Karma presents My Journey Was Long So That Yours Could Be Shorter, an exhibition of new paintings by Nathaniel Oliver, on view through March 2 at 188 East 2nd Street, New York.

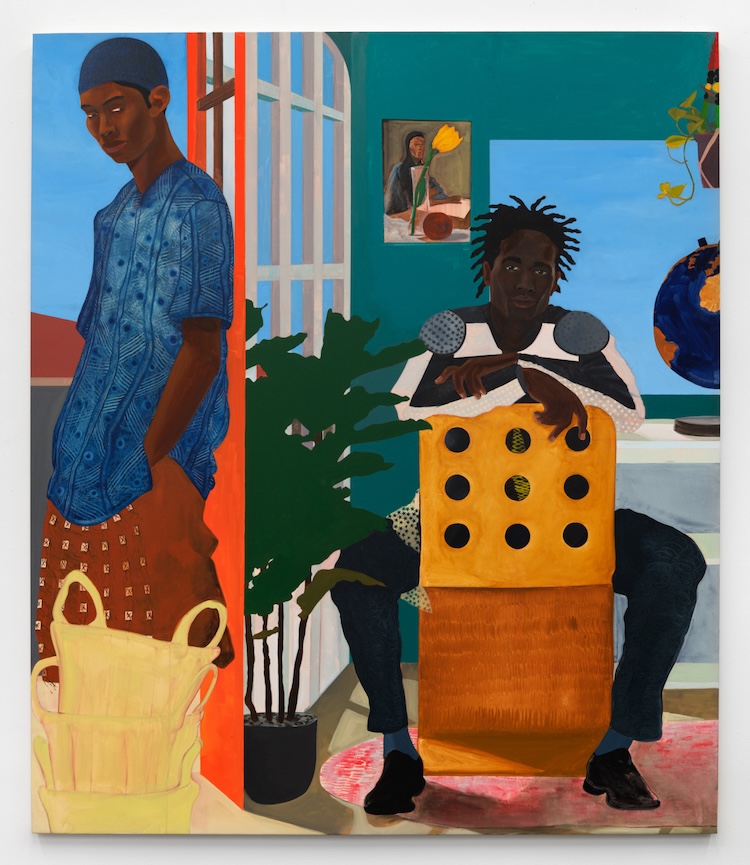

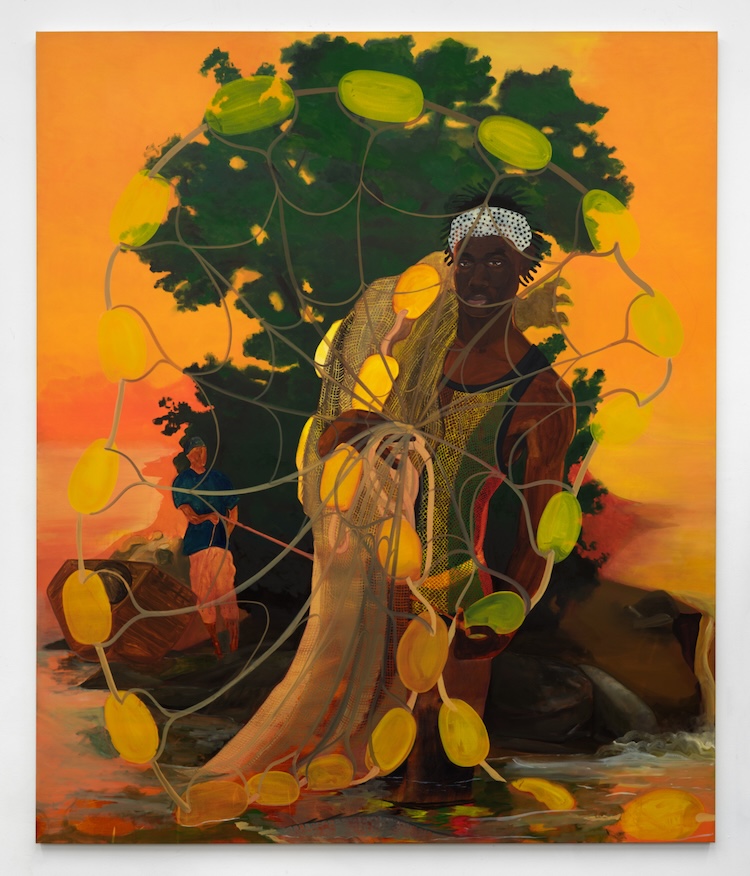

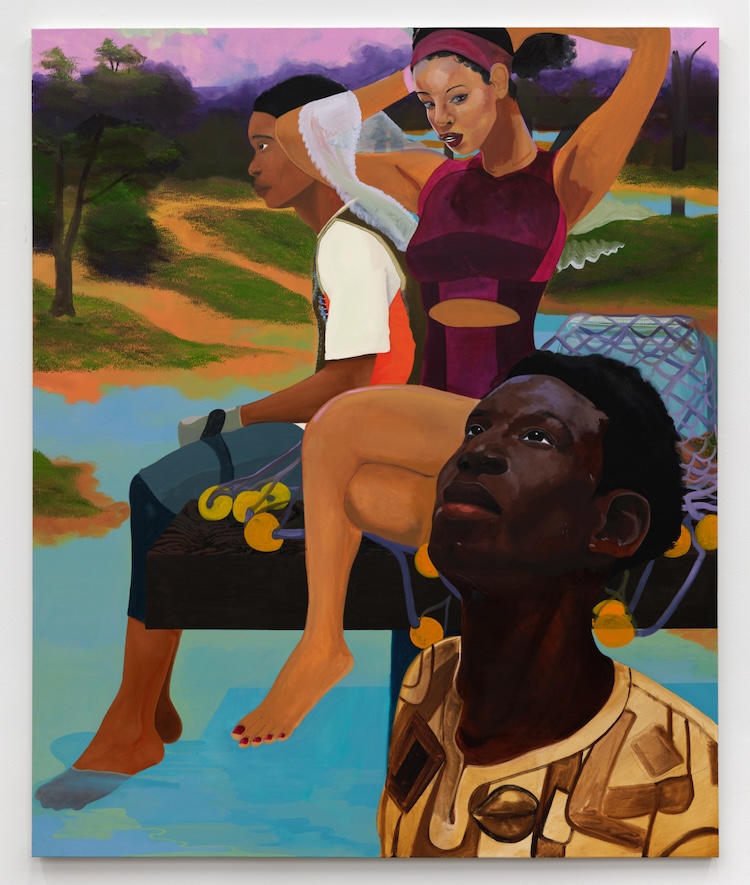

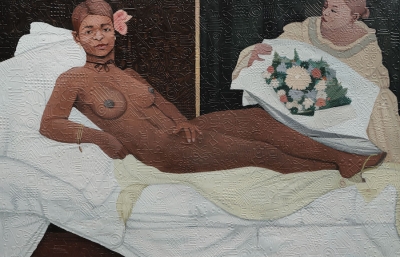

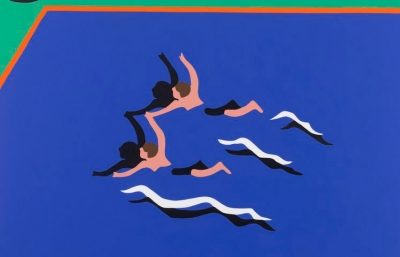

Nathaniel Oliver’s narrative paintings build from our material world, extending into the realm of fantasy. The artist first develops his compositions by sketching from imagination, later adding specific images and objects from all corners of art history and his own life. Like a printmaker, Oliver constructs his paintings from discrete layers of uninterrupted color before adorning them with pattern and texture. His strategy is also one of accumulation—he conflates disparate representational styles, cutting and pasting from an encyclopedia of references, many of which belong to his personal canon of Black painting. Visual citations of West African culture appear—ranging from contemporary Malian textiles, to gris-gris charms from Sierra Leone, to Nigerian ceremonial masks—as do flora and fauna native to the Caribbean, where Oliver’s father was born. His works also foreground oceanic motifs, simultaneously evoking the centrality of the Atlantic to the artist’s upbringing near a wharf in Washington, DC, Homeric epic poetry, and the enduring legacies of the Middle Passage.

My Journey Was Long So That Yours Could Be Shorter points to the personal and societal struggles borne by generations in order to clear new paths for those who come after them. The world in which the exhibition’s paintings take place is parallel to our own, and contains some of its elements, yet remains outside