About 45 million Americans have at least one tattoo, although it may seem like even more if you live in the Bay Area. A comparable craze for full-body tattoos swept Japan's 19th century cities, nowhere more than in trendsetting Edo (modern Tokyo). Tattoos in Japanese Prints, an exhibition on view at the Asian Art Museum from May 31-August 18 2019, recounts how large-scale, intricately-Inked pictorial tattoos — what we now recognize as a distinctly Japanese style — emerged in 19th-century Japan in tandem with woodblock prints depicting tattooed heroes of history and myth.

With more than 60 superb works from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston collection, Tattoos in Japanese Prints uncovers the complex interplay between ink on paper and ink on skin, revealing the origin of some of the most world's enduring and popular tattoo motifs. The exhibition traces these designs to a famous set of prints by artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861), a series which was itself inspired by a popular 14th-century Chinese martial-arts novel.

“By putting the aesthetic genius of Japanese printmakers on full display, this exhibition underscores how the popular culture of late Edo-period Japan continues to influence how we express ourselves today,” says Jay Xu Asian Art Museum Director and CEO. “We’re excited to share such eye-catching prints with every kind of visitor: from collectors and connoisseurs familiar with the technical virtuosity of these artworks, to audiences who want to understand more about the surprising history of their own personal ink.”

While searching for new subjects for his prints, Kuniyoshi hit upon the idea of a print series focused on hero-bandits from the famed “Water Margin” tale, which was first translated from Chinese and published in Japan between 1757 and 1790. Kuniyoshi called his series, published in the late 1820s, One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Water Margin. Significantly for the history of tattoo art, Kuniyoshi gave many of the heroes elaborate tattoos, even if the original text did not mention any inked embellishment on their bodies.

“Tattoos in Japanese Prints lets museum visitors see how creative ideas flowed from popular art into urban life, and back again,” says Laura Allen, Asian Art Museum chief curator and curator of Japanese art. “Scholars are uncertain whether Kuniyoshi's series kicked off the 40-year tattoo boom that followed, or if a nascent fad for body art prompted Kuniyoshi’s artwork, but the ample prints we have from this period by Kuniyoshi and others, who freely imagined elaborate tattoos, probably both inspired and reflected the real-life trend.”

Prints Showcase Tattoo Symbolism, Interplay with Kabuki Theater

Tattoos in Japanese Prints explores the historical context for the novel iconography introduced by Kuniyoshi and other celebrated artists, including Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864), Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), and Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900). These designs came to adorn the bodies of real-life Japanese urban men, both laborers and dandies. Many popular motifs of the time—lions, eagles, peonies, dragons, giant snakes, swords, and fierce figures like the Buddhist deity Fudo Myoo—remain part of the lexicon of Japanese-style tattoos today.

