The streets matter. We are in an age of great political, racial, economic and environmental upheaval. Fueled by divisive media platforms, far-right politics are on the rise around the world. So is the temperature of our atmosphere—and now, our immune systems. The promised benefits of financial capitalism (neo-liberalism) for those less privileged in society have failed to materialize, leading to the worst levels of inequality in modern history. Dual pandemics of racial and viral origins assault black and brown communities and frontline workers in grossly disproportionate levels, highlighting so much of what needs to be reckoned with and systemically changed in our shared cultures—and values.

(Hendrik Beikirch’s portrait of a local South Korean fisherman, painted on the side of the Busan Fishing Union’s building, is the largest mural in Asia. The image of the elderly fisherman rises above all other images in the city to represent the large number of South Koreans who have not benefitted from the country’s rapid economic development, signified by the glass and steel skyscrapers in the background. Credit: Public Delivery.)

Recently we have witnessed the simultaneous activation and deactivation of public spaces globally. We’ve seen how black and brown citizens of the US and across the world became more afraid of being murdered by white police officers in their communities than from the immense risks of a deadly virus. Courageously showing up and standing up in justified protest and rage against the murder of black men, women and children by racist, white supremacist police. This outpouring of rage and grief has created the largest civil rights movement in world history while a fascist US president exacerbates a manufactured civil-cultural-war and presides over the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans. We’ve glimpsed the best and worst of humanity, in real time, in all its overwhelming raw power, viscousness, beauty and complexity.

As people around the world return to public spaces and begin to move again through cities, art that can manifest creative forms of resistance to the multiple threats of fascism, racism, climate change, biodiversity loss and inequality that threaten the survival of the democratic project and our understandings of what is truly important in life is needed now more than ever. Creating art in the streets, can act as a provocation for finding – through contact with the public – new visions for the social, cultural, environmental and political possibilities of life. The act of creating art in urban spaces is a radical one that should not be underestimated and in our current moment of uncertainty, it can offer us a glimpse into a new world. A world beyond white-supremacist-capitalism.

Street art – in all its forms – are weapons in the struggle against oppression. In its most powerful, non-commercial forms, street art pries open the cracks in the brutal logic of capitalism to give voice and visibility to other ways of seeing and working with each other; our shared urban spaces; and the possibilities of the world we collectively inhabit. Whilst many forms or art are merely representations of justice issues, often produced and consumed in sites and spaces that replicate and further homogenize the worst values of neoliberal capitalism (as well as having no relation to grassroots struggles except via the representation-exploitation-commodification business model), more often than not, art in public space resides in a site where, as history shows us, power can not only be created from the ground up - but also shared with others.

Over the last decade, across the world people have been fired up by the transformative power of large-scale murals. This isn’t surprising because they create powerful images, and mural art has a long history in many parts of the world, none more so than in Asia, Africa and South America. Rooted in the social, political and spiritual histories of widely varying places and cultures, murals bring the visions, beliefs and realities of artists and communities to life, embodying what people stand for. Traditionally, the power to shape, control and change the narratives visible in public spaces was accessible only to those with wealth and power (think corporate and state propaganda, urban planning and the politics of architecture). However, the ability to communicate ideas and messages via large-scale images in urban spaces is now opening up.

(In 2016, AptART worked alongside young Muslim women in Jordan to create a series of murals to make visible the power and dignity of women in the region. Credit: AptArt)

As more and more cities embrace the benefits of street art, ideas about who has the right to author, shape and create stories in the city are slowly changing. Now, the faces and stories of normal people around the world rise up on huge walls, overshadowing corporate messages promoting artificial beauty standards and other lifestyle bullshit. This helps make the city a more democratic space, with a range of messages becoming visible, shifting our understanding of what cities could be in the future. I know these are small steps on a longer path but think about this: in the history of human civilizations – from the earliest beginnings of complex urban centres in Mesopotamia to a modern metropolis such as New York, Lagos or Busan – this has never happened before.

Murals have been a key form of cultural storytelling since humans first painted on walls. Five thousand years ago they appeared in ancient rock shelters painted by San bush people in what is now Namibia, Botswana and South Africa. Traditionally it was the role of the shaman to articulate visions in murals that represented the beliefs of the tribe. This was a form of power preserved and controlled by subsequent religions (and, later, by corporations) for thousands of years – think Egyptian tombs, mosques, Buddhist temples, Christian cathedrals and billboards. The artist painting murals today has power; the question is, how can this power be made more inclusive to ensure the voices of those who live in and around the city are heard and celebrated too?

(An early mural by Mozambique artist Malangatana Ngwenya painted in Maputo, Mozambique, 1969. Following independence from the brutal colonial rule by Portugal in 1975, murals began appearing on many walls in the capital Maputo. One of the most dramatic was the Heroes' Circle, a mural ninety-five meters long and six meters high. Credit: Malangatana Ngenya.)

