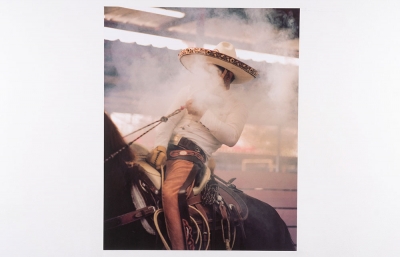

Featured frontally here are young women, each caught in a significant, quasi-cinematic pose; flowers in vases, cropping up to intrude on human activity; art books, shoes and fabrics scattered on the floor; statues and ceramic figurines competing for our attention with the models; easels and sketchbooks, as well as a standing oval mirror that may reflect one of the canvases against the walls. Plus the moveable furniture, chairs and tables, where a young woman may sit, or the ladder, platform, and staircase where another may stand, the better to see or be seen. Finally, there is the window-wall in the rear plane, translucent or, when open, giving onto a river and barges.

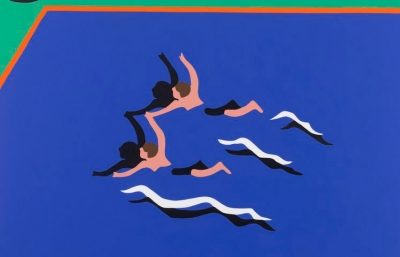

As in certain overbrimming films of Arnaud Desplechin, whom she favors, such a copious jumble of elements enlivens her work; competing colors and technique (fine-grained or deliberately unfinished) produce a rhythmic undulation of attention in the viewer who must hold one element too many in eye and mind. We are given cues: bright, crisp forms in the foreground lead the eye toward the murkier ambience further in, where inchoate daubs are still coming into existence or focus. Flowers may be reflected literally in a nearby mirror while their colors reappear on a blouse or canvas at the other end of the studio. Iliatova sets paintings within her paintings, each a discrete attraction, but often blurred like the images on the mirrors, or the gauzy statues. Together with the often ‘unfinished’ human models, all these discrete forms are staged to look toward or turn away from one another as in some modern dance.

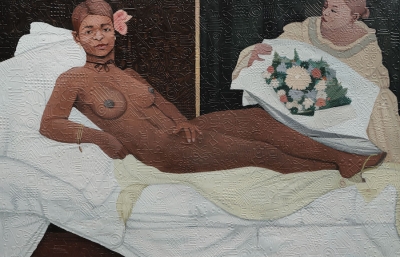

In earlier paintings going back more than a decade, young girls were often positioned amid trees or beside ponds and rivers, always implying enigmatic narratives, like film stills. Later works incorporated theatrical, even operatic scenes in nature; these are Vera Iliatova’s fetes champetres that update her idols Watteau and Manet. Later still came a series in which vegetation and particularly flowers overwhelm human dramas and architecture. All the while she has steadily come home...to her studio where all these elements reside and where The Drawing Lesson fully takes place. For she has never been a plein air artist. The flowers are now in vases; the models are deliberately posing; the books, loose pages, clothes from a wardrobe and other props all properly belong to her studio where, outside, barges make their way up the river. It is here in this real space that a fictional “Drawing Lesson” is offered, different each time.

The center of that depicted place, the dead center of each canvas, is devoid of objects, but not of paint. The nearly bare grayish floor, however, requires as much paint as do the brighter things that spread out toward the walls of the studio at the edges of the canvas. Depending on the day’s light, the floor of the painting may tend toward cool blue-gray or warmer taupe. Dull but polychrome, this floor, a stand-in for the artist’s palette, comprises several hues that are mixed there then applied, it seems, as an undercoat that delicately mutes the tones of the entire work. This harmonizes the more distinct tones radiating from the quaint dresses, the cut blooms, and the pages from art books (Matisse’s The Piano Lesson for one). Look at A Trance, Reversal; though organized into three intricate vertical panels, the figures and forms interact as a single imagined place of art-making.

Initially at sea within such busy works, our eyes quickly fix on the young women who themselves are both busy and solitary, as when they pose for a painter, also a model, within the painting. On one occasion the oval mirror holds the reflection of the painter, à la Velasquez, and the studio’s four walls close so that we feel contained within the space of creation. This is the genuine space of all these works, the place where abstractions arise from tangible materials, and where anything that might be represented--the outdoors, or history, or fantasies—must originate. Iliatova has represented such scenes in the past; this time she renders the place of that rendering. Here geometric conundrums tantalize us all the more because produced by nothing other than palpable color swaths sometimes fine, sometimes rough. The studio houses the originary act of painting; it is also where the history of art lives, at times literally, as when a Watteau print or the corner of an art book edges into frame.

Like Eric Rohmer and Hong Sang-Soo, two filmmakers she often revisits, Iliatova has always shuffled an attractive set of characters, incidents, gestures, settings and props into intricate configurations (incipient plots) that surprise viewers with effects that are specific to their art (in their case cinematic, in hers, painterly). This time she distributes and concentrates everything within the site where that shuffling has always occurred, in the studio. Essential Iliatova, The Drawing Lesson gives us all a viewing lesson we won’t want to forget. —Dudley Andrew, February 2024

https://nathaliekarg.com/