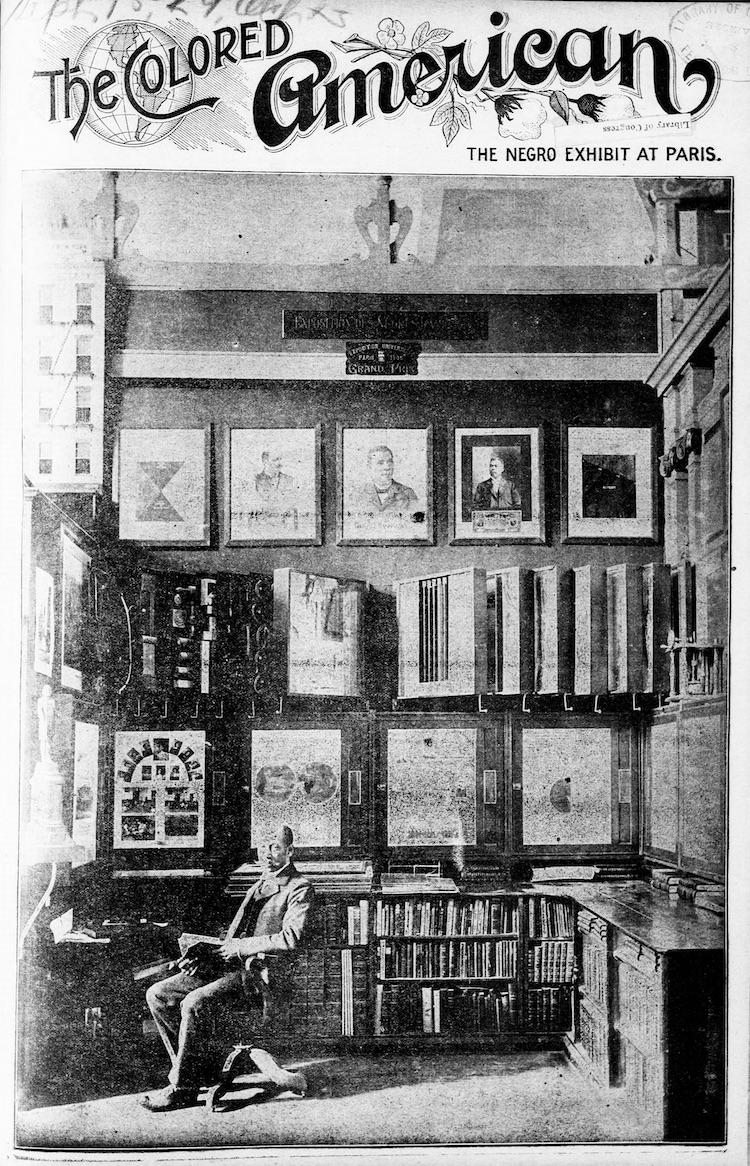

Oakland Museum of California has produced a moving, immersive journey, aptly described by curator Rhonda Pagnozzi: “Afrofuturism is sort of like a filter that can be applied to any aspect of life. It is a theory of knowledge. It often collapses the past, present, and future into a singular experience or recontextualizes a historical moment. By restructuring time or recontextualizing history, Afrofuturism provides a platform for reclaiming Black narratives and creating bold territories. This is why it was important to highlight historical moments in the exhibition; to showcase Afrofuturism’s ability to bend time to reveal present day truths.”

Pagnozzi generously shared some stories from her creative process, “It is sort of like writing a song, finding a series of right notes that will illuminate the story you are telling,” she mentioned, exemplifying the artistry behind a curatorial practice.

Juxtapoz: Parliament Funkadelic’s Mothership is a central feature of the exhibit. Was it an anchor point for the concept?