Over the last century, many artists have risked imprisonment, or worse, to ensure that the histories and beliefs of local communities were seen and remembered: a product of the most fruitful period of the Mexican mural renaissance (the 1920s to 40s), Diego Rivera’s large-scale murals were a response to the social upheaval and reforms of the Mexican Revolution 1910–c.1920; in the 1960s, Malangatana Ngwenya, the Mozambican painter and poet, was arrested by the Portuguese colonial secret police and imprisoned (much of his art, including many murals, depict multiple bodies, crowded and struggling against the oppressive Portuguese regime); in the 1980s in Sri Lanka, during the attempted genocide of the Tamil people, murals were a key part of awareness-raising about the struggle; and, similarly, in Northern Ireland, murals chronicle the 30-year resistance to British oppression during the Troubles.

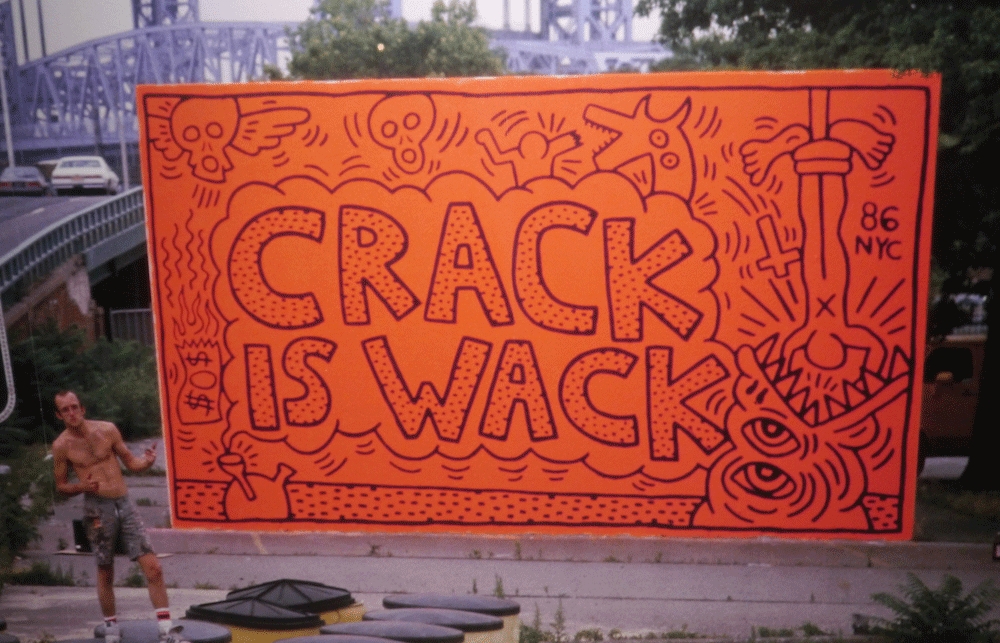

(Keith Haring in front of his seminal Crack Is Wack mural in New York City. The mural (from 1986), on a handball court at 128th Street and 2nd Avenue, was inspired by the crack epidemic and its effect on the city. Credit: Juan Rivera.)

In the 1980s, another marginalized (and, after his death in 1990, venerated) artist was working alone in the streets and subways of New York. Keith Haring was one of the greatest mural artists ever to have realized the complexity and universality of the queer experience. Drawing widely on the iconography of Aztec, Mayan, North African and aboriginal cultures, he was not only a founder of the early street-art movement, but also a prolific AIDS activist, working closely with activists from ACT UP and, later, the anti- apartheid movement. Today, graffiti and street artists all over the world are carrying on the tradition of social activism. This is especially true in places such as Tehran, Kabul and Nairobi, where artists risk physical violence and imprisonment each time they step out into the streets to paint large murals that challenge dictators, corruption or the social conditions of the poor.

When artists step outside with others to paint in public space they often break the law and trespass. This act of trespassing is a fundamental one that not only transforms the space, or situation, that people create art in, but also transforms their understanding of themselves and their relationship to dominant – yet often invisible – forms of authority, control and censorship that exist in the community. When most urban space is privatized, with strict limitations on forms of expression, the large scale mural can take agency over the look and feel, even the meaning, of the street. It is a subversive response to the oppressive nature of capitalism (which values spectatorship and the consumption of culture over active participation), a response that can be further amplified with the adoption of collective approaches and community-led processes.

By trespassing, artists and communities can push back against the systemic oppression and, in the process, disrupt the power relationships that are enshrined in the logic of capitalism. The large scale mural is a good gateway action. If people can work together to transform a wall in a neighbourhood, what else can they do collectively? The power of the large scale mural can rise above mere representation of social issues by adopting processes that can offer artist and community alike an experiential glimpse of another world. One that is often hard to find in the hyper-individualist culture we are indoctrinated into from birth. Like our ancestors of old, artists today have to help articulate the visions of communities as they ‘demand the impossible’, whilst having the courage to work with others to begin to create it, one street - and neighborhood - at a time.

