Carl Kostyál is delighted to present Artificial Emotions by Chinese artist Li Shurui. This is her second solo exhibition with the gallery, following her debut at Carl Kostyál Milan in 2020.

In tech, artificial emotion refers to the simulation or replication of human-like emotions in artificial systems such as AI, robots, or virtual agents and the goal behind creating artificial emotions is often to enhance human-machine interaction, improve user experience, or develop more empathetic and responsive technologies. Think of Spike Jonze’s 2013 American sci-fi romantic drama Her, where Samantha, an artificially intelligent virtual assistant personified through a female voice, whose interactions with its user, Theodore Twombly, allowed it to adapt and evolve, enhancing her personality that eventually turned her into a ‘real’ person, engaged in every aspect of his personal life, without an actual physical presence.

In this sense, we have reached a point where AI, digital devices, and smart technology have effectively encroached on every aspect of our lives. What is our relationship with the machines and AI? How do they impact our psyche, behaviors, and ethics, and would such impact feedback to machine learning? More importantly, aside from proficiency and functionality, what is the impact of technology on the evolution of human civilization? These questions concern not only scientists and researchers but also artists, cultural producers, and aesthetic makers who equally anticipate answers to the questions mentioned above. In the art world, especially those using painting as a primary means of expression, produce work through a medium that is now considered one of the oldest, moreover, whose death has been proclaimed many times throughout the history of art amid rapid advancement in technology.

Li Shurui, born in the 1980s, is among the first generation of China’s economic reforms. Upon graduating from the oil painting department of the Sichuan Fine Art Institute, one of China’s top art schools, in the early 2000s, she moved to the nation’s capital. Gearing up for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the city’s urban landscape emanated thriving energy from ubiquitous construction sites and gigantic LED screens adorning high-rise buildings, coinciding with a time when electronic devices such as digital cameras, mobile phones, and personal computers began to popularize.

Using the digital camera to capture this energy while working as an artist’s assistant, her first painting, Light (2005), depicts the halo of artificial lighting against a dark background. Li’s inclination has always been to render a visual experience in her work that may elicit a physical reaction and even a psychological response in the viewer rather than represent a subject matter. With a digital camera, she began capturing the blinding LED lights throughout the city.

