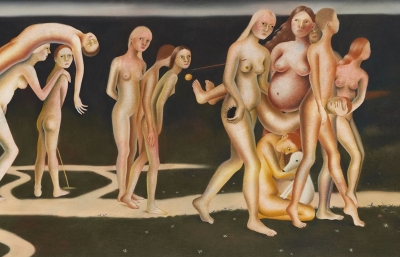

One of the most-talked abour shows of the season has to be Lisa Brice's LIVES and WORKS at Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris. In her latest body of work, Lisa Brice continues to challenge traditional representations of women in art history. Inheriting from and renewing the genre of the nude as painted by male artists, she transposes familiar scenes in an act of re-authorship that proposes an alternative to the power dynamics inherent in such images.

The characters and settings that appear in Brice's paintings are built from diverse images collected from personal photographs, various media and, above all, art history, which provides a rich seam of inspiration for the artist. "All painting is a lineage – it's all a conversation with what has come before," she says. Drawing specifically on paintings made in Paris from the mid to late 19th to early 20th centuries, in the works on view, Brice is responding to the work of painters historically active in the French capital.

"I like to think that my paintings are the antithesis of misrepresentation – the reclamation of the canvas by all the models, painters, wives, mistresses and performers," Brice says. "The spaces I depict are dream-like in the sense that they are fictional, but very much based on reality and lived, sensorial experience."

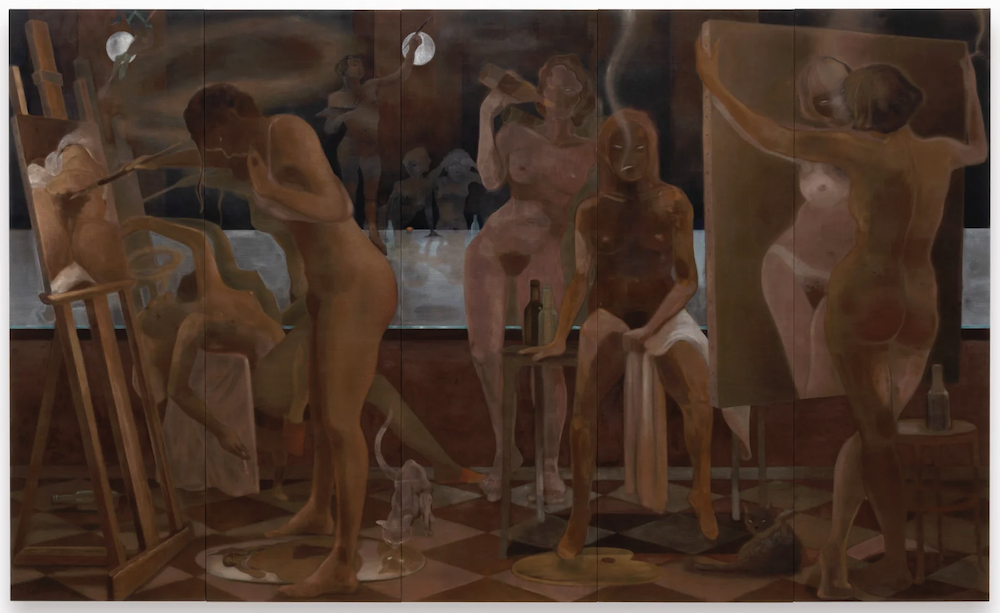

Brice echoes and reimagines art historical figures and scenes while reclaiming them from a male gaze that effectively disempowers women as passive objects of desire and refracting them through ideas of self-representation and empowerment. The woman on the far left in this work paints her own anatomy in a subversion of Gustave Courbet’s L’origine du monde (1866; Musée d'Orsay, Paris), which depicts a nude female model’s lower half. By painting herself, the woman in Brice’s work is liberated from the restrictive role of model to become the author of her own likeness.

