It is quite a talent of mine to come across a gallery exhibition mere days before it is set to close. Of course, that is the dichotomy of their installations. The rush to experience the work before it bids adieu is a part of the allure, and I usually find myself setting up for the farewell party. I try to savor the moment (and the art of course), accept my luck for what it is, and move on. But when I was walking through Paris the other day and came across the work of Louis Barbe, well… that was something I just could not do.

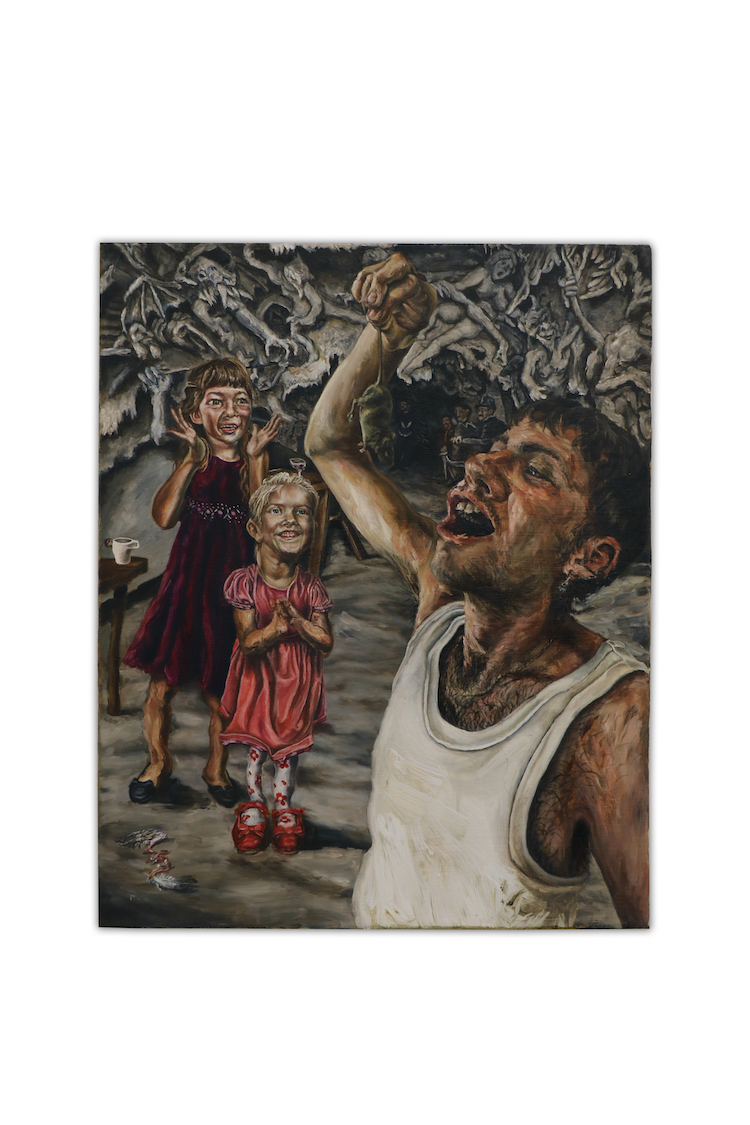

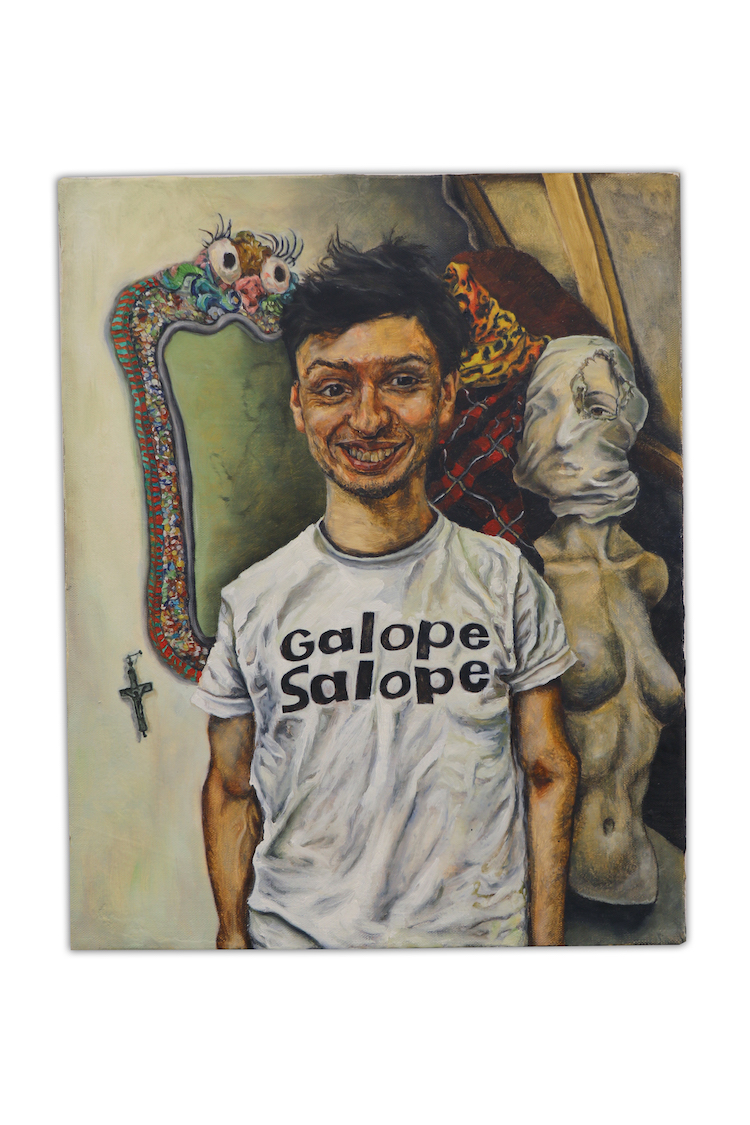

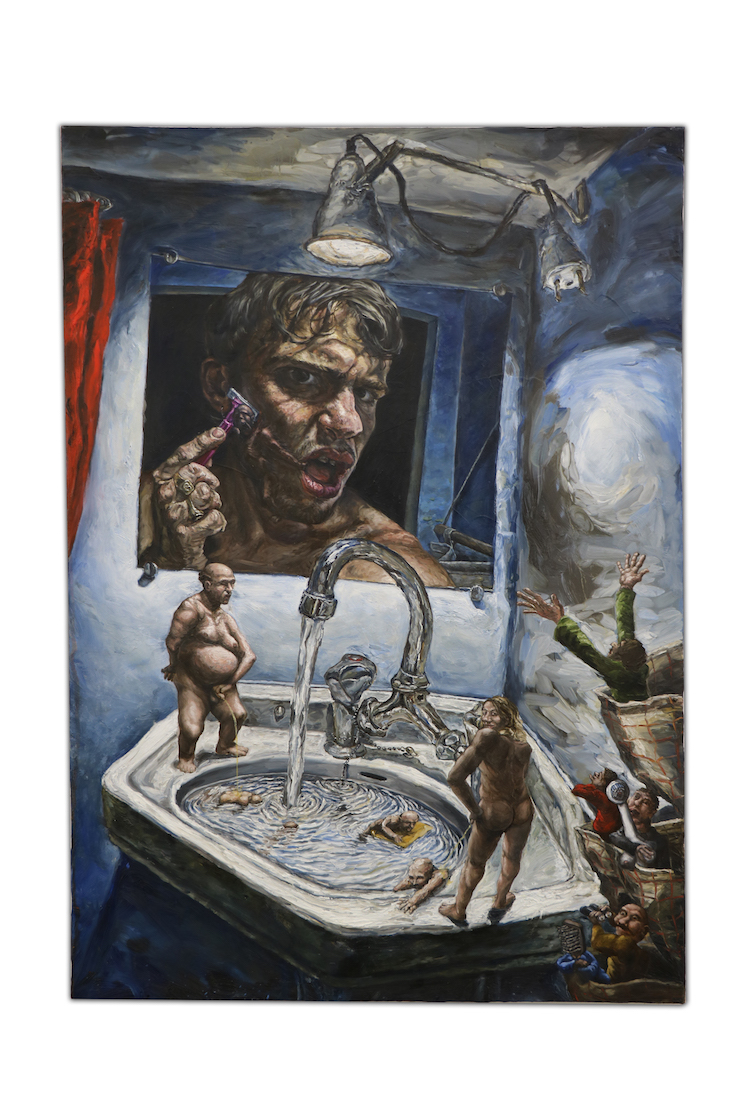

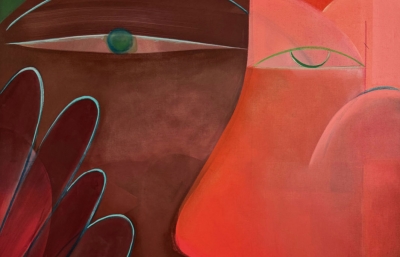

