The following was published in the August 2015 issue of Juxtapoz, our loosely themed "Environmntal Issue."

Nature is an unruly place, forever getting in humanity’s way, regularly tamed but regressing back to the feral. As an aesthetic paradigm we admire its majesty, take pleasure in its picturesque and swoon at its beauty, but as a psychological fact, let’s face it; unless you’re Paul Bunyan, Daniel Boone or Johnny Appleseed it can quite rightly scare the shit out of you. And into this wilderness of overgrowth and undergrowth, impossibly daunting scale, tempestuous elements, natural predators and truly rugged discomforts, Americans have forged not simply a viable negotiation of space and a culture of refuge but a national identity that is in seemingly equal parts as much an ongoing myth of our frontier heritage and an aspirational self-perception of our Eurocentric course of civilization. How, one wonders, in this miasma of collective delusions and the arrogance of our manifest destiny, were we ever able to see the forest from the trees?

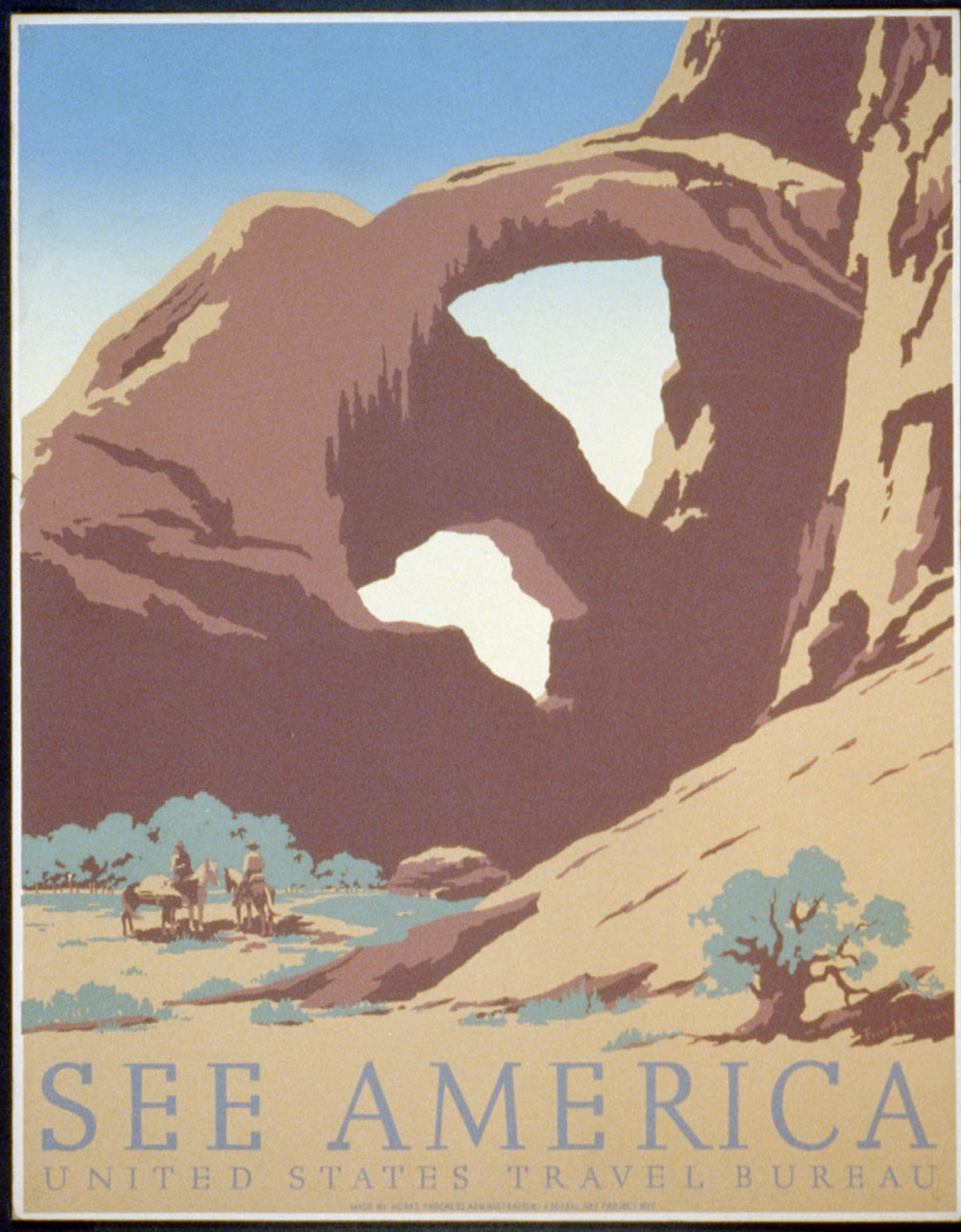

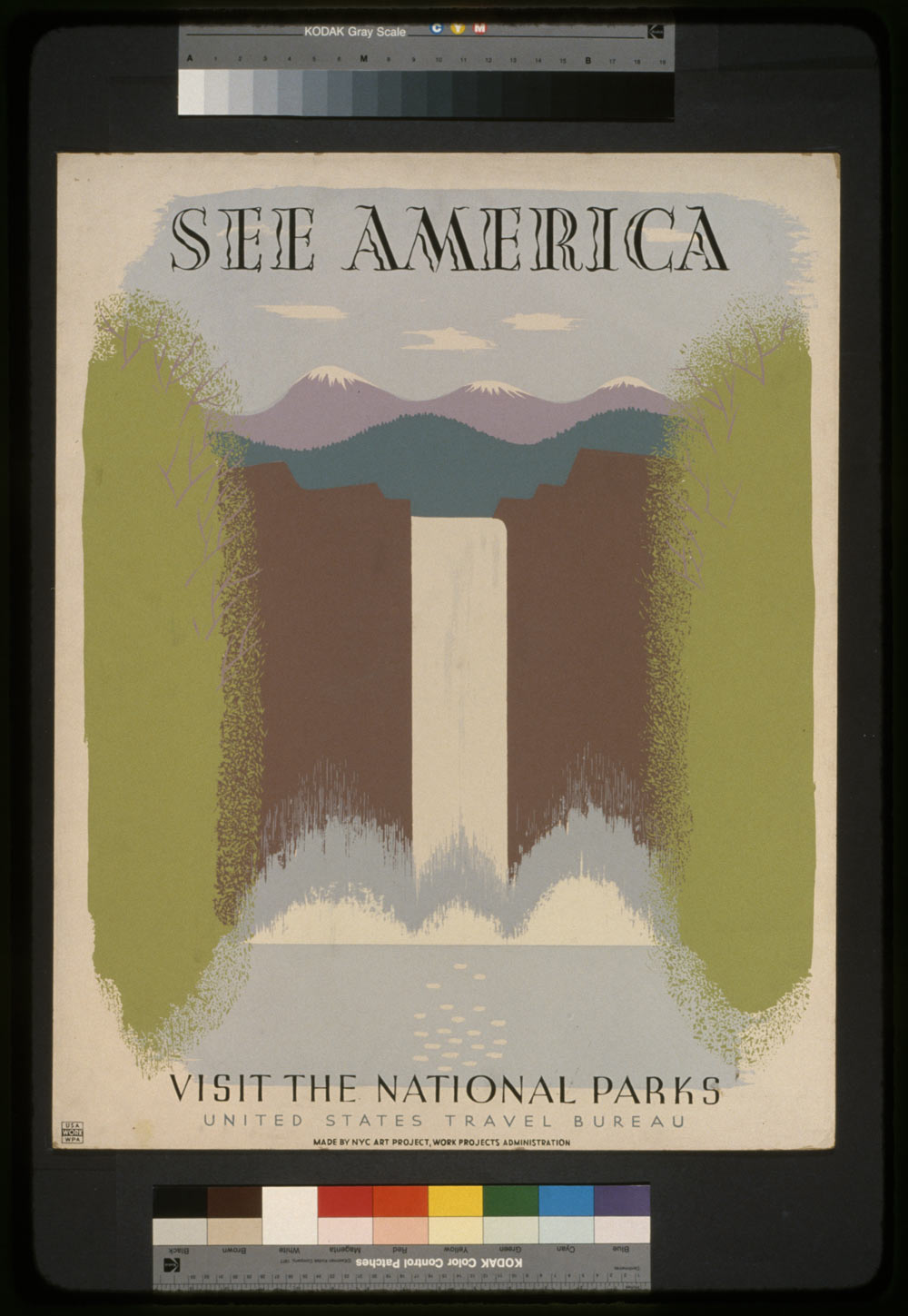

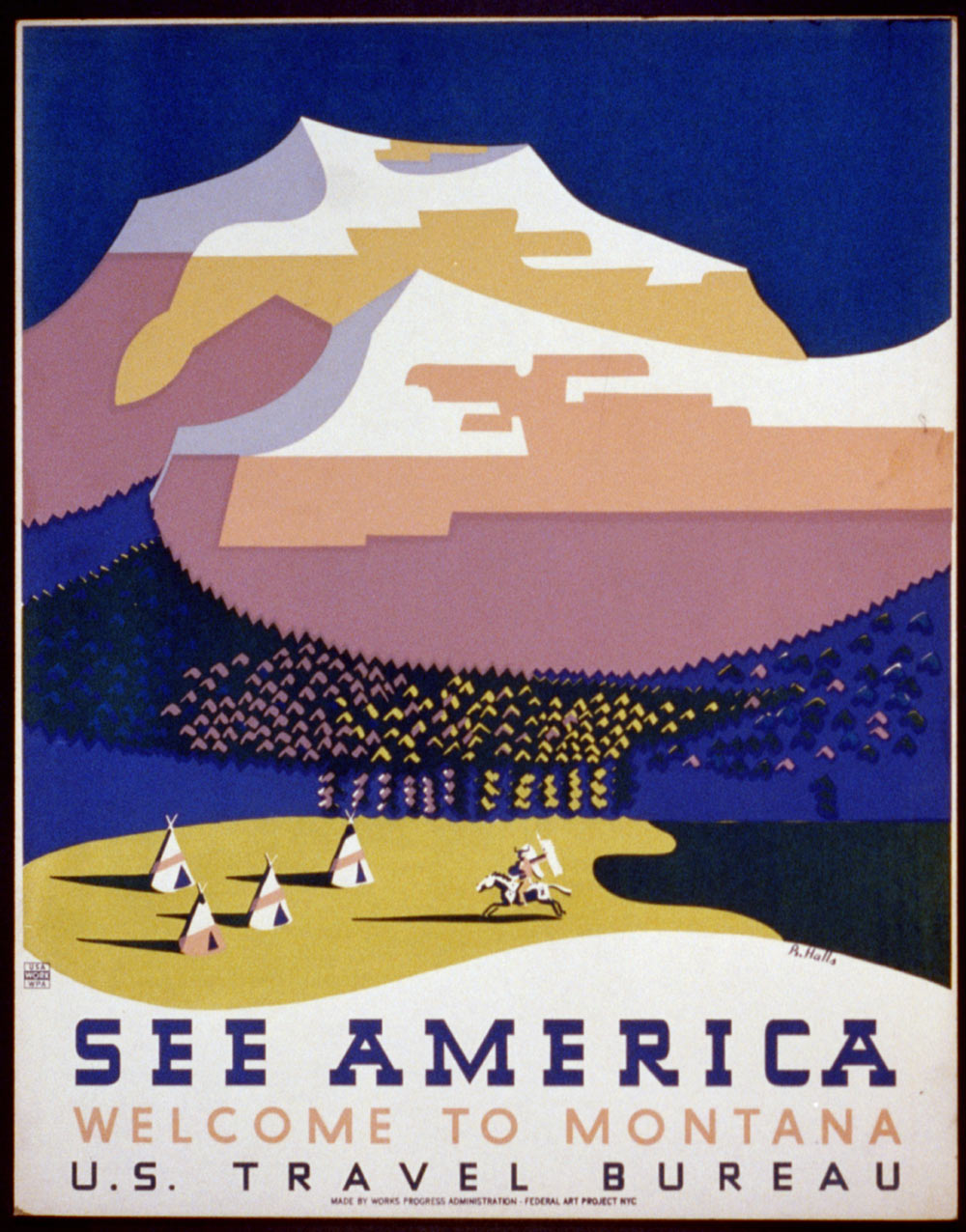

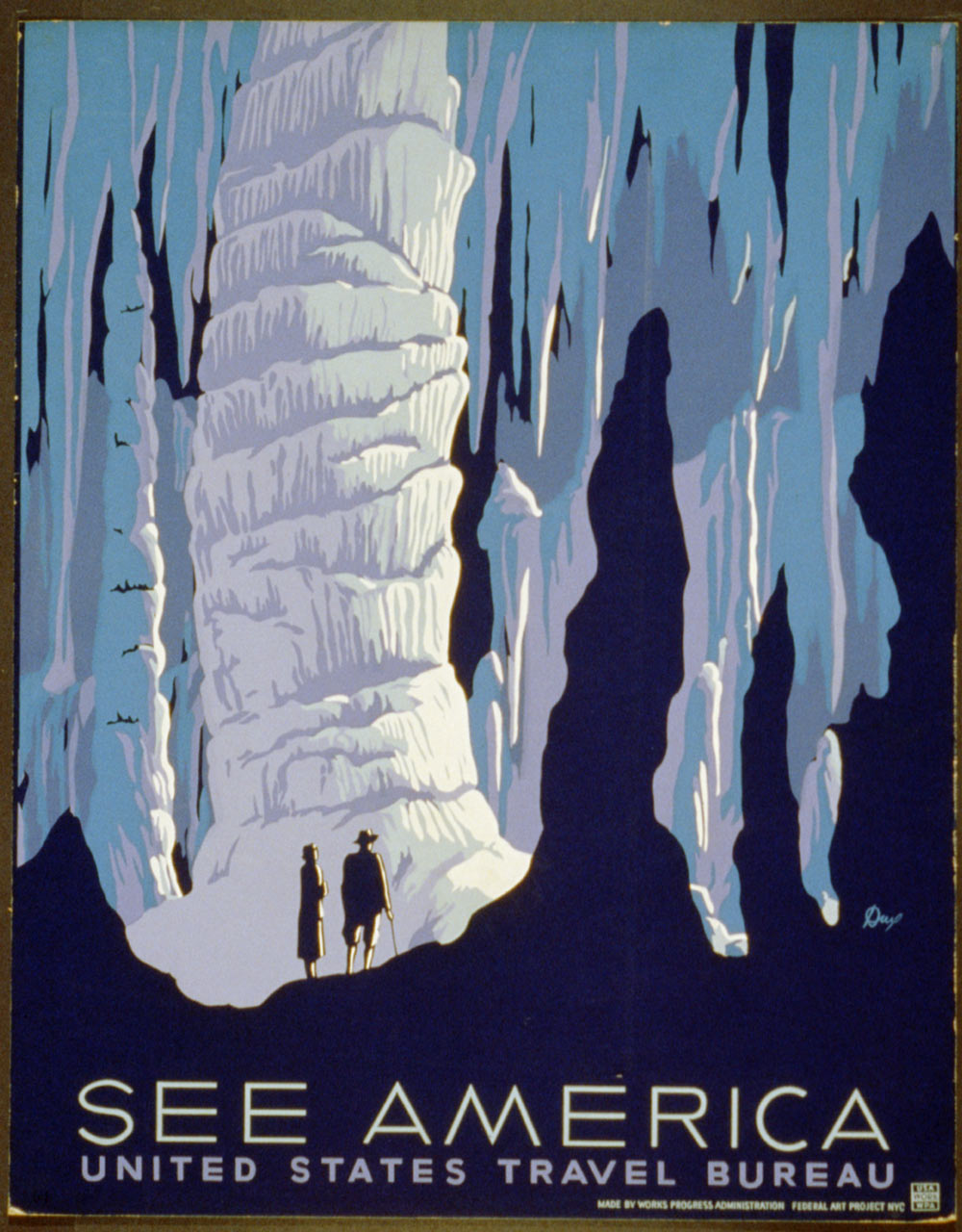

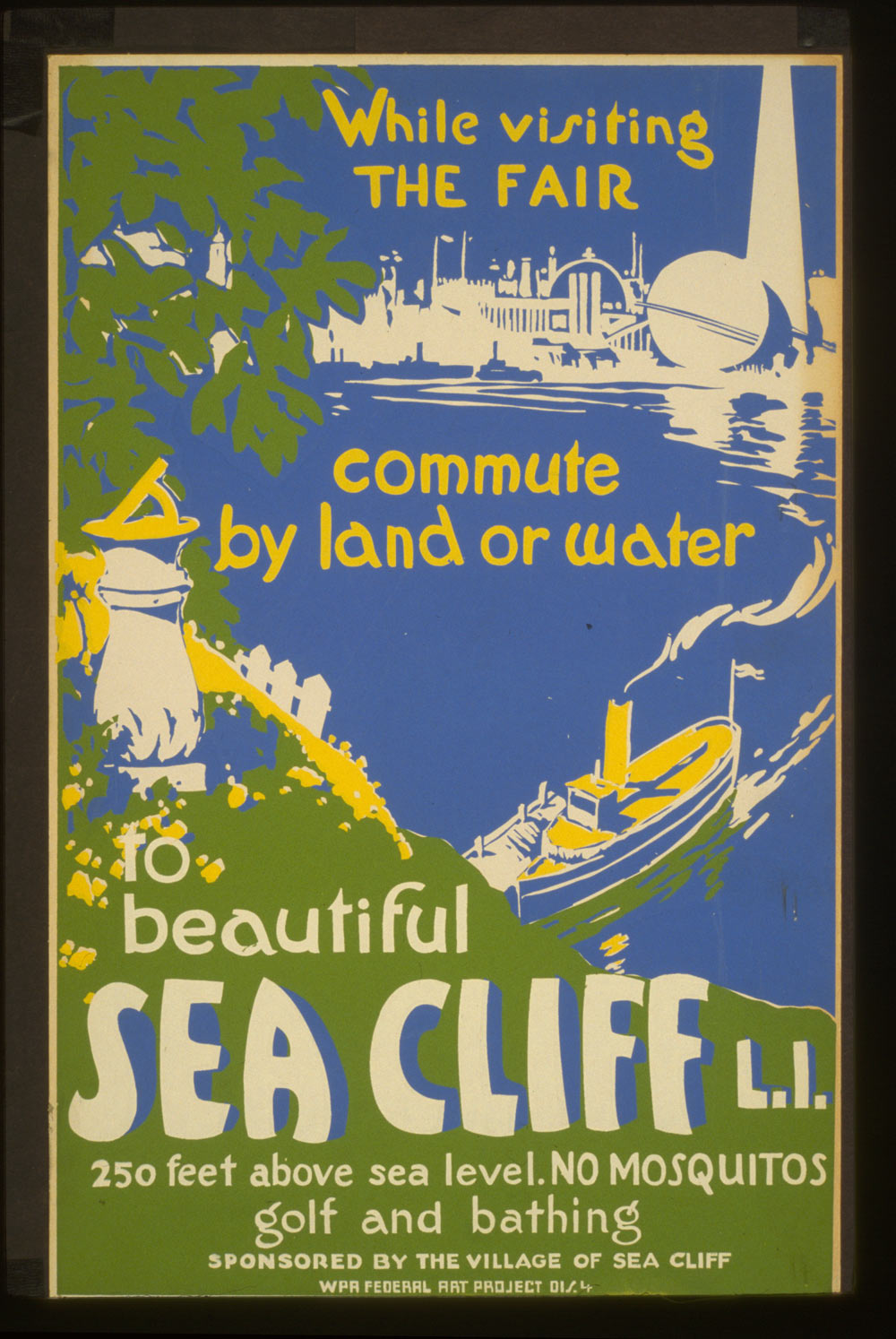

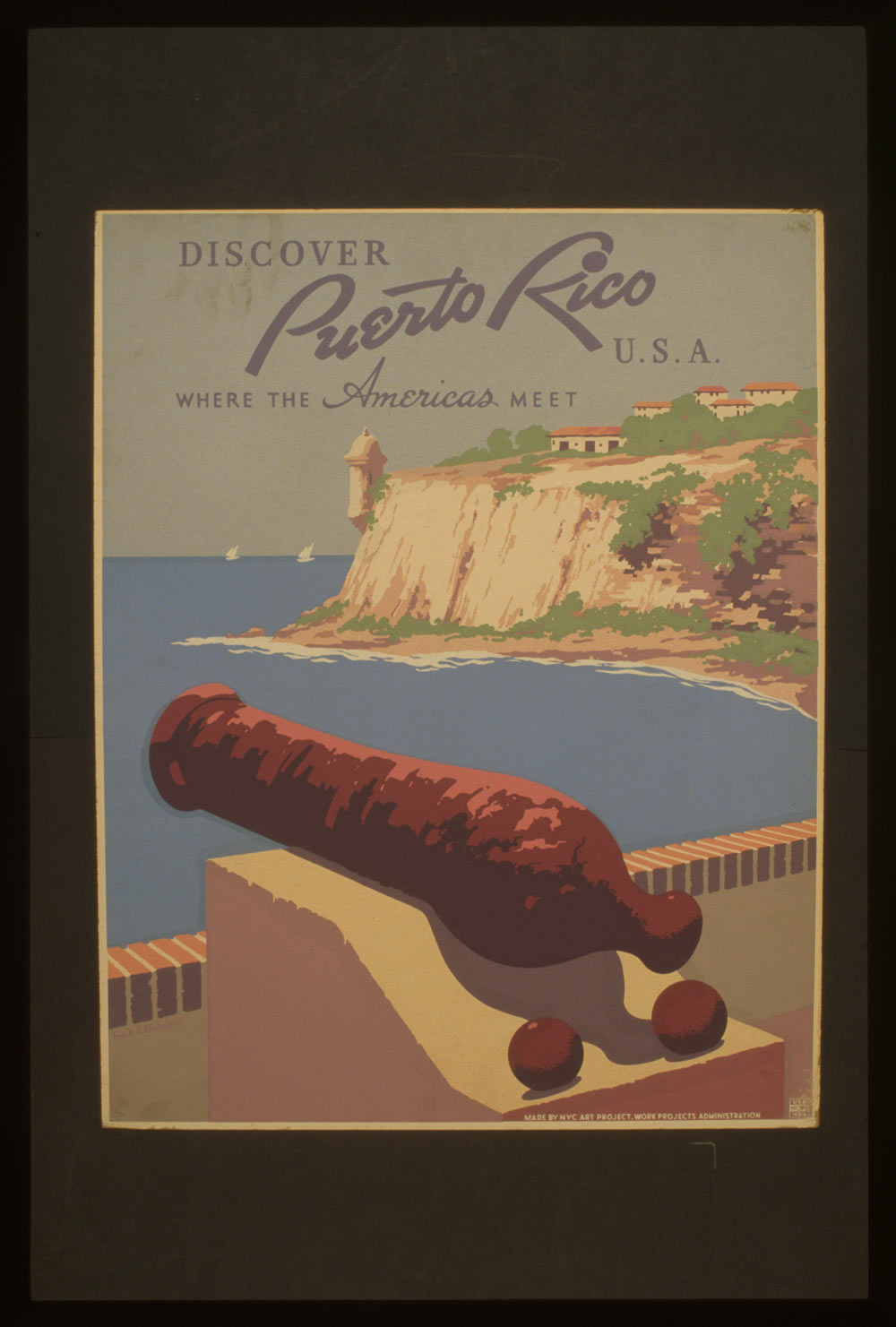

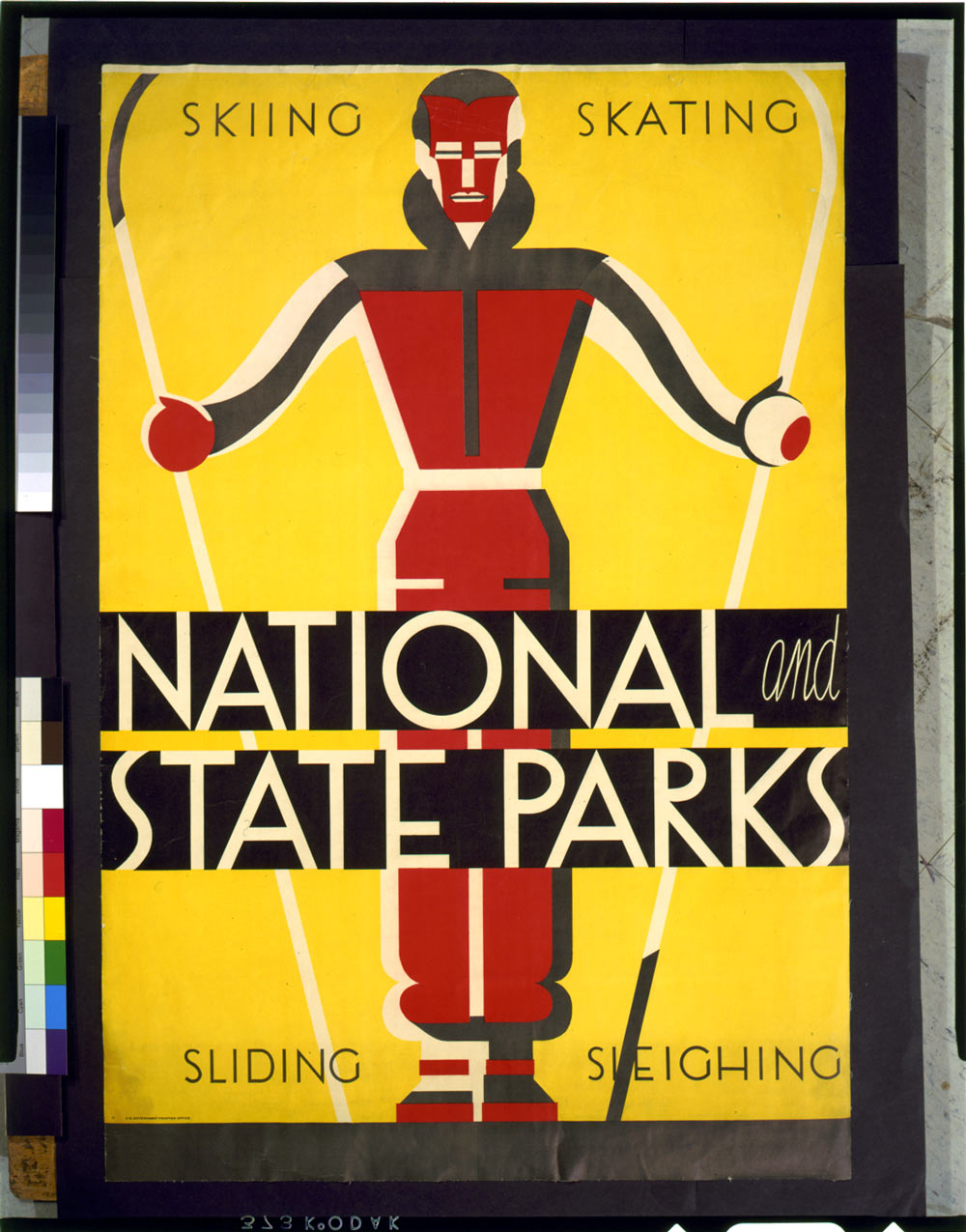

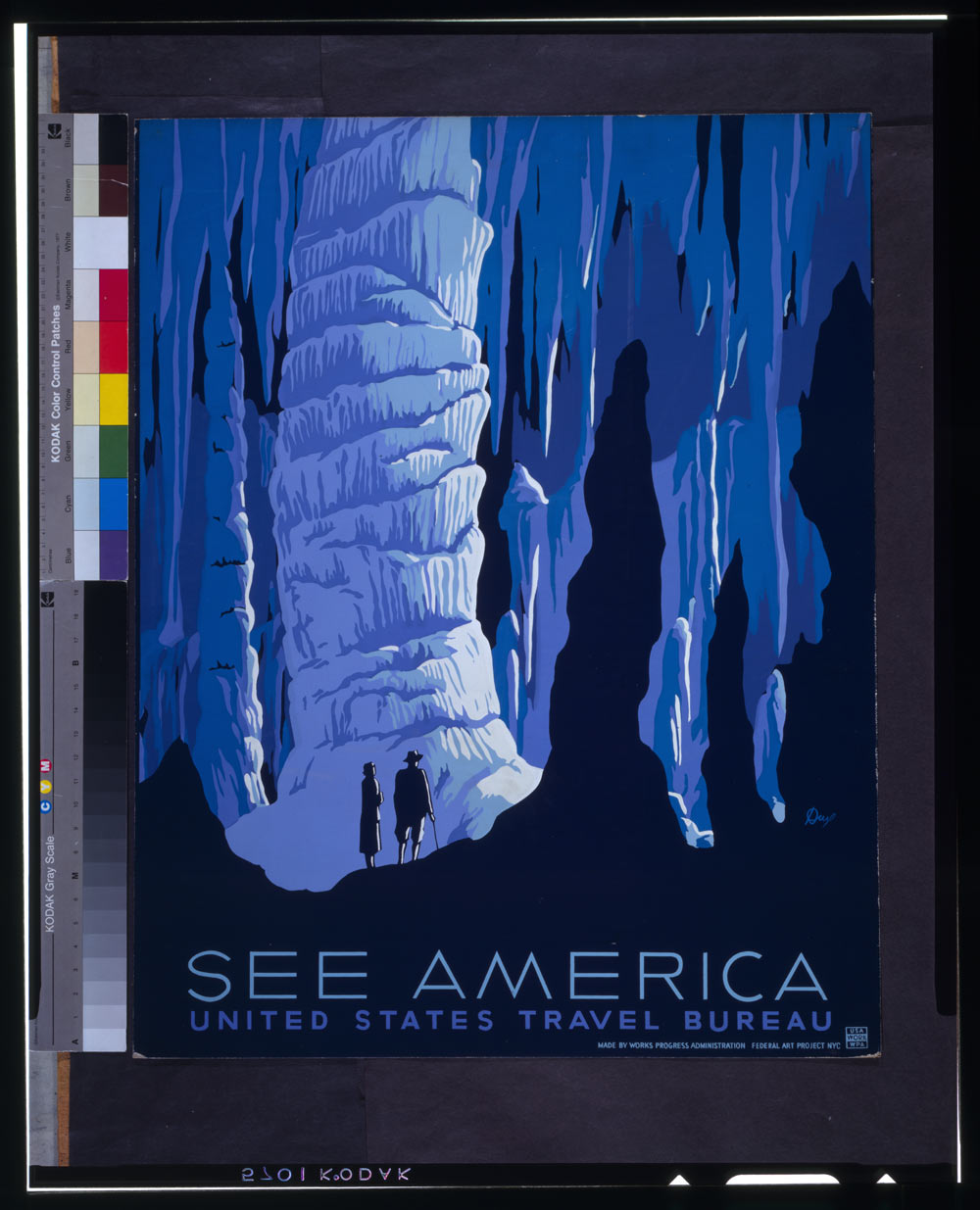

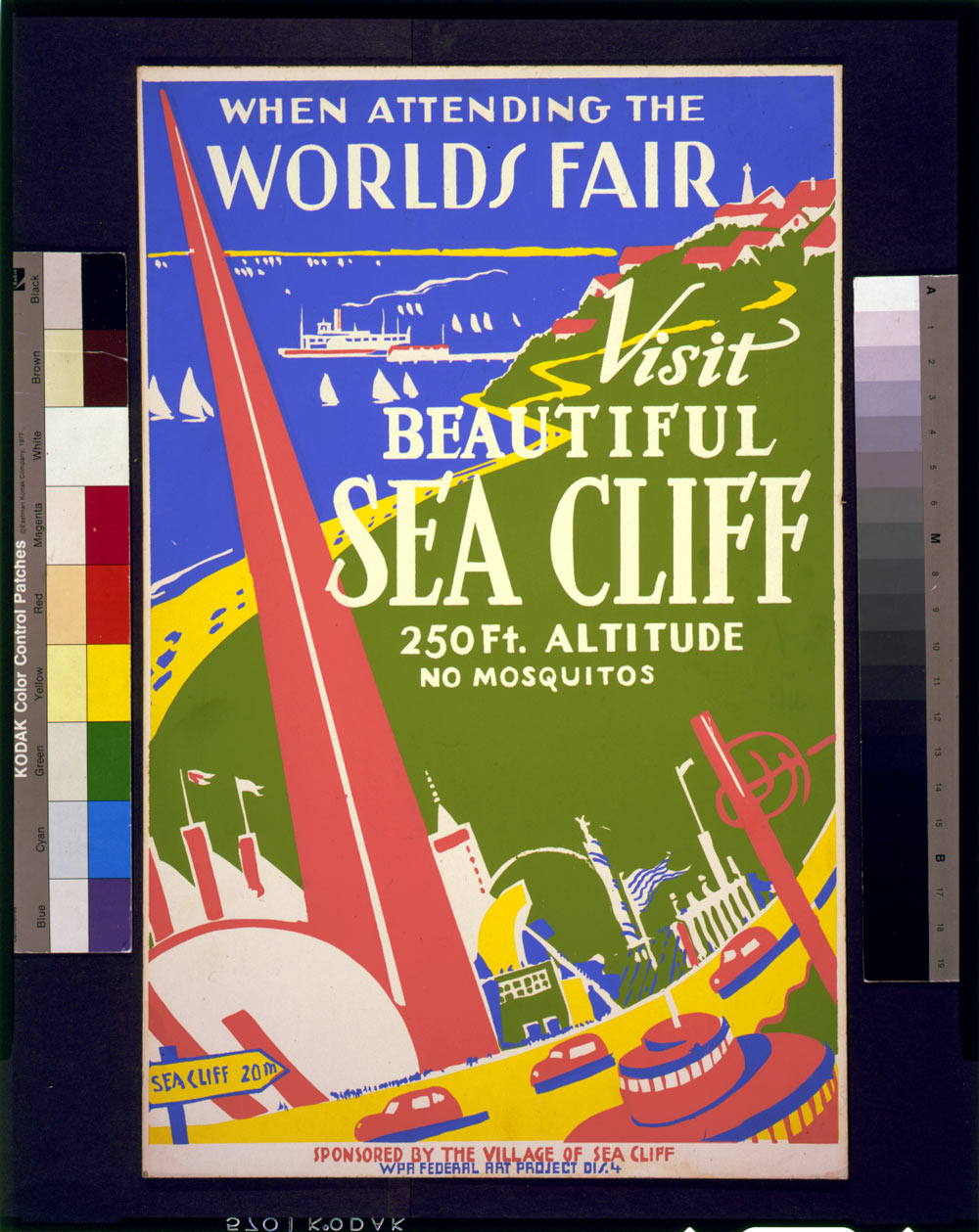

