This is our second in a series of reviews and write-ups on Chelsea Wong's solo show, The Pleasure of Joy, at Legion in San Francisco. Earlier today, Tamsin Smith wrote an extensive piece, and now we have a write-up from Matt Gonzalez.

Looking at an exhibition by Chelsea Wong is a lot like scrolling through someone’s fun Instagram feed. There are picnics, dance parties, and lounging on the grass drinking prosecco with friends; again and again, optimism pervades every scene. When a person promotes such images on social media, skepticism causes us to wonder whether something is being hidden from us. Life can’t possibly be this charmed. In her paintings, Wong amplifies real life moments to comment on how we should be living, not for the sake of boasting, but as fully evolved human beings at peace with ourselves and our community; the backdrop being the canopy of urban life with all of its persistent conflict.

The historical traditions of a “philosophy of optimism” are said to originate in the religious pronouncements of Gottfried Leibniz, who during the Enlightenment posited a defense that the social order is as it should be, since God made it, thus necessitating an acceptance of inequality. Wong isn’t propping up that kind of optimism. Rather her work is anchored to the ancient Aristotelian idea of ethics, which the early Greek philosophers grappled with posing the question, “how should people best live?” They ruminate that the purpose of life is to attain eudaimonia, a Greek word meaning happiness or human flourishing. For Aristotle, achieving that is rooted in developing excellence of character and virtue, which manifests in a person’s good conduct.

