Through June 6, 2021, Amy Sherald, one of America’s defining contemporary portraitists, will unveil new paintings in her first West Coast solo exhibition. On view at Hauser & Wirth’s Downtown Arts District complex in Los Angeles, ‘The Great American Fact’ presents five works produced in 2020 that extend the artist’s technical innovations and distinctive visual language. Sherald is acclaimed for paintings of Black Americans at leisure that achieve the authority of landmarks in the grand tradition of social portraiture – a tradition that for too long excluded the Black men, women, and families whose lives have been inextricable from the narrative of the American experience. Subverting the genre of portraiture and challenging accepted notions of American identity, Sherald attempts to restore a broader, fuller picture of humanity. She positions her subjects as ‘symbolic tools that shift perceptions of who we are as Americans, while transforming the walls of museum galleries and the canon of art history – American art history, to be more specific.’

Sherald routinely draws upon literary references in her exhibition and the titles for her paintings. With ‘The Great American Fact’ she is referencing an 1892 book by educator Anna Julia Cooper, who wrote that Black people are ‘‘the great American fact’; the one objective reality on which scholars sharpened their wits, and at which orators and statesmen fired their eloquence.’ Sherald here employs Cooper’s statement as a framework for considering ‘public Blackness’ – the way Black American identity is shaped in the public realm. Her paintings celebrate the Black body at leisure, thereby revealing her subjects’ whole humanity. Sherald’s work thus foregrounds the idea that Black life and identity are not solely tethered to grappling publicly with social issues, and that resistance lies equally in a full interior life and an expansive vision of selfhood in the world.

With the new paintings on view at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, Amy Sherald continues her effort to ‘paint the things I wish to see’ by depicting Black Americans in scenes of leisure and centered in stillness. Employing techniques long central to the art of portraiture, Sherald underscores the identity of her subjects through visual cues and objects familiar from contemporary Americana – the Barbie logo, fashion denim, surfboards, a picket fence, a convertible – to reinforce their inseparable connection to the nation’s historical and cultural fabric, and to reconstruct conceived notions and reinforce the multiplicities of Black American life.

At the heart of Sherald’s practice is her ability to push the boundaries of the medium of paint itself. Three works in the exhibition build upon her technical advancements through the use of monumental scale, figure groupings, and iconographic imagery to hint at unseen narratives. ‘As American as apple pie’ (2020) depicts a couple standing in front of a yellow house in a composition that conjures Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’ (1930). But instead of a pitchfork, a cameo, and a wary expression, Sherald’s couple is depicted with the accoutrement of contemporary pleasure. In a pose evocative of James Dean, the man in this painting directs his gaze at the viewer while leaning confidently against a retro convertible. Beside him, a woman wearing oversized sunglasses and a pink T-shirt emblazoned with the Barbie logo, grasps a plastic cup in the shape of a flamingo. Similarly, ‘An Ocean Away’ (2020) depicts two figures together. Set in the dunes of a beach, this painting presents a young boy wearing a surfer’s wetsuit and regarding the viewer directly. The adult man beside him casts his eyes toward the horizon from the spot where they stand.

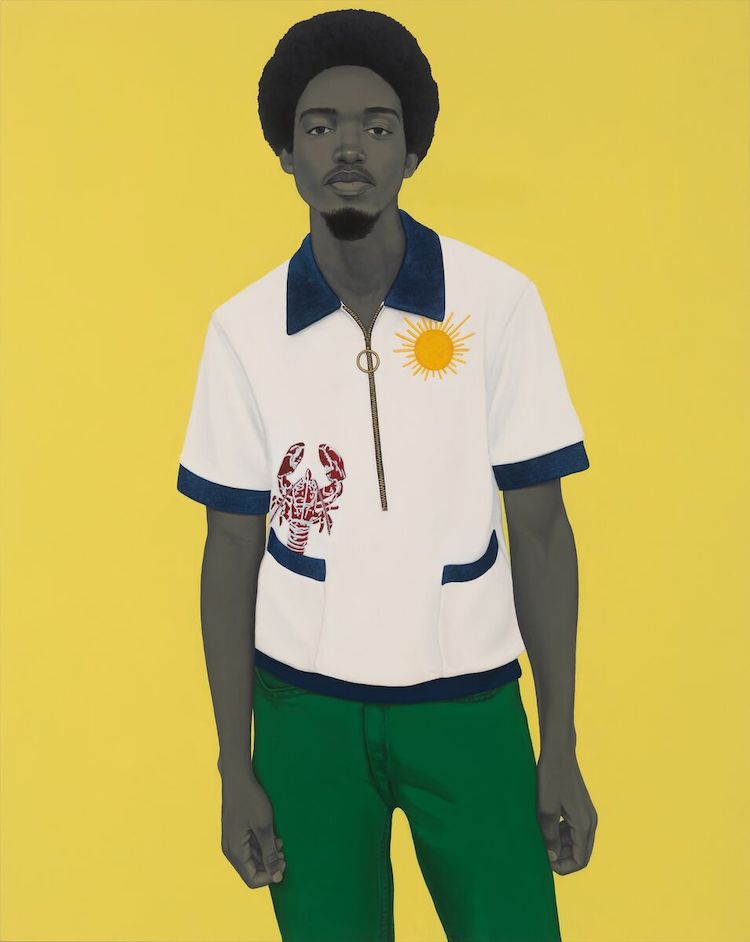

The exhibition also includes portraits of single subjects. ‘A Midsummer Afternoon Dream’ (2020) centers a woman resting on a bicycle in front of a white picket fence and a plot of sunflowers. By contrast, other single subjects in the exhibition are surrounded by monochrome swaths of vibrant color. Among these are ‘A bucket full of treasures (Papa gave me sunshine to put in my pockets…)’ (2020), depicting a man in a zippered pullover emblazoned with its own printed micro-scene, conjuring the memory of a recent beach vacation with its shining sun and lobster tucked within the pocket.