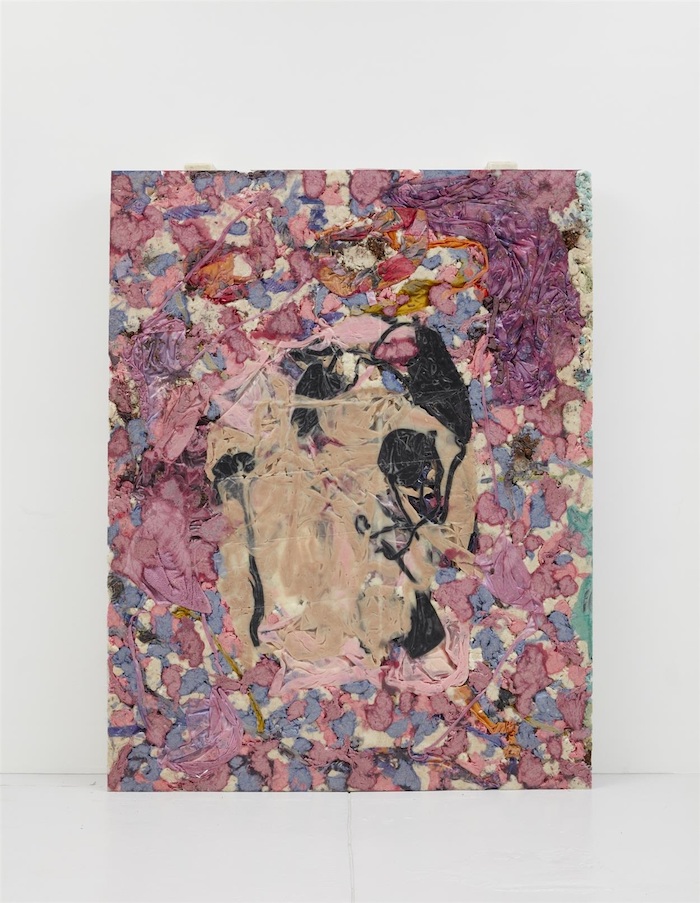

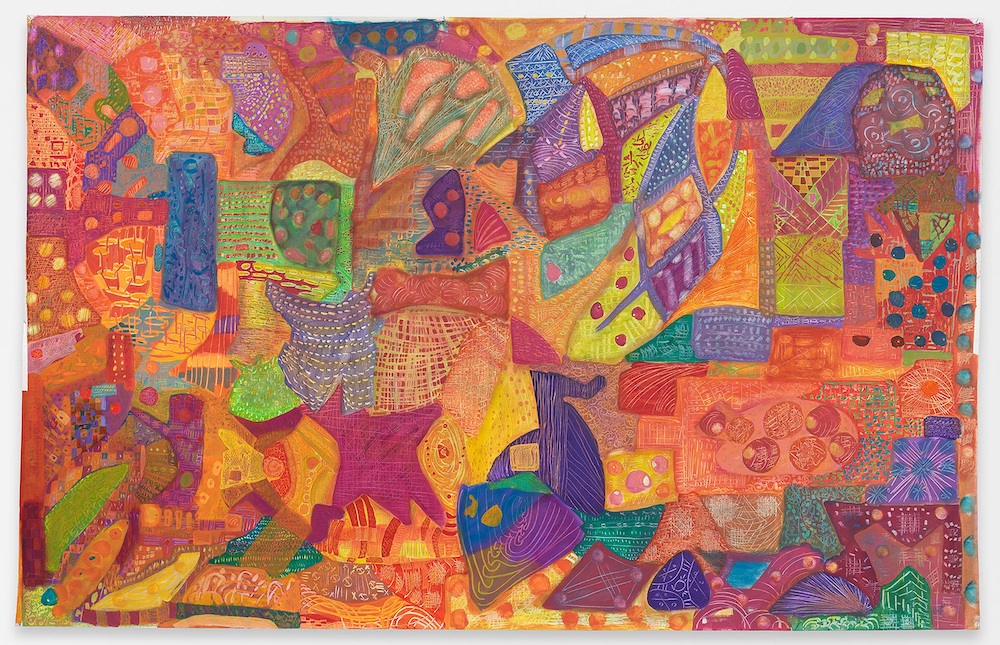

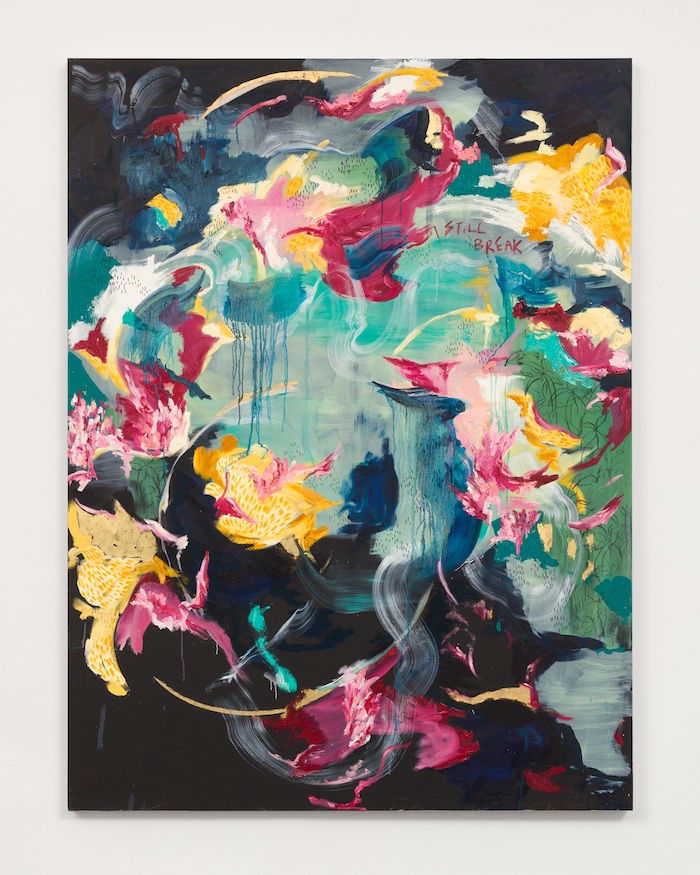

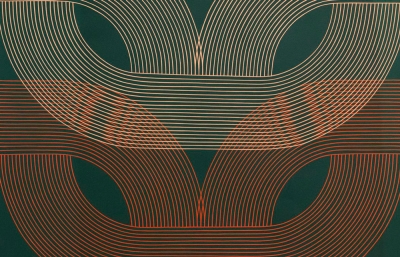

The Green Family Art Foundation is pleased to present Black Abstractionists: From Then ‘til Now, curated by Dexter Wimberly, opening on October 8, 2022 and remaining on view until January 29, 2023. This show focuses on Black abstract artists spanning multiple generations, starting in the 1960s with Alma Thomas and ending with young artists working today, such as Michaela Yearwood-Dan and Vaughn Spann. The history of Black artists working in abstraction is inseparable from the history of modern and contemporary art.

