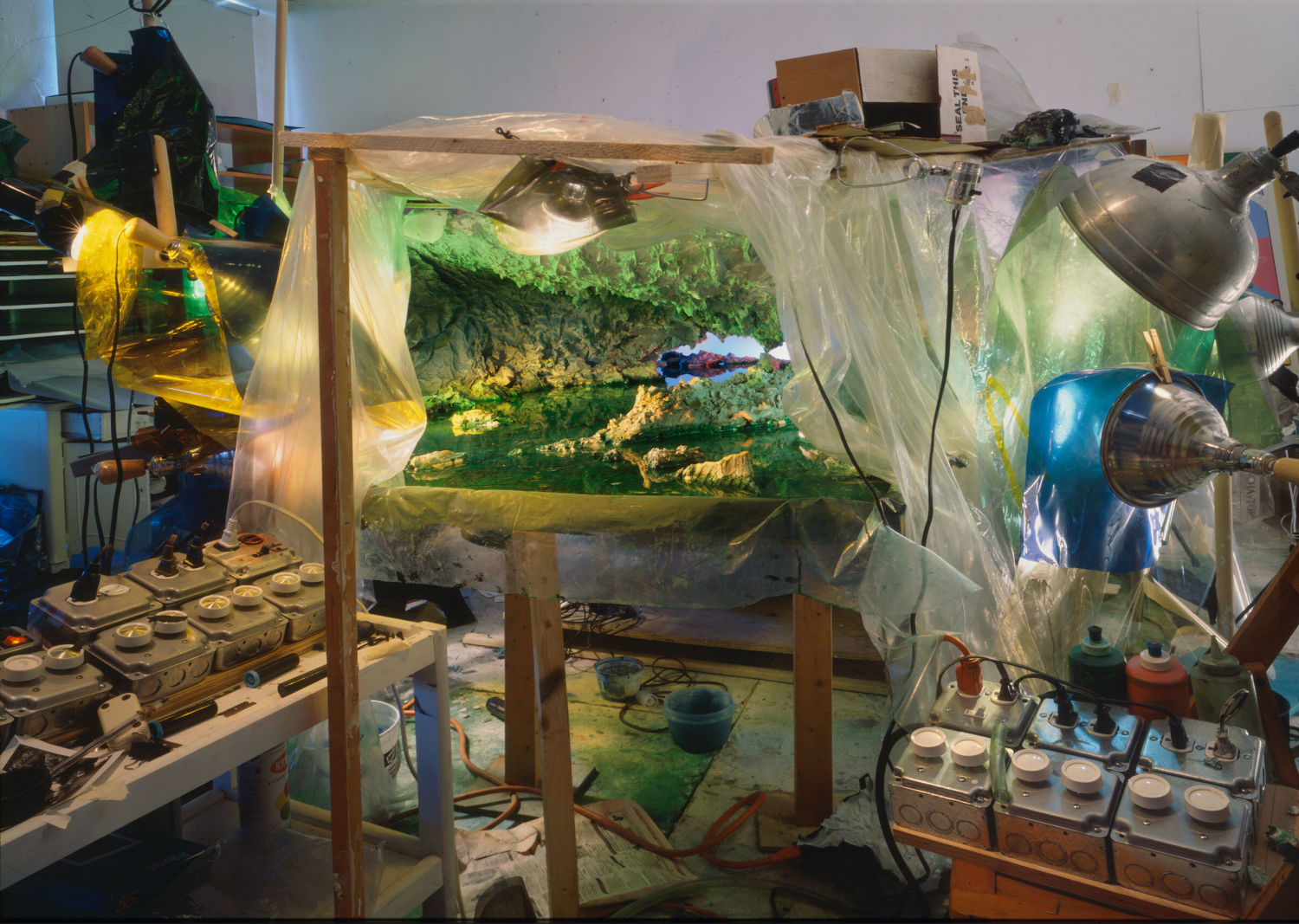

A spiraling staircase leads to Kim Keever’s studio/laboratory a few blocks past Tompkins Square Park in the East Village of Manhattan. Inside is a cavernous room, and on the day of my visit, dried pools of color and various dioramas were scattered across the floor. Half a dozen light stands encircled the laboratory’s center stage, a 200-gallon fish tank.

