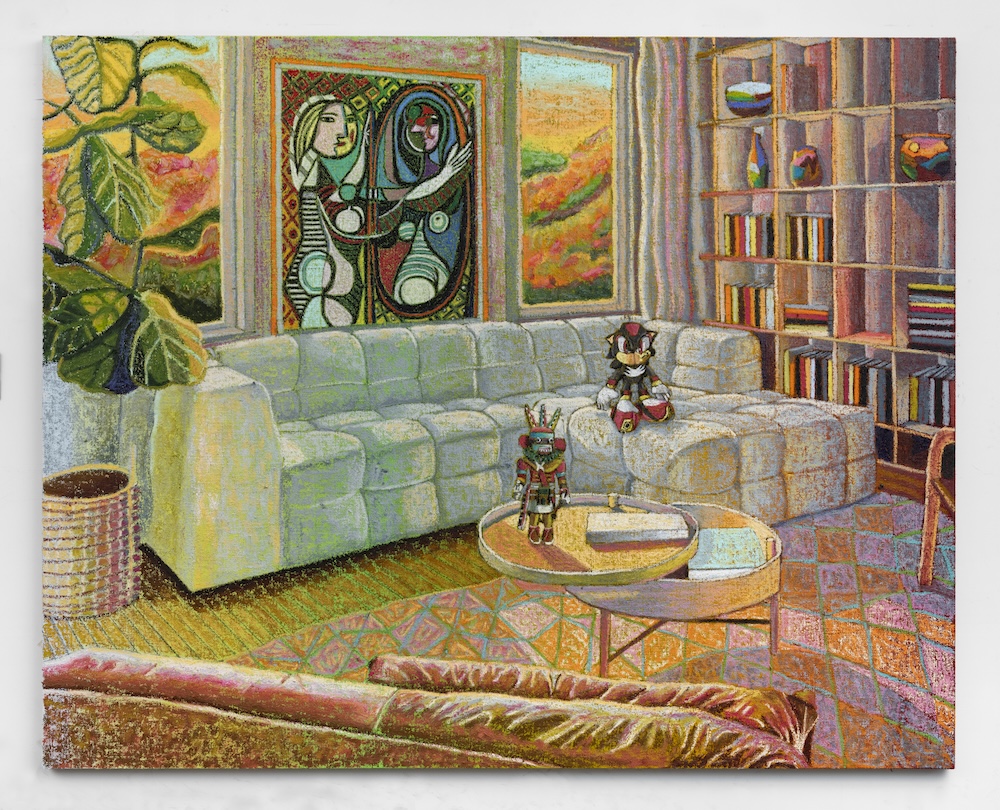

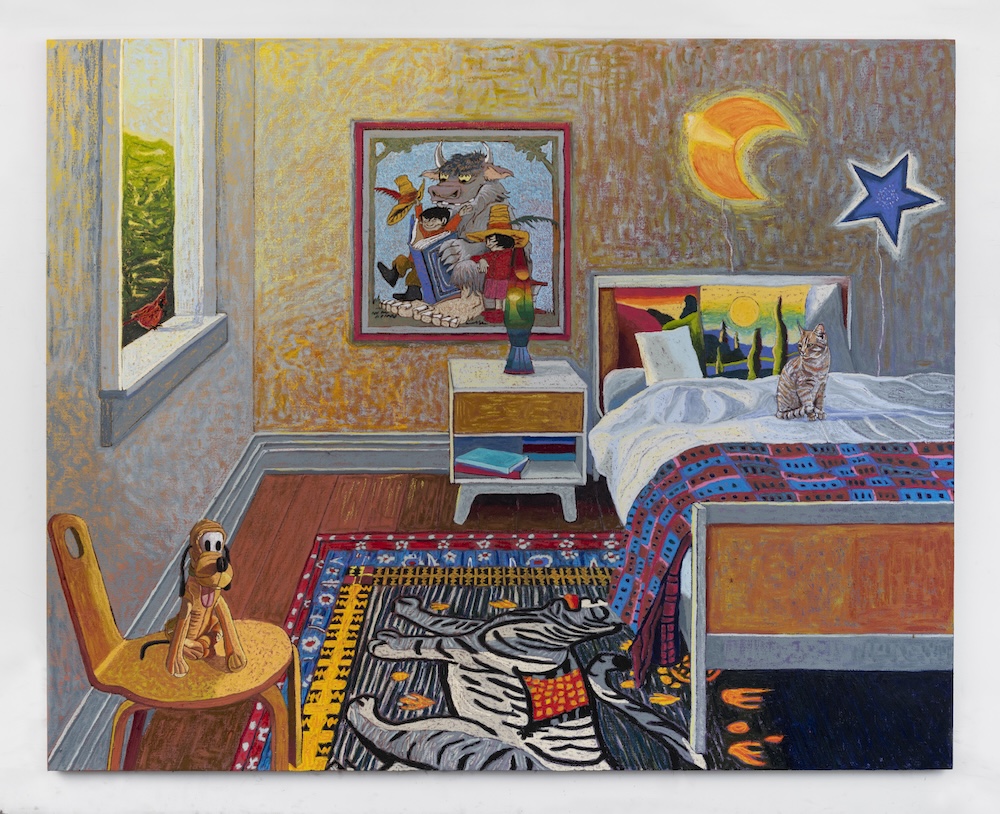

Derek Eller Gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition of new paintings by JJ Manford entitled Hayden Rowe Street. Utilizing oil stick, oil pastel and Flashe paint on burlap stretched over canvas, Manford curates imagined domestic spaces filled with an array of historic artworks, objects, textiles, furniture, and animals. Simultaneously painterly and cinematic, his recent works highlight the coexistence of our manufactured and natural world.

