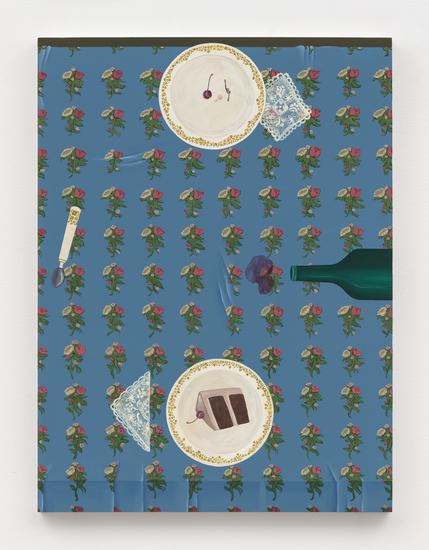

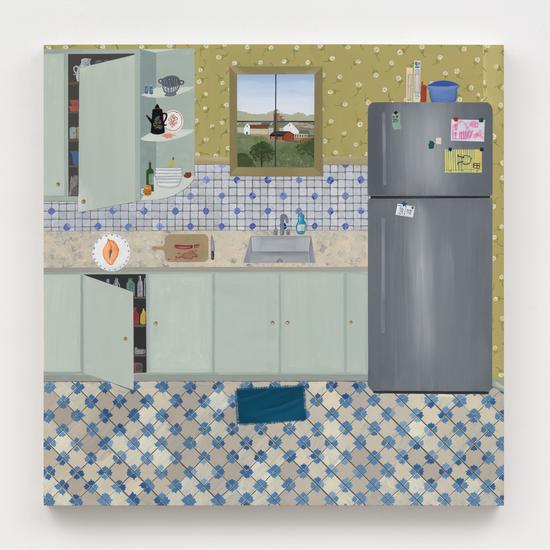

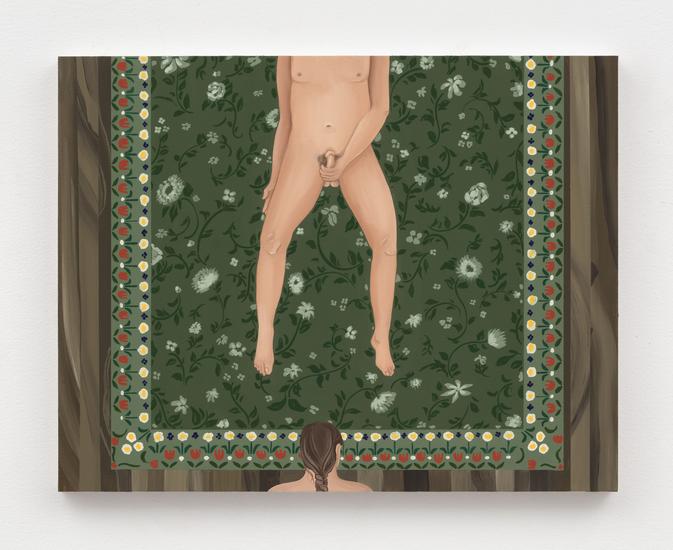

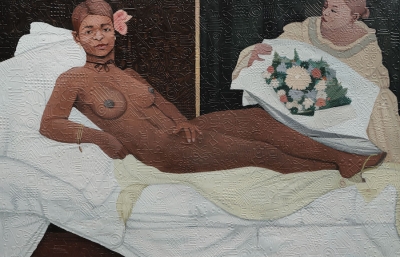

Rachel Uffner Gallery is pleased to present, Reins on a Rocking Horse, Anne Buckwalter’s second exhibition with the gallery. Extending the artist’s exploration of Pennsylvania Dutch folk art tradition from a personal and contemporary lens, the gouache on panel or paper works (all 2023) explore our physically and emotionally compartmentalized selves. Amidst Buckwalter’s precise motifs and sharp geometries, bodies pop from doors left ajar or appear on elegantly-placed mirrors. Impeccably clean-cut interiors coyly hide carnal adventures; repetitious motifs diligently decorate walls, blankets, and tablecloths. Secondary colors of the American middle class living are interrupted by the very reality of the naked skin.

