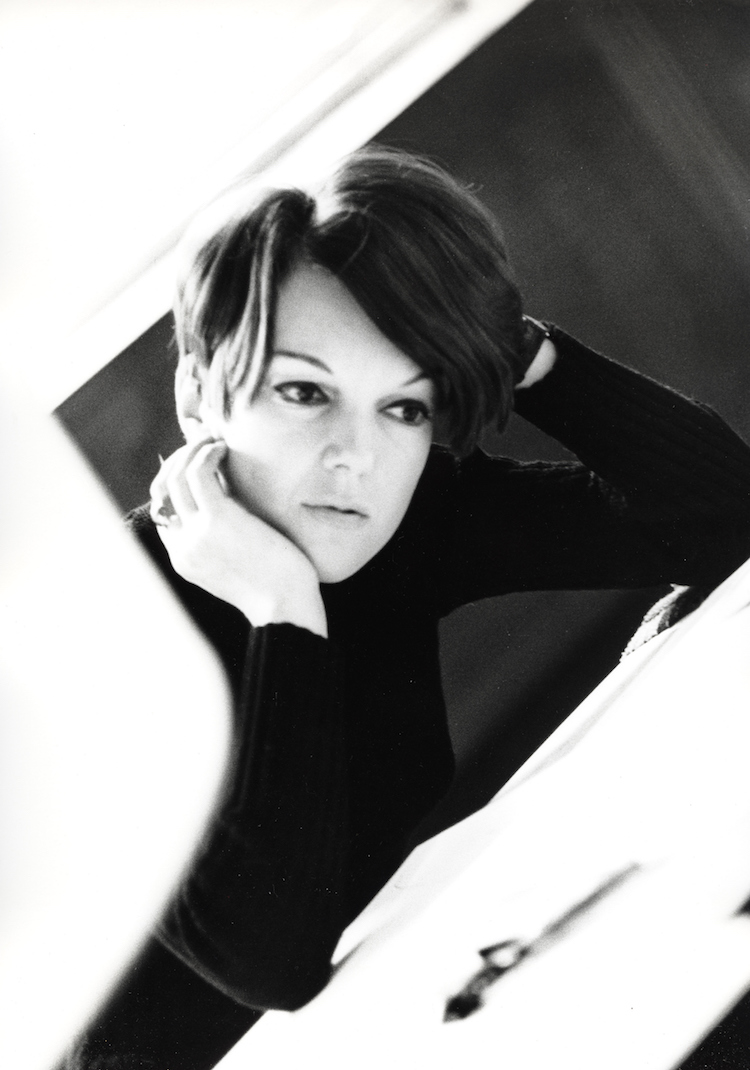

Thinking back to how Mary Quant unsheathed bodies from beige hosiery and long skirts, I’ll go out on an unshackled limb to say she almost single-handedly brought freedom of movement and expression to fashion, as in the clothes we wear to run for the train or hop out of a truck. Who better than London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, holder of the largest public collection of Dame Mary Quant’s garments, to mount such an exhibit. Co-curator of the show, Stephanie Wood, fills us in on the designer who declared, “Good taste is death. Vulgarity is life.”

Gwynned Vitello: Can you describe the social and economic scene in London when Mary Quant emerged? This so-called Fashion Quake couldn’t have happened anywhere else, right?

Stephanie Wood: Mary Quant came out of gloomy, post-war Britain, with rationing still in place until 1954, and in many ways, her designs are a reaction against the drabness and austerity of the time. Her colorful and fun garments reflected the optimism of that period, with growing affluence and social mobility of young people benefiting from further education and higher wages. She revolutionized style for women, harnessing youth, street style and mass production and ultimately defined the spirit of the swinging ’60s.

What would you say she took away from art school, besides meeting her husband, who seemed to be a great influence?

As a teenager, Quant longed to study fashion design, but her parent insisted she follow them into teaching, which was a more conventional career choice for a woman. As a compromise, she trained as an art teacher at Goldsmiths College. Attending art school had a profound impact on the course of her life; not only because she met her husband—trumpet-playing aristocratic Alexander Plunkett Greene, but because art school exposed her to a network of free-thinking artists, designers and bohemians who shared her vision of building a progressive, new identity for post-war Britain.

Would you agree that humor and having fun guided her designs? What else about Mary’s personality had an effect on her work?