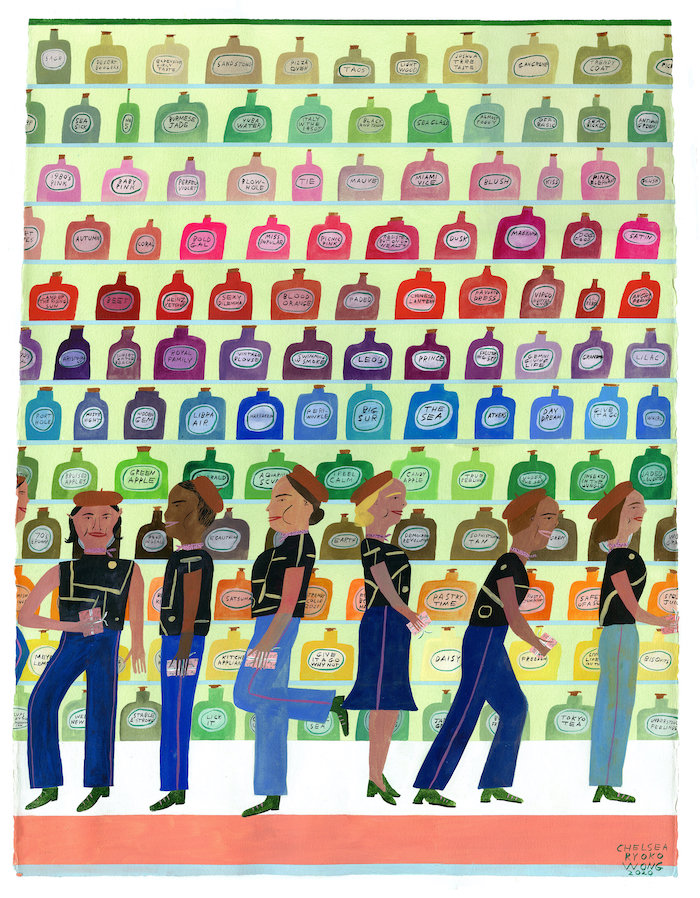

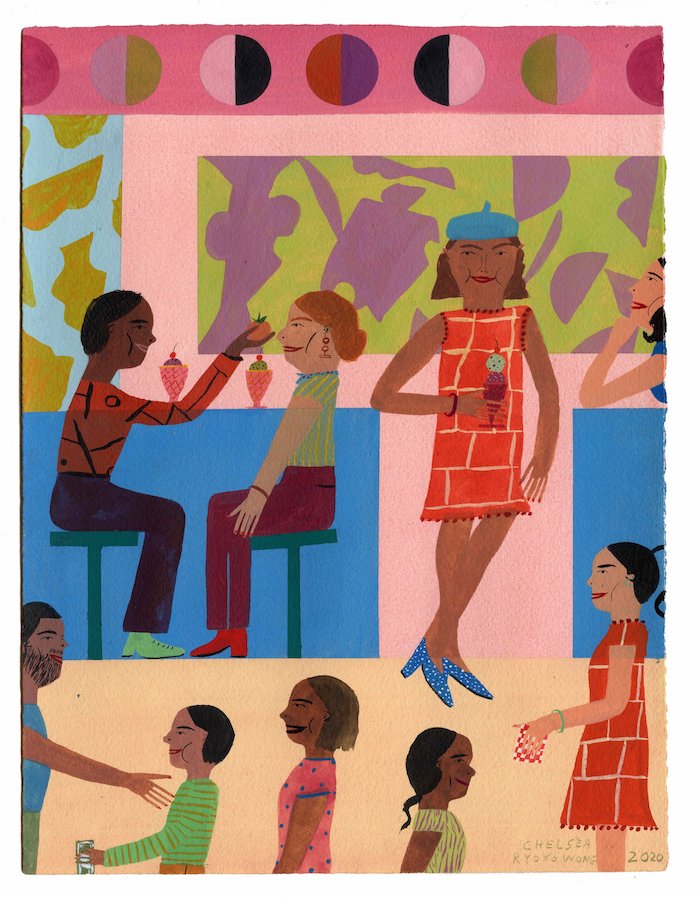

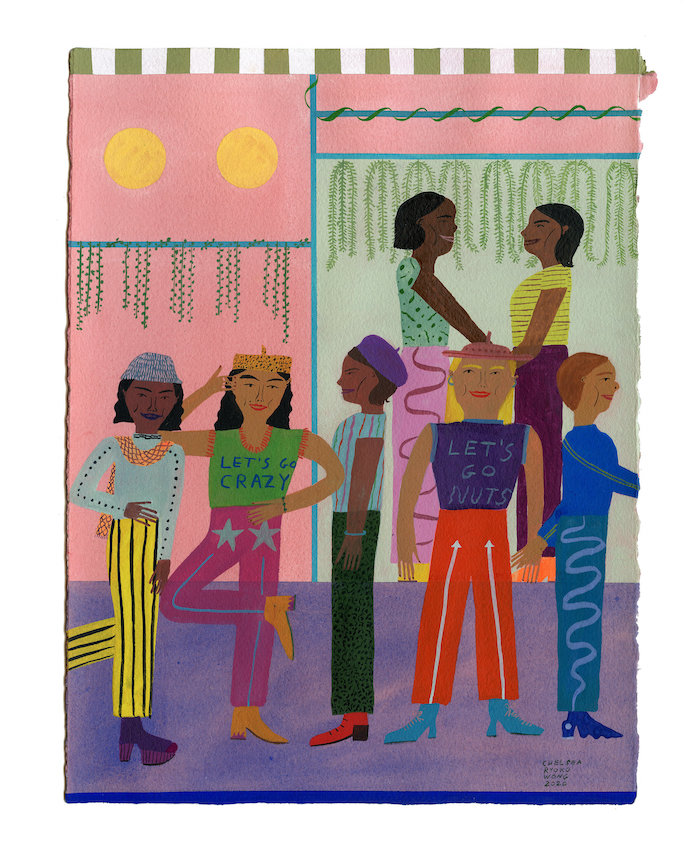

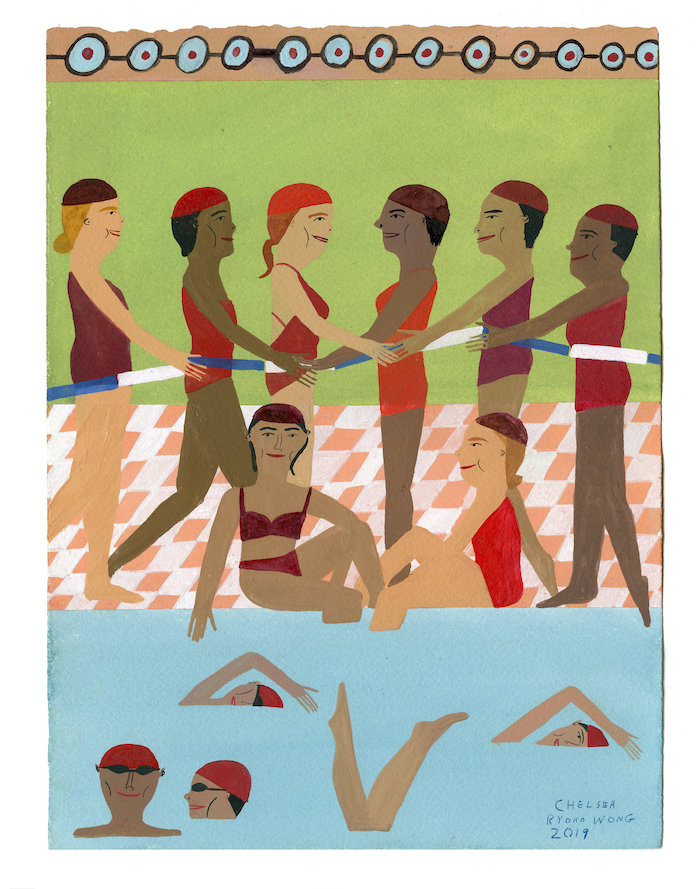

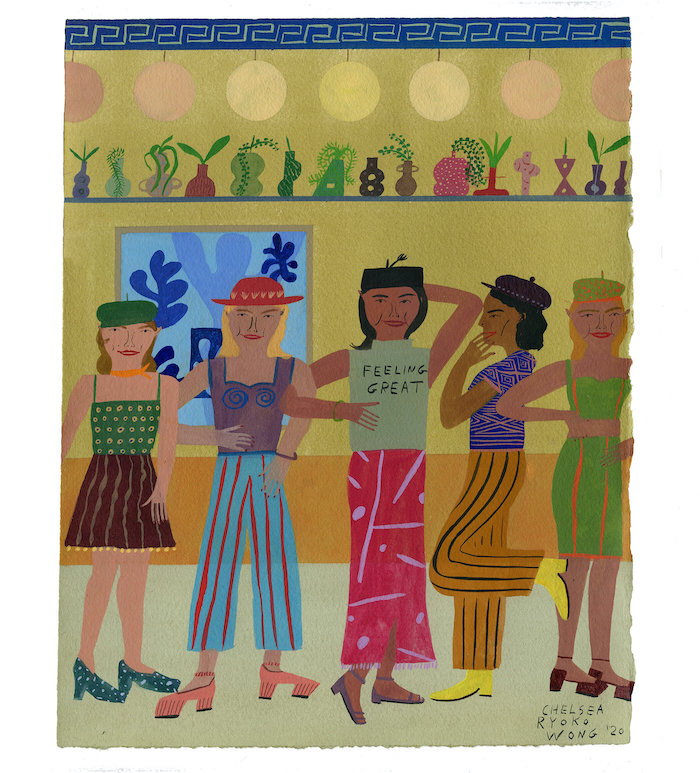

In Wong’s work we reductively grasp the actions of her painted figures, hopefulness and positive energy abound, suggesting the innate virtue of her characters. Even in the face of adversity she presents human flourishing and all of its prosperity. The show at Legion is aptly titled The Pleasure of Joy and Wong does just that, she paints the best aspects of life helping us imagine what it should actually be like. She presents her cast enjoying ice cream together, shopping at the market fruit stand, gathering at rooftop soirees, swimming at Garfield Pool, holding hands while dancing, and foraging for freshwater mussels on the Russian River. Viewed another way, her characters are physically exercising, talking about politics, and showing empathy for one another.

