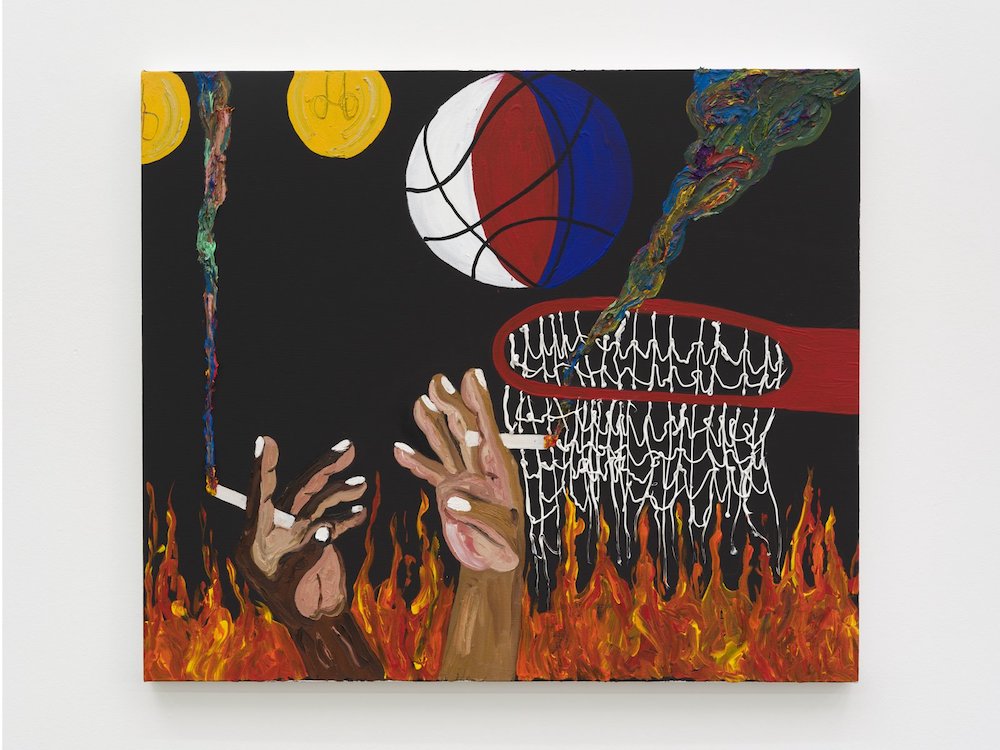

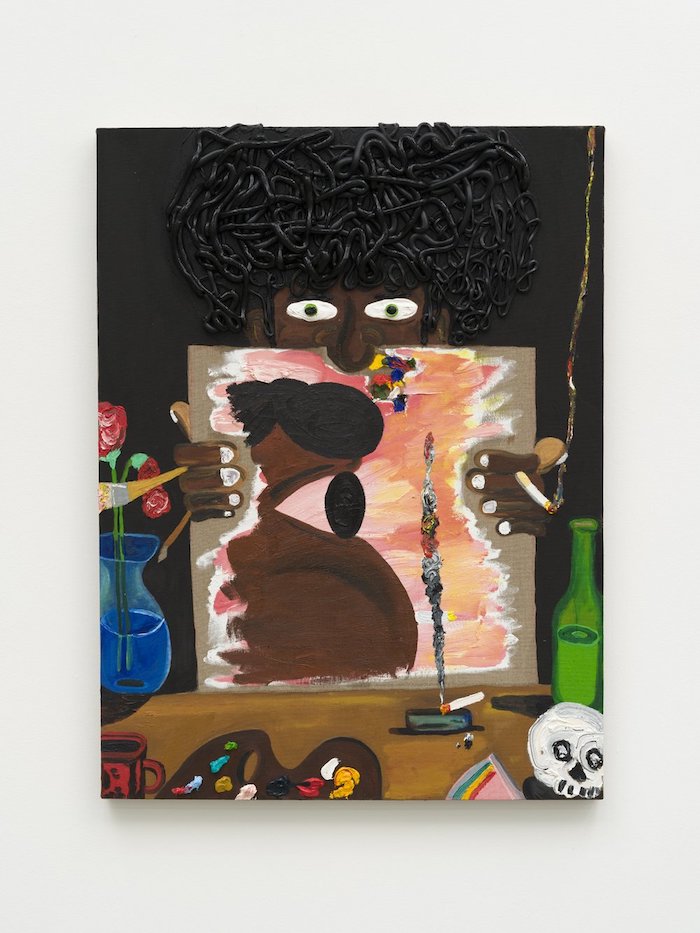

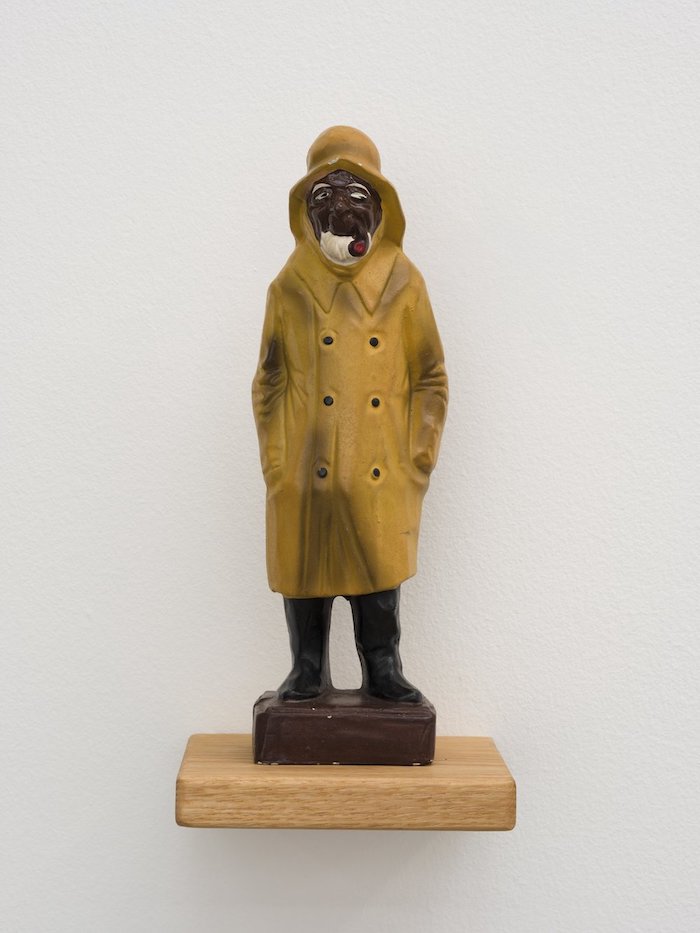

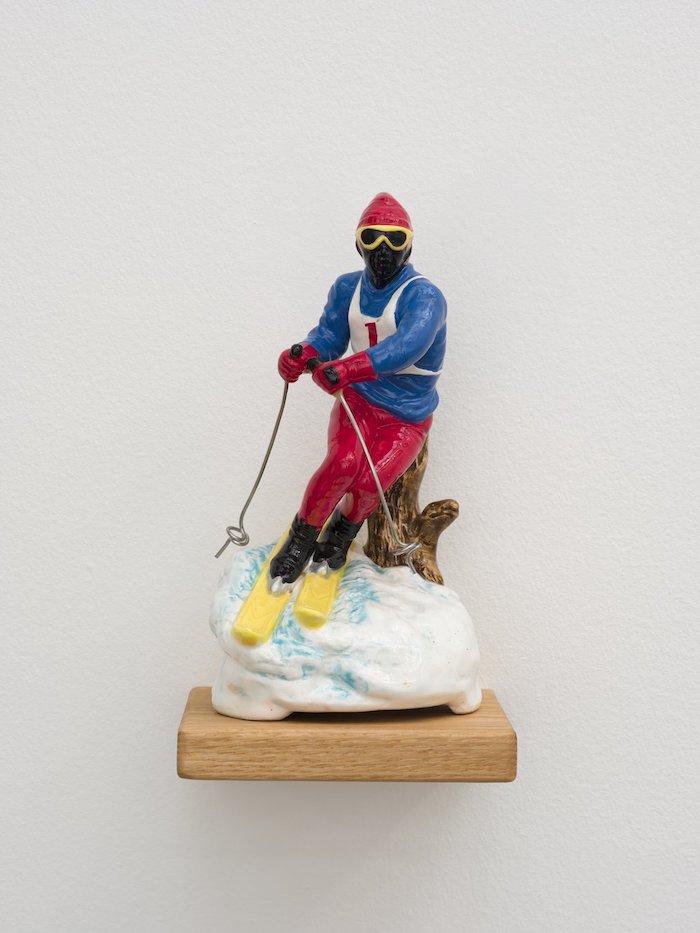

Even though Devin Troy Strother's newest exhibition, Undercover Brother, came down recently at the Pit LA, it continues to deserve attention. Interestingly enough and spoken about in art circles for a year now was the cancellation of Philip Guston's exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in 2020 and the debates that surrounded it. Guston has always been a bit of lightning rod; for his move from abstraction to figuration to his use of KKK figures in his works to his depictions of Nixon. Strother, always a burgeoning master of how linguistics and pop-culture imagery dominates our understanding of race, politics and, to a greater extent, art, has been creating works in ode to Guston for awhile now, but found purpose in this cancellation to dig further.

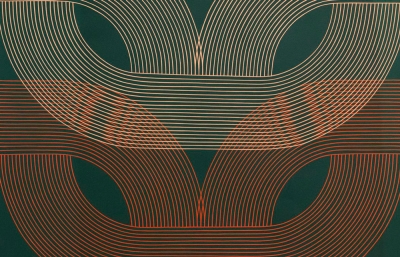

Strother has always been a personal favorite, with one of the highlights of my career was showcasing a neon of his at the Juxtapoz x Superflat exhibition I co-curated with Takashi Murakami at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2016-2017. The work, a nude woman with afro, hung over a doorway into another installation room, a claiming of entry in a way. His works are provocative, and here is that word again, with purpose. He has an incredible sense of taking the moment, the world has we see it now, and spin it with historical iconography and contemporary voice. His Guston works here and original as they are looking deeper at the controversy and influential and “an entry point back into figurative painting," as he puts it.

