Cassi Namoda

The Sense of Saudade

Interview by Kristin Farr // Portrait by Isaac Brest

Cassi Namoda is a soothsaying painter who explores the duality of Mozambique’s post-colonial identity. Storytelling through metaphorical female protagonists, she distills history, bringing emotional strength to the forefront. Namoda is a wise soul, a magnetic luminary who flies hand-painted kites on the beach and possesses an innate understanding of herbal alchemy. Saudade is the name of her artist edition tea project, and a Portuguese sentiment essential to Africa’s Lusophone perspective; it’s the word for an indescribable longing, and an undercurrent in the artist’s contemplative, allegorical work. She interprets history with empathy, which serves as an enlightened catalyst for understanding.

Kristin Farr: How are you?

Cassi Namoda: Summer in Long Island; I can’t complain. I’ve been in the studio prepping for shows, and I’ve taken up a new hobby of surfing, which has been a nice way to move my body and be out in the water.

I was admiring your painting, Maria Outside Bar Mundo, and wondering about the figures.

I look at older paintings a lot, sometimes in a more literal way, and I apply them to a more personal context, in terms of what I’ve been exploring with post-colonial Mozambique. I have an old Shaker box full of all these archival images, and one of them is Edvard Munch’s lithograph from 1895, The Alley. So, I’m translating this lithograph into a painting, and that’s the gist of how I work.

Any painter should access the history of painting and those who came before them, and others have always done the same before me. I started looking at van Gogh’s work, and he was making French rural paintings when he was checked into the St. Paul asylum. He was looking at Millet because he needed material to paint from in order to keep himself occupied. Since he couldn’t do much research, he thought, why not just make these paintings that I love?

There’s a van Gogh painting, Rest from Work (After Millet), with two figures on a haystack. His use of color and gestural strokes helped educate me, since I don’t have a formal background in painting. I can find amazing material in bookshops about the history of painting and how artists have been inspired by culture—like Giacometti, with his sculptures that have a primitive essence, or Picasso with the masks. Painting is this assemblage of ideas that come through me, and I lay them out in a way where the narrative is honest to what I want to portray.

I made a painting that has this old, broken-down church from the fifteenth century, a Byzantine-style church in Northern Mozambique, where my mother is from. I took that essence of architecture and place—and I always think about landscape. We’re looking at so much figurative painting right now, and in that excess, I feel there’s almost a duty to step outside of that. That’s why someone like Millet is interesting for me, because he’s looking at movement in a rural context, and the faces aren’t really that important—it’s just washer women, or people tending to the field. I like these different concepts of living that can show up in painting.

My painting with the church has an abstracted background with pale greens, and then these prawns walking into the church. The prawns are symbolic of the appetites of the place my family is from, it’s a very particular dish you’ll find there, so the prawns walking into a church are these quite surreal elements. For lack of a better way to say this, it’s keeping things interesting and authentic, and in the world of individualism. That’s what I’m striving for—and then the evolution of being, for whatever that means, stylistically, or through process.

Growing up, I’ve always had to adapt, and it’s given me an attribute where I’m able to connect dots. I might be looking at this Munch painting, and then I’ll find it’s bizarrely similar to Ricardo Rangel’s work. He’s a photographer from Mozambique, and his work was mostly documenting downtown Maputo. His images intersect with the historical paintings, and I’m looking at the vulnerability of the figure.

And collapsing time through multiple references. Do you think about timelessness?

After my show at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, a lot of comments I received were from people who felt they didn’t know who was behind the paintings. There’s an ambiguity with time, but, ultimately, I don’t know if that matters. If I’m connecting with The Alley, and Edvard Munch made it, there’s some sort of human experience that underlies the work, and that’s universal. It’s just living.

Not being able to tell who’s behind the paintings sounds like success in that they’re universally read.

That’s what it’s about. There’s no ego, it’s just me wanting to put an essence of a picture out there, something someone can ruminate over, consider, or relate to in a visceral human experience, whether it be uncomfortable or confusing. Sometimes it’s just a nuance.

I’ve always been told that I’m an old soul. I don’t really know what that means, but the weight of the paintings feels current to me. Sometimes the work feels like it’s from a different time, and it truly is also a question of time. Maybe I’m stuck in ’60s or ’70s rural Africa in my spiritual self. I think about the authenticity behind the characters, and the dignity behind them.