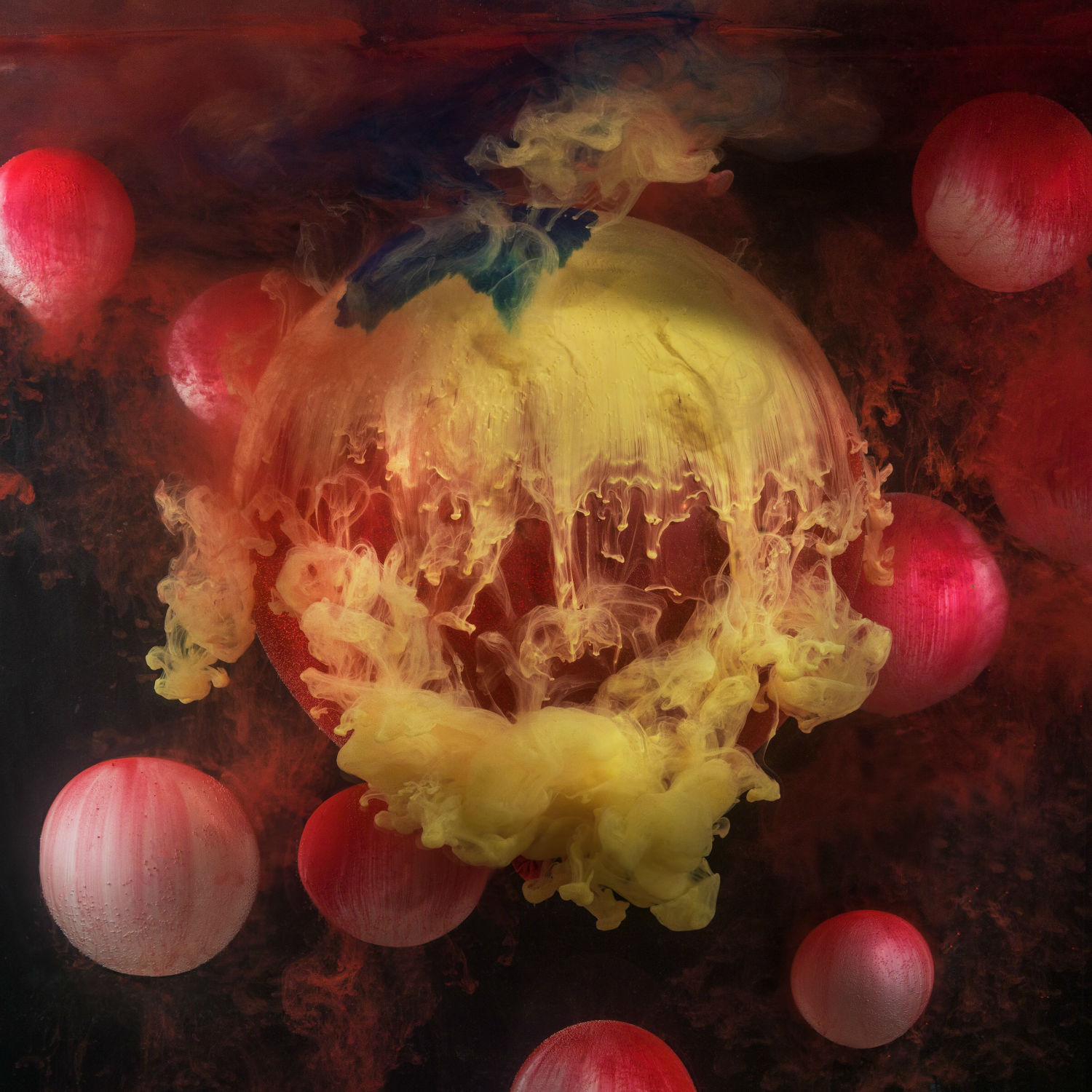

Kim’s medium-format Hasselblad sat on a tripod pointed at the tank, ready to document the shape-shifting, three-dimensional painting that would soon materialize. He began by squeezing industrial paint tints from repurposed liquid soap bottles into the tank. Drop after drop, color plonked into the volume as the camera clicked. A few small transparent green drops were followed by a darker blue, which dispersed and disappeared when subsumed by other color cascades. Each shade seemed to have its own magical transparency and flow diving into the tank. The liquid color bloomed into jellyfish and mushrooms of vibrancy. Ephemeral forms plumed momentarily amidst an otherworldly storm. In a few short minutes, this chromatic cloud turbulence dispersed, and everything settled into a muddy haze.