Humor and fun played a huge part in Quant’s designs and ultimate success. Her garments were distinctive and playful, often giving witty and irreverent names such as Banana Split, Hot Dog, Snob and Booby Traps (for her single triangle-shaped bras.) A key part of her success came from her vision to see fashion as a means of communicating new attitudes, ideas and change for women. She was also defiant and daring, pushing the boundaries of what was accessible for women to wear, and liberating young women from the stifling rules and regulations and conformity of her mother’s generation.

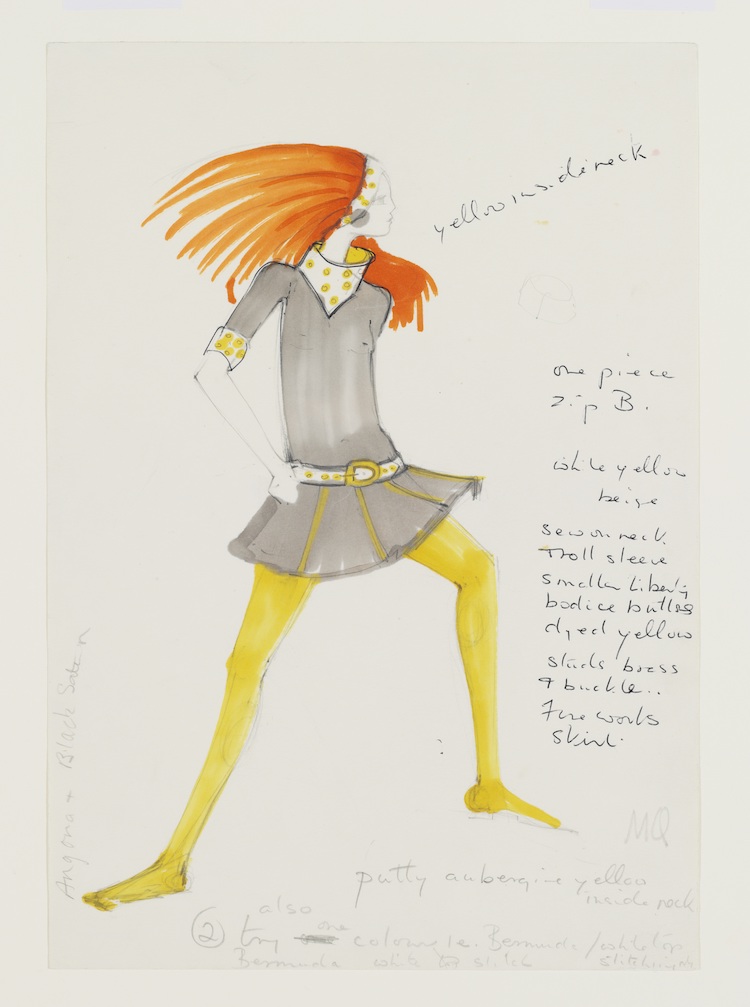

Her creativity enabled her to be a prolific designer, churning out hundreds of sketches each year using the caran d’ache watercolor pencils she loved so much. Finally, Quant’s steely determination enabled her to forge a trailblazing career..

We’re talking about a different time, but I was surprised to read about her relationship with Butterick patterns. I think that also speaks to a sort of democratic approach to fashion.

Mary Quant’s approach to fashion was egalitarian and is reflected in her move into mass-production in 1963 with the Ginger Group line, which made her designs much more affordable for working women. The whole point of fashion is to make fashionable clothes available to everyone. Her range of Butterick homes dressmaking patterns brought some of her most iconic designs within reach of all Quant fans for the cost of purchasing a Vogue magazine, and her hugely successful cosmetics line, introduced in 1966, established her as the godmother of accessible designer fashion for all.

Did she actually start in retail before design? Did her store Bazaar pre-date Mary Quant designs?

