Harper’s is pleased to present two solo exhibitions in Los Angeles: Stacy Leigh’s Under New Management and Todd Bienvenu’s Rabble Rouser. Together, Leigh and Bienvenu invite us to challenge gender roles through their naughty, raunchy, and humorous figurative paintings.

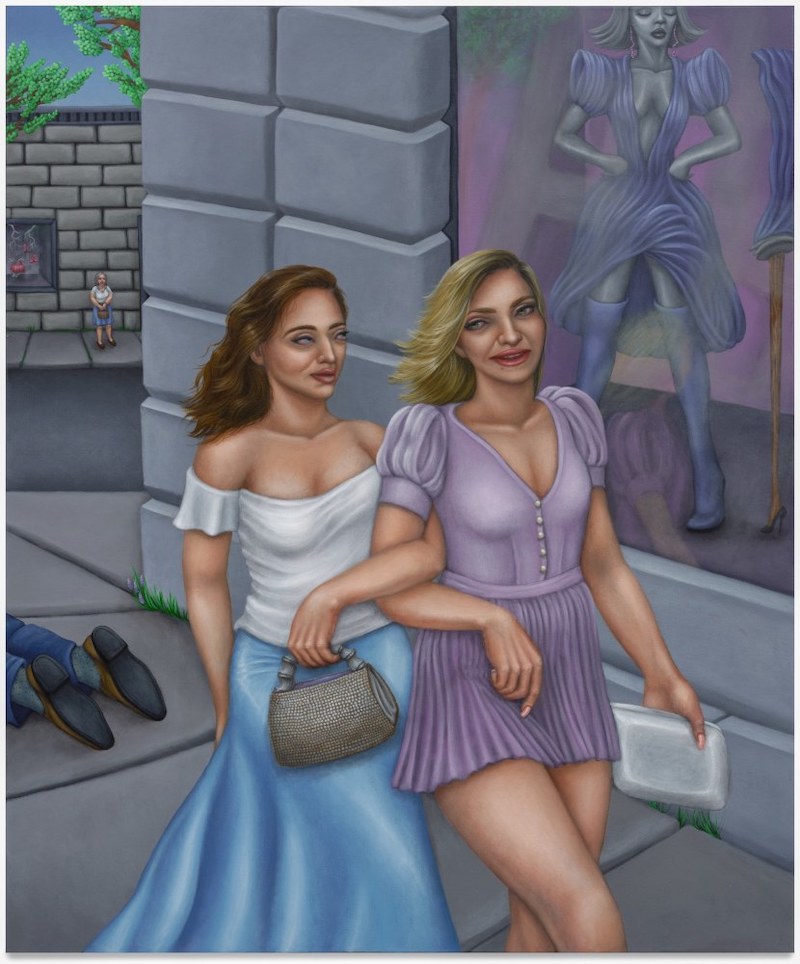

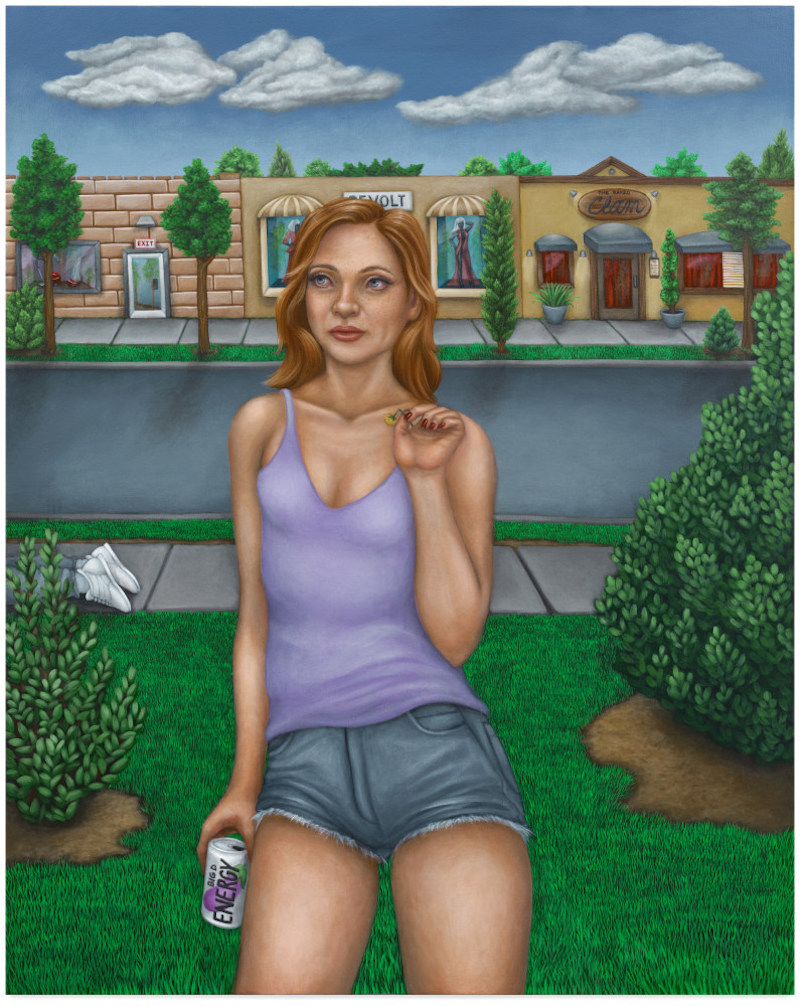

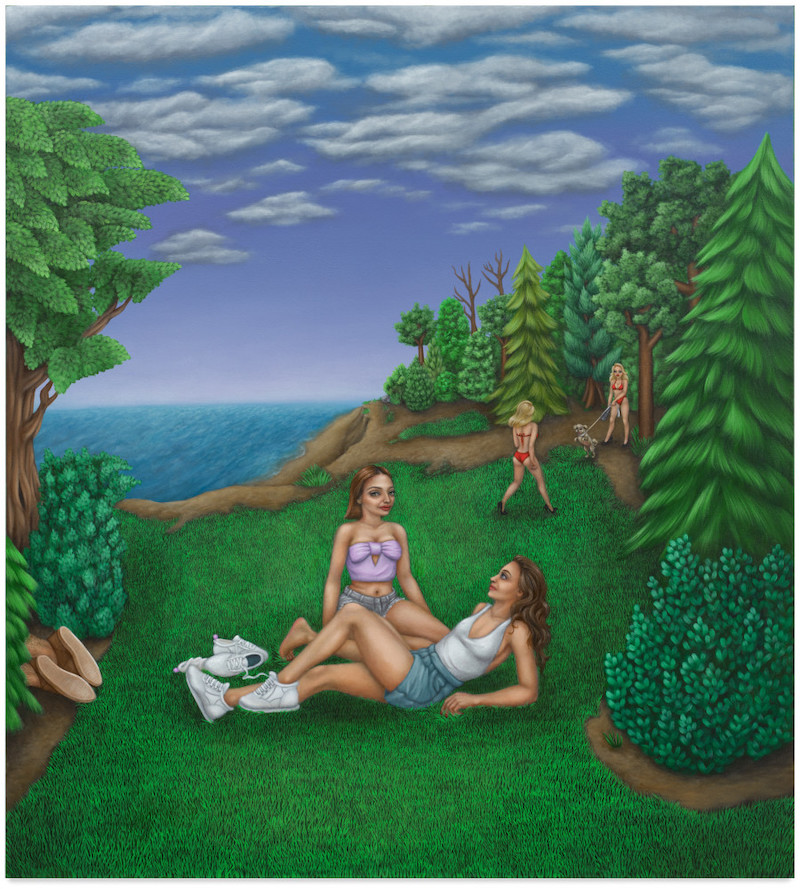

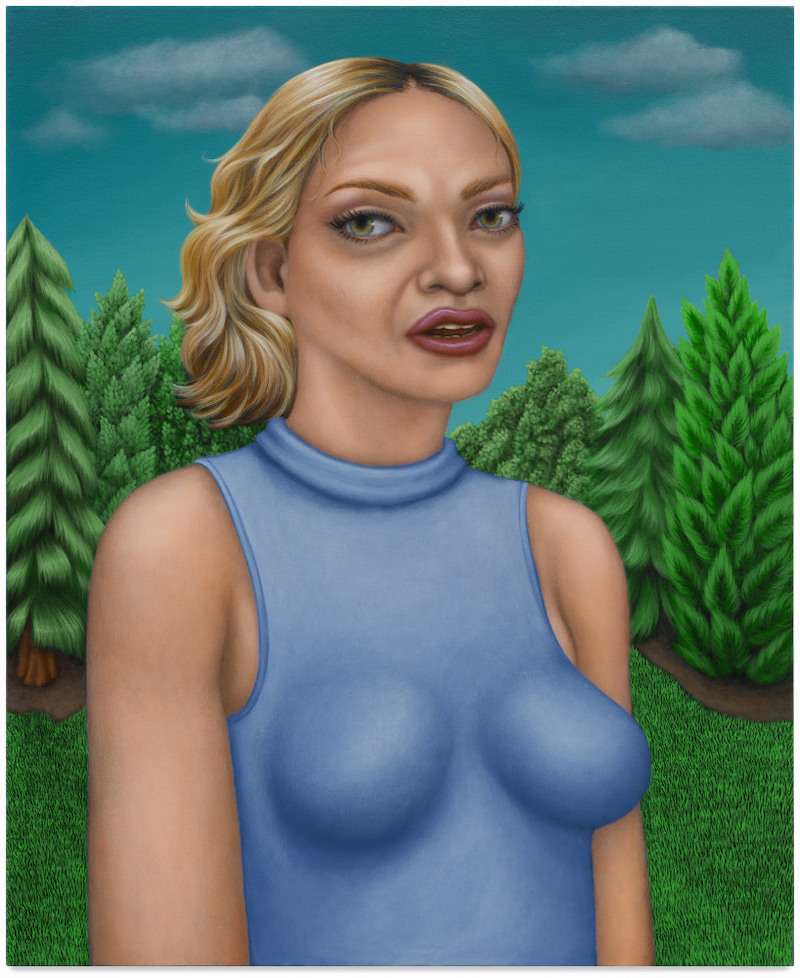

In Under New Management, Stacy Leigh creates an alternative universe where women are in the midst of revolt and ready to take over control. The artist’s interest in world-building began in her childhood when collecting dolls became an obsession and an escape from life’s stressors. Through painting, Leigh continues to imagine a rich fantastical world, where centuries of patriarchy begin to crumble. In this new body of work, Leigh executes loud and bold acrylic canvases