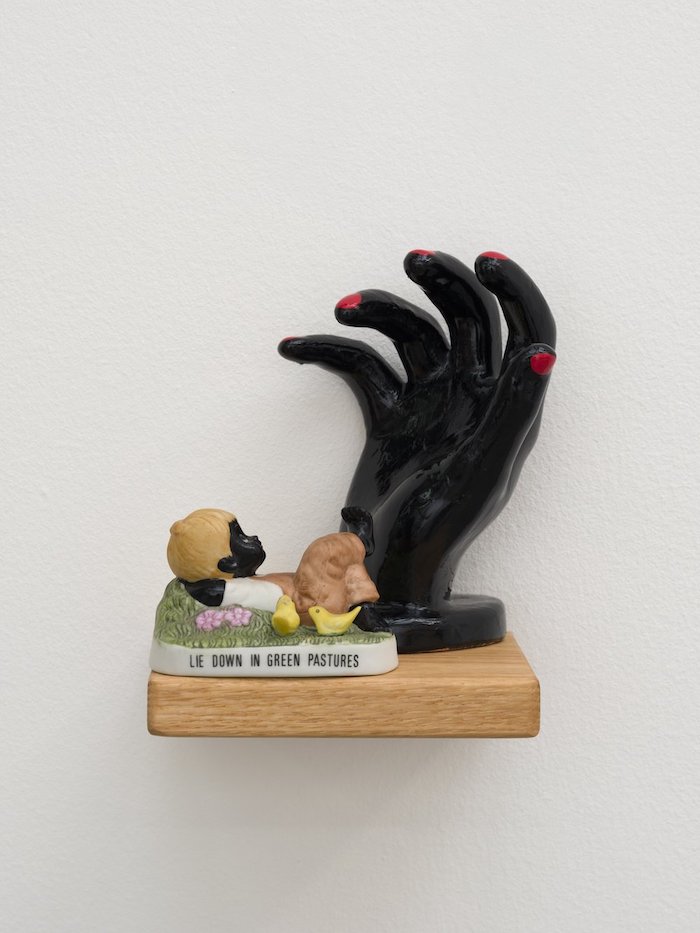

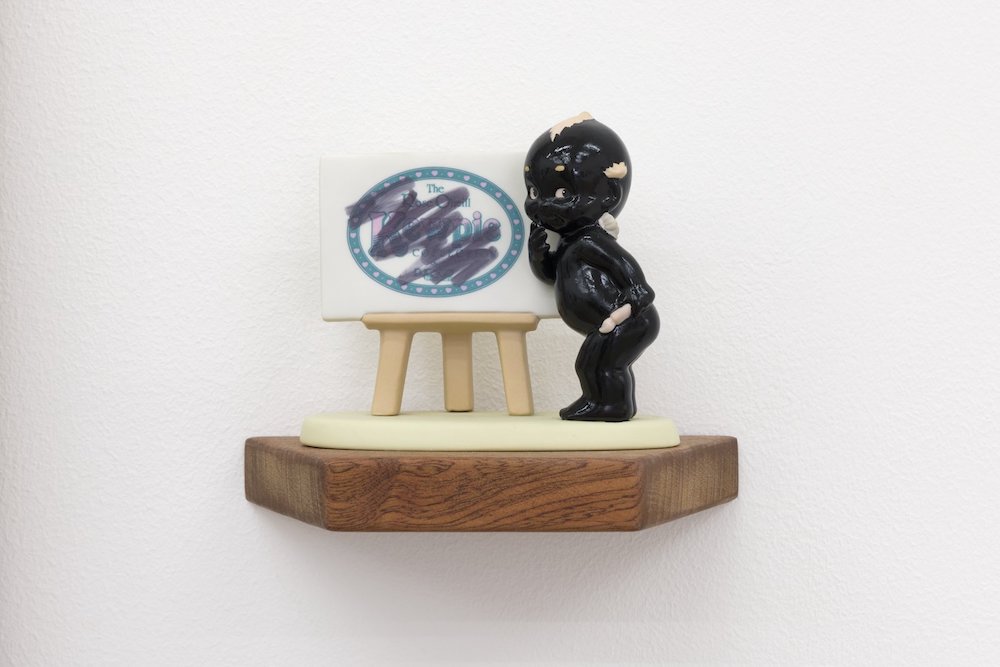

As the gallery points out, The paintings started as master copies, until Strother was compelled to “appropriate and adopt some of Guston’s themes and approaches from his show at Marlborough Gallery in the 1970’s.” Cancel culture and its restrictions on subjectivity disturbs and fascinates Strother; the cancellation of Guston’s recent show, for example, propelled his interest in “further putting myself in the other position. Guston tried to understand the mentality of hate…” Guston’s Klansmen resonate personally with Devin Troy Strother, whose mother’s side of the family left Lake Charles, Louisiana for Los Angeles in part, after harassment by the KKK. Like Nicole Eisenman and Dana Schutz, Strother continues to populate his artworks with conflicted figures, to create captivating formal and subjective problems through heavy referencing. While Strother may not crank out Guston variants forevermore, the paradoxical realization that on one hand nobody can own styles or aesthetics, while on the other, oppressed populations use reclamation, reinvention, and empowerment as sources of pride and survival will certainly continue as a central motif in Devin Troy Strother’s art.

That is a key here; this idea of reclamation, reinvention, and empowerment that we often miss when we talk about why an artist may channel a precursor or legend of a particular genre. As Guston has become more and more of a source of inspiration for figurative painters, Strother is taking the source and deep American cultural context of Guston's work and creating a new series of icons. It's powerful, it's irreverent at times, and it's one of the best shows of 2021. —Evan Pricco