Black Abstractionists: From then ‘til Now

By Dexter Wimberly

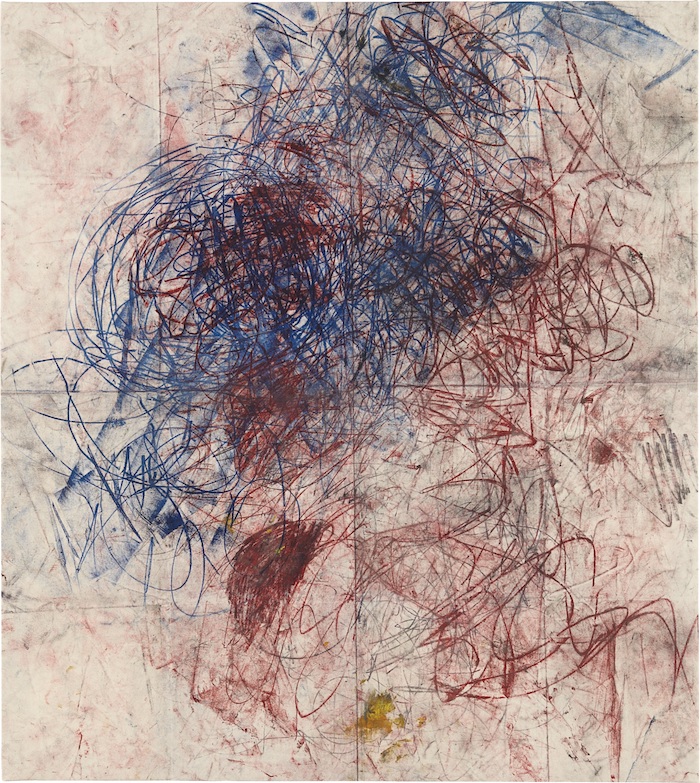

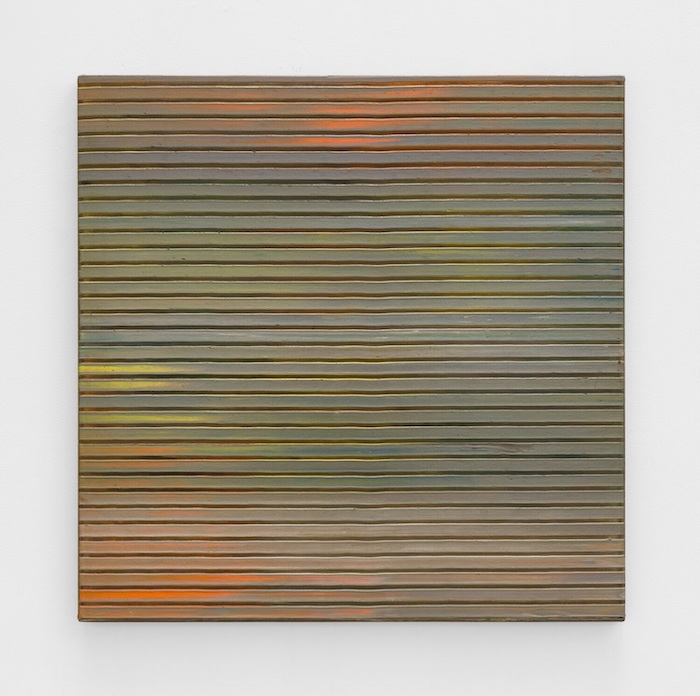

Black Abstractionists: From then ‘til Now brings together a multigenerational group of 38 pioneering, mid-career, and emerging Black artists. The history of Black artists working in abstraction is inseparable from the history of modern and contemporary art. While they were often marginalized by the art world power structure of museums, galleries, and collectors for most of the 20th-century, the contributions of Black artists were inexorable. During one of the most radical periods in 20th-century American politics, the Black Power era, a group of Black artists was working with what was, and still is, one of the most radical forms of art abstraction. Radicalism is relative, though, and in this case politics and culture were on different tracks.

In America throughout the 1960s — as the civil rights movement crested, calls for Black Power sounded, and the Black Panther Party was birthed — the aesthetics of Black artists became itself a kind of revolutionary proposition. In 1965, after the assassination of Malcolm X, but several months before the passage of the Voting Rights Act (landmark legislation that prohibited racial discrimination in the American electoral process), the poet LeRoi Jones (who would later change his name to Amiri Baraka) founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater School in Harlem — effectively inaugurating the Black Arts Movement. The writer Larry Neal, his collaborator, described the movement’s goal to create art that “speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America,” one objective of which was nothing less than “a radical reordering of the Western cultural aesthetic.” Figurative painting and sculpture were key components in how this reordering took place, and some of the most enduring visuals from the movement were explicitly realist depictions of Black people, their heroes, history, and their activism.

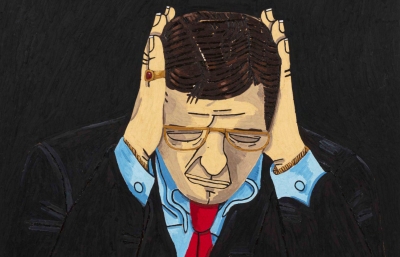