featuring empowered women, all of whom are figments of her imagination. The bright, bucolic suburban landscapes stand in contrast with a subject matter that is at times dark and unsettling. In Leigh’s woman-driven world, men are dropping dead like flies: the male presence is made known only through pairs of legs at the edges of her compositions. The men, positioned face down on the floor, can be found on busy New York City sidewalks, behind shrubs in a lush forest, or smashed under a red Pontiac Firebird. Red bikini-clad femme bots descend to Earth and approach men as a litmus test, turning them into dogs as a punishment for misbehaving. Leigh’s ambiguous subject matter hints at violence without explicitly showing it.

Under New Management tells both a personal and political story. The series provides Leigh with a vehicle to express frustrations over her ongoing legal battle against the all-male board of her condominium building. A former stockbroker, Leigh has experienced her fair share of misogyny as a woman working in Wall Street’s all-boys club. On the other hand, Under New Management is a commentary on institutionally sanctioned barriers placed on women—rescinding reproductive rights, normalizing a gender wage gap, and perpetuating harassment and violence. Despite being rooted in social critique, Leigh’s paintings don’t take themselves too seriously; they are coated with humor from their titles, Ladies of Leisure Don’t Always do Lunch, to their hidden messages, such as a doormat that spells out “Nope,” a canned drink called “Big D Energy,” or a storefront with a “Revolt” sign. In this nearly separatist society, Leigh’s women are revisionists choosing to reject pain and live to their full potential, without men obstructing their way. Even if it means having to get rid of them.