These paintings are all about life, as it turns out. The artist’s as well as ours, as viewers. We bring to his work many of our own associations and memories, especially those of us who grew up in the same generation as him. The absence of the human figure—in spaces depicted almost life-sized—makes the viewer sensitive of their own embodied presence. As if to underscore this fact, Manford has recently made room sized rugs and ottomans based on those depicted in several of his paintings. The designs are his, but initially existed only in the paintings themselves, highlighting a constant give and take between art and life that occurs in his work.

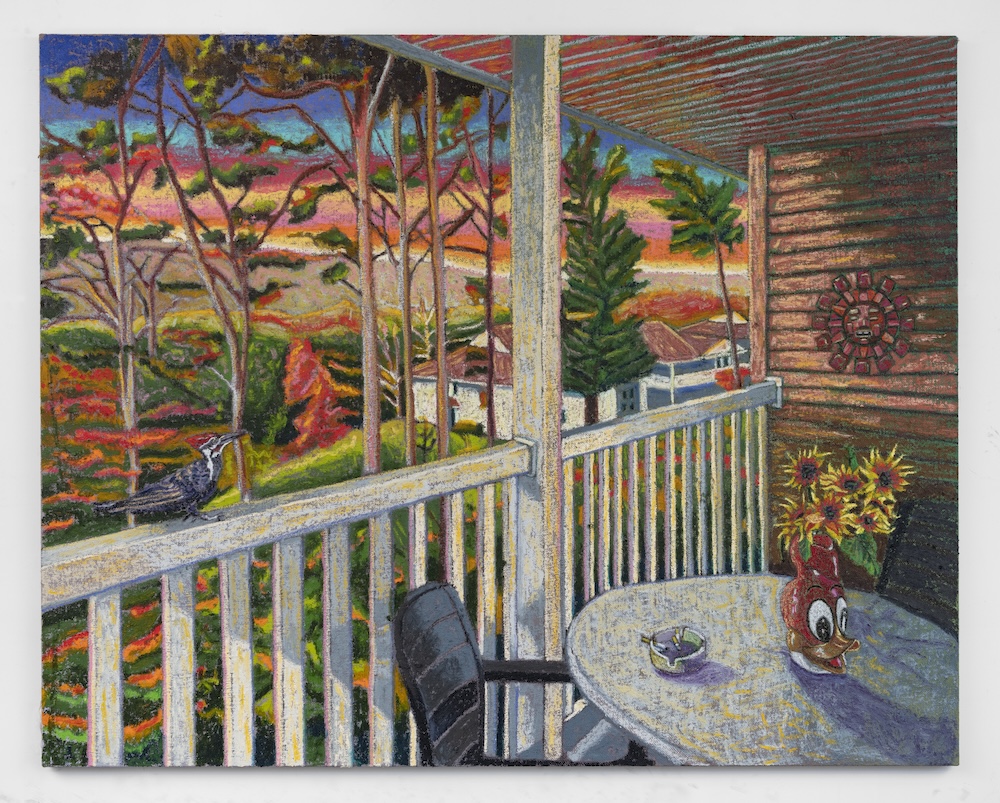

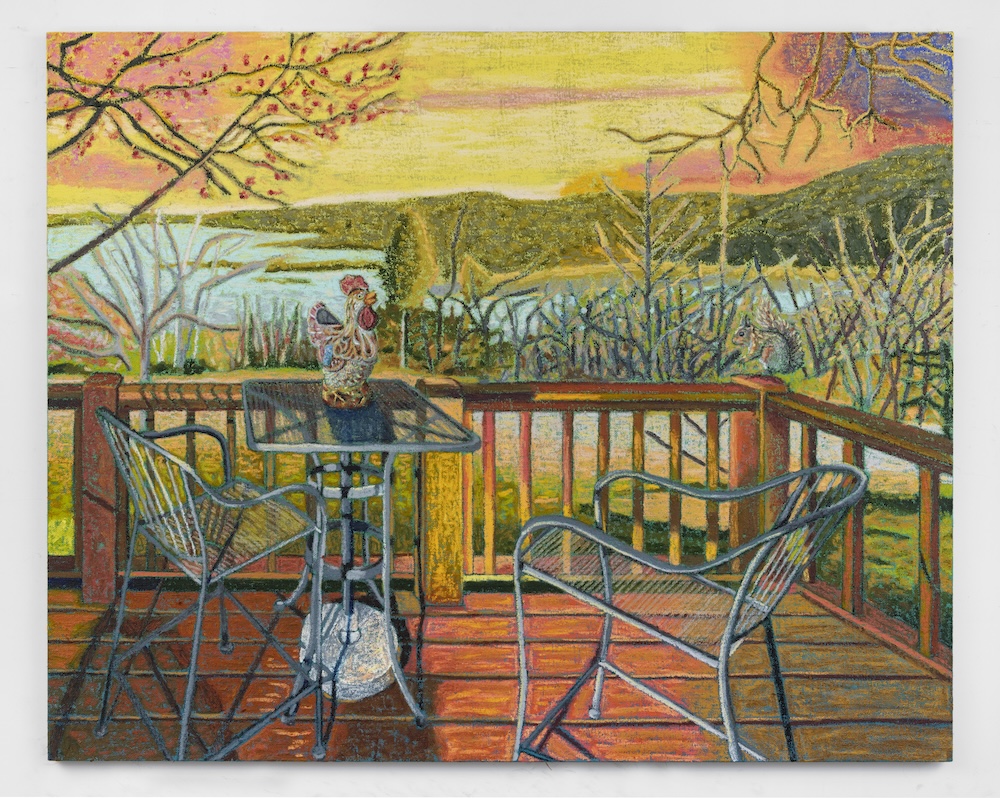

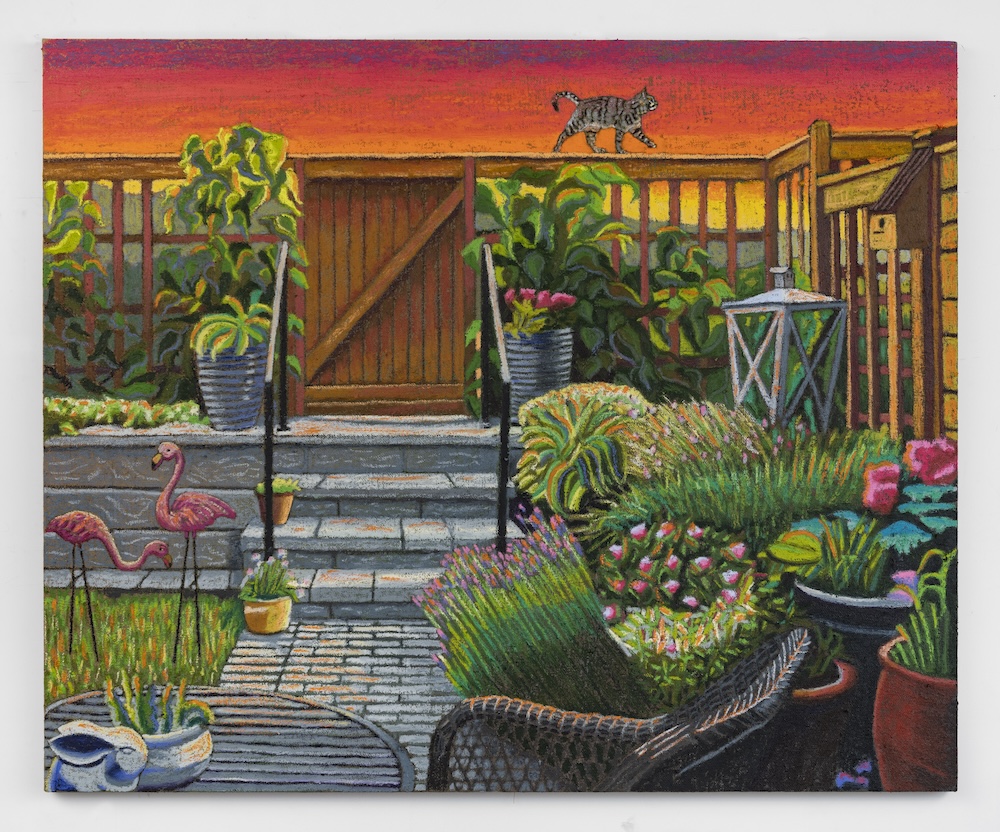

Within the last year, landscape has become more prominent in Manford’s paintings, in some cases displacing the interior as the main compositional element. While parts of the landscape come from stock photographs as well, they allow Manford a much greater range of expressive potential, in terms of both composition and choice of palette. Like his rugs and ottomans, the landscape gives him freer reign. Yet his landscapes are always anchored by an architectural element: a doorframe, a wooden deck, a backyard fence. This is not landscape experienced raw, but rather mediated by domesticity. This particular compositional strategy of balancing the interior and outdoor spaces, oddly enough, throws into relief just how domesticated the landscape already is.

Manford’s work broadly inhabits a similarly liminal space, somewhere between invention and appropriation, painting and drawing, experimentation and design, inside and outside. It is carefully tuned, like his color combinations. Musical analogies are appropriate in this instance, as he himself has admitted. These are not paintings about life, per se, but they demonstrate that longing of wanting to give life to something. But that has long been the domain of artists—to bring inanimate matter to life. Manford succeeds in that regard, if only to remind us that sometimes even the most banal parts of life can still be both wonderful and strange. —Gilles Heno-Coe