It took courage, focus, self-awareness, and ambition to be a Black artist making abstract paintings at that time. It would seem at that moment that certain Black artists were being backed into a corner: on the one side, they were excluded by mainstream institutions and the prevailing critical establishment, while on the other they were browbeaten by Black art watchdogs demanding adherence to a Black art orthodoxy. The relationship between Black abstraction and Black activism was tenuous and philosophically fraught. White art audiences, including those limited number of galleries, who were willing to inventory, sell, and buy art made by Black artists, expected that art to embody the experiences and trauma of racism, which often meant didactic figuration. A certain tradition of Black activism also considered abstract art too ingratiating to mainstream Euro- American tastes, too mute on the pressing realities of racism.

The issue concerning “authenticity” and “the Black experience” is generally discussed in relation to the Black Arts Movement and its preference for images that contested the pervasive vilification, ridicule, and disparagement of African Americans in US popular culture. But the split that imagined “African American artist” as incompatible with “abstract artist” predates the Black Arts Movement by decades. As abstraction gained momentum after World War II, Black American artists were at the forefront of aesthetic debates, but unlike their white counterparts, they also had to contend with an art world that saw them first as Black and second as artists. In his 1946 essay “The Negro Artist’s Dilemma,” Romare Bearden criticized the tendency to evaluate work by Black artists based on “sociological rather than aesthetic” criteria. Although Bearden himself worked in a more representational vein, he was acutely aware that as long as the sociological dominated the conversation, the formal innovations of both figural and abstract artists of color would continue to be dismissed.

In all instances, Black representation has involved the confluence of an artist’s individual perspective or desire for personal agency with the discourse of these movements circumscribing the parameters of Blackness in art. There has been a tendency toward figuration and realism in these movements, which have operated on principles of transparency, immediacy, authority, and authenticity. These well-meaning efforts ultimately reinforced a reductive notion of “Black art,” or the idea of an essence locatable in works of art by Black artists.

The exhibition is located at 2111 Flora Street, Suite 110 Dallas, TX 75201. Admission is free.