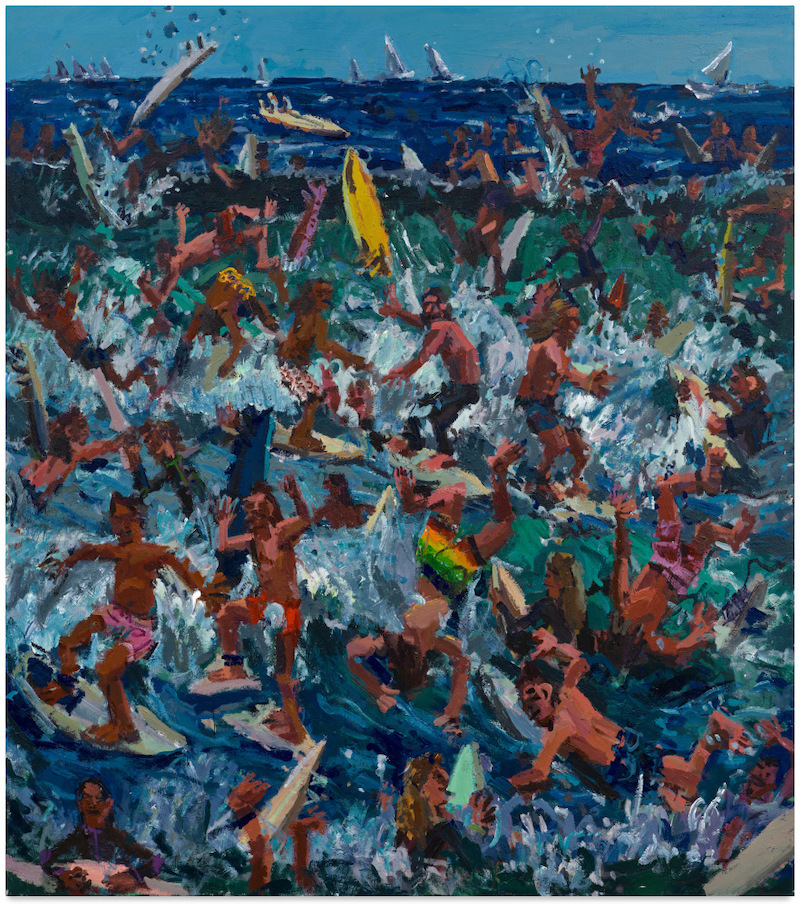

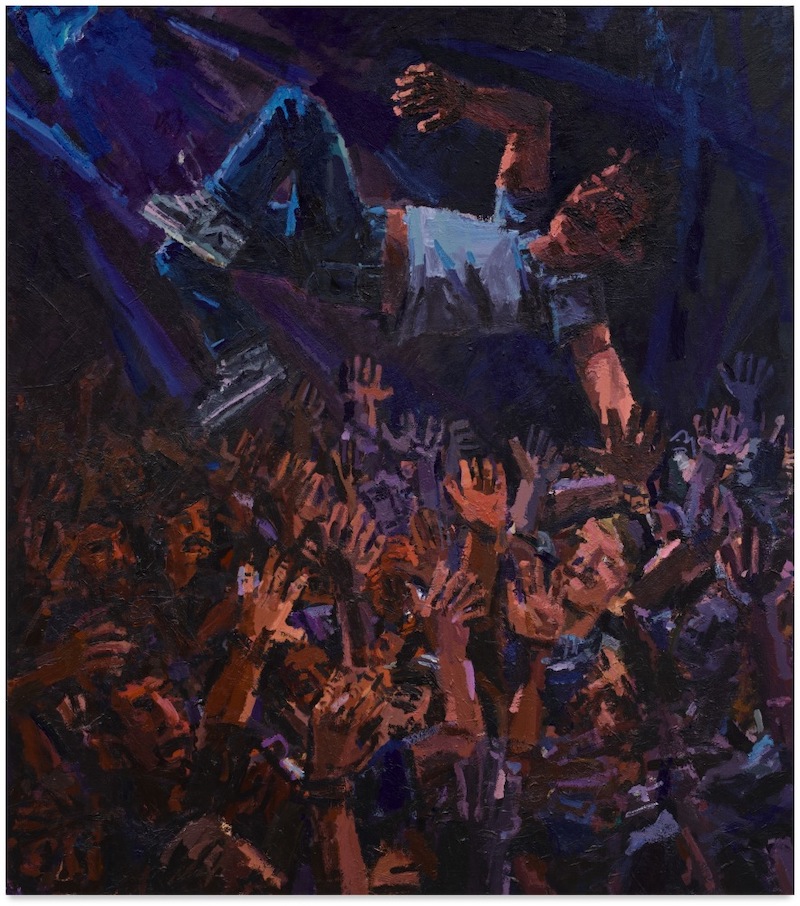

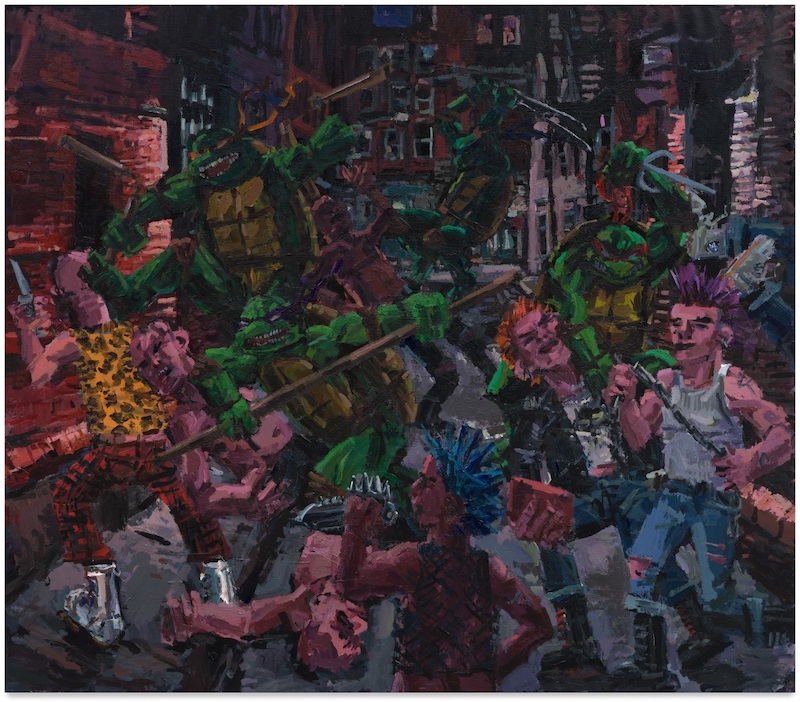

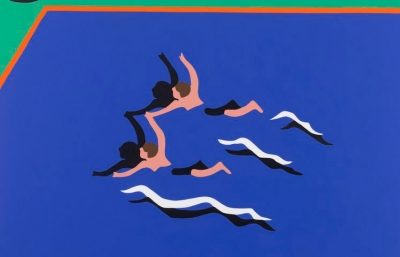

In Rabble Rouser, the content of Todd Bienvenu’s textured acrylic canvases is autobiographical, providing an energetic look into his interests in surfing, skating, punk music, and his role as a husband and soon-to-be father. In densely layered paintings, Bienvenu packs an unbelievably large group of surfers into one space to catch a wave. The heavy layers leave an imprint of the artist, something he finds refreshing in a digital age. In one instance, a sea of hands guides a crowd surfer at a concert, while in another painting, spectators at a football game rush the field. The crowds are so large that faces begin to blur and blend into one another, becoming abstracted. The artist’s deep interest in light gives the paintings a cinematic quality and directs our eye to a focal point. Perhaps the most cinematic and imaginative of all is TMNT, where we find a group of punks, armed with poles and knives, fighting the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in a dark alley. Here, the artist is harkening back to the fictional characters of his own childhood—a self-reflexive exercise for the expectant dad. Who is the rabble-rouser in this body of work? The musician on stage, the leader of the gang, or the artist himself?

