Bill Brady Gallery is pleased to present Good Grief, an exhibition of recent paintings by Jess Valice.

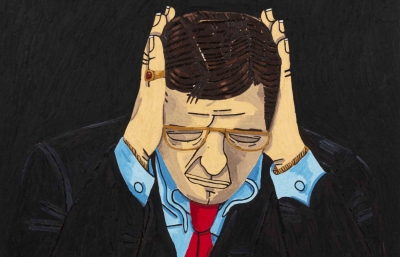

You won’t notice the droplets of blood at first. You’ll be too distracted by the physicality of the body before you, with its distorted proportions and grotesque features. You’ll follow a thigh or thumb or a neckline, a clever Boterismo technique, but the real story is in the face; soon, you’ll make out a mouth that isn’t really there. Then the uber-pinched nose, which leads you to two bulging saucers (think Margaret Keane and her big eyes attached to a Carroll Dunham nudes). But then, as you get closer, maybe a bit introspective, certainly more curious, you’ll sense a profound, abject sadness in the subjects. It’s hard to say why, but it’s there. The warped proportions become MacGuffins concealing more to the story: a bleeding finger, a syringe, an open window.

Jess Valice’s figurative portraits—cartoonish in style, ambitious in scale—are an ongoing study in the absurdity of human experience. As cells, we are born to die, that’s our definition, and it’s something Valice, a 25-year-old pre-med dropout, knows intimately. She’s lived and worked within the paradox of memento mori since her father’s death in August, finding comfort (maybe even purpose) in the human ritual of bereavement. “Good Grief,” the artist’s debut solo show at Bill Brady Gallery in her hometown of Los Angeles, is a compendium of those two opposing thoughts, finding a happy medium in the waves of loss and mourning against celebration and art.

Zooming out, you’ll begin to appreciate the playful and crude narratives that embellish the 11 paintings. One pours coffee on his own hand, another stretches topless while two wander at sea in a punctured raft. Throughout, they remain ostensibly expressionless; their biomorphic eyes and ears offer no clues. There’s a hilarity to the strangeness, a deadpan reaction to uncertainty and pain and adventure. Like how an ear canal or an iris can function as a thumb print—each one unique to its owner, fully formed at birth, unmistakable under magnification and focus—the many faces of “Good Grief” share a quality but not a story. That you have to find on your own.

Written by Mariella Rudi