Barbe just closed his solo exhibition La Nuit N’est Pas Finie (The Night Is Not Over) at the Galerie Sabine Bayasli, representing the last year of his work. Walking past the gallery window, there was a piece that stopped me in my tracks in which Barbe portrays himself about to indulge in the delicacy of a mouse, called Saphir Pasta. For about a week or so Barbe, who is a mere 21 and is starting his third year at Les Beaux-Arts de Paris, has humored me by responding to my various emails and questions around his work. In reply to my desire to, understandably, learn the story behind this painting he shared, “Usually my paintings start around multiple ideas, stories, and personal matters that I connect to. For Saphir Pasta it was linked with a really strong smell in my atelier at school which I was convinced came from a dead mouse. No one believed me until I found one dead in some green paint.”

The background of the painting is a cacophony of the peculiar. Two pretty young girls in dresses watch on and clap their hands in delight; monstrous demons swirl in the sky seemingly encouraging the momentous debauchery; a group of strong men, possibly exhausted soldiers wearily keep their distance–a battle they couldn’t seem more disinterested in engaging. “For the swirling demons in the background it came from Le Cabaret de L’enfer,” shared Barbe. “It was a place in Montmartre (Paris) in the early 1900s and the barmen would serve the drinks from a giant cauldron. It was a place known for being frequented by surrealist artists, but there are also archives of soldiers hanging out there.”