of our timeline. The likenesses of its characters are based on friends and family members whom the artist thinks might suit each role, further confounding fact and fiction. Figures recur across multiple canvases, as if they walked out of one and stumbled into another.

In the dock scene At What Cost, Do I Stay or Go, a silhouetted figure tosses a roll of fairground tickets through the opening of a slightly parted curtain. The drapes, their patterns based on textiles from Mali, are suspended in space, untethered to any architecture of this world. A subway turnstile and a man holding a rooster in one hand and a knife in the other occupy the foreground. Beside them is a marble figure, its body bent deeply backwards, arms in an expressive position modeled on those made by marching band members. At What Cost, Do I Stay or Go is an allegory for the sacrifices necessary to pass from the corporeal world into the spiritual one. Who is granted access to transcendence, and who is denied?

In Would You Believe Me If I Showed You, a regal woman in a canary-yellow gown sits at a desk in front of a large open window that looks out on a terracotta roof top similar to those Oliver encountered while traveling in Lisbon. The artist adapted her pose—seated, in profile, drawing a sea monster on a sketch board—from a Baroque woodcut of the Greek prophetess Sibyl. A plank mask from the Bwa people of Burkina Faso and a painting of a Black knight drawn from a Renaissance altarpiece adorn the room’s walls. Her earrings are cowrie shells, a mollusk husk symbolizing prosperity that was used as currency in Africa for hundreds of years. Like Oliver, the female artist in Would You Believe Me If I Showed You is both a product of numerous cultures and the creator of a world all their own.