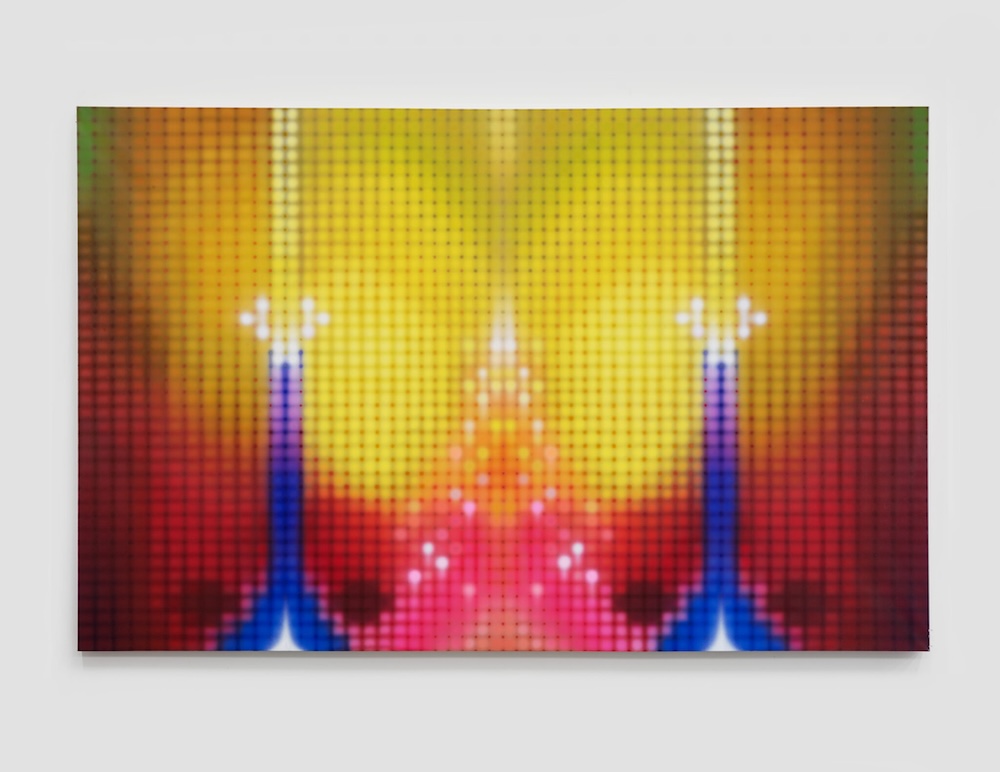

Many have initially misunderstood her works on canvas as Op Art; in fact, her approach may be, at best, described as photo-realist. She first photographs the dazzling dots of light on LED screens and then, based on the interactions of colors, recreates those color and spatial effects with an airbrush on canvas. Instead of inventing a visual icon that many painters repeatedly represent, Li discovered a model that may contain many color schematics based on the laws of electromagnetic waves and the condition of various lighting, natural or artificial. Of course, light has played a fundamental role since the dawn of human civilization, from the invention of fire to electricity and now to the ubiquity of digital devices, which continue to transform our experience of color.

“For me, any visual form, as long as it would illicit strong effect, would be considered to possess visual power.” Li has been exploring the relationship between light and color, using the airbrush as a primary tool for her painting practice, whose intentional choice of giving up the brush, in the context of rapid technological development, speaks to the artist’s acknowledgment of the medium’s evolution. “My paintings not only learn from the visual effects that machines have introduced but engage machines to achieve goals previously unattainable by the hand alone.”

Other than works such as Glimmer of Joy after Deep Sleep, where the direction of color gradations suggests movement, the works on view in this exhibition present another constant factor in the natural world: symmetry. It is a motif found in ornamental art across many cultures as much as in the natural world phenomenon. Einstein deemed symmetry the basis of fundamental law, and the world embodies harmonies. Our sense of harmony agrees with what nature likes to use in her construction of the world, the idea that symmetry and mathematical perfection provide the building principles of the world. Moreover, we associate symmetry with a sense of beauty and attractiveness.

Upon looking at pieces such as Symmetry Makes Face No.1 & Symmetry Makes Face No.2, would those seemingly perfectly and symmetrically aligned color spots along the central axis of the canvas trigger the psychological reflex of configuring them into human faces? And once the vision of a face begins to form mentally, would it reveal an expression that may be attributed to a type of personality or character? Furthermore, do those facial expressions convey any emotion that would ultimately elicit a psychological response in the viewer?

In her recent works, Li Shurui introduced what she calls the “improvisational component,” or what she once considered as ‘flaws,’ in her immaculately laid out plan. Random paint spots spin-off from the airbrush, or even the intentional malfunction of the airbrush that would allow acrylic paint to drip from the perfectly sprayed color spots, would have been rejected by the artist in previous works. This recent feature may be partly an indirect influence from her musician husband Li Daiguo’s responsive and improvisational approach to music making. However, it is even more likely that Li Shurui began to explore the psychological impacts of AI and realized scientists’ foresight that AI would eventually generate their own expressions, moods, and emotions.

“In this time of crossroads, I wonder how we can live with the AI as it forms the independent spirit since humans created it… If the AI becomes faster and stronger than humans, capable of having emotions and needs, would humans still treat it like tools, or would we recognize that we have created a new ‘god’?”

As the physical and digital worlds continue to converge, new types of emotional relationships are emerging between humans and machines. Li Shurui’s practice, in her own words, is “a preliminary integration of the machines and AI” to encapsulate the ethos of our time for future generations. —Fiona He, 2024