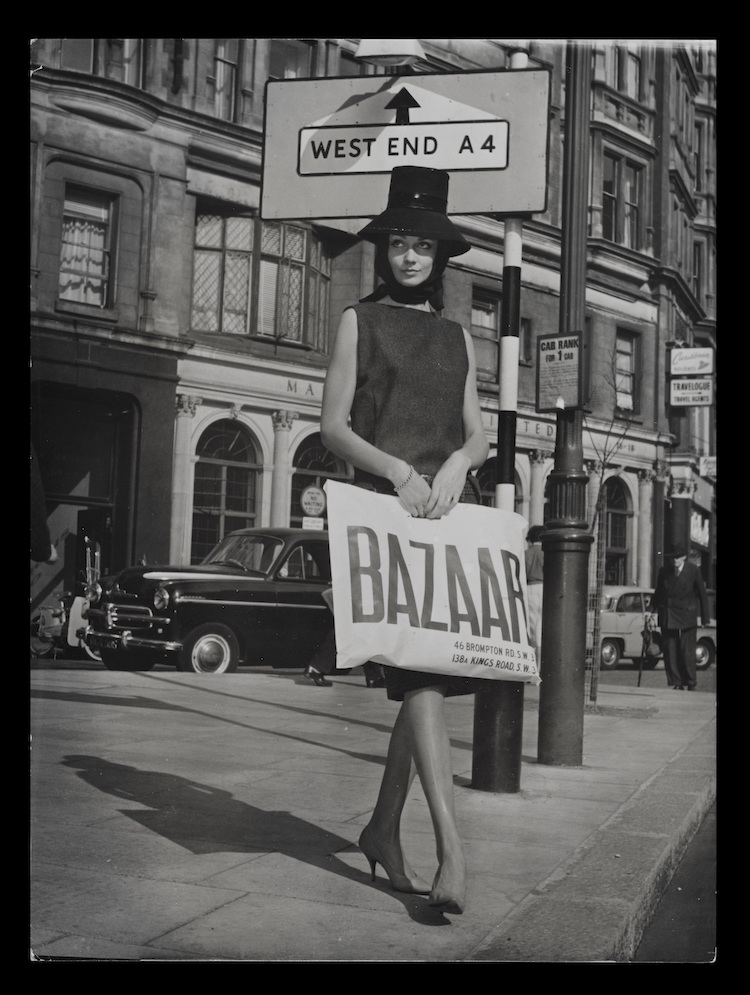

After leaving Goldsmith’s, Quant’s first job was trimming hats at Erik’s, a couture milliner in Mayfair. By 1955, she opened her experimental first boutique, Bazaar, on King’s Road in London. Initially, her role was to comb wholesale warehouses and art schools to source quirky garments and jewelry for the shop. However, she swiftly grew tired of that limited range of garments available, and so began to design herself in 1956, studying at night school. Once she began designing, her garments were so popular that the stock would sell out swiftly, and so the early days of Bazaar were defined as a hand-to-mouth operation, with Quant making dresses in her bedsit in the evening to replenish stock for the next day.

Is it a stretch to say that she was one of the first to transform shopping from a purchase transaction to an actual experience, and maybe one of the first to introduce fast retail?

Bazaar was a forerunner of the explosion of boutique shops, which happened in the late 1950s and ’60s in London. Through Bazaar, Quant transformed the retail experience at a time when shopping was a relatively formal experience. Through music, drinks, and continually changing stock, she created an almost cultural hub, more akin to a club than a shop, which the Chelsea set flocked to. In 1958, Quant took on the fashion giants of Knightsbridge, brazenly opening her second Bazaar shop opposite Harrods itself.

Although Quant was a great advocate of affordable fashion for all, her garments would certainly not be considered fast fashion. The quantities being produced were incredibly small compared to fashion today. Quant’s ethos was to offer women choice and a range o well considered garments with mix-and-match potential, not continually produce new designs in response to fashion trends.

Specifically, she made mannequins into visual art, and her models more like actors than just coat racks, right?

Mary Quant pioneered a new approach to window display that we take for granted in retail today. She specifically commissioned dynamic mannequins from Rootstein in the gawky poses of the day and went as far as modeling them on Jean Shrimpton’s “long, lean legs.” These were far removed from the conventional shop window mannequins of the 1950s and ’60s, and she would artfully arrange them in the window, walking lobsters on leads or suspended from the ceiling.

