François Ghebaly in Los Angeles curently is showing a new series of paintings, Moonlight, by UK-born, Berlin-based painter Tom Anholt.

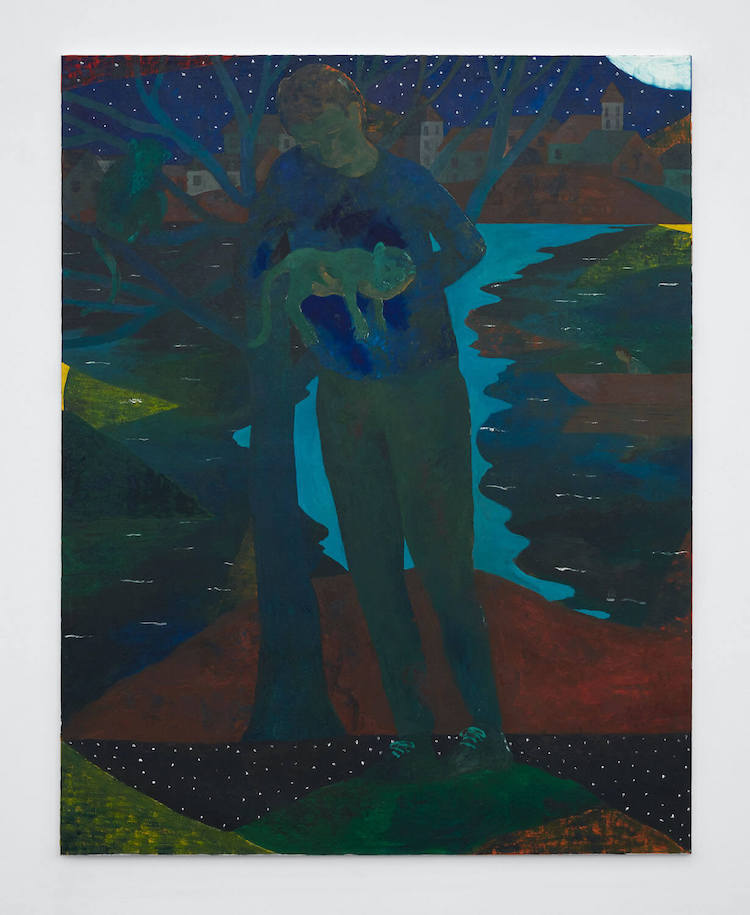

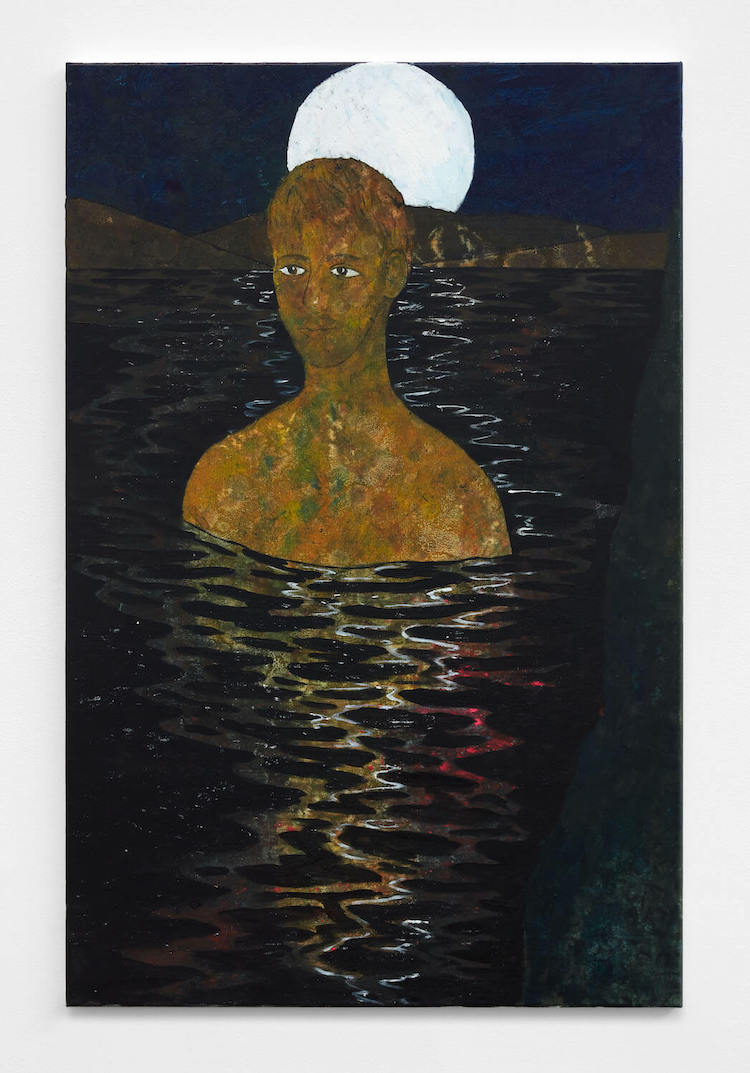

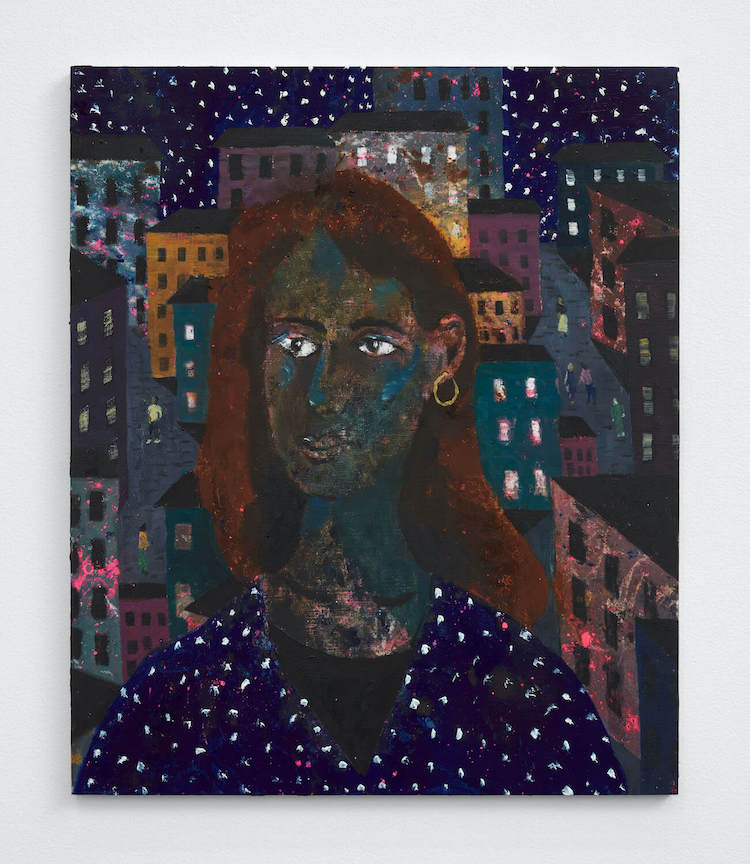

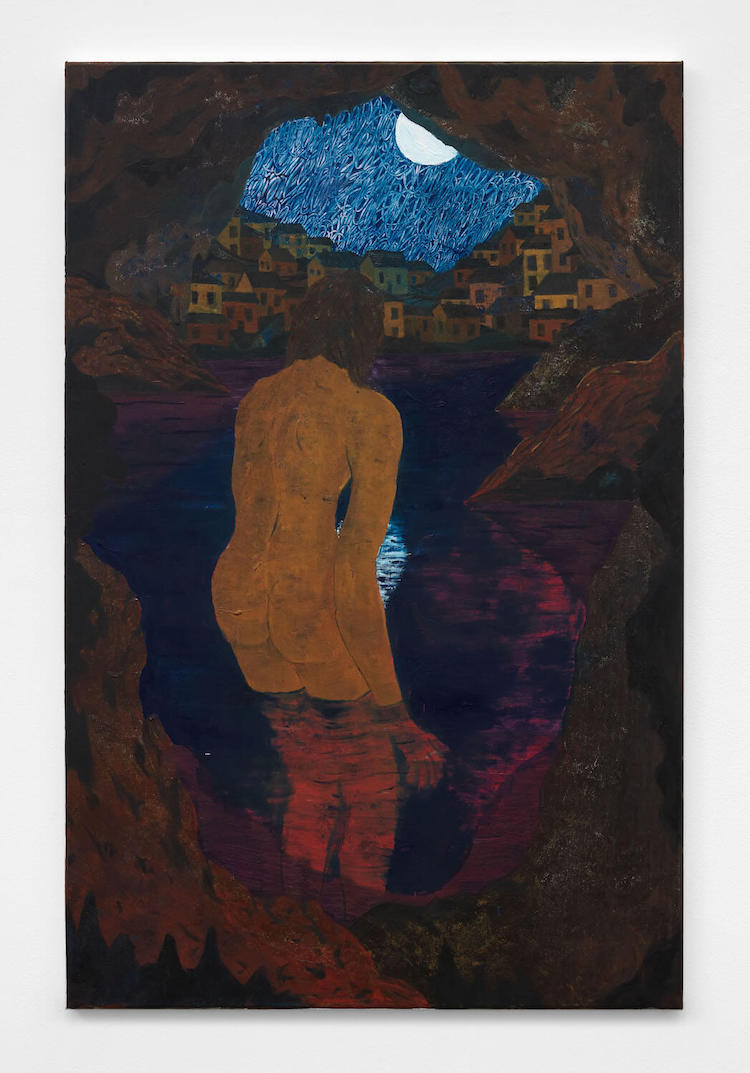

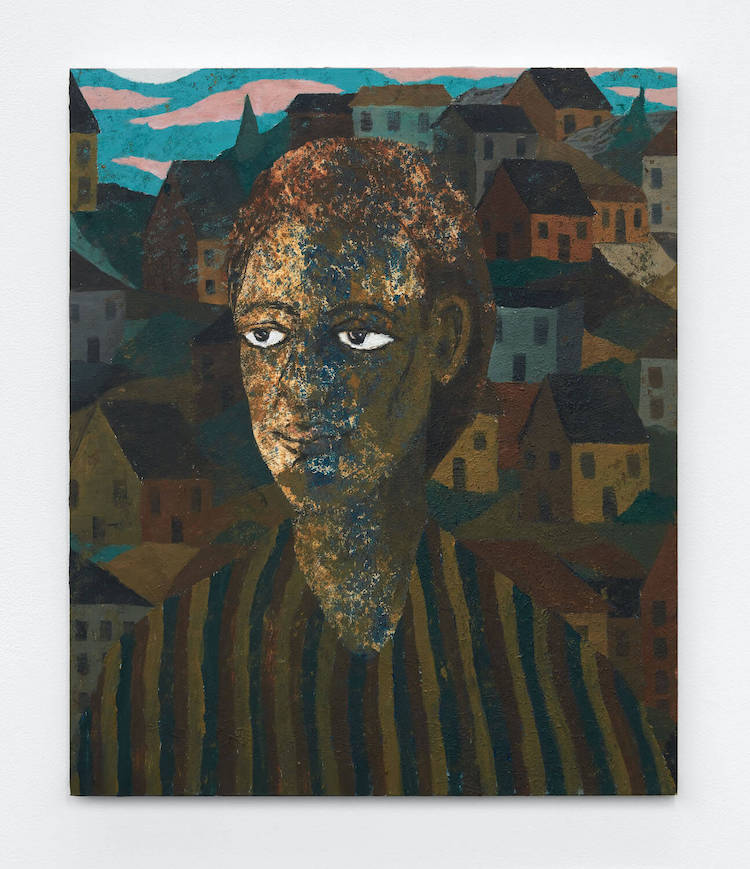

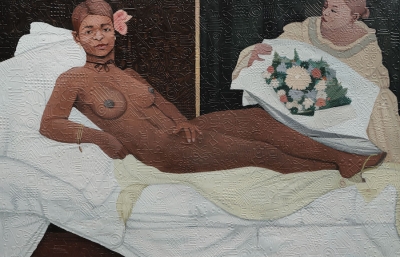

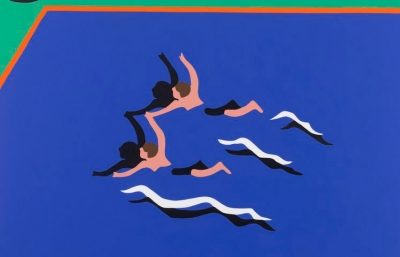

All light is moonlight, it seems, in Tom Anholt’s anthology of poetic ruminations across eleven interwoven paintings. Muted fallow hues are starred with glimmers of brightness—yellow, cobalt, and verdant green—that catch and cradle the lone moonrays in each shimmering landscape. In works like Choices (2021) and The Hunt (2021), this cast of moonlight illuminates his figures to a dazzling radiance, upwelling the quiet humanism wherein each of his paintings is invariably steeped.