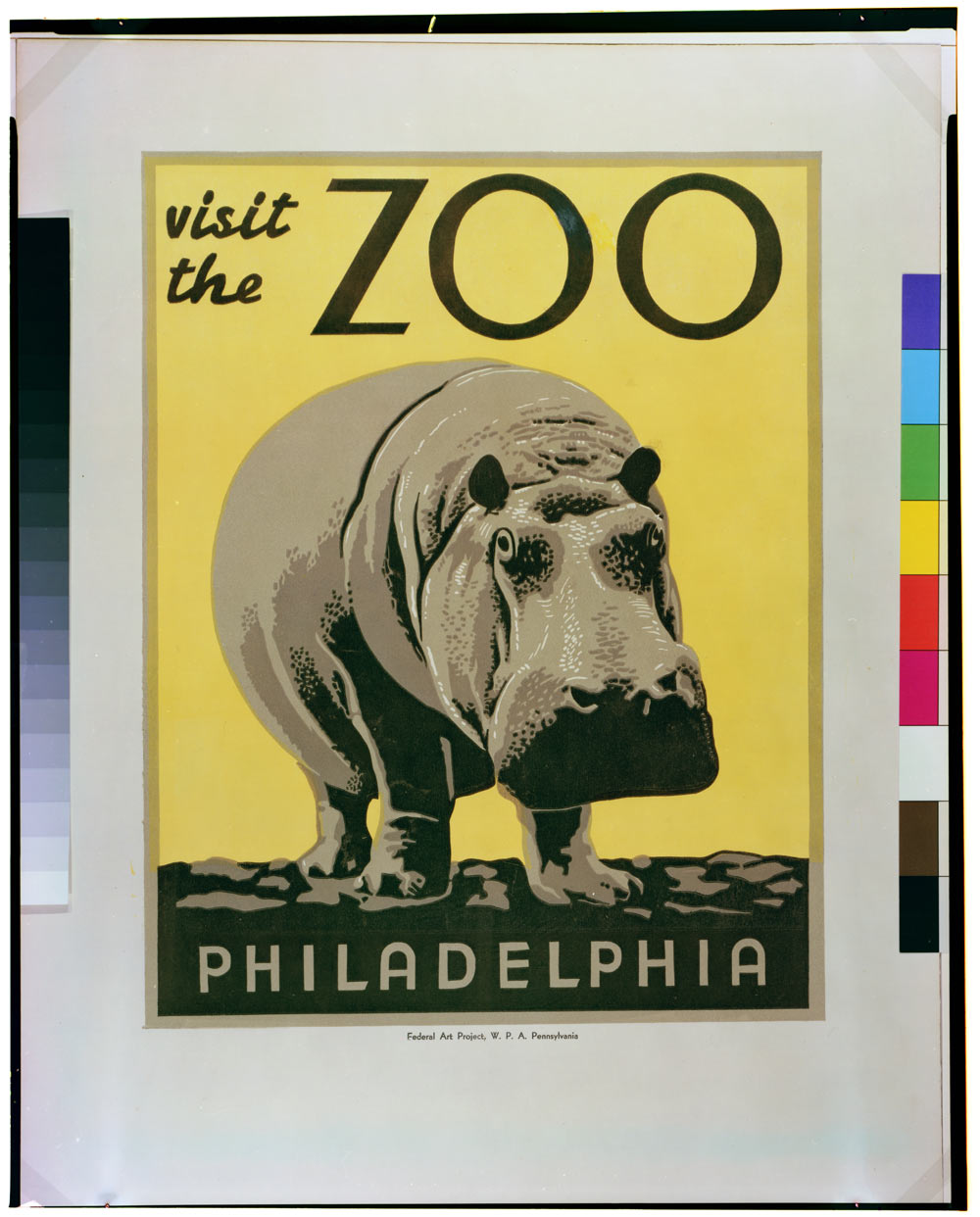

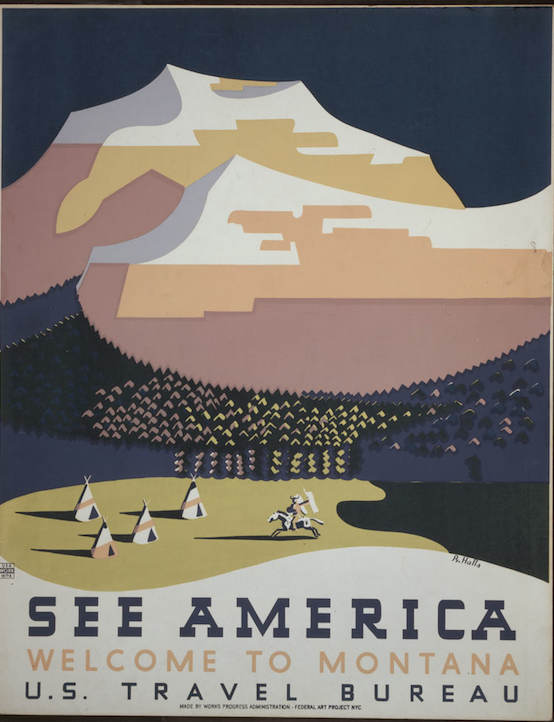

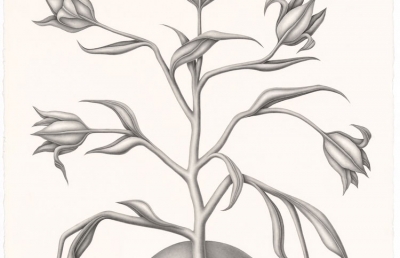

The consummate dream factory that is the United States has had the uncanny ability to transform our vision of self as the face of the land we live on, while in fact transforming the land to physically manifest what we are. From the folkloric to the Transcendentalists, the naturalists to the plein air painters, we’ve long been imagining nature, but perhaps never so vividly as we did in our single most crisis of confidence, the Great Depression. “See America,” a campaign to promote our many natural wonders, constitutes just a fraction of the many posters produced in