Carl Kostyál is delighted to present a dual exhibition of new works by Indonesian painter Roby Dwi Antono and English painter Felix Treadwell, both their debut London exhibitions with the gallery.

"We are able to find everything in our memory, which is like a dispensary or chemical laboratory in which chance steers our hand sometimes to a soothing drug and sometimes to a dangerous poison." —Marcel Proust À la recherche du temps perdu, 1913-1927

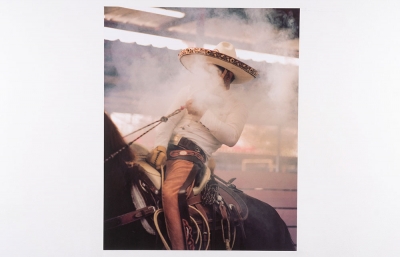

When Proust’s narrator, Marcel, eats the crumbs of a madeleine dipped in limeblossom tea, it triggers a process of remembering that brings his past to life. At first the narrator describes himself as being struck in a way that captures his attention. He is not sure what this sudden awareness means, but he conjectures that it was his tasting the madeleine soaked in tea that brought about this startling feeling. He tastes it again. The same feeling occurs. But when he tries a third time, the feeling is diminished. After much effortful concentration, Marcel finally comes to realise why the tasting experience is so potent: it is anchored by a long-buried memory that is gradually brought to the surface of consciousness. At this point the narrator recalls his aunt Léonie’s bedroom, where on Sundays she would soak pieces of madeleine in her limeblossom tea. He remembers the old grey house in Combray, the gardens, the streets and the square of the small town. From this beginning comes the vastoutpouring of Marcel’s memories of his past life. Dreams and memories – of their childhood, of loneliness and salvation from it, of moments of happiness, of melancholy and of the cloak of ever-present existential angst – are the elements that infuse the works of both Dwi Antono and Treadwell, connecting them in a way that is at once poetic and unexpected.

The act of drawing, central to both their practices, is in abundant evidencehere – lines drawn with bold and voluptuous strokes, tracing the hazy forms of these involuntary memories on canvas, bringing them to new life. This is painting that seeks to express a private, interior world – those otherwise unspoken, ungraspable thoughts that are often more vivid to us, and felt more profoundly, than our ‘real’ worlds.

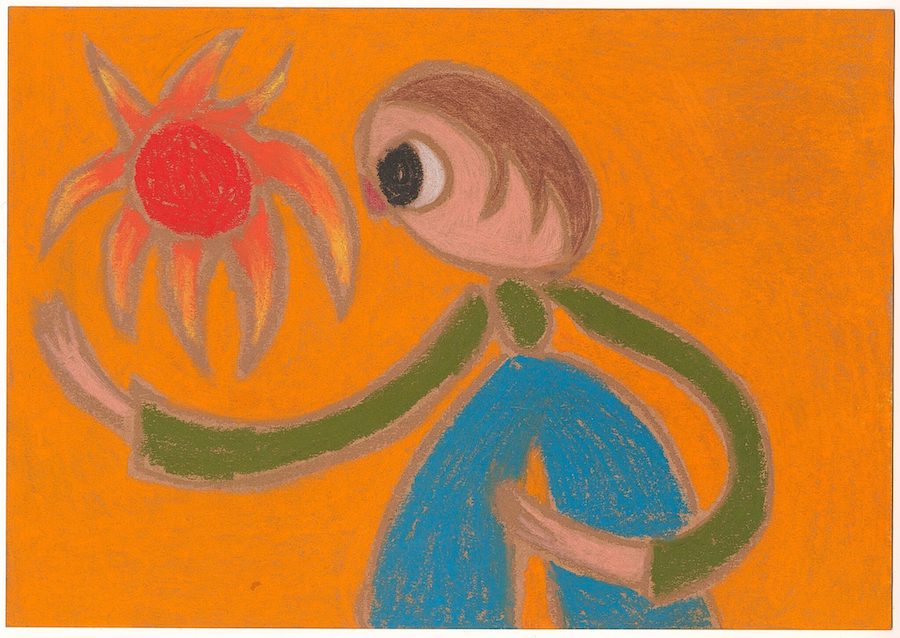

Dwi Antono, whose wild-eyed childlike faces, richly rendered in an acid, almost neon palette of thick oil-stick, stare out at us, over-sized, wild, at times fearful or playful – their disproportionate, irregular lines full of energy and immediacy, his compositions imaginative, naïve, and spontaneous – has described, in Proustian detail, a similar memory, acutely poignant because it marks what he remembers of the beginnings of his artistic self:

“Back in primary school, when I wanted to go and play with my friends, I would go visit my father in his blacksmith workshop to ask for pocket money. At that time, he was one among many blacksmiths in my village and I can still vividly picture how busy the workshops were. That small bamboo house was home to the distinctive smells of heated steel being moulded into household and farming tools. The rhythm of the rattling and thumping of iron bars slowly became music to my ears. Outside the workshop, there was a big tree and under its shade, customers would sit on an old teak bench, waiting for my father to repair their tools. I liked to pick a few pieces of charcoal from the piles lying around, waiting to be used as hot coals to soften the iron. I used that charcoal

to doodle on the streets in the village.”

