or evolutionary system. Given a set of initial conditions (color, size, the unconscious marks of their inception), the paintings grow as organisms in an ecosystem, sharing the nutrients of shape and texture, gesture and color. A pattern here, shown to be beneficial, appears elsewhere, altered but recognizable. A line in one painting mutates into erasure in another. Seeking homeostasis, they encounter chaos and error—mutations to which the system must respond.

“The capacity to blunder slightly is the real marvel of DNA,” wrote doctor-poet Lewis Thomas. “Without this special attribute, we would still be anaerobic bacteria and there would be no music.”

Our notion of a “natural” process is disrupted, however, by the evident use of technology: gestural marks generated by a computer, applied via vinyl plotter; the way a line looks when drawn on a mousepad. What is “life” when we have merged the artificial? Is AI another mutation to be integrated into the system? Or is it a mutually beneficial relationship, like the fungi that fuse to root systems to form mycorrhizal networks?

Chemicals found in fungi are also found in lobsters and crabs. Anemones that attach themselves to crabs are able to recognize the shells’ molecular structure. The crabs, in turn, can recognize their own anemones and will attach them like ornaments to their shells.

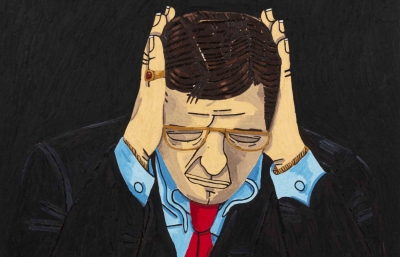

The works that comprise Life Paintings depict a kind of sinking into life, a microscopic view of life’s movements and rhythms. They are, as Flanigan terms them, Abstract Realist. It’s as if we’ve gotten so close to reality we’re seeing it at a cellular level. Here are the ruptured organelles of experience and emotion.

Certain 19th C. biologists believed there was a substance within all living things that made life and the mind possible. Dredging the bottoms of ocean, they searched for organisms that would reveal the stuff of life.

They would’ve found it in Life Paintings. —Mark Haslam