the late ’30s and early ’40s by the Federal Arts Project, which employed artists as part of the Works Progress Administration. Under this rubric, the WPA provided employment to thousands of artists and relief from the Depression, spawning hundreds of thousands of art works, most notably through the Public Works of Art Project in which schools, libraries, hospitals, post offices and all manner of public and municipal buildings became canvas for perhaps the greatest explosion of mural art since the Renaissance. Willem de Kooning spoke later of the experience; “I changed my attitude towards being an artist. Instead of doing odd jobs and painting on the side, I painted and did odd jobs on the side. My life was the same, but I had a different view of it.” De Kooning is only one of many of America’s most celebrated artists who enjoyed such support.

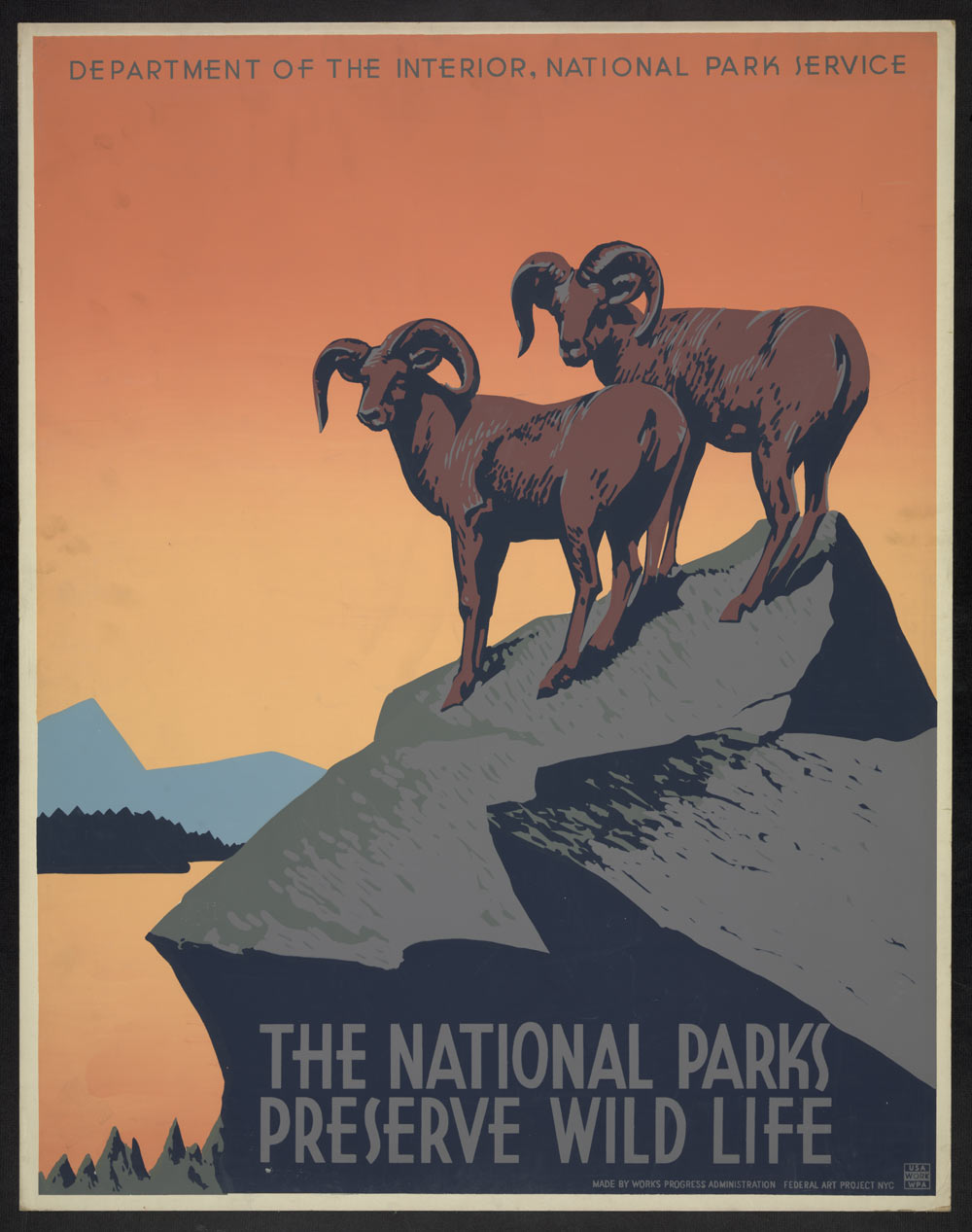

What the Federal Arts Project provided, far beyond some vitally needed sustenance for our artists, was a vision for America in its own time of need, a national identity that took its strength from one thing we believe in more than any god: the land. Just as the See America campaign worked to motivate people to enjoy the free entertainments of our national parks, the Farm Security Administration created a rural photography program that, in its time, employed such greats as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Gordon Parks. Their portraits of life on the farm and the deprivations of the rural south are still what most of us today call to mind when we picture the Great Depression. Though it is a big leap from the majesty of See America’s nature to the poverty of the FSA’s photographic record, both, in fact, speak to that very American sentiment that when the politicians and financial institutions fail, it is nature itself that can make us whole again. And both understood, far better than the muralists or the other programs supporting theater, film and other mediums, that the power of their message relied on its simplicity, that to render the scale of what this country was about, you had to be iconic.

