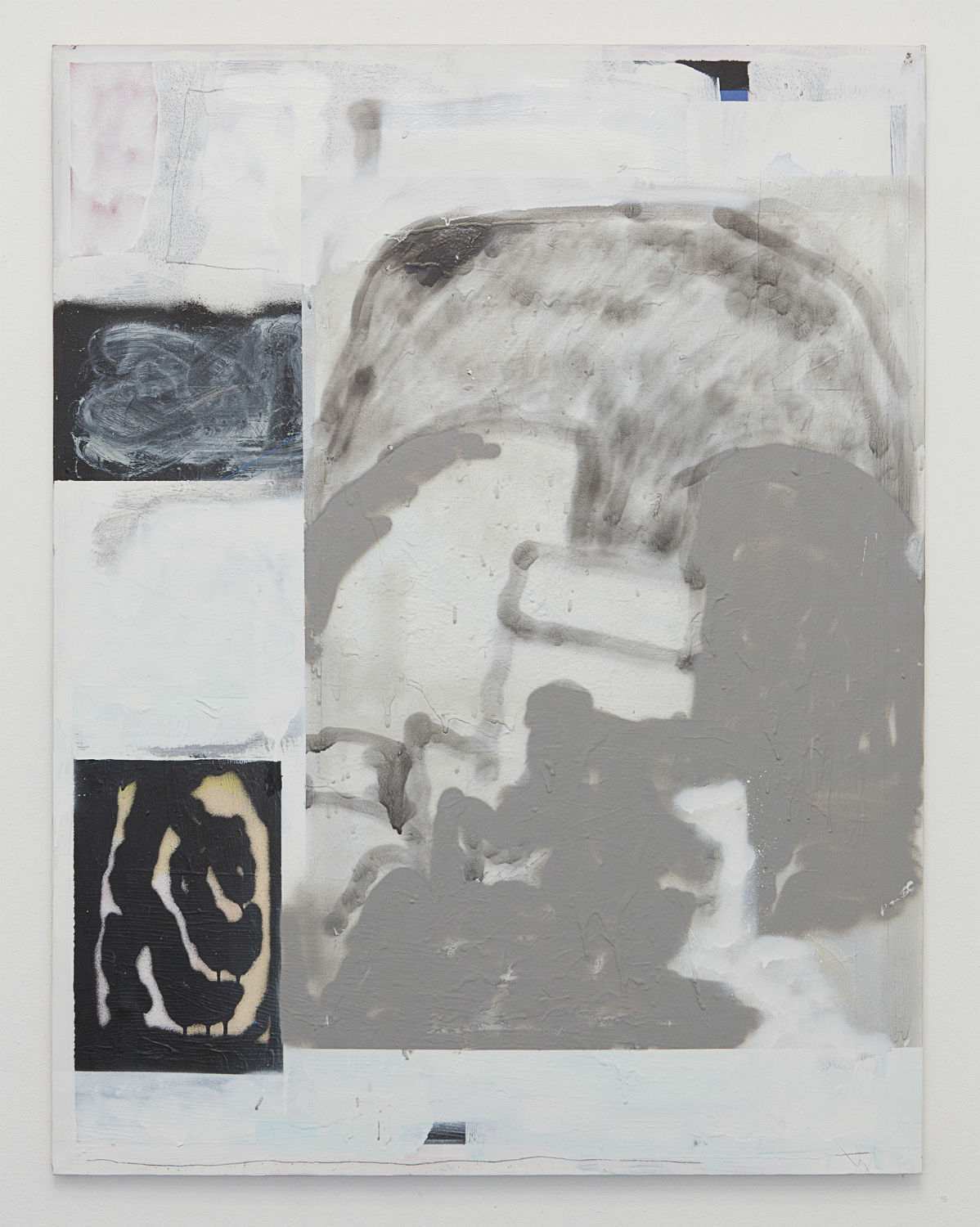

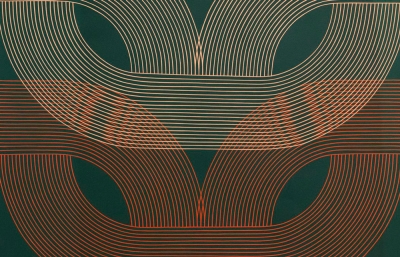

When Ekta, aka Daniel Gotesson, lets the subconscious dictate his process, total destruction is the only solution. Adding and erasing is integral, and he finds most of his magic in mistakes and restrictions. It ain’t easy to make abstraction resonate, but Ekta maintains purity and meaning in his expressions by being limber; staying in shape to make great shapes.

