The work is immediately recognizable, be it on the bottom of a skateboard, or hanging in a gallery. Though that’s absolutely an advantage, such instant familiarity could lead you to overlook Parra's continued evolution as an artist. That defining piece, the one you could spot a mile away, is different now. Maybe it’s less articulated, a reduced definition, but much more is conveyed.

Though Parra will be the first to tell you there isn’t some over-arching meaning or metaphysical message, the composition, with its subtle structure, speaks as strongly as his signature color palette. Beyond sharing the art, my mission was to interview a friend, someone who would probably prefer not to be interviewed. That said, his very reluctance made for one of the most fruitful hours of dialogue I can remember. Hope you enjoy…

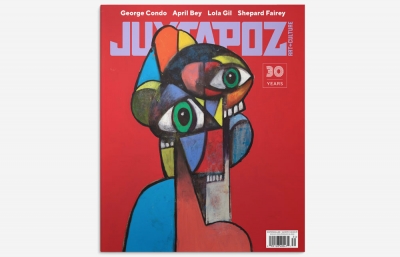

Read this interview and more in the December 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Tony Vitello: Take me through an ideal day.

Parra: That would be one in which I have to do nothing but focus on my own work. That’s a luxury, and over the last couple years, I get more and more of those days. So many things just sidetrack me, though. Maybe I’ll end up making a little logo for a friend, or end up doing something with my clothing company; things that just distract me from the artwork I want to be making. The ideal day would be waking up, having a nice breakfast, going on a bike ride, then getting home and working on my drawings and paintings. But it rarely happens, honestly.

Do you separate out your work and play days, or are you most productive when they mix together?

Basically, I just feel guilty all year round. I told my girlfriend the other day that I’ve been pretty much living a nonstop weekend for the last ten years. Meanwhile, she wakes up, goes to work, and follows that more typical routine. This nonstop weekend isn’t exactly perfect, it just keeps going. It’s like I have to do something, but I don’t have to do anything, really. All the days kinda blend into each other, which can make for the haziest state of being.

You have deadlines, be it for your clothing line, or an upcoming gallery show, but I suppose those are more long term. Anything you need to do on a daily or weekly basis?

The only thing I plan, and it’s probably the opposite of most people, is that I think, “I have to go drinking on Tuesday.” So then my Wednesday is fucked till about three o’clock. And now, being 40 years old, I have to plan these things, you know. I’m always working on something, but I have to go out of my way to plan the things I really like, which is not working. It’s going out skateboarding and, at the moment, I’m really into cycling, and going out with friends and having a few beers. Those are the things I have to plan now, which is fucking weird.

You’ve talked about guilt. Is it more often about not working on your own stuff, or guilt about feeling obligated to do something for someone else?

Definitely the latter, because you promised somebody something. I used to get myself into this problem more often because I took on other jobs, be it freelance or whatever, and I don’t have to do that anymore. Occasionally I agree to something I probably shouldn’t have, and then I end up feeling like I really have to do a good job, and will feel bad if I don’t take my time doing it right. The days go by so quick, you know?

Is cycling the next step for you after skating? Not that you’re going to quit skating, but maybe cycling is less mentally and physically humbling, and perhaps it becomes something you balance with your skating?

I don’t think so. I think it’s just because I just recently got into cycling and it’s only been a year, really. It’s new, you’re getting addicted, you become fanatical. I was skating about two times a week in our little skatepark here, outside of Amsterdam, for hours on end, so I thought that I was in shape, until I went on a bike ride with a friend. You know, just borrowed a bike, thinking it would be a mellow cruise. Turns out I was in terrible shape. So I decided I needed to do something on the side, cardio, anything that would help me maintain a normal heart rate. I think a lot of us skaters think that what we’re doing is the ultimate workout. With skating, you develop a really strong core. You’re always squatting, engaging your legs and midsection, but unless you’re pushing and pushing for hours on end, you’re not getting that cardio you need. It’s funny, though, seeing the core workouts marketed to the common person, little workouts they tell you to do on lunch breaks. We skaters don’t have to do those things. I think part of what I like about cycling is that the core is still really important, and my legs are already strong from skating.

On top of general health purposes, lots of people run or bike to achieve that runner’s high. Do your long rides help your work at all? Do they give you a sense of clarity?

You know, I used to think that runner’s high thing was kinda bullshit, but now, definitely, it’s something I look forward to after a ride. It just helps me out in a lot of ways. I don’t wanna promote cycling or whatever, because I don’t really give a shit—either you ride or you don’t—but the bike has helped me feel sane. I was going through a shitty period, dealing with a breakup, all these things, and I just needed something with no music, no stupid phone, just go out and go against the wind for two hours. I do it to clear my mind. Plus, it gets you in shape real fast.