He has described these works as his attempt to bring back the soul of a child that may have been lost, to visit the memories floating on the surface and to dive deep into those buried below. Their vivid and gestural force is reminiscent of the CoBrA artist Karel Appel, who, like Dwi Antono, attempted to return the mark making of a child, to circumvent adult logic and intellect in his

painting.

"All grown-ups were once children….but only a few of them remember it." —Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince, 1943.

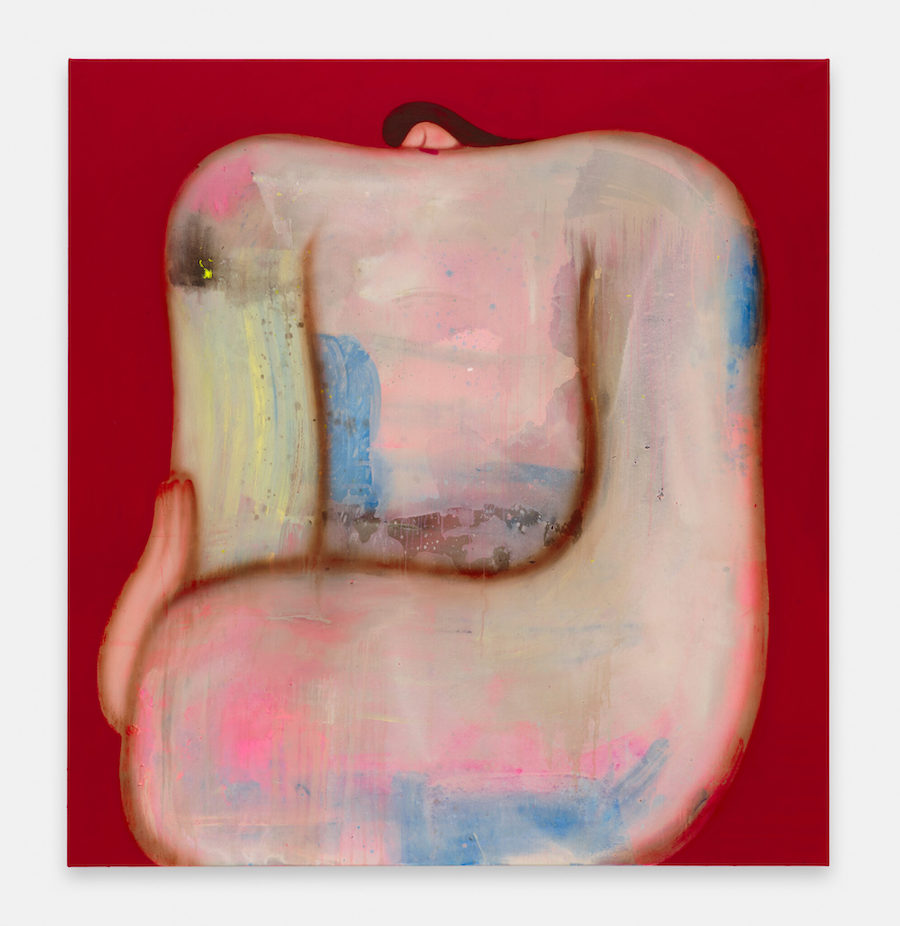

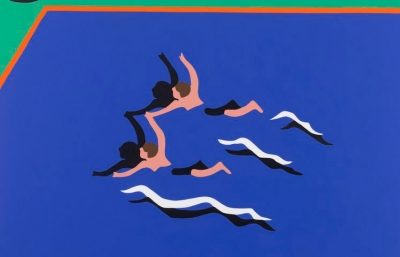

Felix Treadwell’s paintings have a wistfulness about them, a dream-like sweetness. Their grounds are flat and uniformly monochrome. His young protagonists’ figures limbs loom with the sculptural presence of Brancusi or Moore, filling the picture plane, their heads small. They sit, stand or move in childish wonder, together or alone, the hopefulness of a rainbow held in their hand. They are suspended in space, often wrapped or bound together in harmony – here, they appear to have found peace, albeit a somewhat melancholic one. “I guess, in my work, I have always been returning to my childhood or youth and looking at and longing for something I wished or wanted to have, looking at how nostalgia affects one.”

The hypnotic, other-worldly presence of his figures stems in part from their fluid movement, created with a combination of spray and acrylic paint in a deliberately muted, gentle palette. In their stasis and quasi-abstracted form, they recall the exaggerated detail of Domenico Gnoli, the trippy innocence and awkwardness of Zebedee, Ermintrude and Doogal in the British children’s television series The Magic Roundabout (BBC, 1965), more than an aesthetic of the post-digital age, but their simplicity is similarly deceptive. These pareddown compositions are an antidote to the speed and surfeit of imagery we are subjected to daily via social and other media, allowing for a slowing down, a moment of quieter contemplation, their deliberate simplicity both soothing and

intriguing.