He ensures that almost nothing is literal and everything is spontaneous. A staple of the friendly art scene in Gothenberg, Sweden, he works best in good company, and he is at the top of his own game—with rules that only he could make.

This is an excerpt. Read the full interview in the August, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Kristin Farr: What do you think makes abstraction unique and meaningful, and have you always been able to make it work?

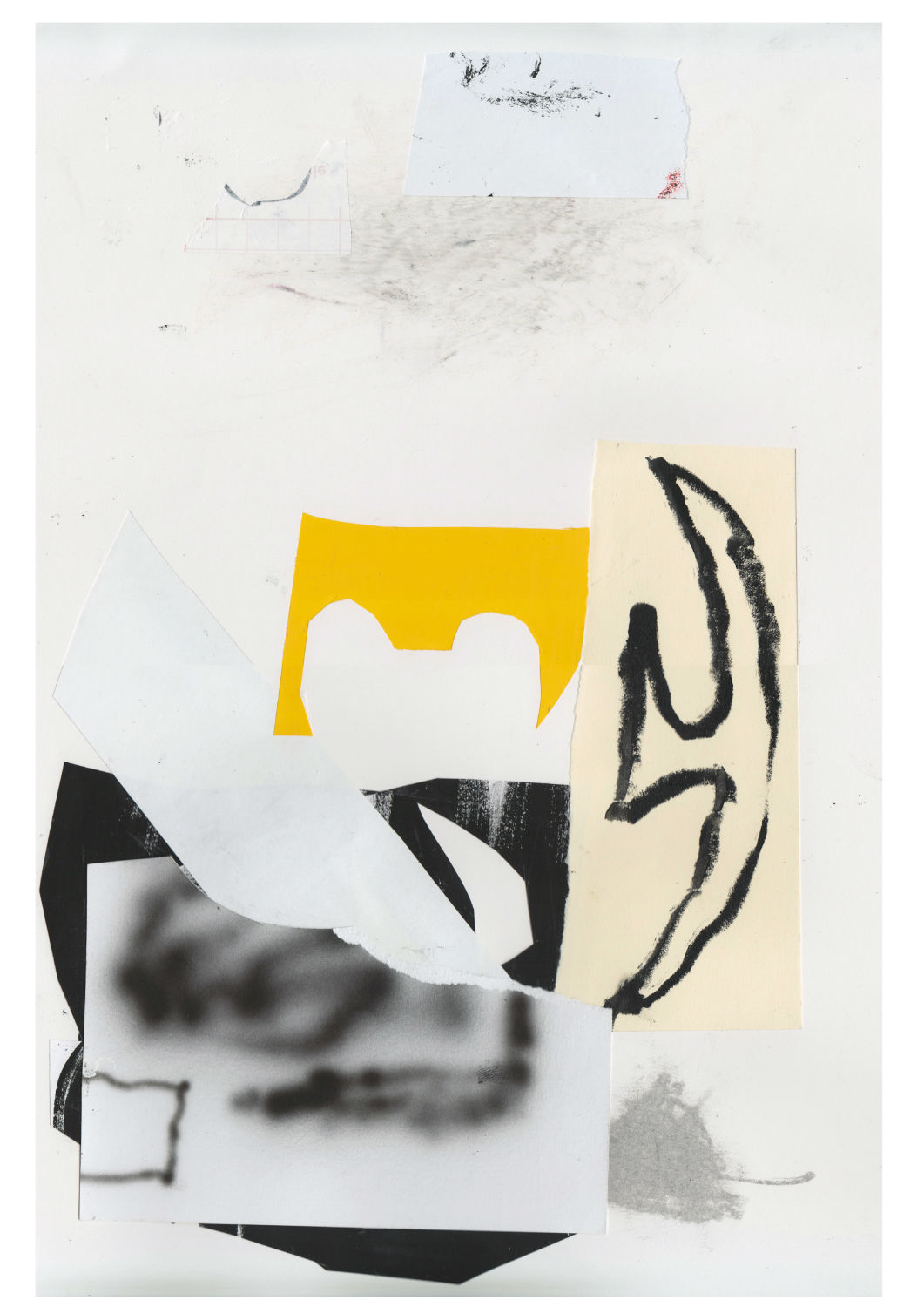

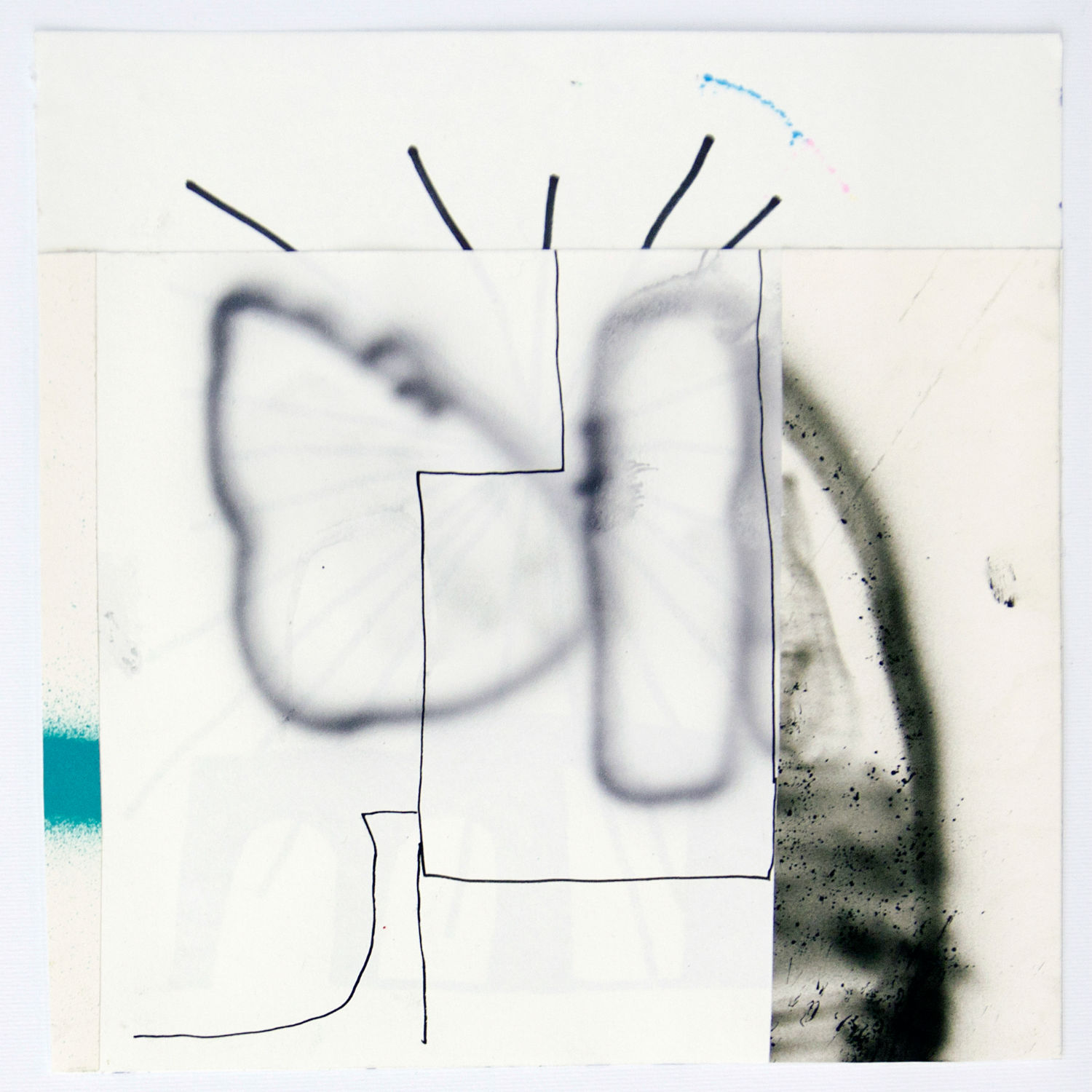

Ekta: I think I had some vision of what I would like to do, but it took time and many detours to get there. I felt I had something to prove to myself before I could move on. Initially, my work was more illustration-based, and I wanted to move more towards painting. In recent years, I’ve gained the confidence to have a more free approach to my work. I don’t like to be stuck with the idea that the sun is round and yellow; it might as well be square and blue. My ambition when starting to work on something like a drawing, painting or collage is to surprise myself and have a playful approach. I value mistakes and accidents, and things usually start to get interesting just after making a big mistake, either with what is left after you take it out, or what appears when you start to work around it.

