The lyrics to Ode to Joy, the triumphant final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, were adapted from Friedrich Schiller’s 1785 poem celebrating strength in unity and the “brotherhood of man.” Beethoven’s version has inspired leaders of political movements as disparate as Mao and Hitler and the European Union—the latter currently employs the piece as the Anthem of Europe. Paradiso, or Paradise, is the third and final act of Dante’s Divine Comedy, which follows the soul’s ascent to heaven following its time in purgatory. With Ode to Joy, Ho Jae Kim’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles and his first with Nicodim, the artist juxtaposes the two poems in an attempt to find equilibrium between chaos and utopia, neither of which he believes can be sustained without periods of the other.

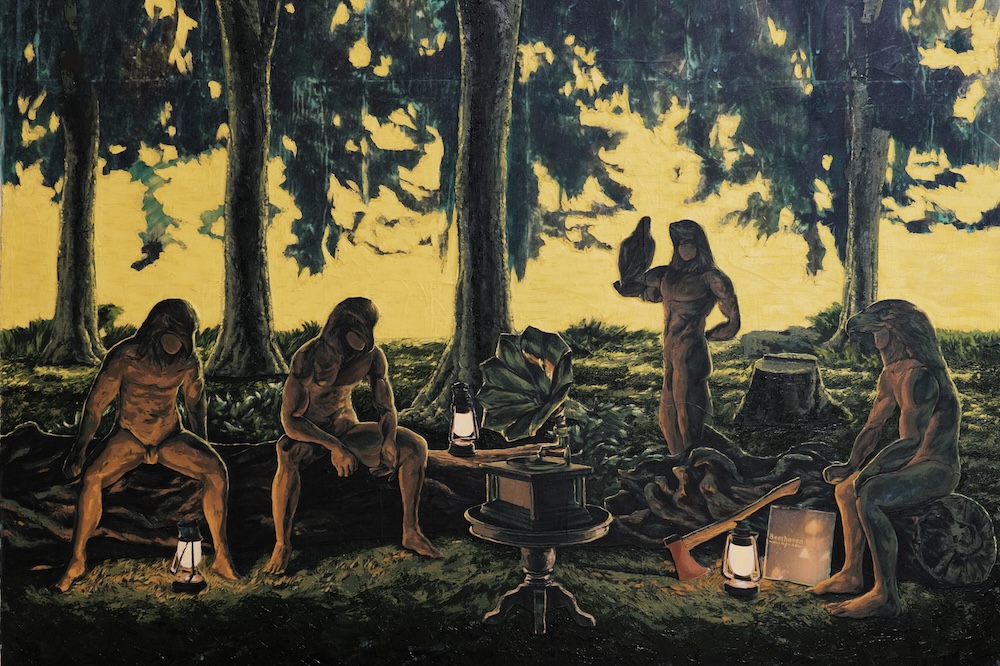

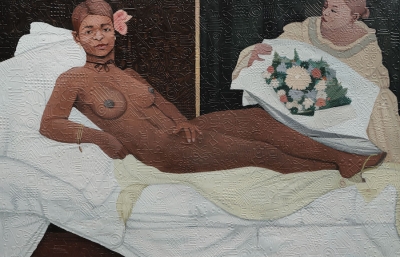

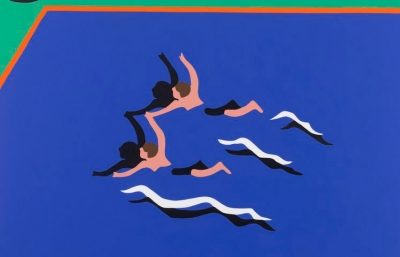

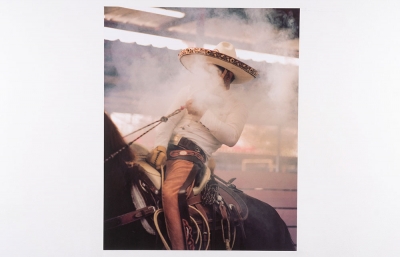

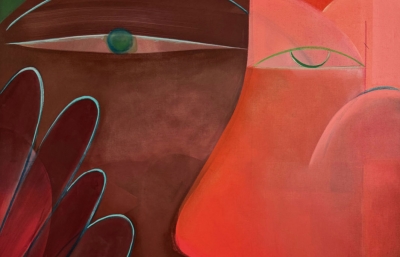

The exhibition consists of three series. In Utopian Carousel and the five The Hunt of the Monster works, Kim imagines his own preamble to Paradiso, in which the viewer is led through various garden scenes that alternate between relaxation and battle. Kim leans heavily on Dante’s notion of purgatory here. His figures that exist without choice are (sometimes literally) stuck on a carousel, condemned to circuit the same stretch of garden for eternity, while those who imbibe in their own free will might either be rewarded in the hunt or damned to expire alone. Some of the characters lived, all of them will die. Kim’s second series features the lyrics to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy etched on Roman ruins. As Beethoven’s Ninth has witnessed time and time again, even the proudest of empires eventually falls, the calamity of its remnants providing platforms and fodder for future chaos and utopias.

Finally, Kim’s epic, two-and-a-half meter The Garden depicts a sort of equilibrium between the anarchy of the garden and a version of state-implemented utopia on top of it. Though the edges are crumbling, a griffin, a symbol of stately power, sits proudly at its center, acutely unaware of its own fallibility.

Kim’s process itself is an allegory for the narratives contained within his work. To create each canvas, he starts with an image transfer and builds it up with layers upon layers of enamel before carving it down and recreating an approximation of the original image on top. It is a constant push-and-pull between chaos and order. Like the images from which Kim begins his paintings, history is often flattened into ideological caricatures and recycled to service contemporary power structures. With Ode to Joy, Kim labors to demonstrate the poetry, nuance, and depth that initially illuminated them. This work is alive.