Those decades preceding the time we’re born have an appealing or nostalgic pull because their influence lingers.

Exactly. We’re looking at photos of our parents in their golden time, maybe their early twenties, and it feels free and inspiring—that time in culture all over the world. A lot of my mother’s clothing was handmade by my grandmother, these amazing bellbottoms and workwear tops, and these interesting jewelry pieces… nothing ornate, maybe just ivory shells around her neck, very simple. All of that detail translates to what I’m considering when I think about personhood.

The prawn painting is a gem.

I’m working on seven paintings for a show in LA, and they connect systematically with a lot of amethyst, orange, bright greens. And I’ve been painting the circular moon a lot. It was more dull and Mars-like in previous paintings, and now it’s bright. It was time for it to become a glowing, luminescent thing in the sky.

There’s a mother in the foreground of the prawn painting, she’s dressed in a bright orange, just like the woman in the Bar Mundo painting. There’s something reviving about the color orange, like a life force. A friend of mine said I was a color savant or guru.

That must be true, as evidenced in your recent show of small works.

I had been in Kenya and South Africa, and I was going to continue traveling and then make a project in Copenhagen, but then the covid happened. So I came back to Long Island, knowing things were different, and I would have free time, in a way.

I wanted to challenge the notion of currency being so important, especially in the art world. The show was at Nina Johnson’s gallery in Miami, who knew me early on when I was making works on paper and small paintings. There’s something vulnerable and tender about small works. I tend to keep my smaller paintings, or give them to really close friends. I felt we needed more small paintings in the world.

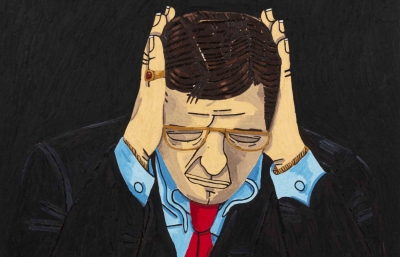

That show, Dog meat, cat meat, God-knows-what meat, was an amalgamation of take-it-as-you-like paintings, with this idea that we’re entering unprecedented times, but without being obvious. I’m pulling it back. Can we question how we’re living? Can we question humanity? There’s a painting of a girl on crutches, in a field, with balloons in the background—again, the notion of duality.

In the London show, I was connecting the idea of family and friends, so I had paintings with conjoined twins, and the marriage theme on Maputo Bay. In Miami, the show was more sporadic, with room to explore randomized images, like the Lamu police officer—I thought about the way the local officials dressed, and he was eating a rose. I called it A moment of bliss (in the midst of confusion). My work can always relate to living and life, and the smaller paintings were about expecting the unexpected. And the assumption that bigger is better is not always true. To paint life is to keep an open mind.

When I’m making paintings that are four inches and fit in my palm, the more detail, the better. People say it must be hard to make big paintings, and I say it’s just as hard to make a small one. My first show in LA were works on paper, and people said, “These are amazing. What if they were bigger?” And I thought, wait, is there something wrong with intimacy?

It’s a bit like saying, “You should make these less accessible.”

I’m always thinking about that. In Miami, I was out on the streets trying to invite people of color to my show. They’d ask if it cost money, and I would tell them it’s free to look at the artwork in the gallery. I’m always thinking about access, and that’s partly why I have my tea project.

Tell me about the tea.

It’s something I wanted to do for a long time. I settled in Maputo for a couple years in my early twenties, and I went to my grandmother’s hometown, Gurué, several hours north. I saw the most beautiful tea plantations. In Mozambique, post-Portuguese colonization, tea was seen as a rural, working-man’s beverage. Anyone of stature would drink an espresso if one needed the caffeine.

In Gurué, they still drank black tea, and I was amazed by the quality and scent of the leaves. I sent some to my sister, who worked in tea, and discovered it was a beautiful Ceylonese with unique attributes. I thought it would be amazing to share this tea from Gurué in a really romantic way, so I found a plantation to work with. Post-Portuguese imperialism, the tea plantations were left with no ownership, and essentially degraded. There was a civil war for years, which left most of the plantations burned down, but the one I found was left behind, and later won in a lottery by tea people from Kenya. They revived it and practiced ethical habits with this special leaf.

