Eva Presenhuber is delighted to present Cotton Mouth, an exhibition of new works by the American artist Tschabalala Self. Cotton Mouth is Self’s debut solo exhibition with Eva Presenhuber and features paintings, drawings, sculpture, and an audio piece.

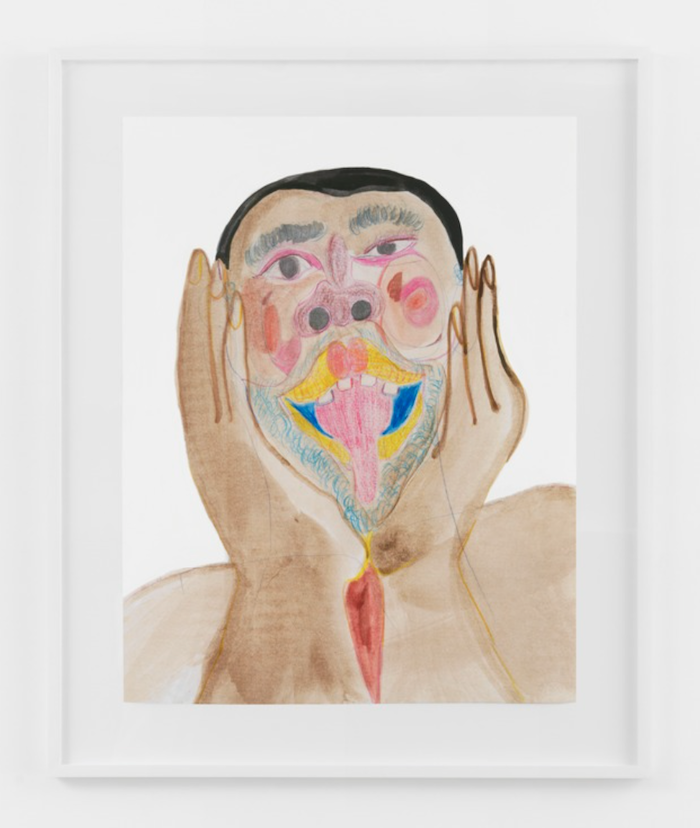

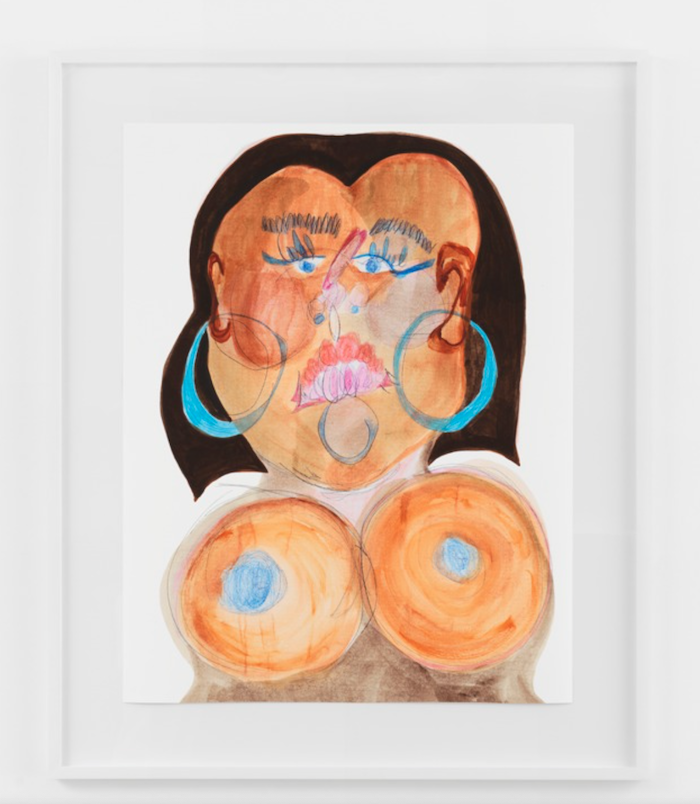

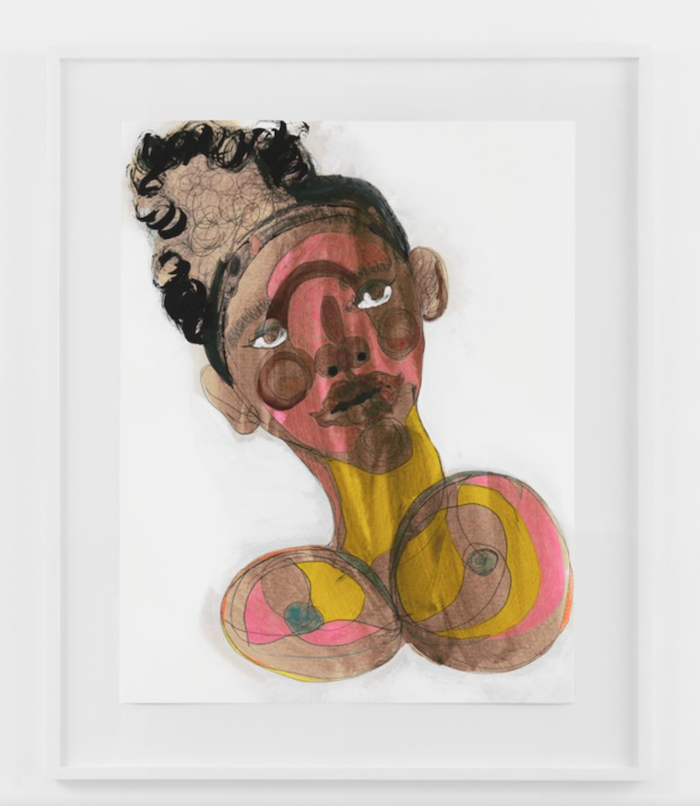

In process and presentation, Tschabalala Self’s work explores the agency involved in myth creation and the psychological and emotional effects of projected fantasy. Self has sustained a practice wholly concerned with Black life and embodiment, with an intended audience from within that same community. In a flurry of stitches, Self assembles fully formed characters who, individually and situationally, hold power over their self-presentation and external perception. A power frequently denied to Black American people in their daily lives.