Kim proceeded to the computer station to view the hundred or so images snapped during the day’s deluge. From these digital captures, he zooms in and crops to accentuate compositional elements within the larger collage of cloud forms, explaining that, in a single pour, he might find seven or so usable shots that could potentially become photographic prints, generally released in editions of five in large and small format.

After a quick review and discussion of some of the more interesting moments that transpired in the tank, we settle into a conversation about his former life working in NASA laboratories and three decades of working as a full time artist in the East Village.

Read this feature and more in the April 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

David Molesky: How did you settle upon being an artist?

Kim Keever: I always made art, but I never really took it seriously, partially because of the influence of my father. My mother, on the other hand, was always encouraging. I finally reached a point in my life where I realized I only have one life to live. Maybe there are others, I’m not going to deny it, but I know I’ve got this life, and I know I really want to be creative and make more art. If I end up starving on the street, I can say I was an artist, and that’s what I really wanted to do with my life. I’ve reached a point where I have had some success, and I kid my friends by saying, “not bad for 100 years of trying.”

A hundred years of trying?

It’s so hard to make it as an artist is what I mean. It’s a hard slog for most artists.

And living in one of the most expensive cities for a while.

It’s true, but it’s the place to be, really, for an artist, isn’t it?

Yes, because there are so many opportunities for artists here.

And there are good museums and lots and lots of contemporary galleries. Serious collectors come to New York from all over the world.

Now that you are in a lot of contemporary galleries and museum collections, can you identify a point when that all picked up, something that contributed to you becoming more of a known artist?

I have gradually gotten into museums, but what really has made a difference for me has been getting my art out there on the internet and the new series of abstract images I started about three years ago. I simplified everything by just dropping paint into water and taking photographs from the front of my aquarium. As soon as I started this process, I thought to myself, this really works! It’s all so random and I feel like I am operating a painting machine. I drop paint and ink into it and the colors flow their own way. I can’t control it, really. If I try to stir it and move it around, it will go to mush immediately. As a result, I get a lot of very different images, and I am very happy with that. Recently, I have been putting fabric in the tank along with the paint and water. The latest series uses colored balloons in the tank.

Did you begin with the dioramas in the tanks?

That’s right, I made extensive dioramas first. I was a painter and I got bored with painting and wondered what I wanted to do next. I admired Cindy Sherman’s work because of the personal quality and started making tabletop dioramas of landscapes. I couldn’t get an atmosphere, so I eventually covered the piece with clear plastic. Then I started putting smoke into the space.

Like a fog machine?

Smoke bombs, lit cigarettes. I wasn’t smoking at that time, in any case. That worked in a way and it gave a kind of foggy look, but that eventually got old before I got the tank.

How did you get this big tank? Have you had the same one for a long time?

Actually, the one I’m using now is a 200-gallon tank. The one that I had before was a 100-gallon tank that I got from a friend. He was throwing it out, so it was perfect timing. And that’s when I had the idea of putting paint in the water to make clouds for the plaster landscapes I constructed.

So what year did you start doing the water tank?

I stopped painting in 1991 and started the tabletop photography of constructed landscapes, some of them involving pools of water, as in the Eight Months series. In 1998, I started working with the water tank.

Before you became a full-time artist, you worked at NASA, right?

Yes. I was going over there in the summers to work as an engineering intern. Later, when I was getting my graduate degree in engineering, I started working on a project at NASA. That’s when I made the absolute decision to drop out of engineering and become a full-time artist.

Is that the space you told me about with the strange cone shapes that silenced all the sound?

We were measuring fluid flow versus noise through different shapes of jet nozzles. I had never seen anything like it. We worked in a room that was 150-feet long by 150-feet wide, by 150-feet tall. The room had 4-foot cones that pointed at you from everywhere.

Even the floor?

Not from the floor, but on the walls and the ceiling. You would walk into the room and your ears would hurt because there was no sound at all, the room just absorbed everything. The project was about noise attenuation and what would make for a quieter jet engine for landing at an airport, for example. The testing was about the pressure to thrust ratio for various configurations of nozzles, but I really was not interested. One of the best lessons in life is to find something that you love to do and not something in life that Mom and Dad want you to do or that pays the most money, or whatever.

It’s like the Joseph Campbell saying, “Follow your bliss.” Although my parents would like to see me more settled, in the end, they say, “Do whatever makes you happy.”

I think it’s partially a generational thing too. When I was a kid, life was more prescribed by society and family. I think it has really loosened up a lot. And for better or for worse, we live in the history of our time.