I’m a big believer in the power of the bike too. Running hurts my knees and messes with my skating, stationary bikes are the most boring things in the fucking world. Plus, we both live in these beautiful places, you in Amsterdam, me in San Francisco.

Yeah, that’s another thing. Before the bike, unless I was skating, I would just always be in my house. I still spend a lot of time here, because I work from home, and I like it, but now I’ll be out on my bike and realize I’m two hours outside of Amsterdam, looking around, like, “Where the hell is this? This is sick!”

Last week, riding my bike, I ended up on a street near Sutro Tower where I’d never been in my life. I thought I’d seen every nook and alley of SF, but the bike took me somewhere I would have never gone on foot, car, or skateboard. It was awesome. I just stood there and took it in.

Unless you’re 80 years old and have a nice, vintage car, and it’s a Sunday, you’re usually just using the vehicle to go from A to B. On the bike, you’re going from A back to A, and zigzagging around along the way. For me, I was down in the dumps, and the bike brought me out of it. Plus, you start to get good at it, but not super quick, kinda like skating. In the beginning, you suck—on the road getting passed by dudes in full lycra suits, and you’re thinking to yourself, “Fuck them,” because you have that skateboard mentality. I was literally out there in my Thrasher hoodie and Air Max shoes, like “Fuck it.” Then, six months later, I’m that guy in the lycra suit.

Haha! Yep, the sausage suit. That’s what I like to call it. My father was really into cycling, and his dad actually raced back in Argentina. We’d go out and he was always looking back shouting, “You should be one inch behind me!” I would laugh, like, I thought we were just cruising, why do we have to be drafting right now?

Yeah, dude. I have my girlfriend draft all the time, even just this morning, I’m looking back at her, yelling “closer to the wheel!” Skateboarding, as you get older, it makes you sort of autistic to the rest of the world. You’re in this little group with your small circle of friends, and you learn from that world that basically everything other than skateboarding is whack. I still have that mentality. And I kinda love it. On the other hand, with cycling for instance, I meet all these new people. Maybe you’re going the same speed, you catch their wheel, they catch yours, and you learn a little about them. It’s not like I’m going out to dinner with these dudes, but it gets me a little out of my skateboarding bubble.

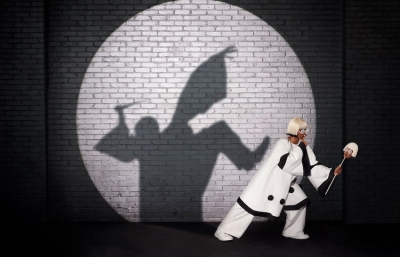

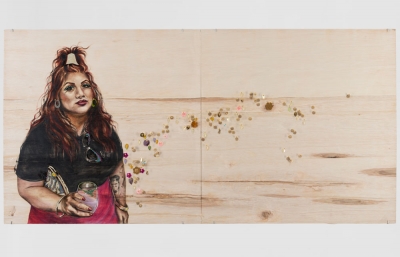

Photo of Parra by Tony Vitello

Plus, as you get older, a bunch of your friends quit skating, and then you have to relate to that skateboarding mentality with 16-year-old kids.

I look at these kids and I think, “I’m so glad I don’t have to do all that again.” Sometimes I’m jealous of how long they can skate. I’m not even upset about their abilities. The progression is one of the coolest things about skating. But yeah, I’ll get jealous for a second, and then I’m like, “Imagine having to go to school today.” I didn’t really pay attention in school, and didn’t follow through with the art school thing either, but nowadays you can almost school yourself. Everything is just available to you—online classes, workshops, how-to videos, and it wasn’t back then. If I had to do school nowadays, with this generation, the phones and computers and stuff... I don’t know if I could do that.

Have you walked by a classroom nowadays? It’s a bunch of kids on their laptops and phones. How do they stay focused with all the random websites and portals you can find? I don’t know how a teacher handles that.

Can you imagine? Either the kids are just fucking off on their computer or they’re looking up what the teacher is saying and checking if it’s right or wrong. The teacher probably just wants to kill the kids. I guess this is also a good way for us to get into the art talk. I think I never really understood what art was until I did it and realized that there are no rules. That’s possibly the weirdest thing about what I do.

Perfect, because my next question was going to be about your art, since you just mentioned progression in skateboarding. I want to know about your progression as an artist. Has it been gradual? Have you suddenly started to feel more comfortable?