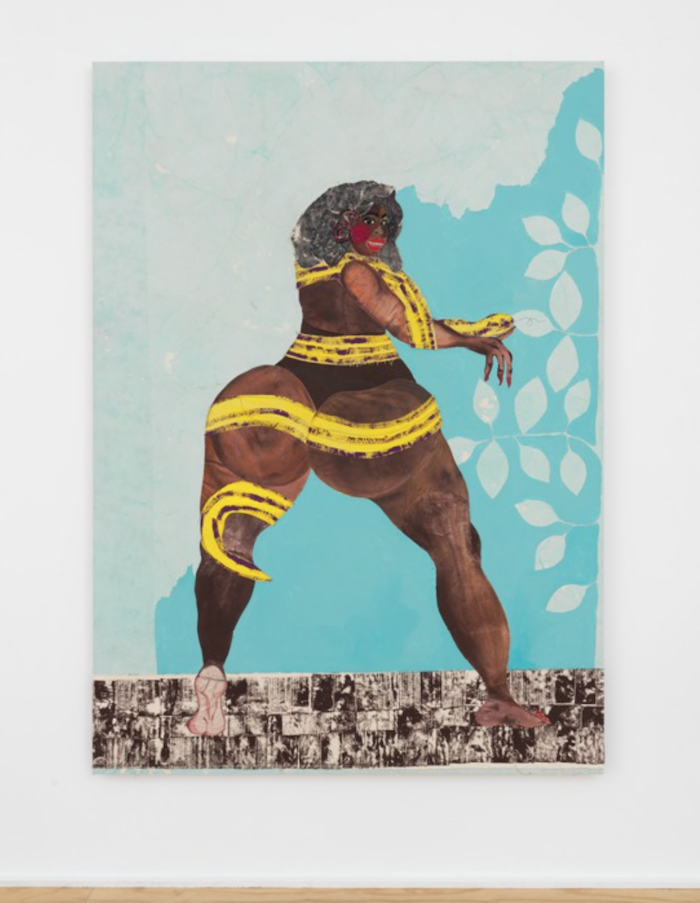

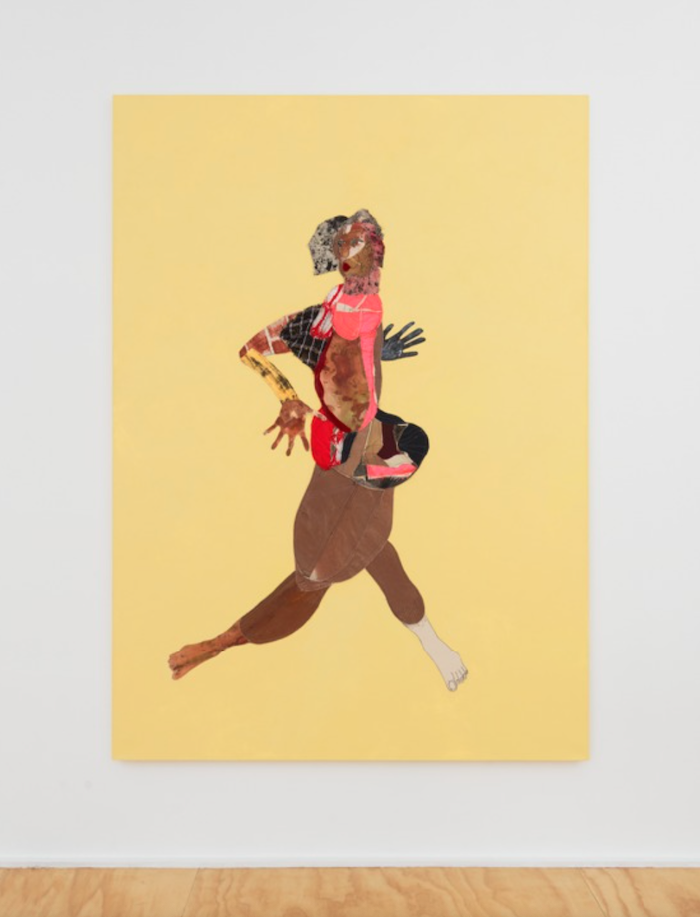

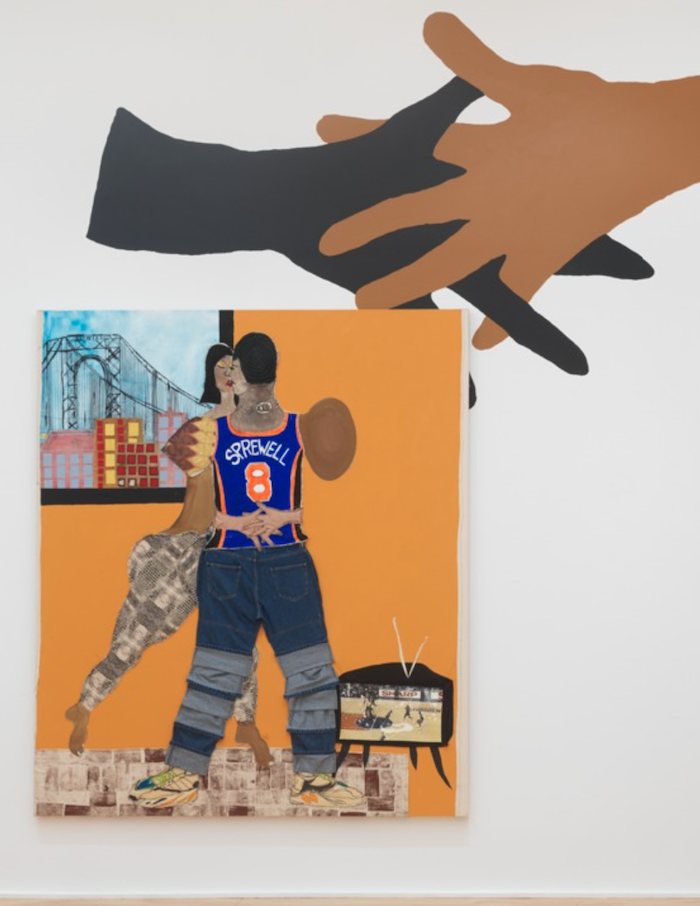

Each of the paintings in Cotton Mouth was painstakingly constructed by the artist. Formally, they could be read as multimedia collages, considering the marriage of paint and thread, though they lack that central ingredient in collage work—adhesive. The method of construction consistent throughout Self’s practice—stitching—carries an autobiographical and emotional significance. Self’s primary muse aside from herself—her mother—memorably used her hands to clothe and create for Self and her family. The labor in each stitch holds memory, affection, and protection.

