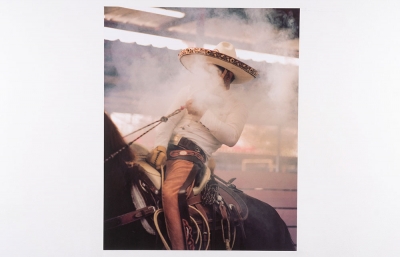

Throughout her illustrious career, spanning diverse corners of the globe from Kazakhstan to South Africa and the French Basque country, Anne Rearick has consistently used her lens to unearth the stories of communities often overlooked.

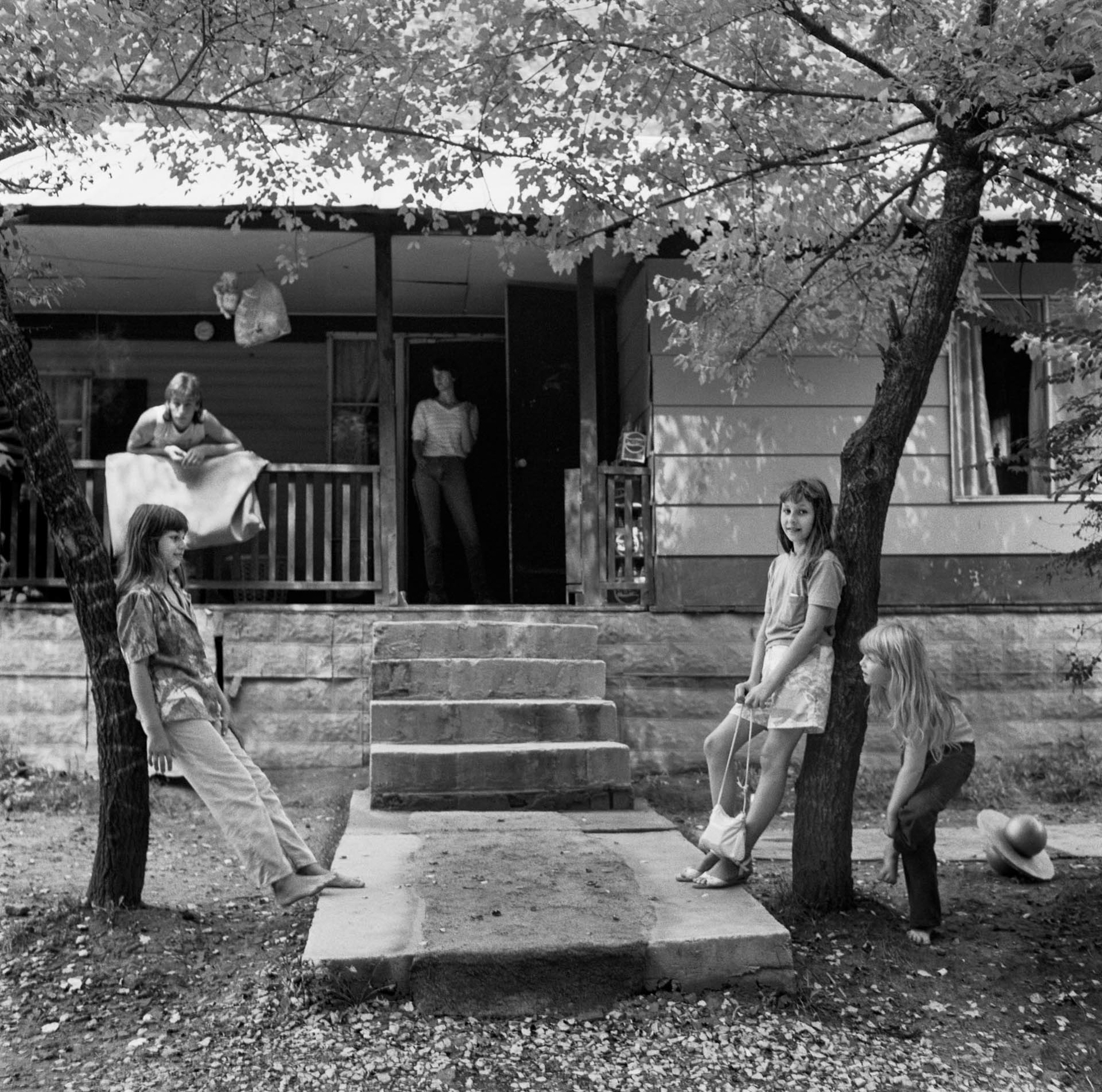