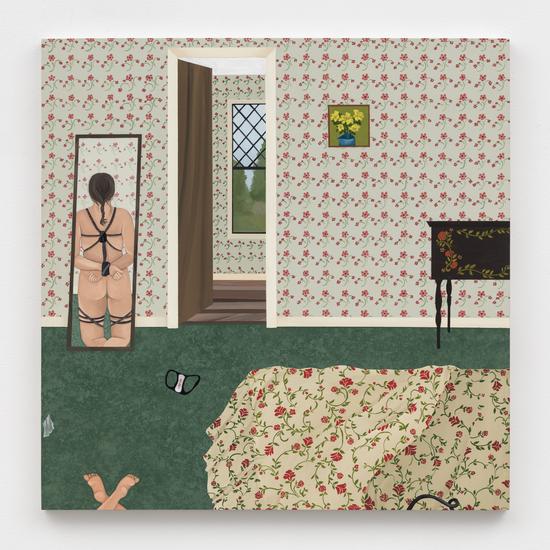

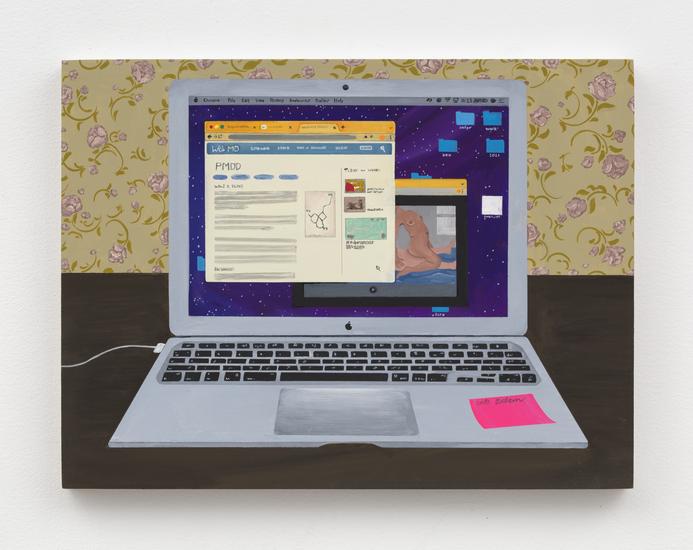

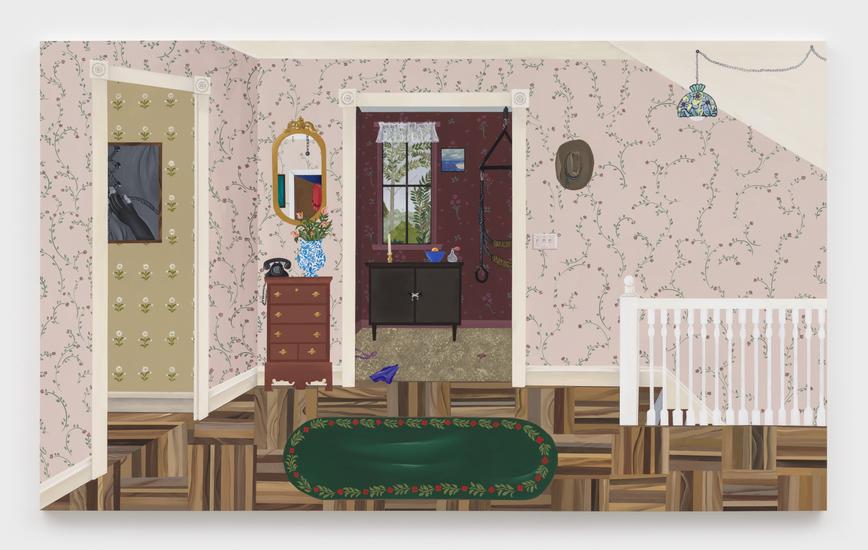

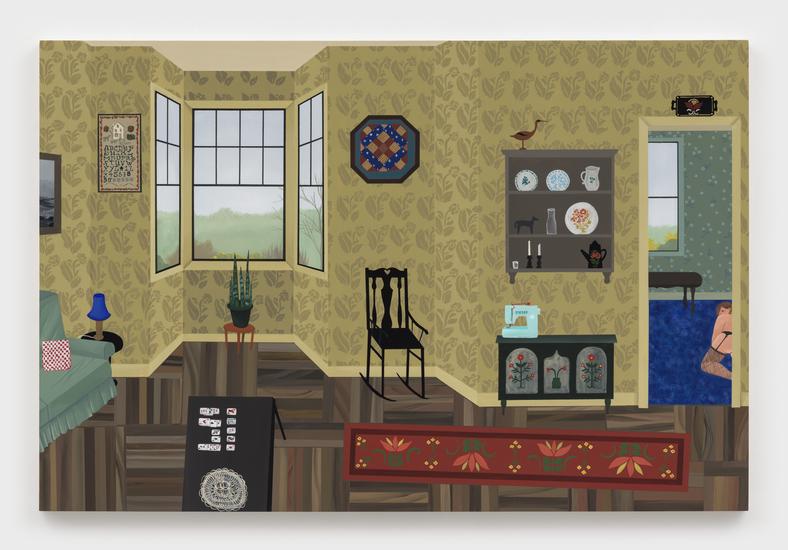

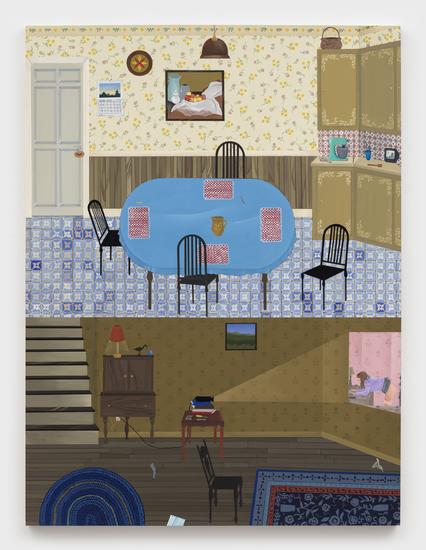

The exhibition’s paintings mostly encapsulate domestic interiors, or occasionally windows into others’ lives, each operating not unlike a body. Orifice-like rooms reveal partial views while objects in pristine orchestrations endure like memories—of the Maine-based artist’s own from growing up in Pennsylvania as well as the homes’ assumed inhabitants. Windows are like deep eyes that sharply glance and are silently gazed back. Each unique in their design, furniture items such as consoles, chairs, shelves, and cabinets quietly occupy kitchens or bedrooms, akin to longstanding remembrances. Or, more personal belongings, an underwear, a belt or a butt plug for example, linger like the mind’s seeping urges into a body.