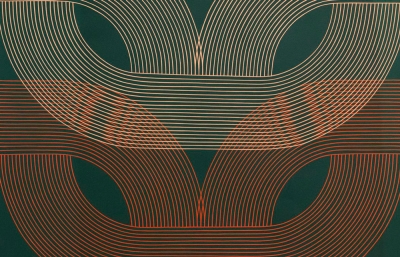

I thought about the aesthetic of the packaging, and making it accessible, like a print. It’s my way of making an artist’s edition with tea. I made two artworks when I was in Spain, Maria’s Tears, which is Maria crying into a small tea cup, and Monkeys Laughing, thinking about the jovial quality monkeys have when they cackle. One notion fit with the afternoon tea, and the other with the morning tea. The packaging design references Mozambique architecture, which is essentially the identity of the towns there. That Deco aesthetic influenced the fonts and colors of the packaging, which we letterpressed. It was a beautiful coming-together of ideas, and it worked really smoothly.

And please explain Saudade.

Saudade is a Portuguese word that’s hard to translate. The Japanese have a word that’s very similar. It’s a longing and missing of a place or time that one can’t necessarily put their finger on; exploring the wants of emotion. Maybe we don’t have a word for every emotion that we feel, but we can identify it.

In Lusophone, it’s a common term that wraps up all together, in a loose way, what it is to miss something. That terminology was created quite early in the Vasco da Gama Portuguese discovery of “new worlds.” Wives would stand along the water as their husbands took off and sing this folkloric music called Morna. It’s still common and beautifully expressive, and, in essence, there’s a culture created from the word Saudade, in terms of daily life and connecting to this common feeling. There’s something meditative about it, without being happy or sad.

What other aspects of Lusophone culture do you honor?

I lived in many different countries in Africa. The way I can describe it, in a sense, is that there’s no way around it in your daily life and thinking. When I reminisce about a place, I can feel the assemblages of what colonialism did to the country. When living in Uganda, you can feel the essence of British culture, aesthetic and habits, and the idea of being a “good Christian.” When I’ve lived in Francophone Africa, there’s an interesting mix, a sense of wanting to adapt to being French, or connecting with the idea of a French colony, and the influence within Boulangeries and the way people dress.

In Mozambique or Angola, there’s a very stoic approach. Atheism tends to be common, in terms of spirituality, and there’s some animist belief, an amalgamation of habits, and then this really Brutalist architecture. The Portuguese were experimenting and living out their wildest architecture or urban landscape dreams, for better or for worse.

In many ways, these countries of Lusophone Africa have not been so accessible in terms of the narrative told in the west. We know about Kenya, or South Africa, or Côte d'Ivoire, but Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique or Angola don’t pop up as often in the African narrative. There’s the idea of the danger of the single story. Stories of Nigeria and Ghana are widely told, but we need to be inclusive in terms of our narrative. In a way, it’s universal, but there’s a spirit from each place.