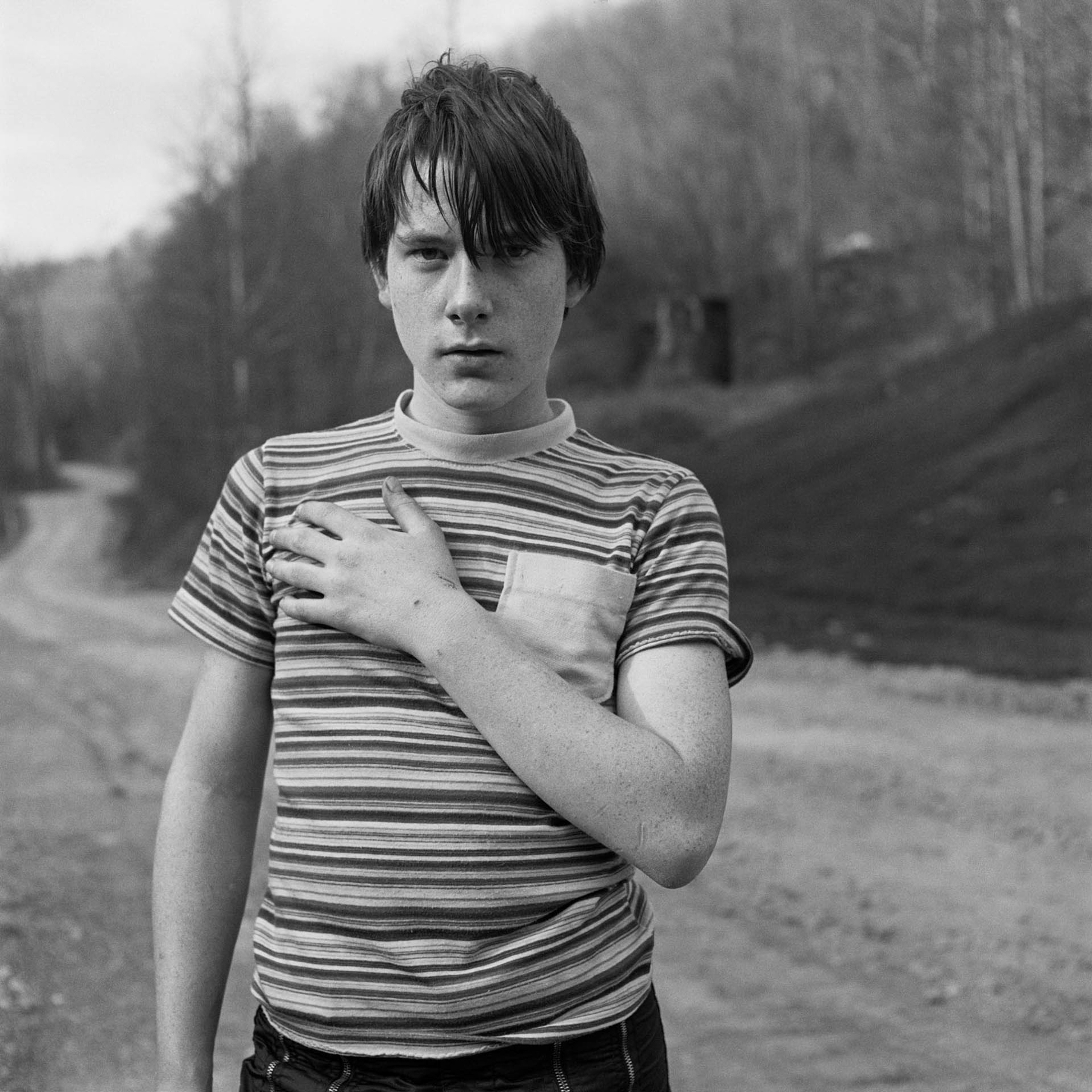

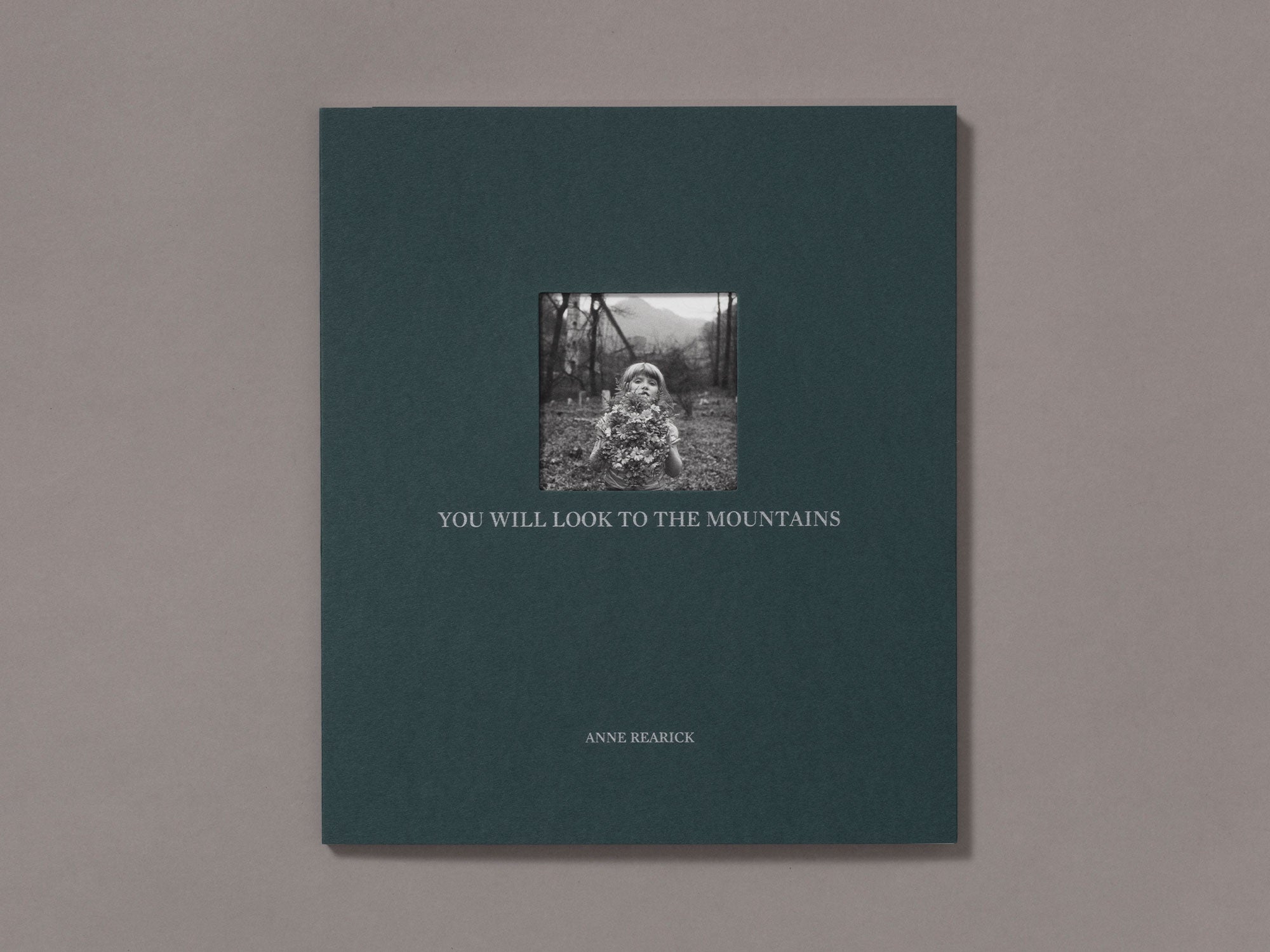

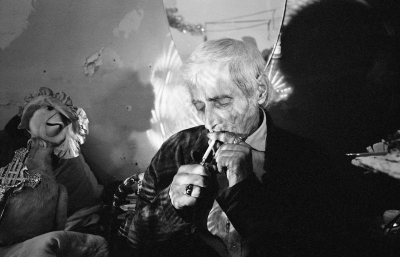

In her latest monograph, You Will Look To The Mountains, published with Deadbeat Club, Rearick revisits a brief but formative photographic journey spent in the heart of Appalachia. This project, now 30 years old, captures the raw and unadulterated essence of life in Perry County, Eastern Kentucky. These images, marked by their unvarnished sincerity, eschew sentimentalism, laying the foundation for Rearick's enduring humanist vision that continues to permeate her work.

