Emma Webster’s eerie compositions are invitations to travel beyond traditional vistas and into seductively hybrid environments that metabolize, materialize, and alchemize. Rendered in oil paint, her landscapes are simultaneously imaginary and familiar, gravity-defying yet abiding an internal order. To arrive at this logic, the artist methodically works and reworks her compositions, distilling them through various media and technical processes: pencil sketch, preparatory drawing, collage, sometimes sculpture, virtual reality and augmented reality, digital rendering, and ultimately painting. Her process is both analog and technological, traditional and speculative. In this regard, Webster is a decidedly twenty-first century landscape painter, one that subverts convention (like plein-air painting) to virtually paint from the inside, outside, and underside of unlikely panoramas.

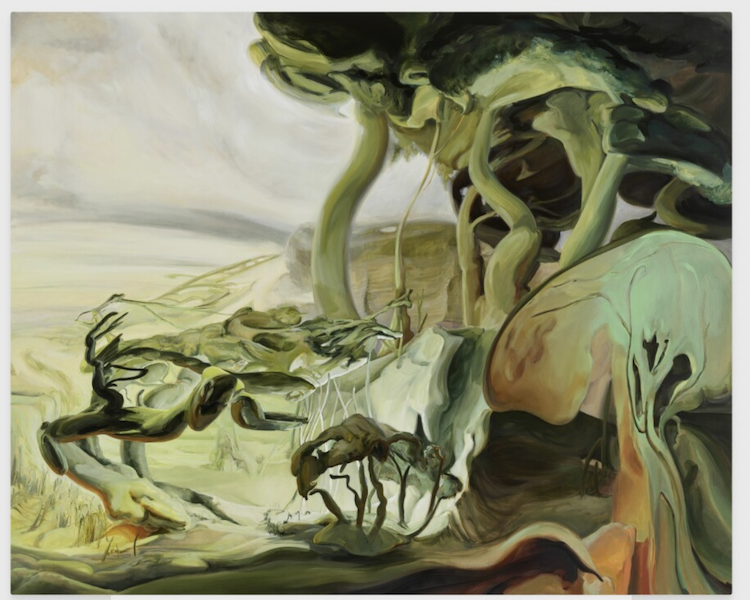

Aloethylene, for example, presents a view onto a thick grove of tree and rock-like forms perched at the edge of a cliff. Beyond it are signs of water, sky, and hills. This verdant grove of tendrils, branches, and foliage seems to be illuminated from within, casting shadows at the outer edges of its composition. Or are the shadows forming a cave, a dark forest, or a brewing storm? It’s a formal ambiguity that stops short of all-out abstraction. In this world—as in all of Webster’s paintings—there are no signs of human life, and even the flora and fauna are alien. All is chimera. As the ambiguous forms merge with the landscape, their significance—as signs of life, characters in the narrative—dissipates into low resolution while the shapes around it are bumped into high resolution.

The Romantic English landscape painter J.M.W. Turner famously said, “there is a sketch at every turn.” Sketching is as central a component of Webster’s practice as painting. “Sketching is a simulation of what a painting could be,” explains the artist, and it’s no surprise that she considers algorithmic simulations another form of sketching. In 2020, around the beginning of the Covid-19 stay-at-home order, Webster was given an Oculus VR headset by a friend. With more time to herself, she delved into the possibilities of the tool, eventually incorporating VR into her studio process. Sketches and drawings from the page are scanned into a VR program where they are given three-dimensions. The artist can turn the image-as-object, thrust it sideways, or see what it looks like from above and below. Then the artist breathes life into the sculptural, digital image, giving it volume and lighting with Blender rendering software. At this stage, Webster achieves her otherwise impossible visions: she can trap light in holes in the physical/picture plane, cast shadows where otherwise none would exist, elongate or foreshorten environmental elements, or experience what it feels like to be inside the image looking out. As with a video game, she enters these worlds and tweaks their preprogrammed cause-and-effect to produce an uncanny rationality.