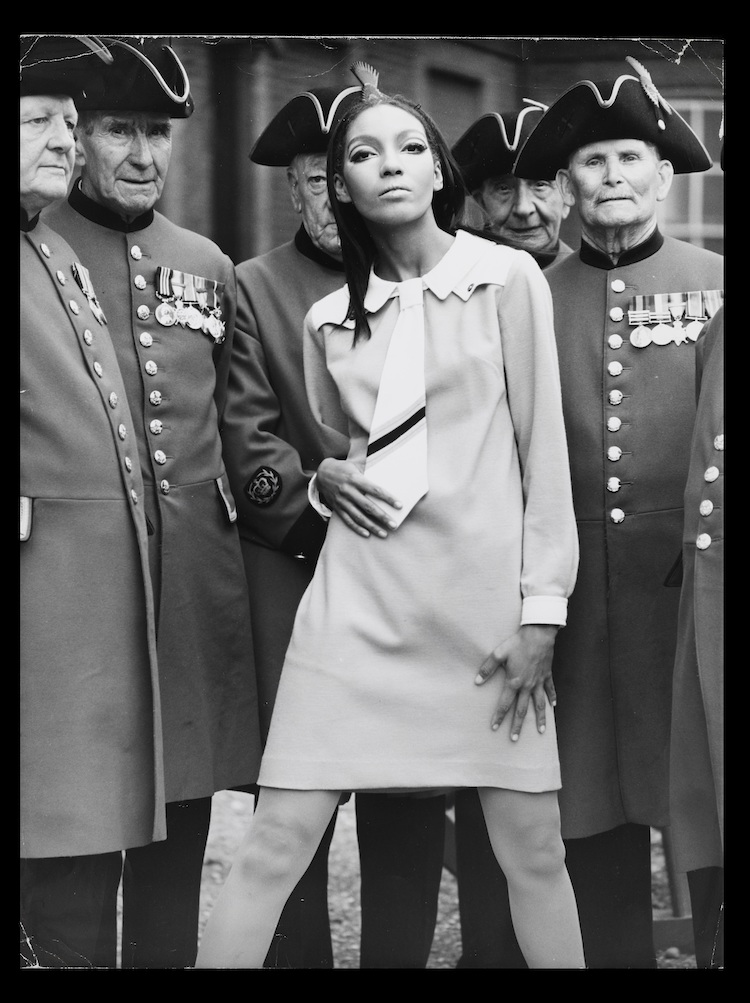

Equally, Quant’s fashion shows were a far cry from the established salon-style presentations as followed by the leading designers of the time. She preferred to use photographic rather than salon models because they swung rather than paraded down the catwalk, adopting dramatic poses en route. These shows were characterized y fun, energy, high-speed and movement, with models dancing wildly to the “hot jazz” that Quant loved so much.

In that vein, how are the designs displayed and arranged in this show?

The design concept for the show is themed around the boutiques and the street, and we have several cases in the exhibition that have been arranged to look like the Bazaar shop windows complete with specifically commissioned dynamic, mannequins similar to the ones Quant used, in addition to props and a mannequin walking a lobster on a lead!

Let’s talk about the clothes more specifically. Is it true that travel by scooter played a part in her designs?

Freedom of movement certainly played a big part in Mary Quant’s designs. She wanted to create garments that could be worn by real women as a tool to complete life, so they could run for a bus, dance, and retain their precious freedom. Her designs were far removed from the often restrictive, corseted garments and narrow, hobbled skirts of the 1950s.

Her choice of materials was really innovative and she was the first to incorporate PVC in clothing. What were some favorite fabrics and design elements she used that emblemized freedom and independence? How did she view color?

From the beginning of Quant’s career, she experimented with new and unconventional materials. Her earliest designs used men’s suiting fabric for womenswear to playfully change traditional gender norms in fashion. In 1963, she launched her “Wet Collection,” experimenting with a new material, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) which captured the ’60s fascination with technology and the space age. Quant declared that she wa “bewitched with this super-shiny, man-made stuff and its shrieking colors… its glimmering liquorice black, white and ginger.”

As the 1960s progressed, she explored new fabrics which were available, such as nylon and jersey. Quant’s discovery of a new type of heat-bonded wool jersey was a revelation for her. It had been previously used in underwear and for rugby and football, and its smooth, fluid qualities were perfect for Quant’s signature sporty mini-dresses, which she produced prolifically in a rainbow of the brightest, deepest colors. She was always striving to find innovative new materials that could revolutionize the way she designed and provide increased comfort and ease for women.

I’d like to hear more about the V&A’s call out for clothes. How big was this effort? It sounds like that was a lot of fun, and there must have been stories with each piece.

Back in June, 2018, we launched the #WeWantQuant campaign, a public call-out to locate rare and missing garments by Quant, and collect personal stories and memories from real people who wore her clothes; and with over 800 replies, to date, the response has been overwhelming. These garments and the life stories of the women who wore them show how modern Quant’s designs were. So many people have treasured their Mary Quant dresses because they represented freedom and a special time in their lives. It’s a testament to how much Quant meant to women that they kept them for so many years.

Many came forward with Quant clothing made for special occasions. We uncovered, for example, a very early, boldly printed top bought by a research scientist to meet her geologist fiancé returning from a trip to Antarctica, a PVC raincoat worn and lovingly kept by two generations of women in the same family, underscoring the longevity of Mary’s designs. We’re also featuring a dress homemade from one of her dressmaking patterns for the wearer’s 21st birthday.

Mary Quant’s work is on view now at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum through February 16, 2020.