“The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.” – Antonio Gramsci

Jeremy Olson’s latest solo exhibition with Unit London places his familiar cast of otherworldly creatures at the centre of an apocalyptic world. this time of monsters draws its title from Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s reflections on interregnum. Interregnum, an ancient Roman term, signifies a period of long transition between historical stages. Olson situates his exhibition in this state of in-betweenness, commenting on our current period of societal, political, economic and environmental uncertainty. Throughout these suggestions of disaster and collapse, however, Olson’s exhibition never extinguishes a sense of hope and humour. Despite appearances, these monsters are depicted as kind and nurturing, confused and introspective and, sometimes, they just want to party.

Olson has been attracted to the concept of monsters since childhood, an interest that stems from his love of cinema. The artist grew up watching scary movies, the 1950s Godzilla films and David Cronenberg’s body horror. As an adult, Olson’s fascination with monsters takes shape in their potential meaning as something metaphorical, socio-political or psychoanalytical. Here, the notion of a monster is an emblem of upheaval and immense change.

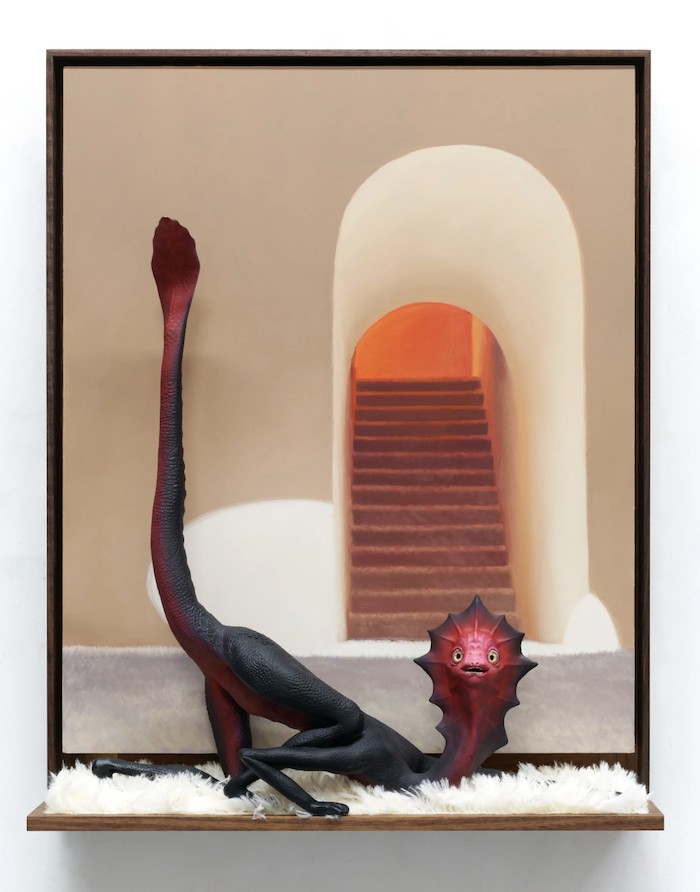

In particular, the artist’s sculptures bookend these concepts of catastrophe. The largest is a diorama of a monster with a child, reclining in a decimated sports arena. The lizard-like creature itself is an obvious reference to Kaiju (Godzilla) and the composition is reminiscent of architectural models. The monster holds up the carriage of a destroyed monorail, questioning its meaning with a shocked expression, while simultaneously nursing an infant. Olson plays with perspective, not only with physical perspective through the scale of his sculptural composition, but also with our own perspective of the monstrous. Here, the artist unexpectedly explores the subjectivity of a monster, reconciling it with something human by encouraging us to relate to its confused expression and its maternal relationship. Similarly, Olson’s smaller sculptures humorously conflate the monstrous and the human as man-made structures are built on the remnants of long-dead monsters. A rollercoaster sprouts from a decaying reptilian foot and a children’s slide grows from a clawed hand. These incongruous references to leisure and play represent Olson’s overarching ideas of rebirth and rebuilding.

Despite Olson’s explorations of the apocalyptic and the catastrophic, this time of monsters remains imbued with the artist’s characteristic sense of humour. His anthropomorphic creatures are instantly relatable as they are unerringly distracted by a screen, a drink or by each other as the world comes to an end. this time of monsters takes pleasure in the present and reminds us of the possibilities that can manifest in difficult circumstances, striking a balance between a sense of acknowledgement and hope. Olson’s depictions of these monstrously abstract fears inevitably give way to universal feelings of the interpersonal, reminding us always to see ourselves in others.