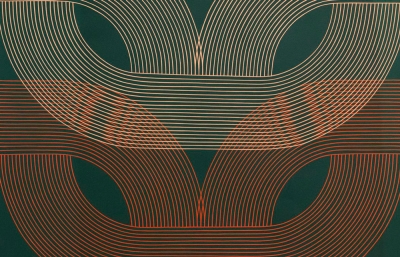

Rhonda Pagnozzi: While the replica of the Mothership anchors the physical space in the gallery, I wouldn’t say P-Funk was necessarily an anchor point. But the music and mythology of George Clinton and his bands are undeniably central features of Afrofuturism, so it was important for us to showcase their work and influence. By merging soul with psychedelia, space travel, ancient Egyptian and Black iconography, P-Funk created the classic Afrofuturist mythology.

As the exhibit developed, the symbolism of a “Mothership” beyond P-Funk started to drive many of the other concepts. These ideas emerged in the themes of intuition, Black spiritual traditions, and community-building grounded in Black feminism.

I have been in contact with George Clinton Enterprises since the beginning of the project. I have mostly been in communication with his artistic director Overton Loyd and then with his wife Carlon Clinton and their gallery director. They have been very supportive of the project and Carlon said she and George may even come to see the show, which would be very exciting!

What were the challenges to recreate the epic Mothership, and tell us about its interior video installation.

My vision was to showcase the original Mothership stage prop from the P-Funk concert performances. Apparently, there are a couple of them, and they have their own myths surrounding their whereabouts. One of them is the National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian in DC. I visited with Kevin Strait, the lead curator of the Musical Crossroads installation, where it is on view. He was very gracious, but they weren’t able to loan it out at that time. When I shared this news with the team, they offered to build one. They did a fantastic job paying tribute to the iconic symbol. Our crew was committed to making it a quality spectacle. I love how it turned out. OMCA’s staff are a deeply talented group of people. I’m so grateful to have the opportunity to work with them all.

The video installation is a recording of a performance during P-Funk’s 1976 Earth Tour. In the footage, The Mothership is summoned down for George Clinton to emerge. Hearing Glen Goins incorporating Black spiritual sounds into the Mothership Connection as he summons it to earth is a beautiful companion to the installation. It illuminates P-Funk’s unique combination of theatrics and humor grounded in historical legacy. As the lyrics go, “We have returned to claim the pyramids.”

We commissioned Paul Miller, AKA DJ Spooky, to curate the Spotify playlist available for visitors to listen to while standing in the Mothership. He selected over 165 songs accompanied by brief essays. In one essay Paul wrote, “I chose these songs as threads in a tapestry woven from several centuries of the Black experience, reflecting a Diaspora condition. African American music has set the tone for 21st-century global culture. From blues, jazz, rock, to electric minimalism, you will hear the logic of Diaspora reflected in this complex mix. In one way or another, we have created a new dimension in culture—one from sound.”

All exhibitions should have soundtracks. Tell us about more anchor works.