You’ve mentioned liking the aesthetic of buffed graffiti walls, and I always notice them too. The buff makes abstraction. What are some other everyday abstractions that influence you?

I like broken stuff. An object that broke and has been discarded turns into something else. It ceases to be what it was, and you’re free to apply any content to it. I’m not really collecting things I see in the streets. I just document them and leave them as they were. Buffing removes but can also add, and I find that useful in my process. Taking out is also putting in. I prefer the traces of graffiti more than the actual pieces, and often I feel the same with what I do. If I add something to a surface, I find it works better when it’s covered. I work in layers, adding, erasing, adding, erasing. So I can relate to both the process of the buff and the aesthetics.

Photos by Per Englund

How do you maintain the purity of expression in your practice?

I need to be working continuously to build or keep up a flow and confidence in order to feel like I have a free process. I like working fast, as I’m restless, and I find that restrictions are a good thing for me. I sometimes set a format or just decide to work with black and red. So, for me, restriction opens up a lot of fun possibilities, as I have to make fewer decisions. Sometimes just making marks on a surface is enough. I feel that many of the decisions you make when working are not really important. For me, it’s more important to maintain a rhythm.

Do you consider everything to be part of an ongoing body of work?

Yes, an ongoing work that I’ll never complete. There is no goal in the end, and that’s what keeps me interested. It’s likely I will die with the feeling of having a lot left to do.

What else gets you creatively motivated?

I guess most people want something to do, and this is what I want to do. I try not to spend so much time thinking about why and how. I feel that could be a trap. I’m not of a conceptual nature, and I need to just find my way forward through painting, drawing, etc. I get motivated by working. When leaving a series of works behind, there are so many threads you want to pick up and follow. There is always something left to explore.

How did your life as a skater contribute to your life as an artist?

I’m not sure I would be an artist today if it wasn’t for skateboarding. It made me realize you can do pretty much what you want, and that personal style is more interesting than technique. That culture was my real education in music, art and so many other things. When I messed my foot up, drawing and painting took over, and I went fully into that. I don’t miss skating that much, but I miss hanging out in the street all day, all the crazy shit going on around you.

I heard you were inspired by the art section in Thrasher. Who were the artists you got into from that?

From very early on, it was Neil Blender and Mark Gonzales, and works from them still mean a lot to me. I have a couple of words or drawings from Gonz that got stuck in my head like, ”Vomit on the steps. Call the next day to apologize.” I don’t need to take it apart, and I don’t care to try and figure out why I think it’s so good. I just love that.

Where are you based and what is your studio like? What’s a typical day for you?

After nine years in London, I moved back to Sweden in 2005 and settled in the city of Gothenburg, and I’m still here. I share a big studio called ORO with six other artists, and I really enjoy having people around when I’m working. I have my own studio, but we also have a large room that we share where you can work on large stuff. On a regular day, I drop my kids at school, then go to the studio and spend 30 minutes with emails and stuff like that. If the weather is good, I try at least once a week to go out and paint a wall, and after that, I have a few hours left in the studio before picking up the kids in the afternoon. If I have a night off, I might go back to the studio for another couple hours of work, or go see an opening, or meet friends for a drink and a smoke.

What do you feel are the most significant differences between painting outside and in the studio?

I’ve been dealing with that a lot recently. Last year, I found a flow in painting uncommissioned walls, and I really wanted to try and find that feeling when working in the studio. I know the circumstances are not the same, and that it would be stupid to think it could be the same process, but I’m interested in how close to it I can get. Painting walls outside, for me, is superior to any other process. It’s as free as I can get at that moment. To get close to that in the studio, I need to make restrictions for myself. Working on several things at once can also help. When I’m painting a wall outside, I’ll be done in less than two hours. In the studio, it can take days to get anywhere, and sometimes feels like the process is just a series of failures. But a failed painting can be more interesting than a painting that is too good. I value risk, and when stuff comes too easy, it means you’re not taking enough chances.

For more information, visit ekta.nu

----

Read the full interview in the August, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our webstore.