There is such an enormous influx back into the city that there wasn’t before. I struggle with validating the high rent in the city and whether or not working in a more rural environment would be better.

It’s a real dilemma. If I left the city, then I would probably have a lot more space, but then I would gradually lose the connection to the art world here. I’ve gotten to a point where I have been here so long that I am afraid to leave. I think I would be so bored, even though I love the country, and I love the landscape. I believe that, as an artist, you stand a better chance to get a good foothold living in the city.

And I love my free time. I work and then I go out, and then I work later on. My free time helps me relax and I get my best ideas just walking down the street where there are no pressures.

That makes sense, like the concept from the Bhagavad Gita that, “From rest comes action.”

Ah, I’ve never heard that. Very interesting.

If you are always on the go, it’s hard to work optimally. It’s like a cell firing in the brain; you have to recharge so you can fire again. My parents used to tell me that I should get a normal job. But I would rather live frugally with some uncertainty than compromise time. I think, as artists, we try to maximize our experience of life. Our artwork makes life more beautiful, meaningful, and worthwhile. We are selective of how we use our time and who we interact with.

Engineering, of course, is a part of science. I didn’t find those people very interesting. One thing that you can say is that science involves a very different set of tools. The tools are a lot more complex and take a lot of studying to understand. In general, it would be very hard to learn science on your own. As an artist, you have a kind of freedom. You don’t really need to go to art school to be a good artist. I find artists much more interesting. I would rather go to a party with artists than one with non-artists. I’d get bored quickly; with artists I am much more relaxed.

Yeah, it is really wonderful. Between artists, there is a common language that rides beneath the diverse materials we work with. Here, we can relate to each other in a profound way, and that accelerates our ability to get to know one another. I think that an important component of happiness is feeling a sense of connection to people.

I agree, and I think of art as the visual connection to the world. Like Picasso, I am always amazed by little kids’ drawings. Every kid makes great drawings, and I think, where did that come from? Most people lose that ability or quality of connecting vision with their hand. They tend to lose their relationship to art as they grow older. I can look and look at a sunset and I am in love with the sunset. I don’t know if everyone can do that. I don’t know if other people necessarily feel this kind of connection. I think they might think they do or think they should.

There is a fable about a farmer who proudly shares his sunset painting with a guest. They go outside and see an actual sunset. His guest asks, “If you have the real sunset, then why would you need the painting.” The farmer explains how the painting has taught him to experience the sunset’s beauty more deeply.

Also, the ephemeral quality of light and sunsets as we go through life, which, in the painting, is a moment that is captured by an artist. It is a relationship to a person like ourselves who has done something that conveys a feeling or an idea to you that you might not be able to accomplish by yourself. And when it’s a really good painting, it’s a beautiful experience to observe that painting and be mesmerized by it, by what qualities it has.

I sometimes think of art like a sort of pre-masticated visual experience, passing through the human nervous system of someone dedicated to a particular vision. The essential elements are heightened and all the distracting ones that don’t support the vision are diminished.

It is another connection to the world. I have heard that one third of the people love art, one third hate art, and one third just don’t care. I am always interested in that third that loves art.

It’s really nice to meet those people because they are the ones that support us. It is also gratifying to meet those people who are on the fence and help them over to our side.

It’s kind of an odd and lone profession. It relates to being a monk in some sense. Art is like a monastery. You associate with other monks but spend a lot of time meditating about your art and making your art.

Right around when I first saw your work, in 2005, I was into the Tang Dynasty poet Hanshan. He was a mountain hermit who wrote poems on rocks and trees. Sometimes he would meet with other painters or poets to drink and discuss their mutual love for the moon. I gleaned from them a romantic sense of artistic practice as the worship of natural beauty.

Hokusai wrote something I was really amazed by. Basically, he was saying that up until age 50, he was making okay paintings, then he studied more and observed more, and by 60, was able to get the essence of the twig with its leaves; by 80 he was able to catch the flight of a bird, and he continued. By 140 years old, he finally got to a point of being a real artist. I was so impressed; I felt like it was such an amazing way to live.

Kind of like Malcolm Gladwell’s book saying that if you want to be an expert in anything, you have to do it for 10,000 hours. The longer you dedicate and focus, the more able you are to try new things and improve your vision.

There’s something about repetition that when you go through the 10,000 hours, you go through certain processes to achieve what you are trying to achieve. If you are sincere, you tend to get better and better. Eventually you become the best in the world at what you are doing because you are the only one who has gone so far out on a limb.

----

Originally published in the April 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.