It’s been more recent. You know me, though. I’ve been very uncomfortable through this whole ride. I think part of it is that there are no set rules or guidelines—like every five years your style needs to change, or whatever. It just doesn’t work that way. You’re literally there with a blank canvas, like, “How’s this gonna work?” And for me, since I didn’t do the art school thing, the first thing I really needed, speaking of progression, was to get familiar with graphic design. There are rules with type and such, and when I started my internship, I thought, “Hey, I know about this stuff from skating.” This was around the time I was kinda bumming out on skating because I wanted to become a pro skater and I didn’t “make it.” So, instead, I started studying all the way back into the magazines from the ’80s. I studied the graphics, and saw that most of the stuff was hand done. So here I am, probably 1998, with better computers and technology than the ’80s, but I really liked that hand-drawn DIY style. That was my first lesson, this collision of worlds. You had graphic design with its rules, and then you had skating with the whole attitude of “fuck rules” and everyone telling you what to do. So I just started to hand draw all my own letters. At the time, I wasn’t thinking that this was something that had already been done like 15 million times already. I had no clue. I was just going off the skating shit. I was into hip hop and skating, that was my filter. But going back to the progression, not having anybody telling you what to do is definitely a cool thing, but it also makes things difficult.

Do you ever worry about developing so much to the point where people don’t recognize your work?

It can definitely happen, especially to high-end artists who do something different every time they have a new show. For me, getting known for a specific thing, you don’t want to deviate from that too much, so you end up creating these stupid little rules for yourself. It took me so long to break some of my own rules. So I can only admire the people that try and do something totally different, the ones that just say fuck it and go a whole other direction. My father did that sometimes. He’s a painter as well, and would occasionally just flip it and go into a totally different direction, not even thinking it through. I couldn’t do something like that.

What was the hardest rule for you to break of the ones you made for yourself?

The hardest thing was to let go of some of the humor in my work. I wouldn’t consider myself humorous, per se, but some of my early work was more tongue-in-cheek. I would include more text in my work to convey that humor. But at some point, I started to get upset and think to myself, “this isn’t funny.” You look at it five times, and it’s just boring. So I actually think, as a byproduct of the humor, stopping the use of text in my work was the toughest thing to break, dropping the typography from the painting.

So the challenge became how to convey something without saying it?

Exactly. If you include the text, you give the answer outright. It also makes it very comic-like, which is obviously a style I like, but becomes you telling the viewer how to look at it, and telling them exactly what you mean. When I stripped the text, I started to notice that some of the work wasn’t as good, and started to take more time on my projects, and really focus more on my composition.

I use humor all the time, including moments that are uncomfortable or where I’m unsure about what I’m saying; humor allows me to kinda dismiss the seriousness or just laugh things off. Was it protecting you?

Definitely. It was a total shield for me too. But over time, you do things long enough and become a bit more secure about your own stuff. Now I’m at the point where I like my drawings more, and I don’t have to come out and explain that it’s funny, or maybe I just grew into it.

Portrait of Parra by Damon Way

I feel like, as skateboarders, we have this viewpoint where we see the world differently, and other people don’t get things the way we do. It’s something I’m proud of, but sometimes, when I find myself in real world situations with a suit and tie, talking to people about their world, the normal world, I start to feel this insecurity creeping in. Did you feel that way at all as an artist coming from the skateboard world?

Yeah, when I started in the graphic design world, I immediately had this impression that these people were super serious, and I would find myself feeling insecure and changing my work before they could even say something. I would insert that humor and find a way to laugh it off. But it wasn’t wasted, it was just part of the learning process, to finally arrive at the point where you can tell yourself, “Hey, I like this. I’m going to stay with this for a while.” I’ve gotten to this more comfortable level of security with my own work.

You’ve been doing a lot with sculpture the last few years. What does that 3D world provide that the 2D canvas does not?

That’s a really good question, and I never really thought about sculpture until I met Mathieu, a Belgian guy who runs Case Studyo. About ten years ago, we started by doing these sticker packs and posters. He also had a store, and wanted to do more projects, and suggested doing a toy figurine. At first I was hesitant, like, “I don’t know, I’m not really into toys”. But he pushed it and said he could do something in porcelain, which sounded cool. So we started with that, and ever since then, he's been my guy for the 3D stuff. I think in 2D terms, and can’t really draw 3D very well, so I need a partner, and I like that. It’s really cool to collaborate to bring one of my characters to life in 3D form. It’s been addictive.

So, in the 2D world, you wouldn’t invite someone onto your canvas to help you out, but the sculpture stuff allows you to collaborate and gain expertise from another field?