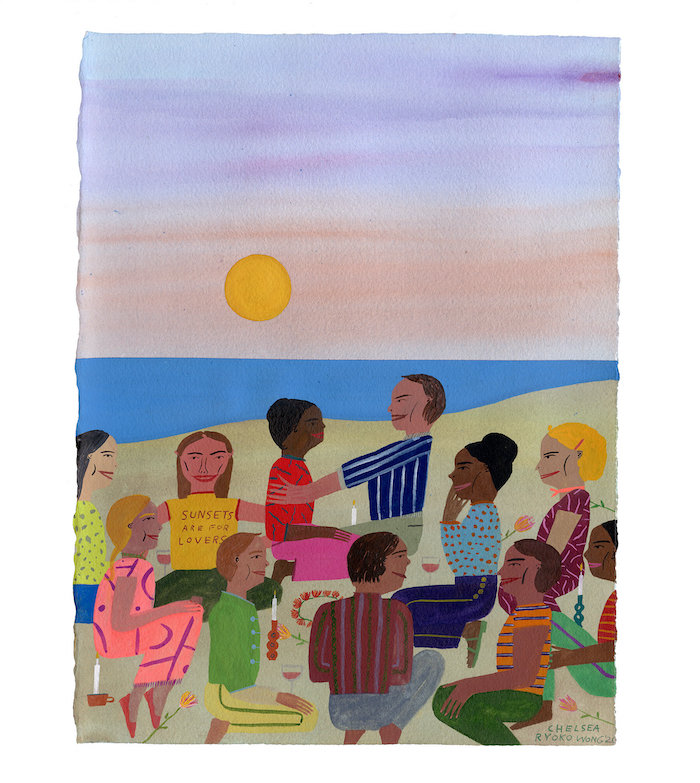

The curated selection of positivity can be seen as an epilogue, one augmenting the hopefulness that we can only partially imagine now, but which awaits us if we work towards it. In a recent Instagram post, referring to her painting Sunsets Are for Lovers on a Warm and Windless Night, Wong notes “This is just about the opposite of what it’s like IRL [in real life] right now, but hey a girl can dream.” She both articulates her aim and reminds us of what we must do, even during a health pandemic and/or social upheaval, to promote community and attain fulfillment.

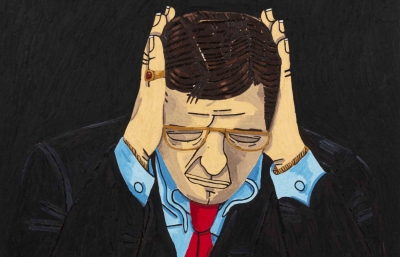

While Wong is a painter of optimism, avoiding anything akin to frustration or anger in her work, an obvious contemporary artistic antecedent is Mission School artist Chris Johanson, who also drew and painted flat figures in various urban scenes. But Johanson captured the negative energy of the 90s in his early work. In an interview with Corrina Peipon published in 2013, Johanson noted “I think what happened there was I’d just moved to San Francisco, and I started to make these pictures about people in the neighborhood. That was definitely coming from a dark place because I was pretty dark then. I think I had a lot of anger and a lot of anxiety. I think in some regard I’m like a documentary picture maker, so I’ve always just been painting pictures of stuff around me, just reacting.” By contrast, Wong isn’t interested in negativity, she promotes a better world because she has already experienced it in fragments and can imagine it amplified. Multiculturalism and racial integration permeate Wong’s work, again suggesting that a day of harmony is possible.

In Glowing River with Tutuola, Wong references the Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola, whose Grove-Atlantic dual edition of The Palm-Wine Drinkard” and “My Life in the Bush of Ghosts” is painted next to a sunbather reclining on a beach towel, letting us know that even in moments of repose we must nourish our minds. Other still-life objects such as sunglasses and arrangements of balanced stones, the latter suggesting awareness and patience, help fulfill the composition.

Wong also integrates text in some of her paintings with logos her characters wear on t-shirts or by posting banners at the top of the paintings. In Stronger Everyday, Unstoppable the notice says in capitalization: “Songs for energy. Sunshine for joy. High up places clear the mind, clear the clouds. Beaches are for lovers and for the brokenhearted too. Friendship cures loneliness but a pet or pet rock will do. I feel stronger every day, life is grand, life is sweet.” Her exuberance for living, and her channeling of eudaimonia and the uplifting of spirit, is on full display. In the same painting one of her characters wears the slogan “You can be sure I’ll be here” on her sleeveless blouse; and yes, this exhibition attests that Chelsea Wong brings it with her affirming voice and vibrant brush.

Wong’s show of colorful utopian paintings will be on display for another week at Legion, a design shop and art gallery in San Francisco, located at 808 Sutter Street (currently by appointment). All works are from 2020 and range in size from 60 x 48 inches to 15 x 12 inches. Mediums utilized include acrylic on canvas, and gouache and watercolor on paper. —Matt Gonzalez

Chelsea Ryoko Wong, San Francisco-based painter and muralist, studied at Parsons School of Design in NYC and completed her BA at California College of the Arts in printmaking in 2010. She can be found at @chelsearwong on Instagram or at her website: https://chelseawong.com/. Her show at Legion SF is viewable online.