Interview with Artist/Collective, AptART

Action/Project: Paint Outside the Lines, 2014-Current, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, US, Greece

Context for the Action

Paint Outside the Lines is an international street-art campaign highlighting the importance of inclusive and diverse communities. The campaign is an initiative of aptART (Awareness & Prevention Through Art), an organization of artists and activists painting with young people in refugee camps as well as areas in conflict and post conflict. AptART has been sharing creative outlets and amplifying voices of marginalized groups since 2010. Artist and activists have painted walls, implemented workshops and created exhibitions in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, the Gaza Strip, Syria, Turkey, Myanmar, Mozambique, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Greece, Belgium, France, Germany, Jordan, the United Kingdom and the United States. Bill Posters talks to Samantha Robison, founder of AptArt about the Paint Outside The Lines project about the power of a youth-led approach to mural art.

What did it feel like when you were preparing for this project? How do you involve the voices of others in your practice?

Preparing projects is always exciting: I get stoked about the transformation we are about to make with a community in their day-to-day experience of public space. When you paint a massive wall, you’re changing the cityscape. With aptART projects we also try to provoke thought about social norms or the status quo. To involve voices of others, we have a couple of approaches. Sometimes we partner with a local organization and get kids together and, other times, we just round kids up off the streets or knock on doors. After we get the kids together, we start talking about topics and how they relate to them. Then the kids get to paint their ideas directly on the wall as part of the larger concept.

What has been the best moment for you so far in this project?

The highlight of painting walls with aptART was in 2014 at Arbat IDP (Internally Displaced People) camp in the Kurdish region of Iraq. It was a time when Islamic State (ISIS) was gaining ground in Syria and Iraq. The camp comprised Christians fleeing Mosul, Yazidis fleeing the Mount Sinjar massacre and a few Muslim sects sprinkled in. The camp manager and community leaders asked us not to write a message in any language but to convey a theme of coexistence. We rounded up over 150 kids and each one painted their name and where they were from, or drew a picture, on a handful of bricks to represent themselves. Then we started shaping a city skyline from the bricks with all three religions represented: there was a Christian church, a Yazidi temple and a Muslim mosque. I waited until the wall was almost complete to add the cross, the minaret and spires, feeling anxious about the possible backlash. As I was finishing, a group of Muslim women stood beneath the ladder; one was looking very intense and shouting in Arabic. I thought this was it, that we would have to stop painting and address it. As I asked my friend to translate, she started smiling and said how much the woman loved it and how beautiful the idea was. That wall experience and that woman restored a bit of my faith in humanity. It’s in short supply sometimes.

What happened as a result of this action? What impact did it have?

People were pretty stoked on it. It gave kids from different backgrounds an opportunity to interact and play together doing something constructive. A lot of their time was spent playing a game of ‘Peshmerga versus ISIS’ as they threw rocks at each other and created cardboard shields.

How does it feel as a young woman to be working on these kind of projects in a male-dominated practice like street art? Any advice for other young women who may want to do something similar?

It’s certainly a man’s world and the street-art industry is no exception, but don’t let that stop you! Nothing is going to change unless we start shaking shit up. I think one of the more hardcore ladies I work with in street art is Jasmin (Siddiqui) of Herakut. She’s a strong personality and she always goes big. So I would say, ‘Go big ladies!’

Often your projects, in countries such as Iraq and Lebanon, have included working alongside trauma-informed or marginalized young people in challenging contexts. How do you ensure that your process is a meaningful one and is supportive to the needs of the group?

There is a whole practice and process that goes into art therapy and we’ve worked with art therapists on some projects in the Gaza Strip. I am always careful not to call what we do art therapy. Sure, it has some therapeutic elements to it, but it’s not clinical. We try to do as much research as possible and create concepts alongside the local community – the kids are involved in the process and their ideas are presented in a public platform. I think, for kids, having your ideas presented in a semi-permanent way in the public space, for everyone to see, is pretty huge. It does a lot for their self-confidence.

KEY PRINCIPLES:

Go BIG: make a massive, positive change for the people living wherever you paint and put some colour in their lives.

Communicate more than just your name. Start conversations. When you can, shake things up. If you can’t make people think, make them feel.

Scope your location. Ensure your wall is accessible, with no electrical wires, trees or other buildings obstructing your movement and that your cherry picker or ladder is relatively safe.

Understand the place, people and culture. Know your audience and know the cultural relevance of symbols so you don’t offend anyone.

Drop your ego. In a public space, you aren’t painting for yourself. Try to ensure the majority of the community can appreciate the concept.

The Street Art Manual is available now via BillPosters.ch