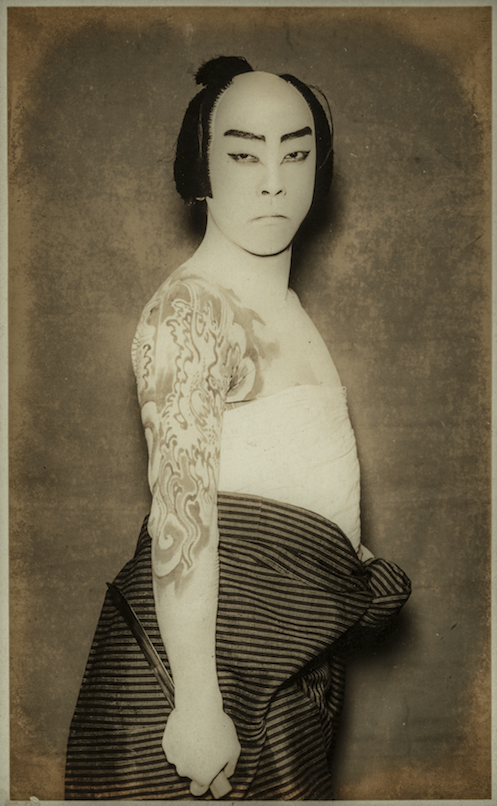

The fad for tattoos was also inseparable from the kabuki theater—Japan’s popular live-action dramatic form. Woodblock prints of the time both document tattooed heroes in known kabuki plays, and inventively went beyond the actual plays to feature the likenesses of prominent kabuki actors in imagined roles or off-stage moments where they sport elaborate tattoos. The resulting artworks combined emblems of bravery, valor and strength with the potency of celebrity, and the exhibition devotes a section to the intertwined popularity of kabuki and tattoo imagery. Several of the prints feature surprising gender-bending and fantasy elements that highlight the essential playfulness of the artists and the sometimes-whimsical nature of the genre. Cross-dressing was a tenet of kabuki storytelling since female performers were forbidden on the stage, and in real life actors were never tattooed—in performances they wore painted tattoos or close-fitting garments decorated with tattoo designs.

Intriguingly, scholars speculate that early tattoo artists might have been woodblock cutters from the printing industry. These artisans would have honed their skills transferring a two-dimensional artist’s drawing to the three-dimensional surface of the printing blocks: a short jump to the equally dynamic surface of a human body.

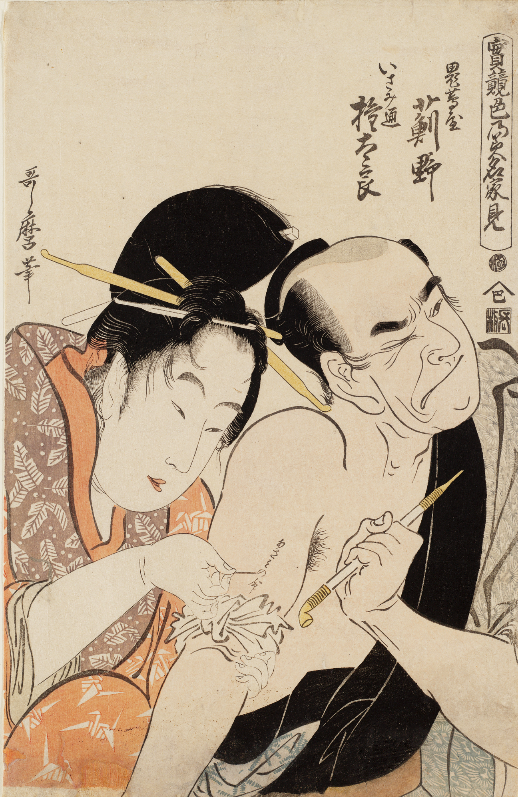

Tattoos in Japanese Prints sheds light on the history of tattooing by presenting examples of the much smaller-scale tattoo practices of previous centuries—declarations of religious devotion or the inking of a sworn lover’s name (as in a painfully realistic print [1798-99] from Kitagawa Utamaro [1750s-1806], or in selections from two erotic books included in the exhibition). These more modest tattoos bookend the vogue for elaborate body art in Japan, which ultimately lasted only for about forty years, until the early Meiji period (1868–1912). At this point, the Japanese government, considering tattoos “old fashioned,” prohibited them as part of its effort to modernize the country. Officially suppressed, tattoos slowly became associated with gangs and the criminal underworld.

“With the official suppression of tattoos, artists largely stopped designing prints of tattooed figures. The woodblock prints in this show survive as some of the best documentation we have of real-life tattoos in 19th-century Japan, and arguably they played a role in ensuring that these motifs endured,” explains Allen. “Despite the government’s wishes, foreign tourists, as well as navy and merchant sailors visiting Japan, were intrigued by local tattoos and found multiple channels for carrying them home. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s collection shines a brilliant light on the creative network of artists and artisans that inspired them.”

Tattoo imagery continued to be memorialized in reissued prints, on new photographic postcards, spotted on men who had received their tattoos before the government ban, or was inked directly onto visitors, and a longstanding global fascination with—and deep appreciation for—Japanese tattoo design was ignited.

“From the world-famous tattoo artist Don Ed Hardy to the home-grown inkers in San Francisco’s Mission District, great tattoo art and Japanese design share an indelible connection,” continues Xu. “We are delighted to flesh out this fascinating moment when art turned into life and life into art.”

For more information, visit http://www.asianart.org