Exactly. I definitely admire artists who do the whole process themselves, but for me, I need it to look perfect. I have the vision in my head, and that goes from the canvas, to a T-shirt, to even a little skateboard wheel graphic. I need that composition to be perfect. I tried to work with clay and 3D programs, but those things aren’t easy and it would take at least five years to get good.

You invite someone in, bring your expertise, they bring theirs…

Yeah, a good friend and himself a famous artist once told me, “Collaborate if the other person is bringing to the table a skill that you don’t have or a material that you can’t use.” That’s when it becomes an addition, and a true collaborative effort. I take that same idea back to clothing. If you’re a T-shirt brand, why would you collaborate with another T-shirt brand? I mean, you can blend two famous names together, that can be cool, but what’s really sick is working with a guy who’s sculpted marble for the last 50 years. That’s going to be something really cool. It’s really fucking sick to see something that you drew evolve into this life-size form. I’ve got some new things in the works. The big plan in the coming years is to make public sculptures.

I’ve seen your signage and characters in Amsterdam. Does seeing your work, life-size, biking through a public park in Holland, bring you the most personal satisfaction?

Definitely. That is one of my dreams, to see one of my characters, a huge red sculpture, shining in the middle of a beautiful green field. That would be amazing. I think part of what you’re getting at is the acceptance from the average Joe. Galleries are a safe place for an artist, but when you take your work out into the public, to the person that isn’t necessarily a fan already, and they look at something you made, and they think it’s sick, that’s a big win. I had that happen in Rotterdam. My work was out there in the public, and I got so much more feedback from random people that knew nothing about me. It was great! Funny, because in skateboarding, you could show a regular Joe an Ollie down a 12-stair, and kickflip down, and they probably wouldn’t know the difference—they’d just think you did a somersault or something. Those different trick variations are something that only people within the world of skateboarding will really understand. With art, you’re able to reach more people.

To a certain extent, everyone desires the acceptance of their peers. It’s more important to some than others, but if you can reach a larger audience without sacrificing what you do and how you do it, then that’s awesome. With your dad being an artist, what did you learn from him, and are you close?

My parents had me when they were both relatively young, about 24 years old. They didn’t really last too long, and my mom left and I have no idea where she went. My dad raised me the first few years on his own, and then met someone who became my stepmom, and I consider her my mom. That’s the quick backstory. My dad was already an artist when he was young, doing shows, stuff like that. He was definitely his own person, almost like a cult figure. We moved around a lot—me, my dad, stepmom and stepsister. My dad was always that weird, cool guy in whatever small village we lived in, and he’s still that guy. I admire that, and I think that’s why he really encouraged me with skateboarding, because it was something different. I kinda got into art later in life. We were closest was when I was really young, that age where everything your dad does is fucking rad. We talk on the phone at least every week for like, an hour. Sometimes I’ll call him when I’m struggling and say something like, “I hate this painting! I want to burn it!” and he’ll be like, “What are you waiting for? Fucking burn it!”

So he’s not the guy who’s gonna talk you through fixing the painting, or tell you it’s amazing to make you feel better?

No. If he thinks it sucks, he’ll tell you. I’ve seen him do these things himself, like kick paintings into the dust in the backyard when I was younger. He would hate some of his own stuff. But it’s been great over the last five or six years, as I’ve gotten more serious about painting, because he’s lived this life already. It’s perfect. He’s a good mentor. But he’s also your dad, so sometimes you just don’t listen.

What is it that makes you hate a painting? Is it that you end up spending too much time with it? Do you have a message you’re trying to get across that isn’t working? Or is it as simple as having an image in your head of what it was supposed to be, and it didn’t turn out?

It’s really the simple version you just said. Often, when I’m done, and something is hanging at a gallery or printed on a T-shirt, you look at it and you’re like, “Goddamn it, I didn’t even really finish that.” The subject should have been like five centimeters to the right, or this should have been over there, etc. For me, it’s all composition. As I’m working, every day is different, and when I’m stressed, I feel like I rush to finish. I can look at stuff from ten years ago and remember that it was a shit day for me, and it shows up in the littlest details. What I try to convey in paintings is really not that deep. I’m just trying to create a nice composition. I hate to tie everything back to skating, but that’s really the common thread. Since we were young, as skateboarders, the only thing that really matters is whether or not something is cool.

Is there an ideal start-to-finish time for a painting or a gallery showing?