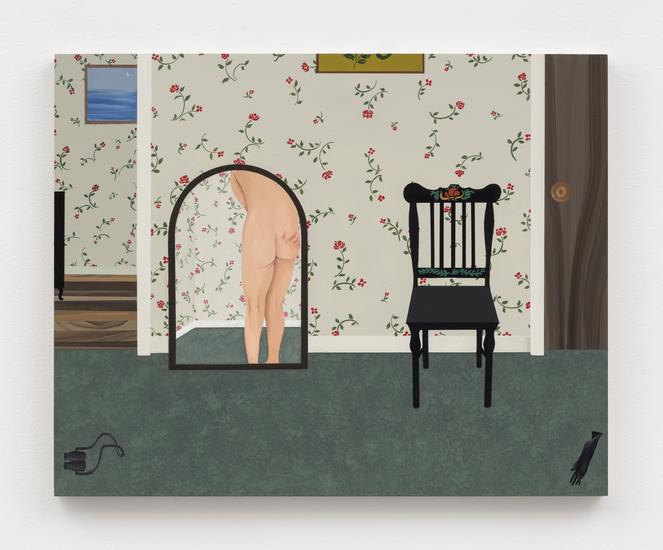

As much as what is captured for the eye, tales left out of sight or kept behind closed doors radiate from Buckwalter’s precise compositions. Both in Pony Tail and Red Right Hand, a mirror carves out a corporal portal to an otherwise neutral interior. A rocking horse and a dimly-lit lamp in the former render a shy environment, mischievously accentuated by the reflection of a single breast on the table top mirror. The latter’s larger mirror kinkily yields a likeness of the body from the rear, revealing the buttocks which may have just been slapped. The rosy shade of the hand mark on the flesh echoes the hue of the wallpaper’s endlessly repeating roses. “Kinetic energy in a language of tidiness,” the artist calls her portrayal of inner fantasies inside contained spaces.