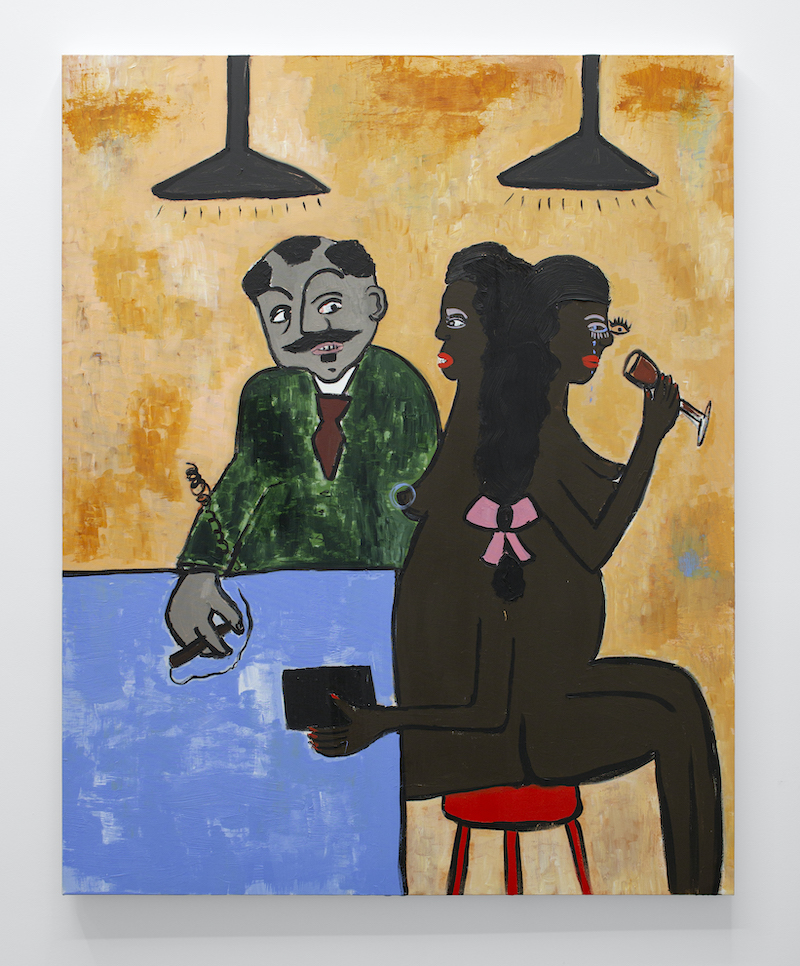

Who is Maria?