The omnipresent nighttime in Anholt’s work is, on the one hand, a clear invocation of the prescience and acuity that belongs only to night. In Young Love (2021) and Care for me and I’ll care for you (2021), the twilight haze and pitch-dark glow achieve a similar retention of feeling that deepens and variegates each figure’s emotional labor. For Anholt, though, the recurrent moonlight suggests something of a devotional as well. The symbolic underpinnings of the motif move beyond a simple contrast between ‘moonlight’ and ‘daylight’ or ‘artificial light,’ to attend the artist’s own exercise of repetition and commitment—“you do something, and you stand by it, because from those constraints comes creation. And these became moonlight paintings.”

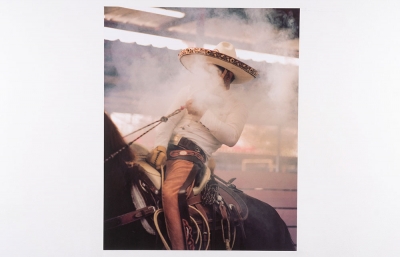

In this sense, Anholt’s work is concerned with the very practice of the painter: “you’re always painting portraits of what it means to be a painter”—that is to say, the isolating postures that the painter occupies to bear witness and reflect in their work. Figures are conspicuously solitary in his paintings, either entirely alone on their respective canvases, or divided from their peers and civilization by time, distance, and gesture. In The Raft (2021), the lone sailor’s figure merges with the glowing green waters in the foreground and extends to the landscape and nighttime sky, visually excluded from the bright blues, yellows, and earthen tones of the houses along the shore. The Troglodyte (2021), the bather, and the horseback sojourner, too, are made pilgrims by the piety of their unwitnessed labor, both in the context of their individual scenes and in Anholt’s underlying pedagogy of asceticism. Thus, the ubiquity of moonlight becomes, by extension, the ubiquity of the self portrait, each painted element reflecting the volition of the lone artist’s hand that carved its very being, and imbued, unfailingly, with Anholt’s own poetics of good faith.