Rearick's distinctive approach to photography is as much a documentarian's pursuit as it is a deeply personal endeavor. She is deliberate and methodical in her craft, often investing years to build profound connections with the people and places she photographs. Through You Will Look to the Mountains, Anne Rearick invites us to explore not only the Appalachian region but also the evolution of her own artistic identity—a testament to the transformative power of photography as a medium for understanding, empathy, and the universal human experience.

Alex Nicholson: Can you share what led you to revisit this work in Appalachia from over 30 years ago for your new book?

Anne Rearick: The idea to revisit the Appalachia work came from Clint Woodside at Deadbeat Club. I wasn't confident there was enough there as I had only photographed for eight days. Usually, I devote years to a project; in Basque Country, I spent 14 years photographing each time I visited. With South Africa, it was 12 years (2004-2016). I think after we selected the images and sequenced them, I grew more confident that there was something in the pictures that was beautiful, interesting, and different from other contemporary depictions of the area.

How did that early experience of working in Appalachia shape your artistic perspective and influence your subsequent work?

Appalachia was a foreign country for me. I even had trouble understanding the strong dialect! I knew then, as I know now, that my interest lies in telling stories of survivors, not victims. I want to find, through my pictures, the universal qualities that we share, no matter where we live and what our socioeconomic status is. In Kentucky, it was the unwavering faith, the strength of friendships and family.

You've spent a whole lot of time photographing in other places around the world. When you first started to spend time in Appalachia, did it feel foreign to you in the way these other places did when you first arrived? What were the differences between connecting with the people there and connecting with people in other places?

I was born in a small town outside of Boise, Idaho. My parents were very young, and when I was four, we moved to Massachusetts. After that, my mom moved my sister and me back to Idaho and then onto several other places. I attended 7 schools between kindergarten and my senior year of high school. Although it was difficult to change schools nearly every year, I think I learned to stay open and adapt quickly to new places. Appalachia was the first place that I experienced extreme rural poverty. I was very aware of the power imbalance between myself and the people I photographed and was grateful that they trusted me and allowed me into their community for this short, intense time.

Could you share any memorable or poignant moments from your time with the Riddle family that left a lasting impact on you as a photographer and as a person? Can you share the story behind the image on the cover and its importance to the overall narrative of the book?

I fell in love with the little girl on the cover, Amy. I found out when I was there that her mother was abusive and had abandoned her in their trailer. She left her with a broken leg. I think Amy was only four. Rachel, Amy's grandmother, rescued and brought her to live with her. My grandma rescued me too. Amy was the center for me. She was maybe only 8, but she had already seen too much. Her face was so beautiful and open. There was an innocence and a knowing that strangely reminded me of Marilyn Monroe. On one of my first days in Slemp, Amy took me to the family cemetery. She set about arranging the fallen artificial flowers on the graves and reminding me that this or that person was dead. Walking home, I launched into a full-on Elvis version of Heartbreak Hotel, and Amy sang along, swiveled her hips, and danced down the middle of the road.

What makes an image successful for you? What are a few things you look for while you are shooting, and do you find that changes when you are editing?

A successful image is one that expresses a moment of collaboration and trust between myself and my subjects. They feel comfortable in who they are and what they are presenting, and I strive to be direct and honest in our encounters and also in the pictures. I'm a sucker for formal beauty, and if the photograph has strong formal elements, it can only make the picture better. Although sometimes my pictures are awkwardly framed and not balanced in composition, the subject is so amazing that it doesn't matter!

What kind of effect has working in photography had on you as a person? Do you think the practice changed who you are at all, has it revealed or strengthened aspects of your personality/self?

I think a life of photography has been a real gift. Just by virtue of holding a camera, I have been welcomed into communities and cultures that I only dreamed of as a child. Photography has empowered me to trust my instincts, strive to be more authentic, and honor my empathy.

You Will Look to the Mountains is available via Deadbeat Club.