Nature, Represented

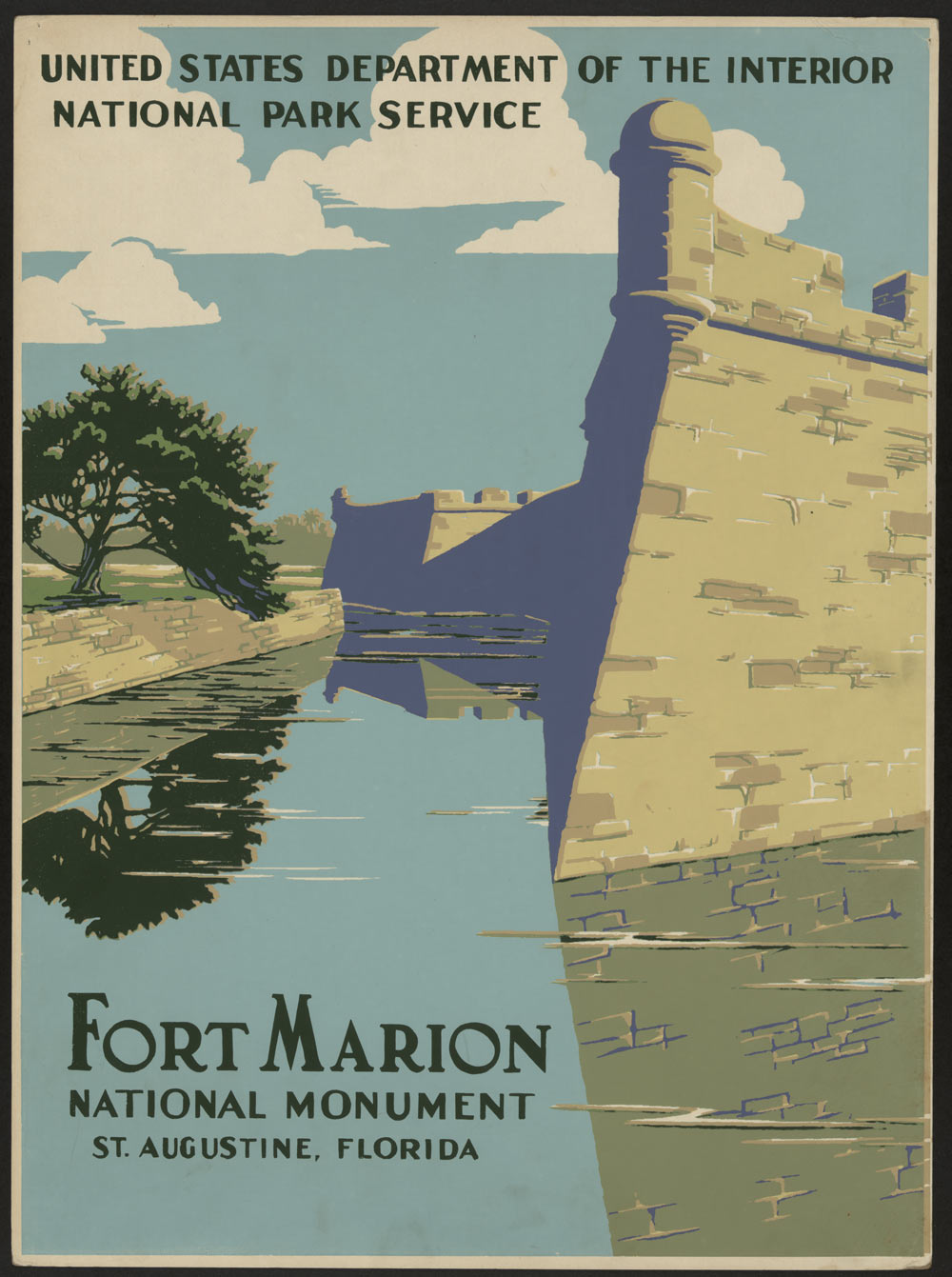

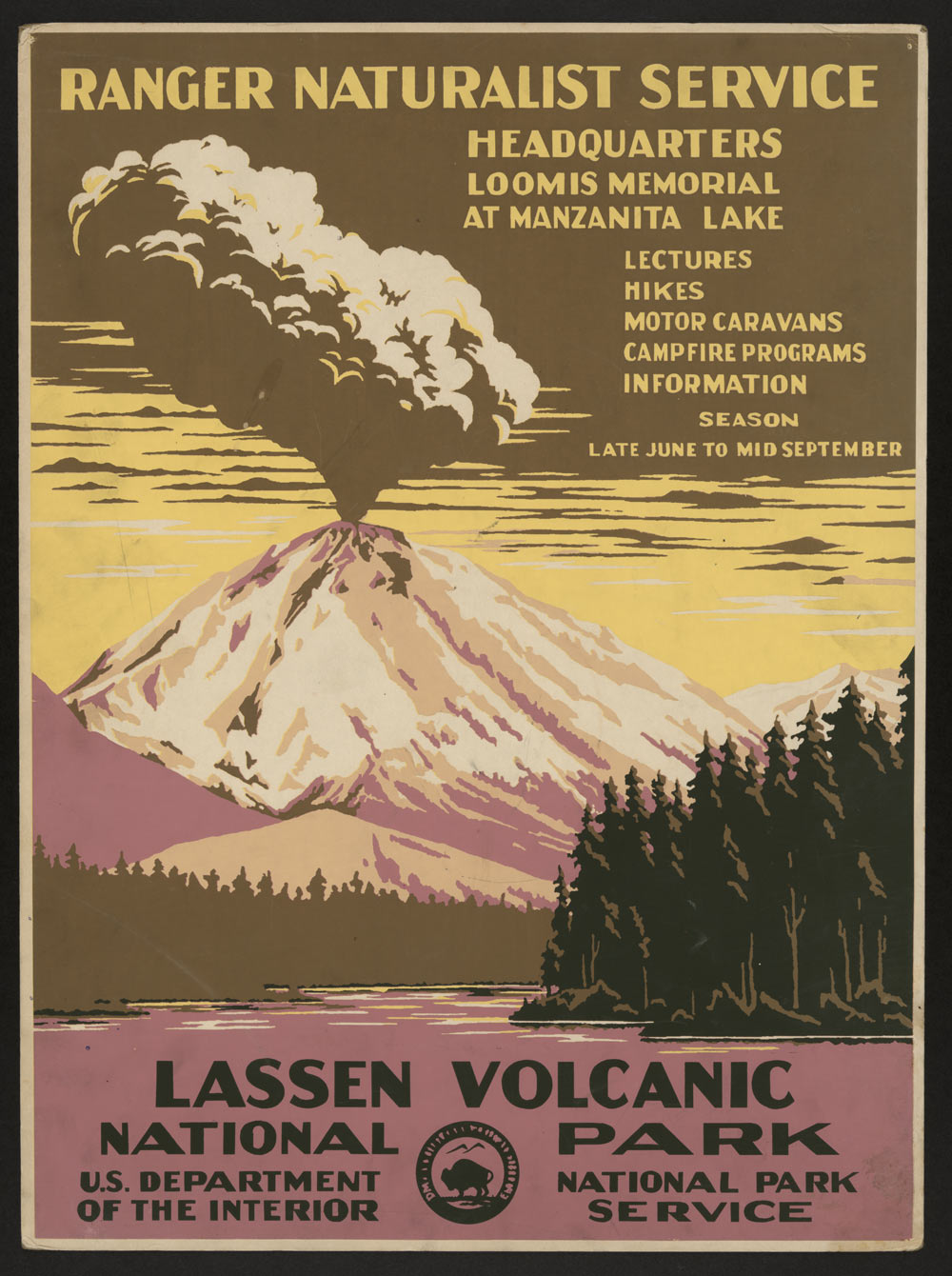

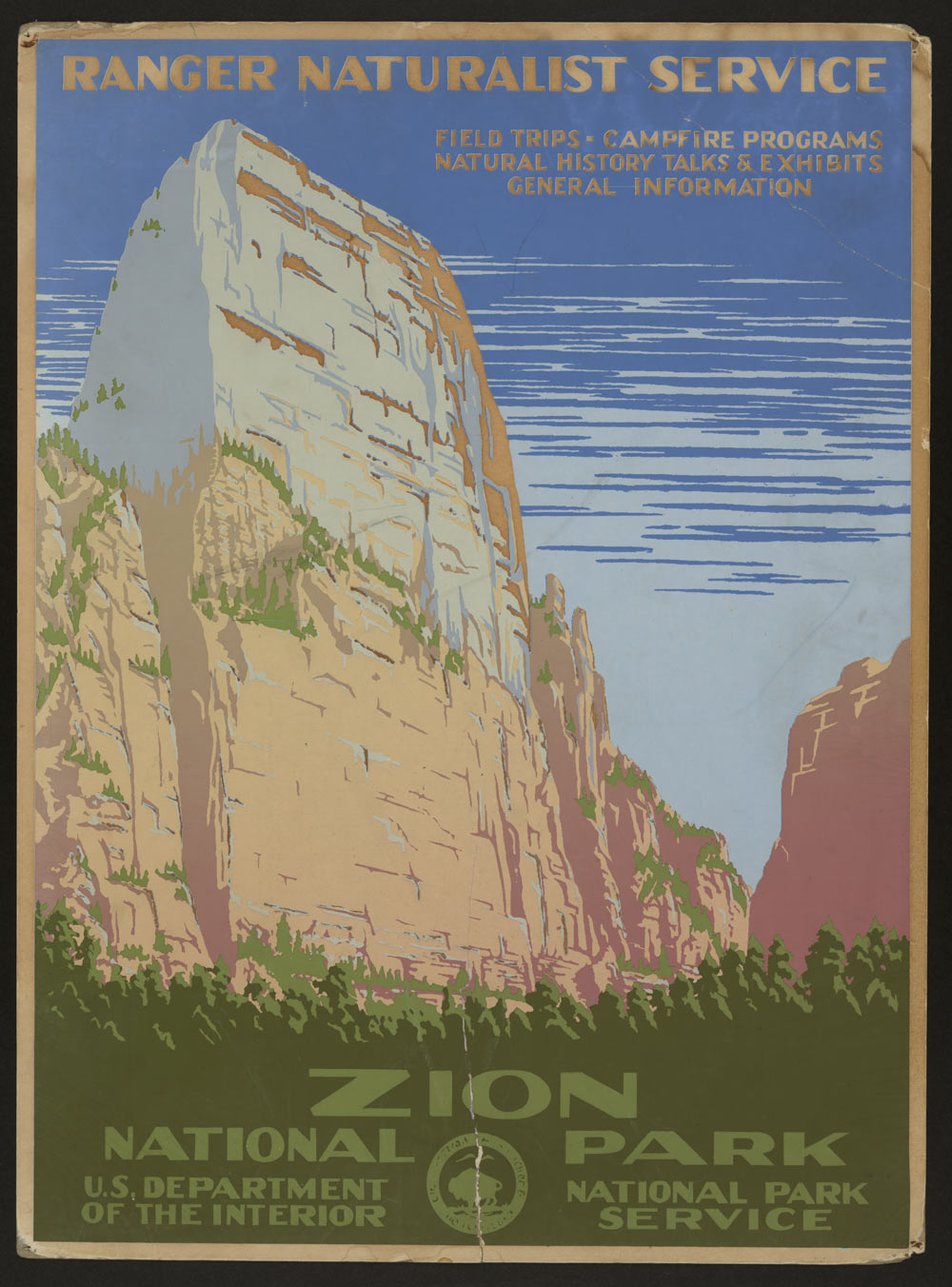

All the thousands of posters created over this period were for one government agency of another. See America was employed in the name of the Department of Interior, assisting the National Parks Service and the US Travel Bureau. There is something familial in that it was Teddy Roosevelt, the conservationist president, who established our national park and forest services, while it was his cousin FDR’s posters that helped us appreciate them. Advertising what already belonged to the people as if it were a consumer product, See America extolled our myriad national treasures, from the Carlsbad Caverns, Yellowstone and Bryce Canyon to Niagara Falls, the Everglades and the Grand Canyon, conveying their glory, as much a matter of pride as an exhortation to tourism. With the same pedagogical intensity of most any other government-issued educational didactics (other FSA posters of that time seem unduly concerned with issues of our health and safety), these works combine the charm of illustration in the era before it was wholly supplanted by photography with the visual acuity of propaganda. As representations of nature, these are smartly reductive, conveying a clarity that eschews the typical sentimentalities of landscape art without forsaking beauty. Here, grandeur is made iconic, the imposing dimensions and intimidating complexity of nature distilled into something more like a logo, an emblem of the immense and a sign of the sublime.

America, we must understand, is a chimera, ultimately directed by how we envision it, be it a bountiful land of plenty or a frail and battered nature that needs ecological protection. Oddly, we have a habit of seeing it best just when it starts to disappear from sight. In all the time that wilderness threatened and acted as an obstacle in the path of our progress, we hardly thought much more about it than as the terms of our survival; but when we belittled it down to size and transformed it into a more benign nature in consort with human endeavor, we began to contemplate and appreciate its poetic and narrative character. Over the course of