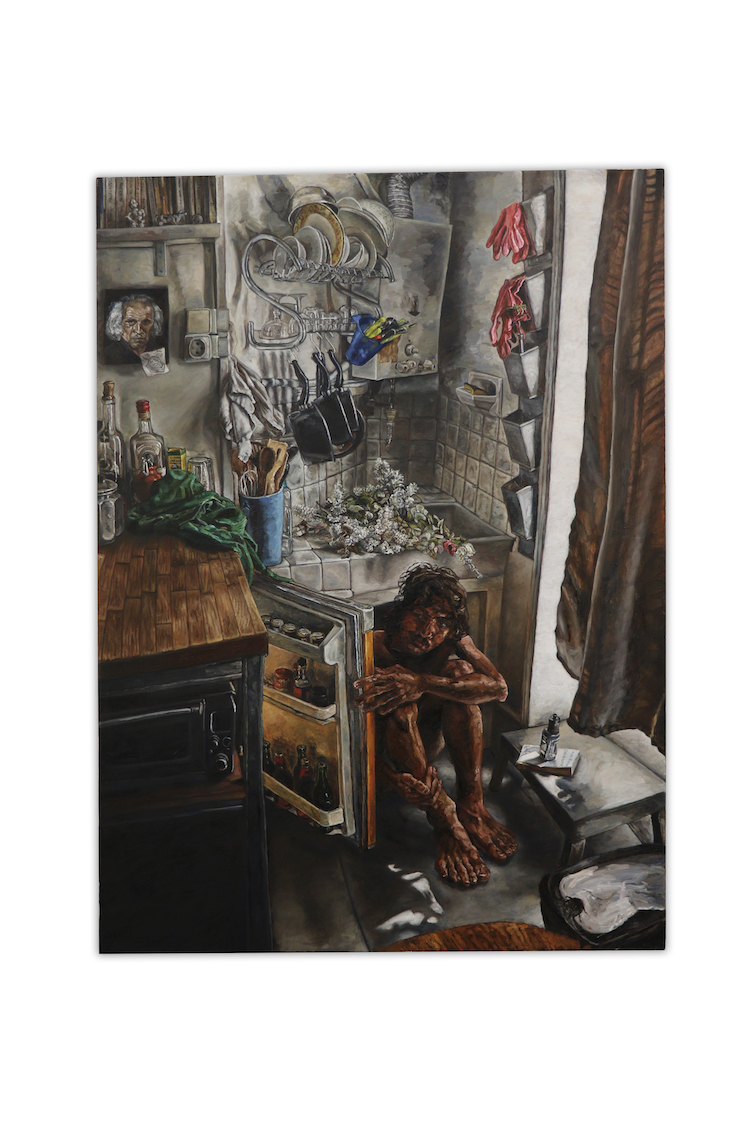

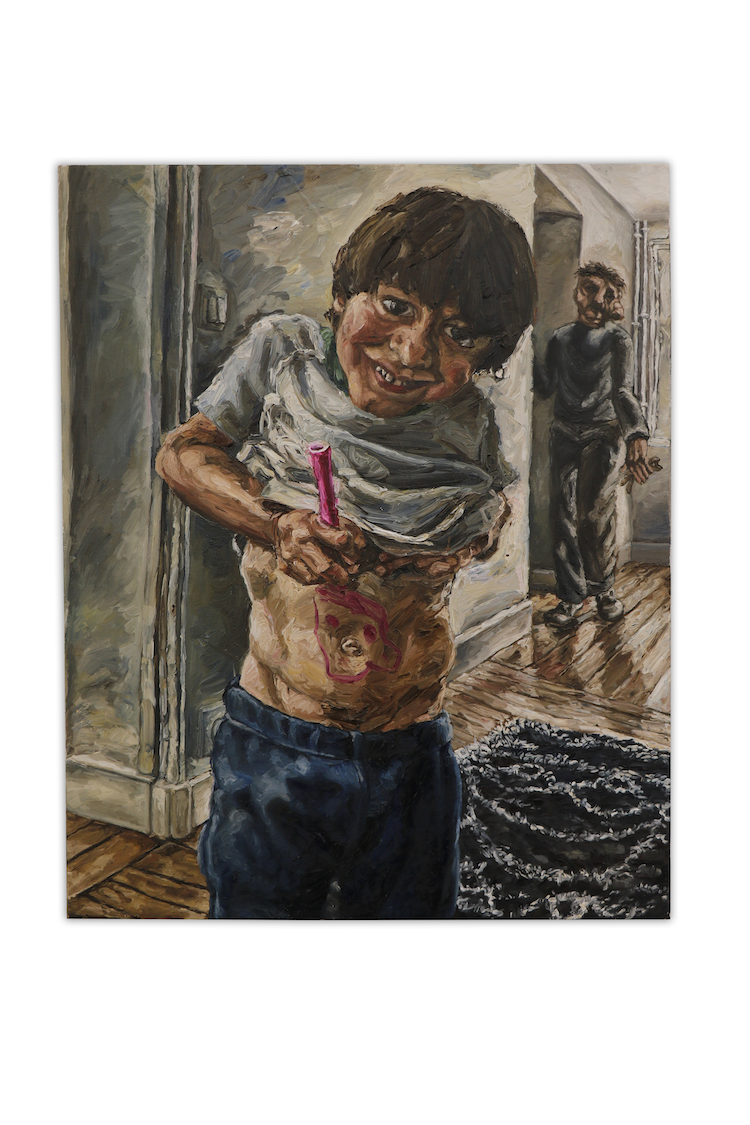

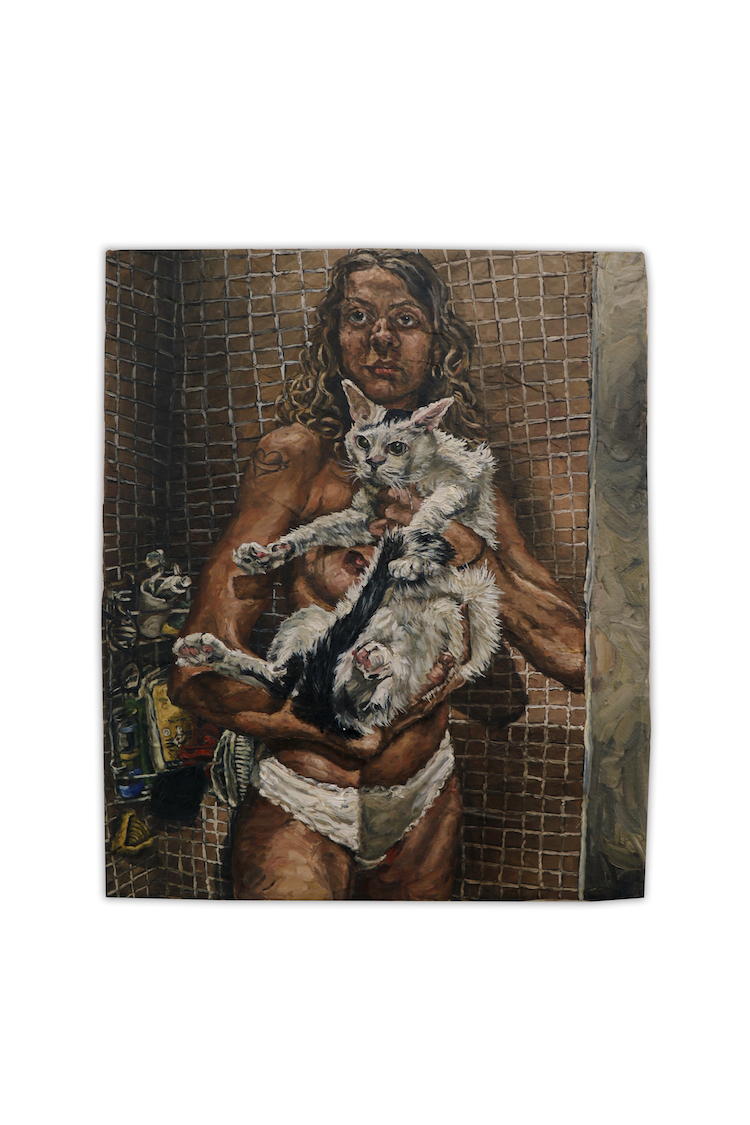

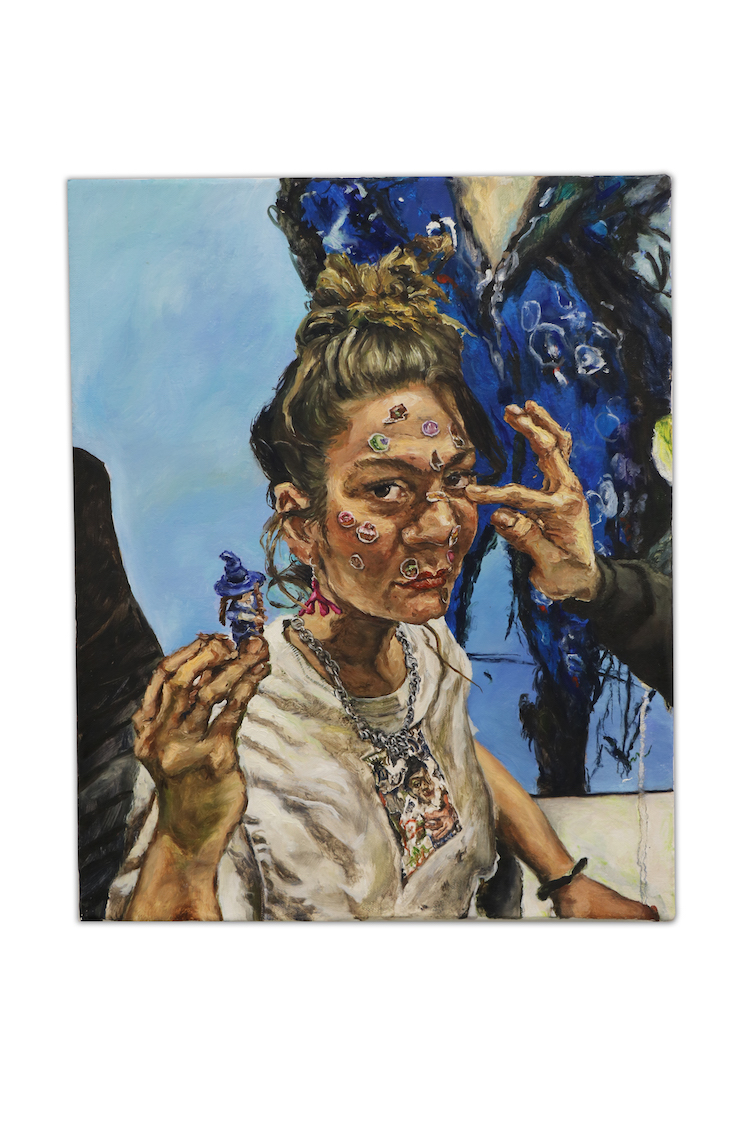

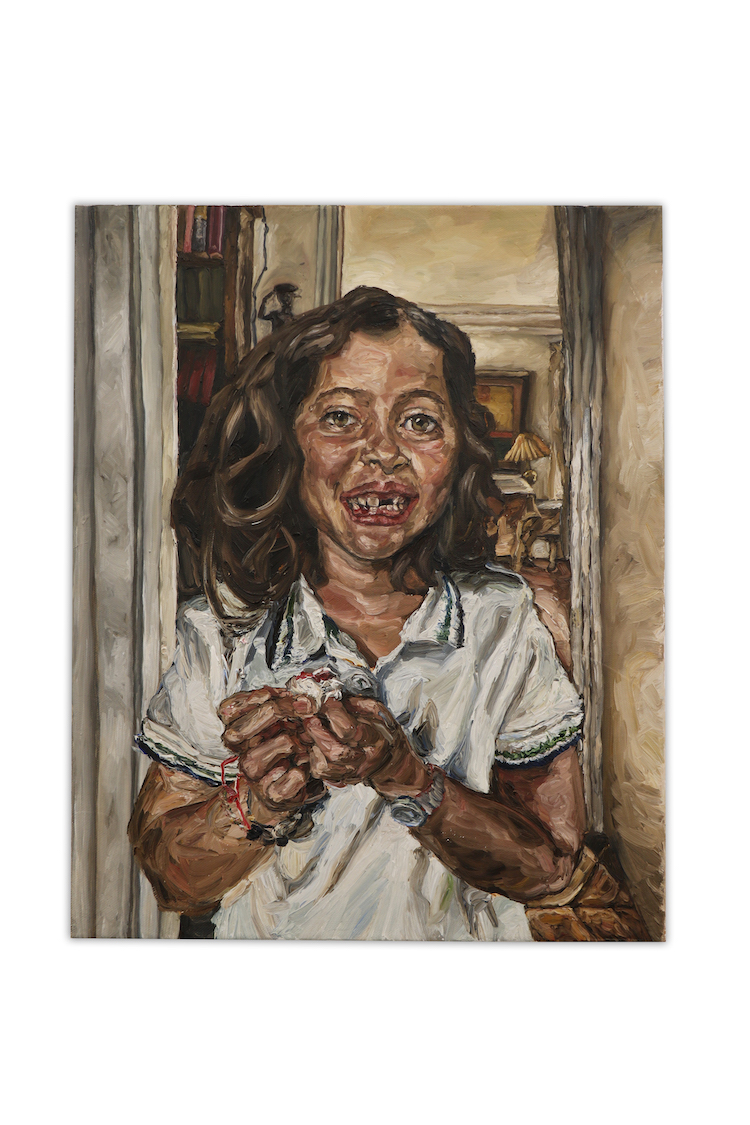

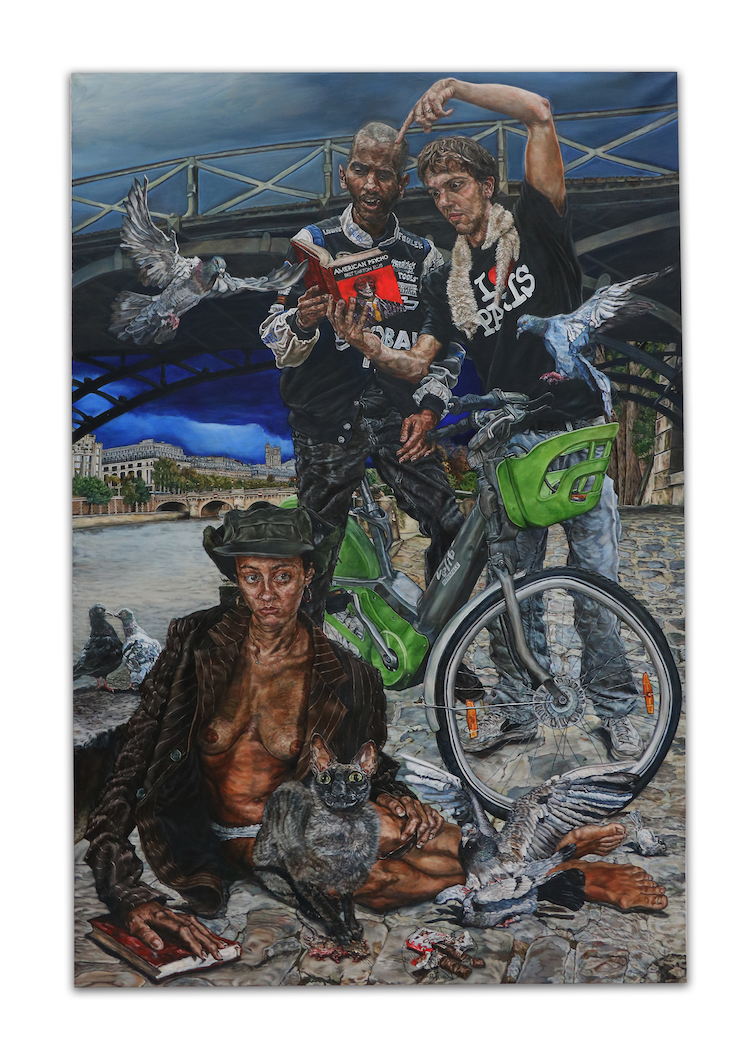

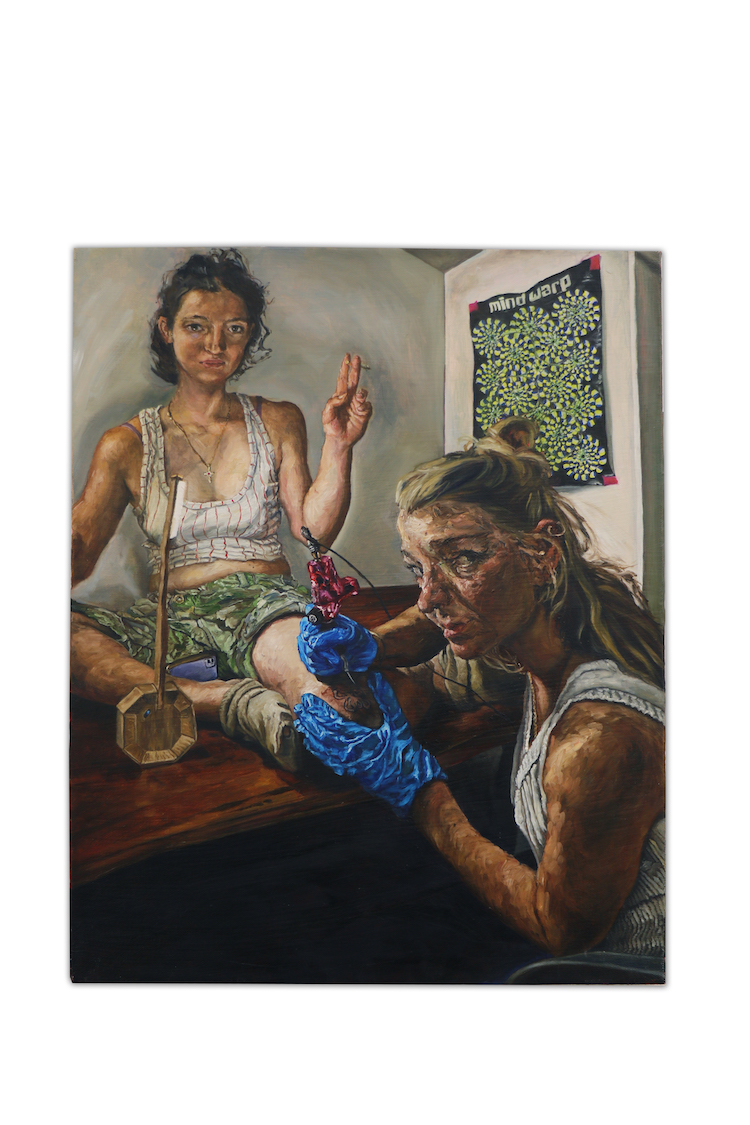

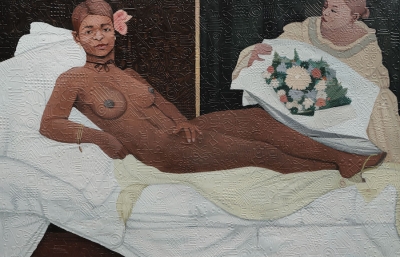