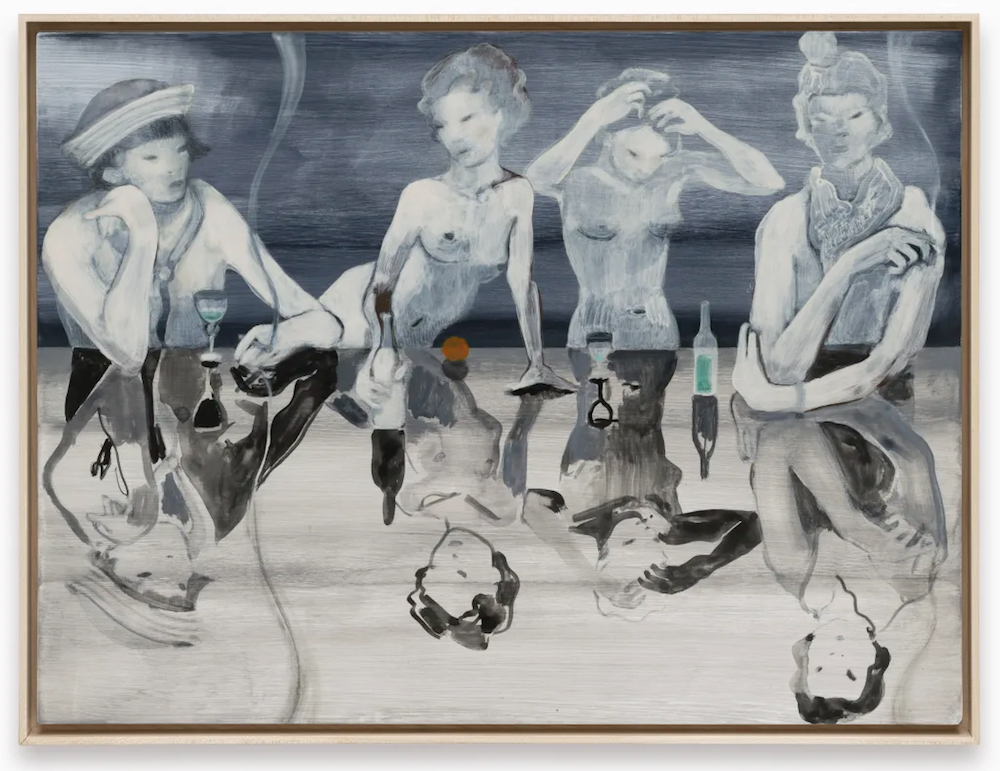

Brice grapples not only with the questions of gender but also of race generated by the paintings she references. In one of the works on view, she returns to Félix Vallotton’s charged The White and the Black (La Blanche et la Noire, 1913; Kunstmuseum Bern), itself made in response to Édouard Manet’s controversial Olympia (1863; Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

The title of the exhibition, LIVES and WORKS, is a play on words. Both interchangeable as verb and noun, the two terms recall the opening words of an artist’s biography while simultaneously signifying the duality of the existence of the female artists/models, such as Suzanne Valadon, whose essence underpins the works on view.

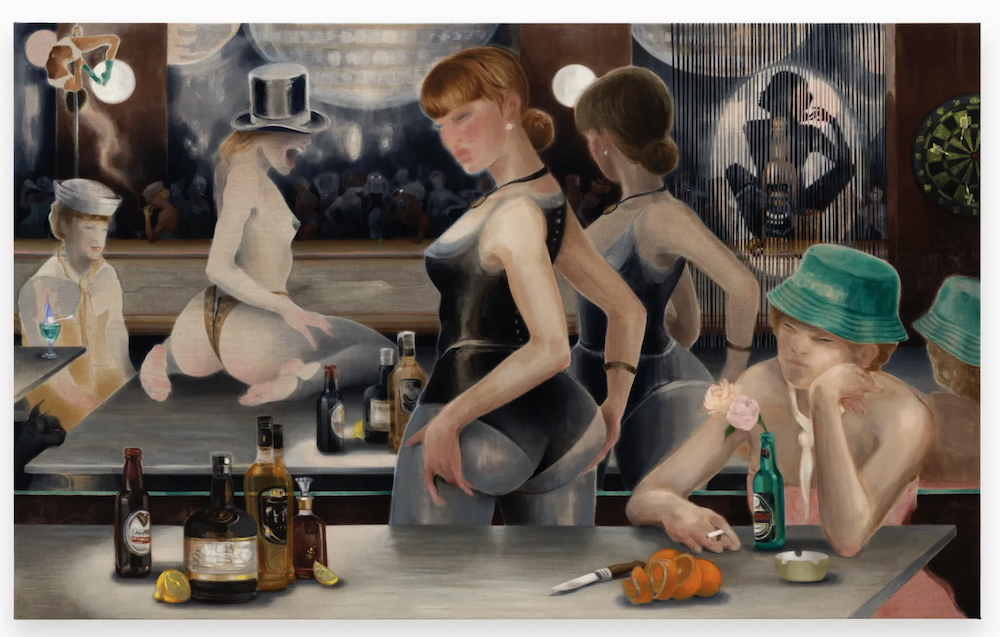

The bar is a recurring setting in Brice’s work. This space, which was typically male-dominated in fin-de-siècle Paris, is transformed by Brice into a safe haven for women. The palette of this work, as well as its composition – split horizontally by the line of the bar – and the prominence of the wine glass, recall Picasso’s Pierreuses au bar (1902; Hiroshima Museum of Art). In Brice’s bars, always devoid of the expected male presence, women sit at ease, smoking and drinking freely.

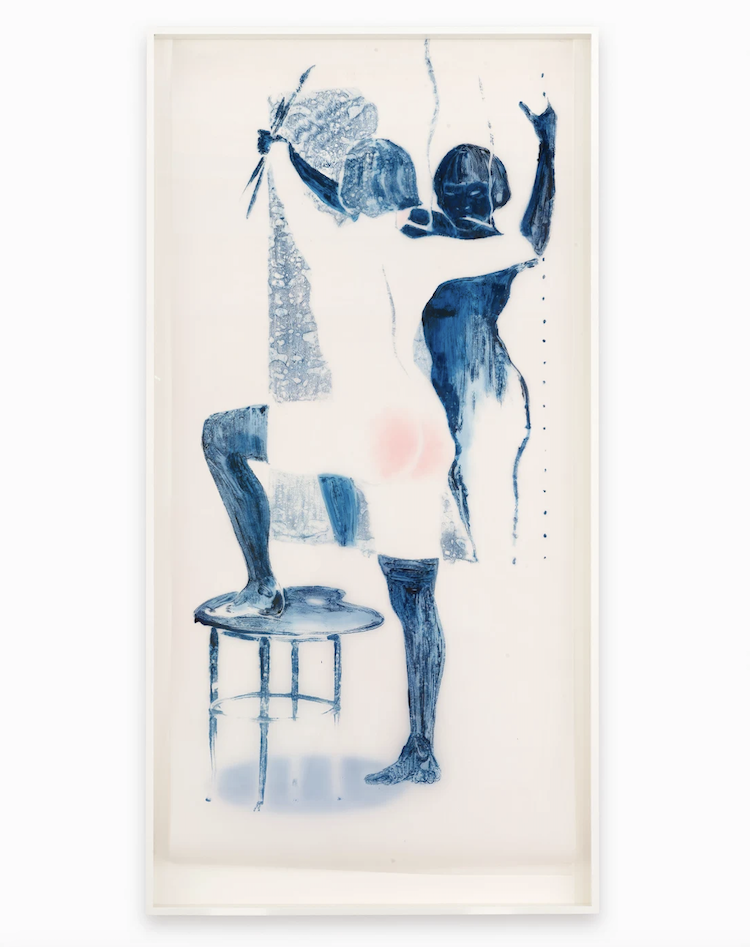

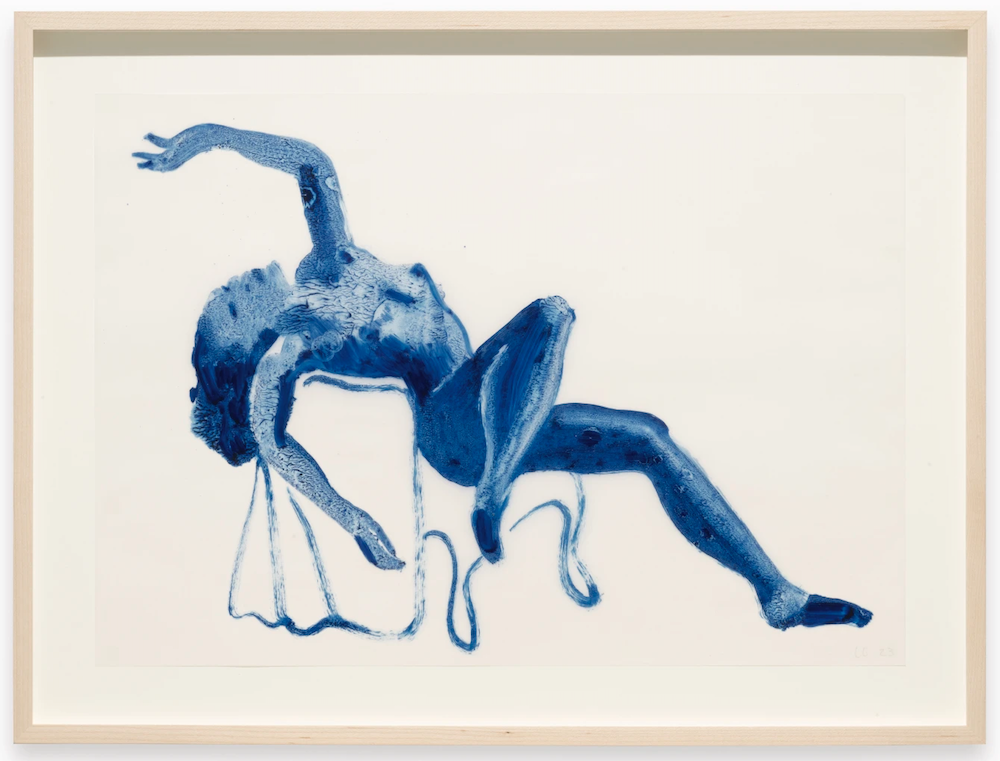

The blue drawings are a way for Brice to process source images into her own hand and visual language. This practice of drawing enables her to identify figures and poses that may become part of larger compositions: an audition of sorts. These preparatory drawings have evolved into works in their own right, and are often exhibited together, placed in conversation with one another.

Pulling her subjects out of history and bringing them together, in LIVES and WORKS, Brice sets up an intergenerational conversation: "rescu[ing] previously isolated figures of women from the confines of a renowned painting and giv[ing] them a new existence, among a fresh grouping of other women – a liberation of sorts," as Brice said in a 2021 interview with Tate curator Aïcha Mehrez. In studios or bars, emerging defiantly from wisps of cigarette smoke and low lighting, whether confronting viewers with a direct stare or seemingly unaware of their presence, the artist’s subjects stand as empowered figures driven by their own desires, rather than those of the spectator. Brice is once again, as Yasmijn Jarram, curator of Brice’s 2020–21 exhibition at Kunstmuseum Den Haag, wrote, not "serving the viewer’s gaze, but rather directing it."