I mean, it’s all in your head. Too little time feels like you’re rushing, but if you spend too much time on something, you get stuck. Personally, for a gallery showing, I try to give myself six months. Doing twelve pieces gives you about two weeks per painting, which you would think is plenty, but sometimes you fuck up, don’t track your time well, and end up having to make six paintings in a month to catch up. Other times, you just get in the flow and it’s easier. But there are bad days, dude, a lot of bad days. Those super good days don’t usually come one after the other. Honestly, what really helped me, and I don’t mean to promote Apple as a company, was when they put out that iPad Pro thing with the pen. I’m not really big on technology, but out comes this Apple thing and I try it, and it’s super sick. I always start with pen on paper for that initial sketch, all scribbly or whatever, and then I’ll just copy it into the iPad and start tracing for days on end. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. It starts with a weird scribbly drawing, then after a couple days, or maybe a week, I get it how I want it. In the past, that whole process would be like 60 scattered pieces of paper. Now it’s all neat, in one little file, and that allows for more space in my head. It’s really just a piece of paper, but it’s in the device as opposed to all over my floor.

Ok, now we’re gonna get into the existential part. I know you don’t really like doing interviews, and you just said that there isn’t necessarily deep meaning or messages in your work, but do you want people to know who you are at all?

Why would I want them to know about me? I just want to be judged on the merit of my work. At an art show, most people don’t even know how I look. Sometimes I stand next to people in the gallery and listen to them talking about the piece. They don’t even know that I made it. I try to not have my picture taken, but that’s hard nowadays. I don’t know, it’s not like a street artist thing, but I’ve always just thought, like, why the fuck does what I look like have to do with anything? I don’t know why that’s interesting.

When I was younger, I read a bunch of Ansel Adams books, and to this day, I can’t tell you a lot about him personally. I can recite techniques, and his studies on the nature of light, though, and it really stuck with me, even changed how I viewed the world.

Those things are very insightful. Truth is in the process. Even with skateboarding, I always loved those Trick Tip videos where the guy explains how to Nollieflip or whatever. I still do. Me and my buddy Eelco do it to each other all the time, giving each other the rundown on how to make a certain trick. It’s all about technique. I don’t give a fuck about what kind of food people are eating or what jeans they wear. That’s the type of information that just clutters up modern life. I’d rather kids be asking how to do a Nollieflip noseslide, as opposed to asking where to get a certain colorway of Janoski shoes.

I agree. There can be useless information overkill.

I mean, it’s not like we didn’t care about style or dressing a certain way in the ’90s skate scene, but it wasn’t so shoved down your throat back then. I don’t want to give people information about my lifestyle and be judged on that when it has nothing to do with my technique or the art that I make. Funny, visiting my parents, they were all complaining about their computer. It’s like they know about the internet, but they don’t really know what it is. I dig those old people that just don’t give a shit about it and don’t even care to learn.

Wouldn’t it be nice to adopt that mentality, and not feel the need to stare at your phone and mindlessly scroll through social media?

It’s over for us! A few years ago I bought my parents a cell phone and laptop because they were about to go on a long trip, so I wanted to make sure I could reach them, and vice versa. So I set my dad up with the computer and he’s just like, “I don’t get it. I don’t care.” I pulled up YouTube and he was just like, “What do you even look for?” So I just typed in Picasso because I know he’d be into that, and then boom, in ten seconds he’s watching a sick documentary on Picasso. You could kinda see that lightbulb going off, like he understood the power, but at the same time, if an ad pops up on screen, he doesn’t know what to do and clicks on it. Then he’s on some random site and doesn’t know how to get back to where he wants to be.

Lastly, you mostly draw women, rarely men. Have you thought much about why?

I think it’s because women are the creatures I’m least familiar with. I’ve been in relationships with them my whole life, but they’re still like these mythical creatures. If I were to just draw a dude, I’d just keep looking at them thinking, “Oh, this looks like Benny, this looks like Tony, that guy looks like Eelco.” There are too many references. And that kinda answers the question I get about why I always draw beaks and birds. I think I just don’t want the characters to look like anybody in particular. In my new work, my upcoming show, there are no faces. The face is always concealed, and I like that mystery. If there’s anything anybody takes from my work, any meaning, it’s hidden there in that strange, mysterious moment.

So, basically, just no faces. Not yours, not anybody’s. Maybe we shouldn’t include this in the interview, now we’re just talking shit.

No, include that. This is like a shrink session.

We’d all be better off without faces, like we’d still be able to see, but we wouldn’t have a face.

When I was a kid, I always thought ears were weird, the way they came out of your head. I still think they’re bizarre.

Parra will be featured in Juxtapoz x Superflat at Vancouver Art Gallery, November 5, 2016–February 5, 2017. He also opens a solo show at Joshua Liner Gallery in NYC on

November 17, 2016.

----

Originally published in the December 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.