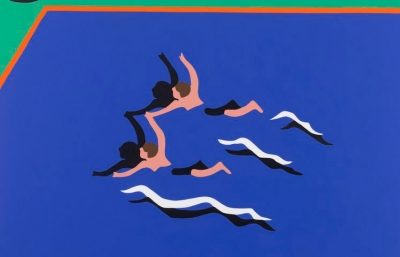

Each of Barbe’s paintings feel like short stories exploring the oddness of our accepted realities, (and I had to stop myself from questioning him about every single one.) In a separate work a couple cuddles soundly on a twin sized mattress while a pioneer trope of cockroaches sing songs around the campfire beneath them. A teenage girl stands in a beautiful field looking at a half-nude woman on her phone, while a cow breaks the fourth wall, staring at you in a moment of shared disbelief. Three members of a family sit around a table splitting one egg in thirds for their dinner, while a fourth small child opens wide in preparation for a spider to serve as his. “My work comes mostly from something that has been stewing in my mind for many weeks. This little impulse is fed from stories I hear or read, until I’m able to find the impact of the images, which is what you see on the canvas.”

What I love most about Barbe’s work was his obvious ability to trust himself. To stew on life's mundanity, follow an idea down to an extreme absurdity, and paint it with all the seriousness that it deserves. “Sometimes I feel like not everyone understands the ambiguity in my humor, which is a big part of my practice.” —Shaquille Heath