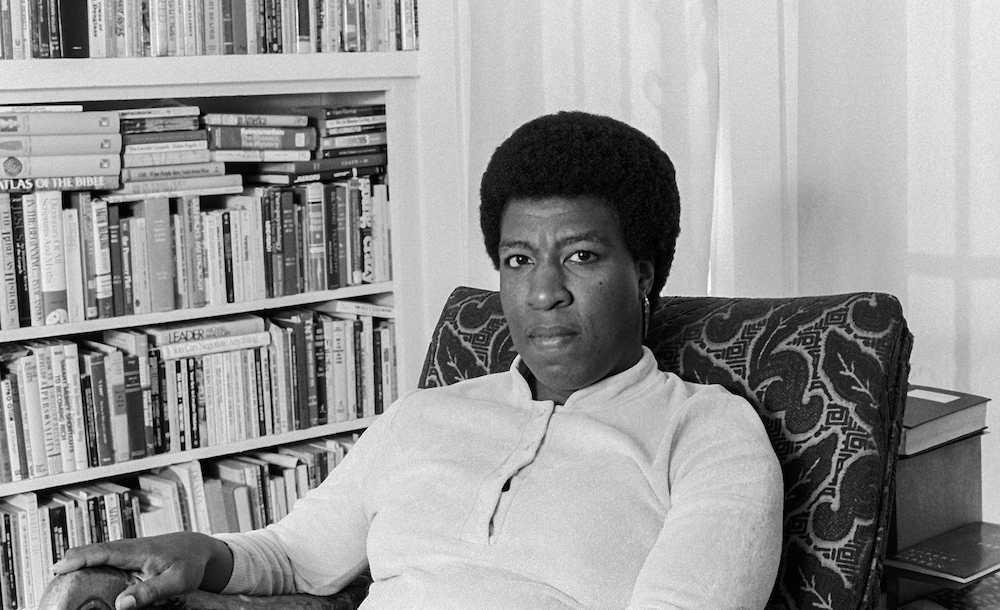

The writing and life of Octavia E. Butler is a throughline in the show’s narrative. Butler not only explored radical imagination in her work, she lived it. She used affirmations to keep her goals in focus, writing promises to herself in large letters and colored inks and taping them above her desk. Realizing that most science fiction didn’t explore the human variations of race and gender, Butler focused on helping to change this. Her writing straddles science and speculative fiction. She created worlds which reimagined gender, history, and science. Her narratives placed Black womxn and gender queer characters as central figures who founded religions, species, and new worlds. Although Butler never identified as an Afrofuturist, her novels speak to the core of the Afrofuturist genre wherein Blackness, space, and time invite us to imagine what could be and where Black womxn’s visions change the very fabric of the world. These ideas are embedded in the exhibition’s thesis.

How did the political climate and revolutionary moments we’ve been living through affect your process?

When 2020 started to resemble the stories of Octavia E. Butler, this is when the ideas in the show felt “of the time” for me. In her Parable series, which is set in 2020–2040, civilization has largely collapsed due to devastating wealth inequality, climate change, racial unrest, global disease, and the torment of a president whose slogan is, “Make America Great Again.” Butler famously said, “I don’t predict the future. All I do is look around at the problems we are neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters.”

I actually wrote the proposal for this project in late 2018. As a non-Black curator, it was important to center the voices of the Black creatives on the project over mine. I saw myself more as a facilitator and approached it from a place of curiosity and openness. Knowing that I didn’t have a Black lived experience, I trusted the people on the project and the process that unfolded. My role was to find the connective threads and follow the leads of the artists, community collaborators, and the Consulting Curator, Essence Harden.

How did you conceptualize the mix of genres?

Working with the team, we had to settle on a number of guiding principles to ground ourselves in the work. We choose Black feminism, self-determination, Black joy, and the mundane. Much of Afrofuturism is fantastical and otherworldly, and, as a counterpoint, mundane Afrofuturism rejoices in the pleasures of the everyday. The show definitely has its dazzling moments, but we wanted to keep it grounded in the elements of Afrofuturism that honor and value ordinary, everyday Black life.