the 19th Century, from Emerson’s “Nature” through Thoreau’s Walden, or from Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales to Thomas Cole, Frederic Church and the Hudson River School, we can chart the gradual diminishment of wilderness conversely through its growing influence on our imagination. Just as Thomas Cole sought to locate the sublime, that is the fearsome, in nature after much of its power over us had been tamed, so too, do we see most of our fictions like the pioneer stories, the Wild West or cowboy and Indian adventures arriving to popular culture long after the fact.

The See Legacy

With the perpetual recovery and reminiscence of a “Paradise Lost” hard-wired into the American psyche, it makes sense that it would be in our time of greatest loss and deprivation that we would return to nature as sustenance for our dreams. To fathom the mindset of a nation when the government would hire artists to depict nature for the people, we need to see America through the eyes of the Great Depression. Seemingly just tourist posters, there is a quiet politics at work within these vistas. Eventually the communist sympathies that ran rampant through the leftist-leaning WPA would seal its doom in the wake of the red scare and McCarthyism, but in that moment, nature could mean something more than the kitsch we more typically render it. It runs amok in Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, a cruelty of the dust bowl on the Okies metaphor for our social ills, it ransacks our native lands with the folly of our greatness as perpetrated by Mount Rushmore. It lays open before us as the freedom highway set forth by Woody Guthrie in his depression-era “This Land is Your Land,” where any and all can roam, ramble or follow their footsteps to find, as he describes in a verse that has subsequently been changed, “was a wall there that tried to stop me / a sign was painted said private property / but on the back side it didn’t say nothing.” That’s the side he tells us that was made for you and me, and somewhere over there is the preserve of our last bit of dignity and honor, where by chance we might truly See America. —Carlo McCormick

For more information about the Federal Art Project, visit loc.gov