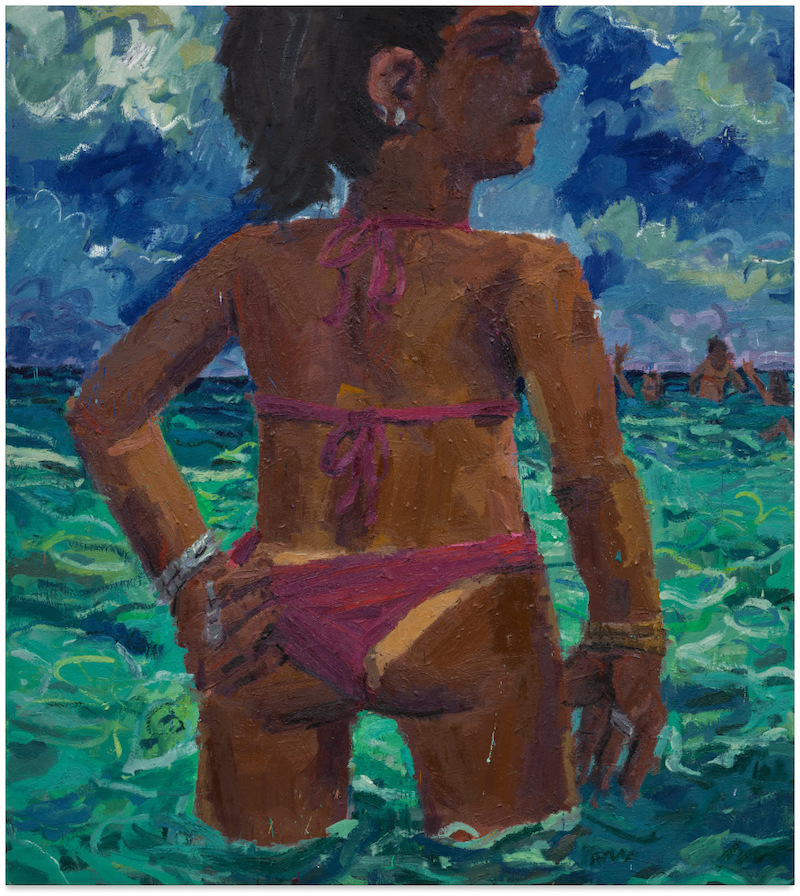

Bienvenu’s wife makes several appearances in this series; the artist chooses to create unconventional portraits, where her essence is captured more than her likeness. Rather than be sucked into a large crowd, she is presented to us as a solitary figure, whether she is on a roof in Brooklyn taking in the Manhattan skyline at night or in the ocean looking over her shoulder. Bienvenu always inserts his sense of humor into the works; in Big Wedgie, his wife is caught in the act of picking at her bikini bottom, revealing an impressive tan line. Perhaps these snapshot portraits intentionally contrast with the chaotic, action-filled canvases to show that for Bienvenu, his wife is a source of solace, stillness, and calm. The artist is admittedly self-reflexive and self-conscious, consistently pondering what it means to be a heterosexual man, a partner, and a father. He also wonders where he fits within the lineage of male artists, specifically the Abstract Expressionists of 1950s New York, whom he tries to move away from both formally and personally. Bienvenu makes a conscious effort to counter these artists’ reputations as alcoholics and abusers by leading with compassion. Both self-deprecating and sensitive, he captures an alternative male energy, one that steers clear of toxic masculinity. —Tina Barouti