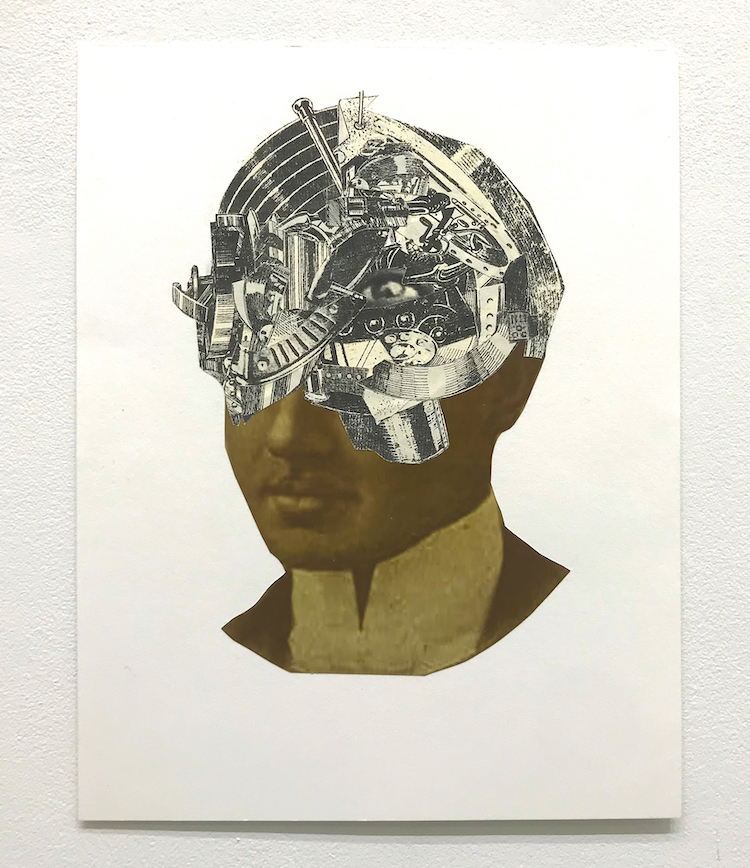

Describe the original artwork by Rashaad Newsome, and how his work best conveyed the essence of this exhibition.

When I saw Rashaad Newsome’s show To Be Real, at Fort Mason in February 2020, I was thrilled to find out he wanted to participate in our exhibition. I asked him if we could include pieces from that presentation along with his fantastic wallpaper. We were moving ahead with this plan when the pandemic hit and we all went into shelter in place. While working in his studio in Oakland, the uprisings inspired Rashaad to make the powerful collage, titled Parenting While Black, 2020, which we ultimately came to acquire for our collection.

What’s an example of a piece in the show from the Museum's collection that enhances and underscores your themes?

The quilt in the Earthseed section by Arbie Williams is a part of the OMCA collection. I think the subtlety of this addition to the show might be overlooked. I wanted something in this section to bring the project back to earth, to ground it in home and mundane life. To me, a quilt epitomizes mundane Afrofuturism. Quilt-making draws from Southern Black American traditions and often commemorates events that symbolize abundant futures, such as marriages, births, and new homes. Quilts represent the sustenance of Black people, as they literally keep people warm and cared for.

Tell us more about your team and collaborative process.

One of the best parts of building this exhibition was all of the collaborations that went into it. The earliest conversations started with former OMCA Senior Curator of Art René de Guzman. We spent about eight months identifying Black artists, curators, scholars, and community members who were exploring the themes of Afrofuturism. From these conversations, Essence Harden came highly recommended to us as a Consulting Curator. We invited her to join the team because of her work in the Bay Area and the LA art scenes and because of the connection to her hometown of Oakland. She is also a PhD candidate in the African American Studies department at Berkeley. It was this combination of scholarship and personal connection that made her a critical thought partner. We eventually came to work with over 50 contributors on the show.

A serendipitous collaboration was with Wakanda Dream Lab (WDL). WDL are an Afrofuturist, fan-driven collective that bridges Black Fandom and the Movement for Black Liberation. They produce immersive storytelling experiences through their anthology series inspired by Black Panther’s Wakanda. They knew we were going to have a costume from the movie Black Panther in the show, but they didn’t know which one. And we didn’t know what type of work they were going to want to display in their installation.

When I reached out to Marvel to ask them if we could display one of the original costumes from the Black Panther movie, it was important for me that we showcase a Dora Milaje costume, instead of the Black Panther costume, in order to further the Black feminist narrative. As we began our conversations with WDL, we discovered the work they wanted to include in the show also showcased the Dora Milaje. Artist Amir Khadar’s print, which is displayed in the show, is titled Descendants of the Dora Milaje. The excerpt included in the installation is from the anthology, Re-imagining Gender in Wakanda and was written by Innocent Immaculate Acan. It follows a scene where Okaba has disobeyed her tribe’s rules to join the men in combat against an enemy. She meets Okoye, leader of the Dora Milaje, who praises her rebellion instead of frowning upon it.

This coincidence provided us with a nice opportunity to connect the costume display to the WDL installation in a playful and unexpected way.

What are some of the common threads you noticed in all the work, regardless of genre?

Black people claiming their rightful place, shaping narratives, and creating innovative and sublime experiences.

Mothership: Voyage Into Afrofuturism is on view until February 27, 2022.