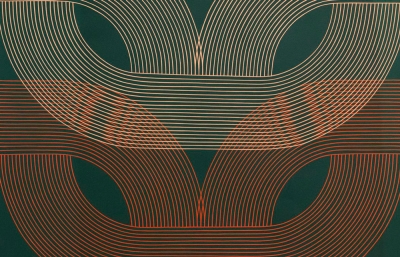

Personal sentiment unfolds into something larger with the consideration of material and formal content in the work. “Cotton Mouth” indicates a cultural and historical significance specifically referential to elements within the Black American lexicon. “Cotton has a supercharged history for Black Americans specifically,” says Self. “[It speaks to] Black Americans’ labor and sacrifice—and tangentially embodies the Black American experience of American chattel slavery.” As a material, cotton has a ubiquitous presence in everyday life, proving essential to almost every person on earth, but is infrequently acknowledged as the fruit of exclusively Black slave labor, accounting for over half of all American exports during the first half of the 19th century.

The body of work Self presents in Cotton Mouth is intended to speak to the unique phenomenon of Black American life through references to contemporary culture and Black America’s past. Self purports, blackness, like all identities, is based on a personal mythology—mythology being that which is half fact and half fiction. In the contemporary sphere, Black pop culture can be understood as the primary embodiment of “modern-day folklore” to use the artist’s own words. Within the title of the show, we also find reference to this practice of imparting knowledge, central to the African diasporic tradition. “I was thinking of the importance of oral history and diaspora as a way to carry lessons, information, or historical events to the next generation,” explains Self.

Most of the work in the show is situated in simulated spaces mimicking the home. “Domestic space is one of indoctrination and is the primary environment in which one receives information,” says Self. In the diptych Spat, a couple is engaged in a tenuous conversation, with the female figure on the left cross-legged and facing her partner. The male is on the “lashing end” of the argument, his vulnerable state made apparent by his visible rib cage. In Sprewell, Self pays tribute to the immediacy of honest emotion and intimate romance. The work references NBA star Latrell Sprewell in a #blacklove vignette—a Sprewell jersey worn by the male protagonist in the piece hearkens to the controversial choking of his coach in a pointed demand for agency and poignant expression of fury and resilience.

This bodily rage is respected, retaining its humanity and complexity throughout Self’s entire body of work. Beasts play a constant and important role in Western mythology and “oftentimes that symbolism is conflated with blackness,” suggests Self. The parallel agendas of dehumanization and racism are examined and rebuked through the nuanced animalistic references that appear in the show.

Self’s narratives are non-linear, proposing a variety of conclusions and introductions. Her paintings thrust words into spaces where speech has been denied. “People say they have cotton mouth when they smoke too much and their mouth ceases to function,” says Self. The choice of title is a burdened one, as a mouth that can no longer function serves as a metaphor for the systemic and continued silencing of Black America. Cotton Mouth is a continuation of the lore, which has kept Black people alive, in communion with their history, and alert to the possibilities of their future.

“The work exists within a vacuum of blackness,” states Self, who favors Black subjects, pulls inspiration from within her personal experience and the Black community she navigates daily (whether in New Haven or Harlem), and intends the work to be consumed and engaged with by Black people. Self’s figures have been referred to before as “exaggerated,” a term that reveals the white-centric perspective that previous critics have exhibited. In reality, her subjects are not fictive, nor do they have enlarged or highlighted features but, rather, are rooted in reality and frequently take cues from the body of the artist herself. Self’s psychic energy is poured into the work, through her hand stitching (usually undertaken with the in-process work laid flat on the floor) and through the materials. For Sprewell, Self repurposed favorite jeans she could no longer fit, utilizing her body and its changes to create work packed with meaning both literally and figuratively. The other pieces within this show exhibit that same bodily integration in a sensitive and robust way.