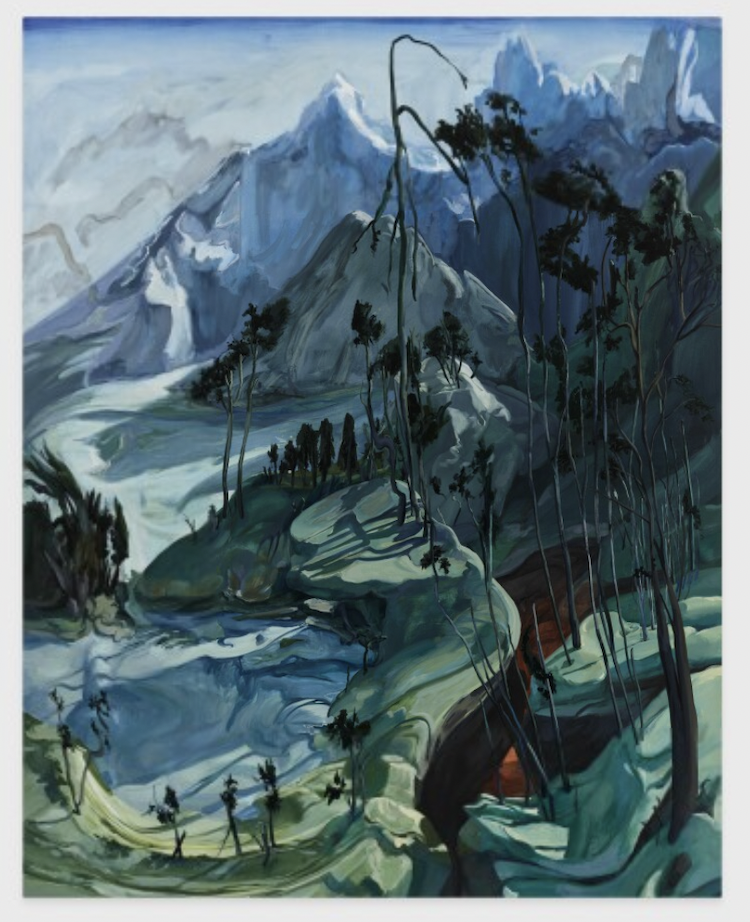

After the artist is satisfied with her rendering, she outputs an image that becomes the direct source for her paintings. From here, the image is implicated by painting alone, a set of formal concerns that Webster calls “solving painting problems.” For her, painting is a question of pushing the image to its extreme. “Exhaustion is not the limit,” she explains. The work Field Guide is a strong example of this process. A vertical composition, the painting employs traditional atmospheric perspective—a method to create the illusion of depth in which objects in the distance are painted hazier or lighter than those in the foreground—yet its ground is deceptively warped; shadows fall across an uneven topography, which recedes and thrusts in ridges and caverns of painted texture and swirling color. It’s a landscape that references some illusory diorama, a representation of the unreal staged in a digital, virtual outland.

Although the artist is digitally native, Webster is nevertheless a dedicated student of the Masters. Her art historical knowledge and passion for famous painters—among them, French Baroque artists Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin; English Romanticists John Constable, John Martin, and, of course, Turner; Hudson River School painters Thomas Cole and Thomas Moran; Belgian symbolist William Degouve de Nuncques; Hungarian avant-gardist Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka; and American modernists Georgia O’Keefe and Arthur Dove—can be traced in her stylistic flourishes and approach to lighting, volume, and gesture. Webster is wowed by Martin’s apocalyptic vision of Earth and delighted when O’Keefe makes the sublime feel tangible. About Turner, she exclaims, “We’ve been missing his special effects. Look at those pyrotechnics! It’s like IMAX!”

Indeed, these fantastic weather events are both awesome and terrifying. While Webster refers to such hypothetical vistas as being “kicked out of dreams,” she acknowledges the frequency with which unforeseen weather events are becoming reality. Floods, wildfires, tornados, blizzards, and mudslides are increasingly commonplace due to a warming planet, forcing humans to adapt to nature’s unpredictability. “Unreality is a comfortable place to deal with uncomfortable realities,” Webster explains. From this vantage, the artist amplifies and distorts the humbling forces of nature and, like so many artists before her, reiterates the hubris of man. It's a nod to an art historical past and perhaps a hint at a future here on Earth. —Catherine Taft