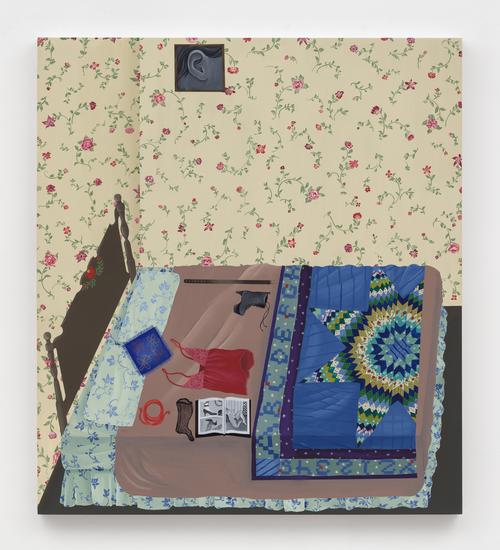

Good Listener relies on objects to illustrate their owner’s mundane forays —similar to elements that build a facial expression, they complete a psychological portrait. Lingerie, a latex boot, and a piece of red rope are carefully lied across a quilt-covered bed; a book with S&M imagery among the neat clutter reveals the absent body’s sexual ventures.

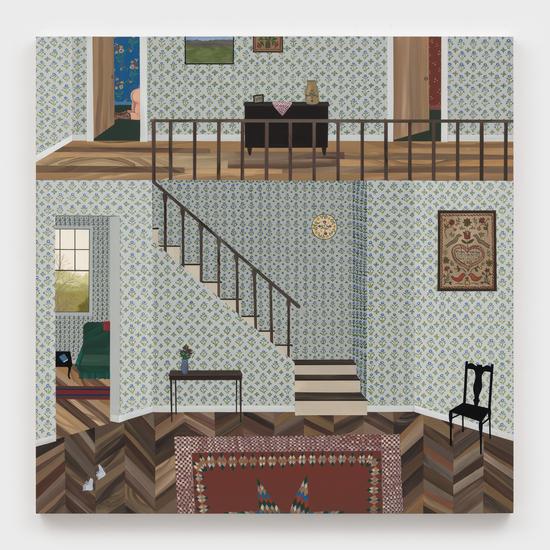

Buckwalter utilizes a perspective that blends miniature painting with a commercial fisheye lens. All-encompassing frames generously span large kitchens with outside vistas, staircases reach to upstairs floors, and living rooms connect to dining nooks. Secrets, fantasies, and gossips, however, linger into the domestic sterility. The viewer’s omnipresent outlook is challenged by the hints the artist seeds about the unseen; settings reserved for domestic labor host carnal rituals, mostly captured in their aftermaths.

Empty Bathroom, Low Battery, and Next Door Neighbors embody a deprived information with depictions of others’ windows. The limited sights show medication bottles and a used tampon in the first painting and the bottom part of someone naked lying over the bed in the following. Binoculars in the final piece signal a peeping curiosity, which offers the onlooker the front a nude woman behind blue drapes. “Looking at a painting, regardless of its subject matter, can feel like an act of voyeurism. You are peering into someone's intimate inner life,” says Buckwalter. In Home Alone, a sprawling interior is dressed in floral wallpaper, quaint furniture, and a pristine equilibrium—the glare on the parquet floors and the details of a doily catch the sharp eye. A half-open bedroom door upstairs unveils someone on their knees, donning nothing but fishnet stockings. Through the cracks of a homey order leaks earthly reveries. —Osman Can Yerebakan