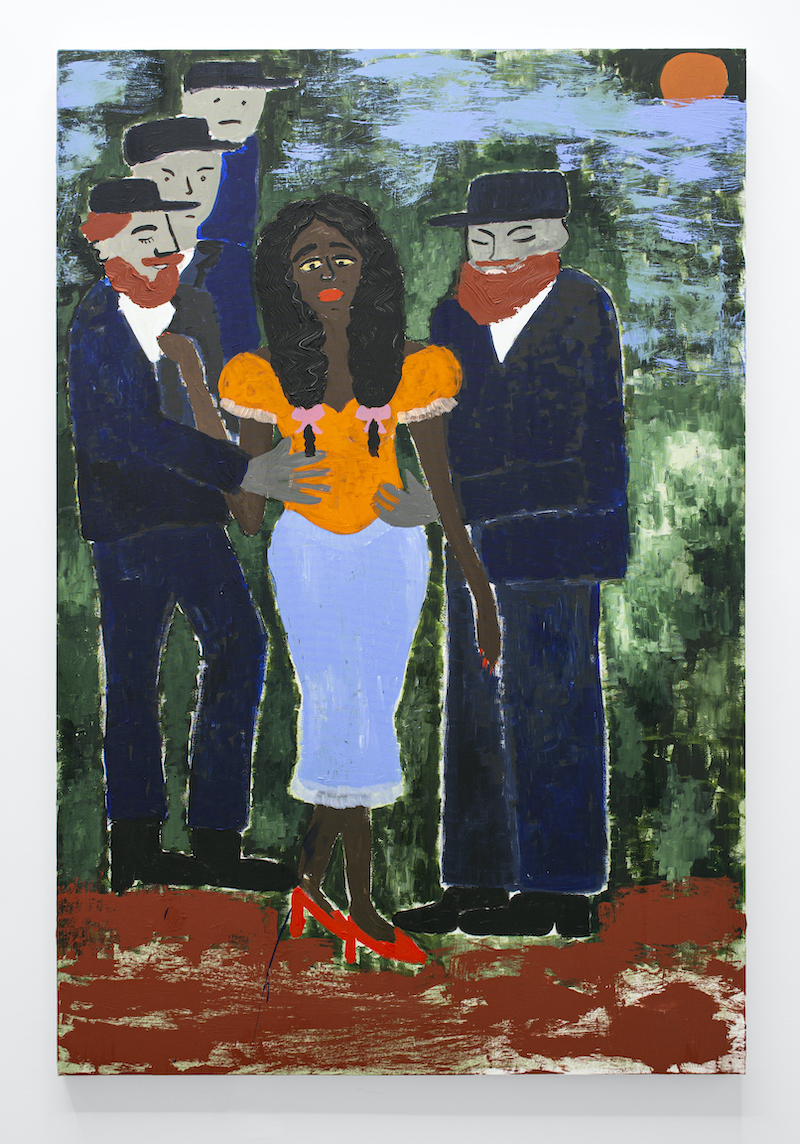

I find a way to do things narratively but less obviously, which is the more attractive route for me. Maria has become a very dimensional, dynamic parallel being that I’m able to metaphorically use as, essentially, the Mozambique story, or the Lusophone story. She’s sitting in a female figure, but at the same time… for instance, there’s another painting at Bar Mundo, with the conjoined Marias sitting next to a man in a green suit with a cigar. One Maria seems very happy with her company, and the other is having a glass of wine, almost like she’s hoping to disconnect from the space that she’s in. That, for me, is the best way to describe Africa today, or the aftermath of colonialism. It’s a multi-dimensional thing that we’re navigating. It’s the same level as human emotion. You’re constantly navigating and trying to understand. In a way, you’ve been taken advantage of, but maybe there’s something you enjoy about the resources. What makes Africa, as a continent, such an interesting story is that it’s one of the last untapped resources in the world, and it can go many different ways, in that respect.

When you think about Maria, as a woman, and FRELIMO, the Mozambique Liberation front, and the independence war—women had to be in attendance to the freedom struggle. They were not exempt. Women down south were in the fields fighting. There was one side of the story, where women were very strong assets. It didn’t matter if you were a man or a woman, you were part of the revolution, like the Black Panthers, who also had strong female figures. But then you had the women, kind of like Maria, who felt like, “What are we fighting for? I just want to marry a sailor and get out of here.”

That’s why I made the show, Bar Texas 1971, at the Library Street Collective. It was an idea about one night at this bar, and the trials and tribulations, or anxieties and drunkenness that exists in someone who is trying to navigate the best way possible. Northern Mozambique, for instance, had a lot of women who didn’t believe in the war. There was even a film about them, and how they were treated from FRELIMO because they didn’t want to fight in the guerra, so they were pinned down with nails through their clothes and stranded in the sun for hours because they were caught in downtown Mozambique.

In one way, I understand that everyone’s a part of the revolution if you want a free country, but I also believe in free will. That’s the thing about Maria that’s not often explored; she is a free person.

The conjoined twins in your paintings, analogous to post-colonial identity, also reference a true story.

Chrissie and Millie. They were born into slavery in the US and sold to a circus freak show. I was thinking about the black body, but also about what enfreakment means, and how science has given way to make us feel like anything seen as “other” through the Christian gaze is peculiar, from a conjoined twin or four-legged person, to a black-skinned person. I’m trying to challenge ideas that aren’t always right in terms of how otherness is viewed, and Chrissie and Millie are the perfect example.

They never owned their bodies because science was consistently on them. I learned that if they had an abscess, for example, hundreds of scientists would want to take photos and draw their intimate parts, when all they needed was a check-up. But they weren’t allowed to be women, and there have been studies showing that conjoined twins of European descent did not receive the same treatment. Chrissie and Millie were in these black bodies, so they were given away to science, ultimately.

My upcoming show at Goodman is called, To Live Long is to See Much, which is a Swahili proverb, but it’s also about the idea that we should be open. Right now, there’s a lot of educating, and with that comes a lot of political correctness. If you’re wrong, you’re getting cancelled, but we’re not really just listening. What is it to be a good human? If you’re open, you have sympathy and compassion, and maybe you listen before you speak—important attributes to have.

One last question: I heard you had a premonition that we’d be entering Biblical times in 2020, so I’m wondering if you know how this all turns out.

I’ve been at a loss, and I’m navigating my spiritual self through painting. In general, I’m positive, but also realistic. We must adhere to natural living, meaning get to your gardens, and if you don’t have one, find a way to put some pots on your windowsill or roof.

We have to make real change. We’ve already been through so much up to this date that we should be open for more, we should be less frightened of change, and open to living presently, in a way that’s meaningful in a global way. I’ve been fascinated by the locusts swarming all over Eastern Africa. That is something I see as a spiritual, Biblical sign. I look at these symbols. If that clears up, maybe we’ll clear up consciously as a society. I think we’re in a spiritual shift, and we might be in this for a couple years. We’re here for each other. We have to know that there are others like us.

Cassi Namoda has a new exhibition at François Ghebaly Gallery in Los Angeles, You’ll Be Old Too One Day. Life Isn’t Always Young and Sweet. It is on view through September 20, 2020. Her next exhibit, To Live Long is to See Much, opens November 19, 2020 at Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg.