Perrotin Seoul is pleased to present Please Throw Me Back In The Ocean, an exhibition by Los Angeles-based painter Kara Joslyn, marking the artist's first solo presentation in Korea.

Pull the hook out, please throw me back in Wherever is deepest, I can swim ... —lyric from Ryan Caraveo’s "Bubbles" (2018)

The hook is not only a fishing device, but also a trap, an attraction, surfing the top of a breaking wave... In short, something arouses our unconscious desire, which often goes hand in hand with transgression.

Growing up in San Diego, Joslyn often swims freely in the ocean. Water is the Jungian symbol for the unconscious mind. Jung famously coined the term collective unconscious—the incognizance of memories, impulses and desires that is common to mankind as a whole.

To embrace the notion of Americana is to place an emphasis on the self, which is the source of the cultural ideology of consumerism and other doctrines that are responsible for alarming destruction in our present days. Joslyn’s solo exhibition Please Throw Me Back In The Ocean is a presentation of recent paintings that range in scale from intimate to larger-than-life. Unfolding, across three rooms and two floors, these works bring together the artist’s reflection on her cultural experience of living in California and her inquiry into the collective desires and memories conditioned by the consumer capitalism of Americana. Fiercely precise and remarkably illusionistic, Joslyn’s paintings—in grayscale and stark contrast—of a constellation of geometric and angular paper sculptures of seashell, compass rose, doll, mask and hook are derived from photographed images in her collection of books on paper craft.

In order to achieve the utmost sense of verisimilitude, sometimes on a monumental scale, for example in, “And you say - Stay (I Missed Me)” (2023), an iridescent blue painting of an anchor, the artist has developed a punctilious painting process. She first scans the image, then uploads it in the computer for editing. After printing out the digitally manipulated and enlarged sketch, she traces the lines to transfer the image onto the masked-off canvas, then maps out areas of light and dark, before painstakingly removing tapes section by section to airbrush thin layers of a combination of black acrylic and optical pigment powder. The mixed paint gives the monotone a psychedelic, iridescent glimmer. Interested in exploring the representation of three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface, she experiments with variations in the density and tone. As if drawing on a white paper, Joslyn does not use any white paint; all the white in the painting is the exposed surface of the canvas. Vija Celmins once said, “I like to see the paper, because the paper is a player.” Canvas is a player for Joslyn. She goes one step further by turning up the contrast in favor of an overall sharp focus. As a result, the textures of many objects in her paintings seem transformed from flimsy paper to solid and weighty materials. Meticulous planning concerns the artist a great deal, because her painting process is nearly irreversible, which allows no room for regrets.

The composition of her painting is often straightforward, typically occupied by the frontal close-up of a single object, such as in, “my whole world's turned amphetamine blue, now I'm livin' without you” (2023), a seashell floating in a void. However, in, “NOPE (After Magritte and Peele)” (2023), a flower looms above layers of rippling waves, the composition nods to René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images.

Similar to Vija Celmins, Joslyn directs her attention to photographs found in books. Clearly relishing the painterly possibilities afforded by folded and cut white paper and its cast shadows, Joslyn works the painting out with her tight rendering technique to achieve the uncanny resemblance of the nostalgic black and white photograph. Of course, it is impossible to not notice her blatantly photorealistic style, mimicking the smoothness of the lithographically printed commercial photograph; however, her work does not passively adhere to the photographic information. Standing in front of her painting, the viewer is unable to mistake her process-based painting that has a very physical presence for a mechanically produced photograph of an immediately available product. By successfully combining the photographic real and the painted unreal, the artist calls attention to the intense process of archiving, selecting, re-photographing, editing, scaling up and painting. Painting, a manual and laborious action, is what Joslyn hopes us to see, even its imperfection: slight misalignment of the lines here or a faint residue of the masking tape there. But what messages does she try to convey in her paintings with no background, no suggestion of place, almost no other colors than black, white, and sometimes blue, nothing but the minimal of isolated American vernacular forms and objects? The interplay and the conflict between the world represented in her visual illusion and the actual material reality situate her painted image between a reproduced copy and a fragment of our collective unconscious, teasing out the profound irony in the ideological and historical construction of Americana, where the seemingly innocent vernacular culture, such as paper craft, is deeply embedded in American consumerism.

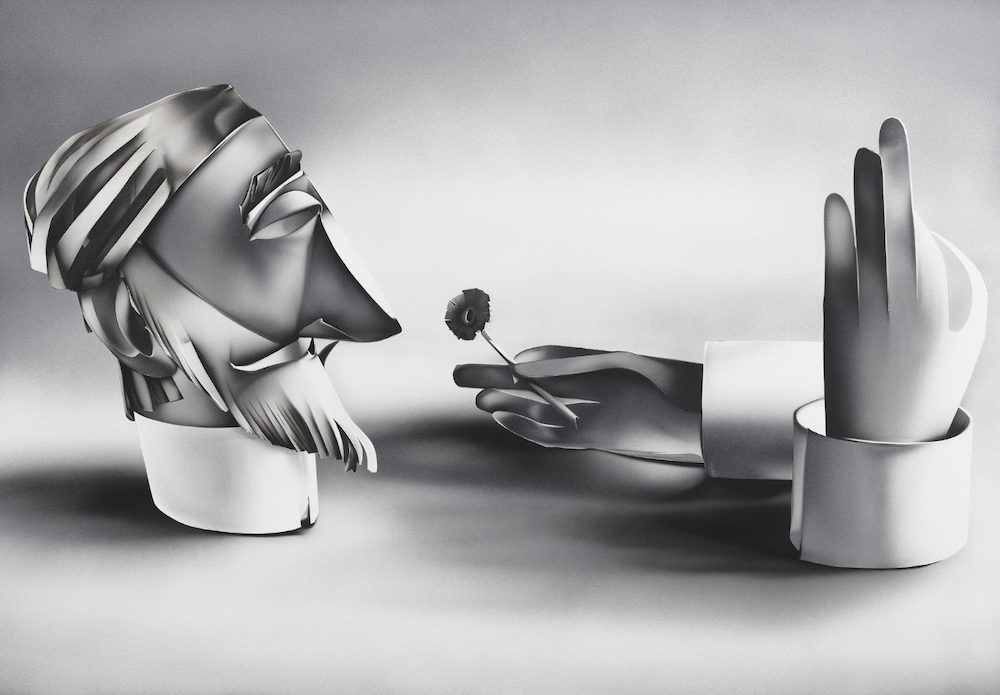

At the heart of Joslyn’s practice is not only the nuanced detail and the extraordinary control of the medium, but also a desire to evoke a possible space from the neutrality offered by photographed images of kitsch and banal vernacular culture for self-expression and social critique. Such is her tongue-in-cheek painting, entitled, “Love, peace and harmony? Oh very nice, very nice. But maybe in the next world. (The Decollation of Alan Watts / Grooving on the Eternal Now as Sacrament)” (2023), that depicts the head of the bearded man, whom the artist interprets as Alan Watts—the unofficial spiritual leader of the Hippies and an intimate of the Beat Poets—closely grouped together with a hand lying horizontally holding a flower towards him and another hand in a vertical position. The composition that reminds the viewer of the theme of vanitas—a style of still life painting in art history, symbolizing mortality and the worthlessness of worldly goods and pleasures—speaks to a visual and emotional anxiety, reflecting the deep cynicism in contemporary life. Clues are also evident in many paintings’ titles, which are lifted from various songs to hint at the underlining narratives and stimulate a synesthetic association of form and image with sound and lyric.

It then makes sense how Joslyn deliberately brings forth on the canvas her consideration of reproduced photograph as, what art historian Linda Chase called, “an object with its own phenomenological presence,” factually and metaphorically, to challenge the language of representationalism and to unapologetically reveal the shadow of the American Dream. Given the history of Realism and its tie to political commitment and the short lived phenomenon of Photorealism that was devoid of social critique, one cannot help but wonder about the future of the currently resurgent interest in Hyperrealism that has been spearheaded by artists such as Kehinde Wiley and Sayre Gomez, and now Kara Joslyn. — Essay by Danielle Shang, Los Angeles-based curator, writer, and art historian