Before discovering a SodaStream that conveniently turns plain H2O from the tap into delicious, sparkling water, Josh Reames didn’t consume water at all. At least that’s what he told me. How his body survived such dehydration all those years before his current fizzy infusion is up for question, but he seems to have survived and thrived.

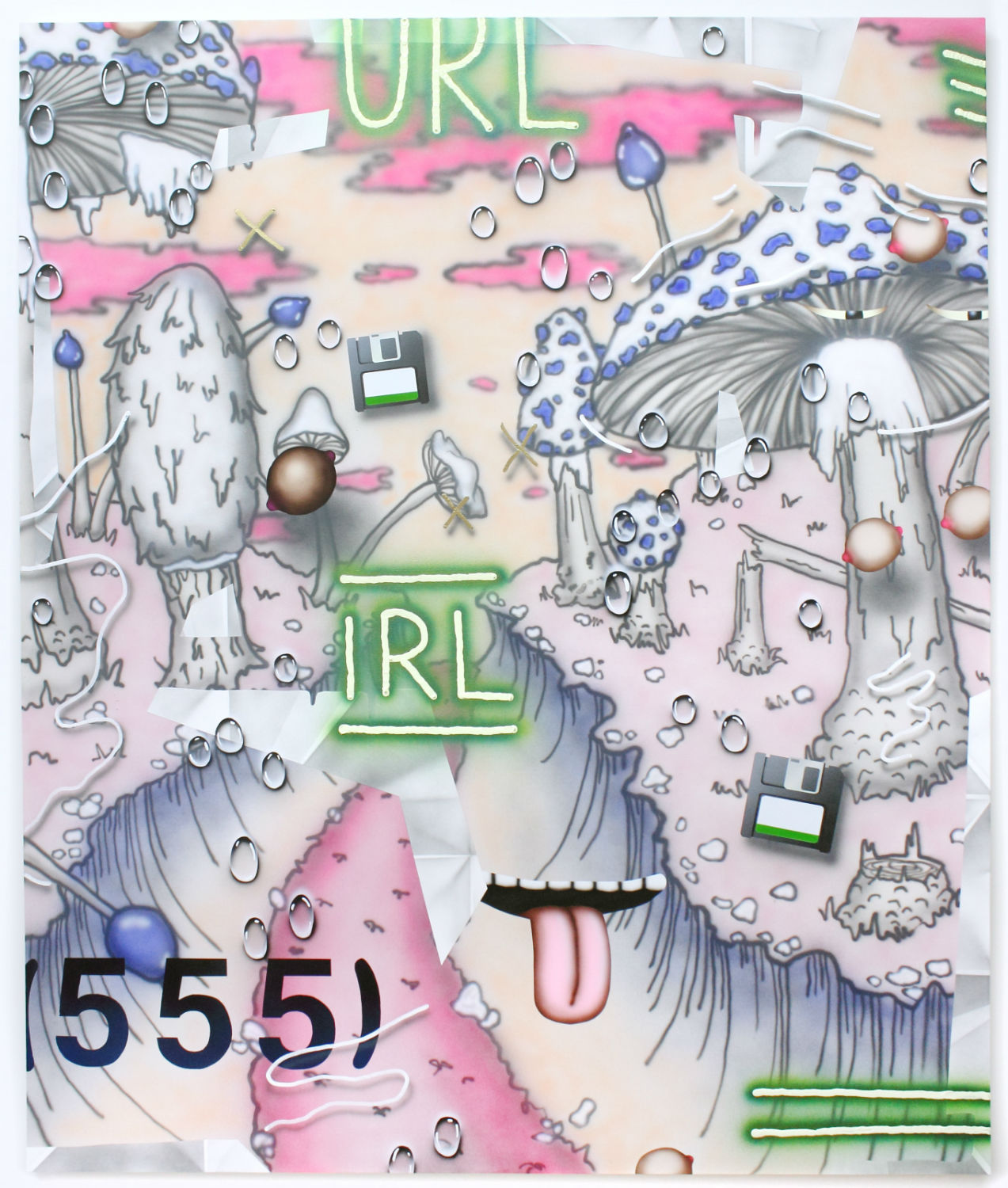

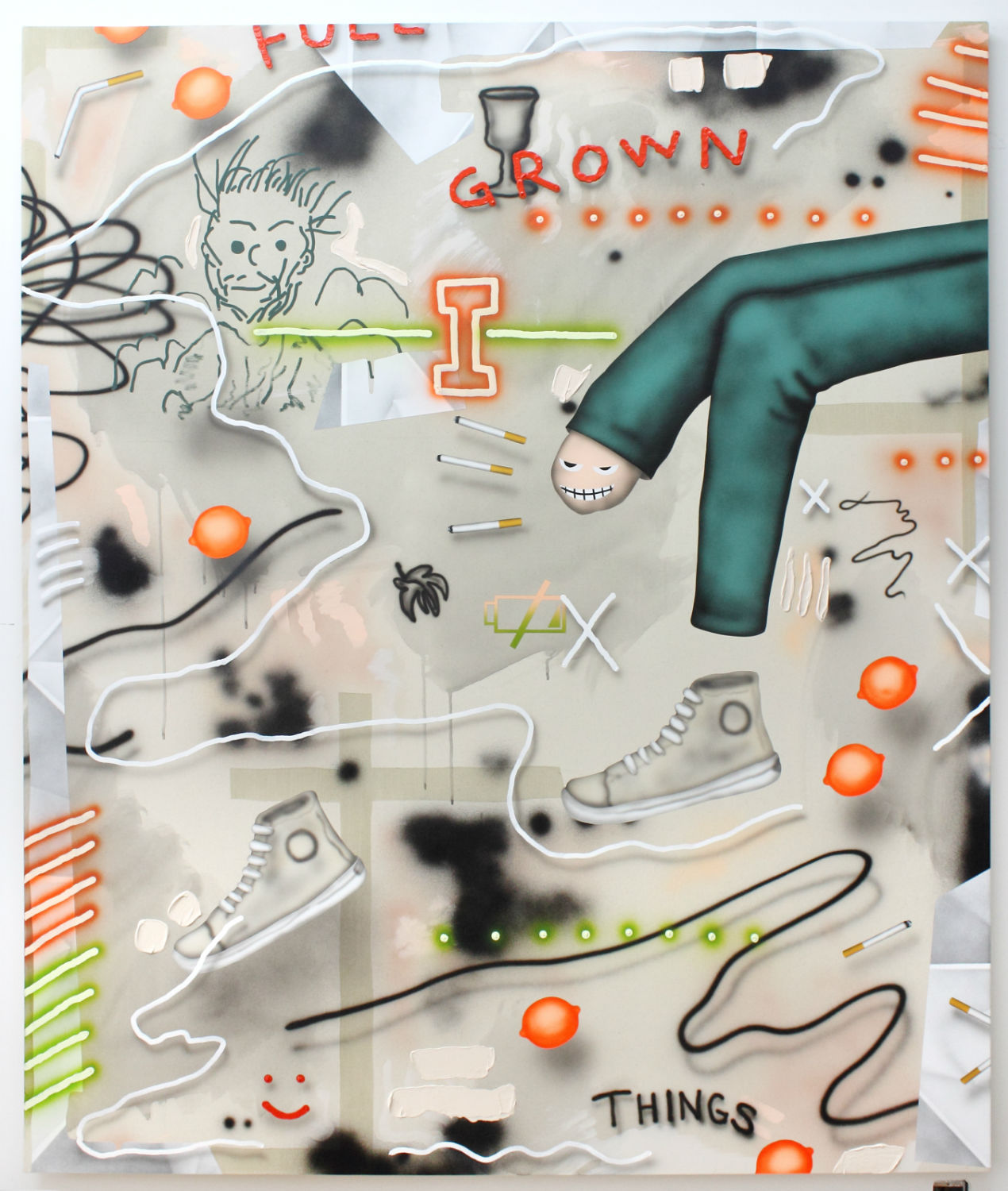

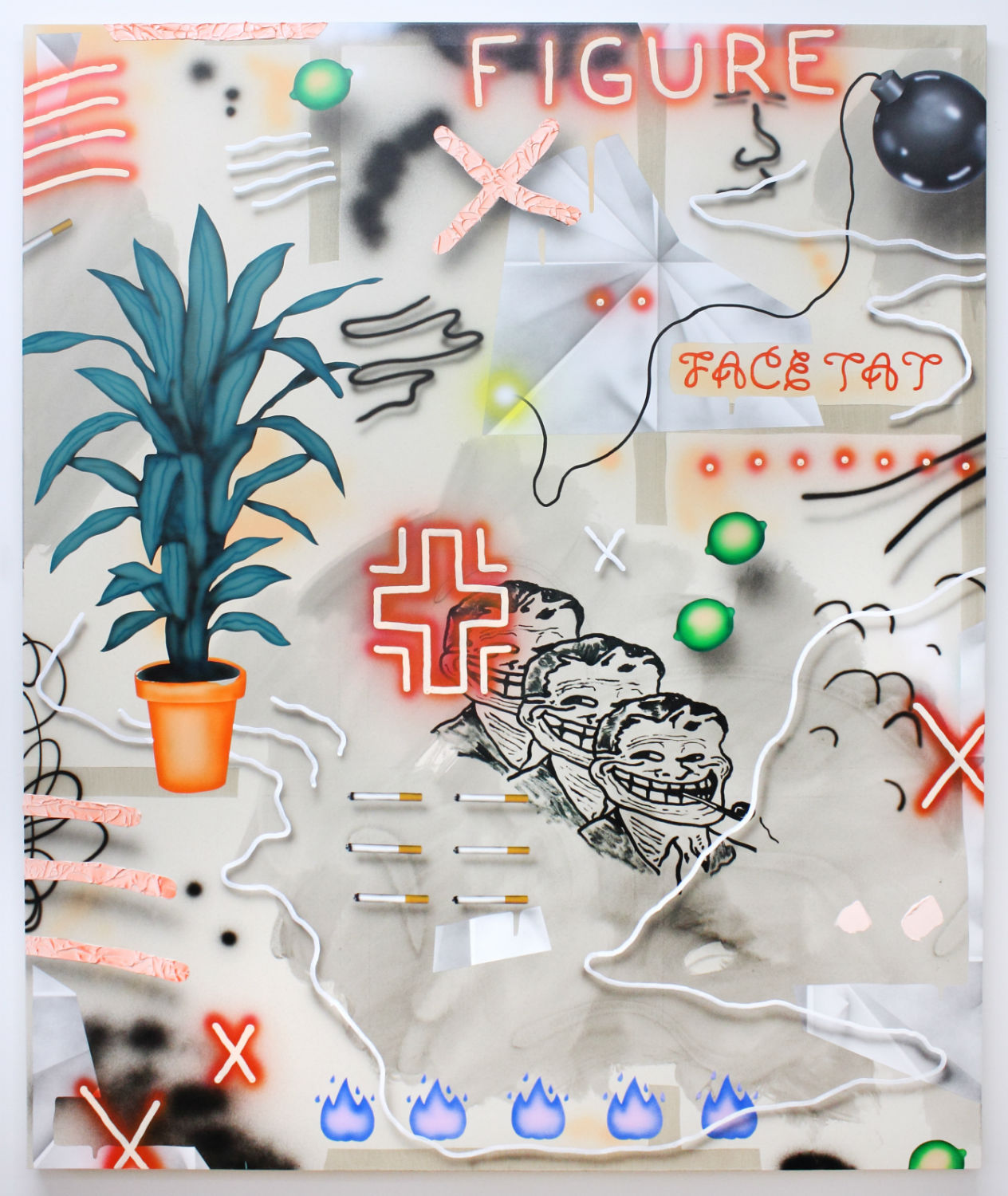

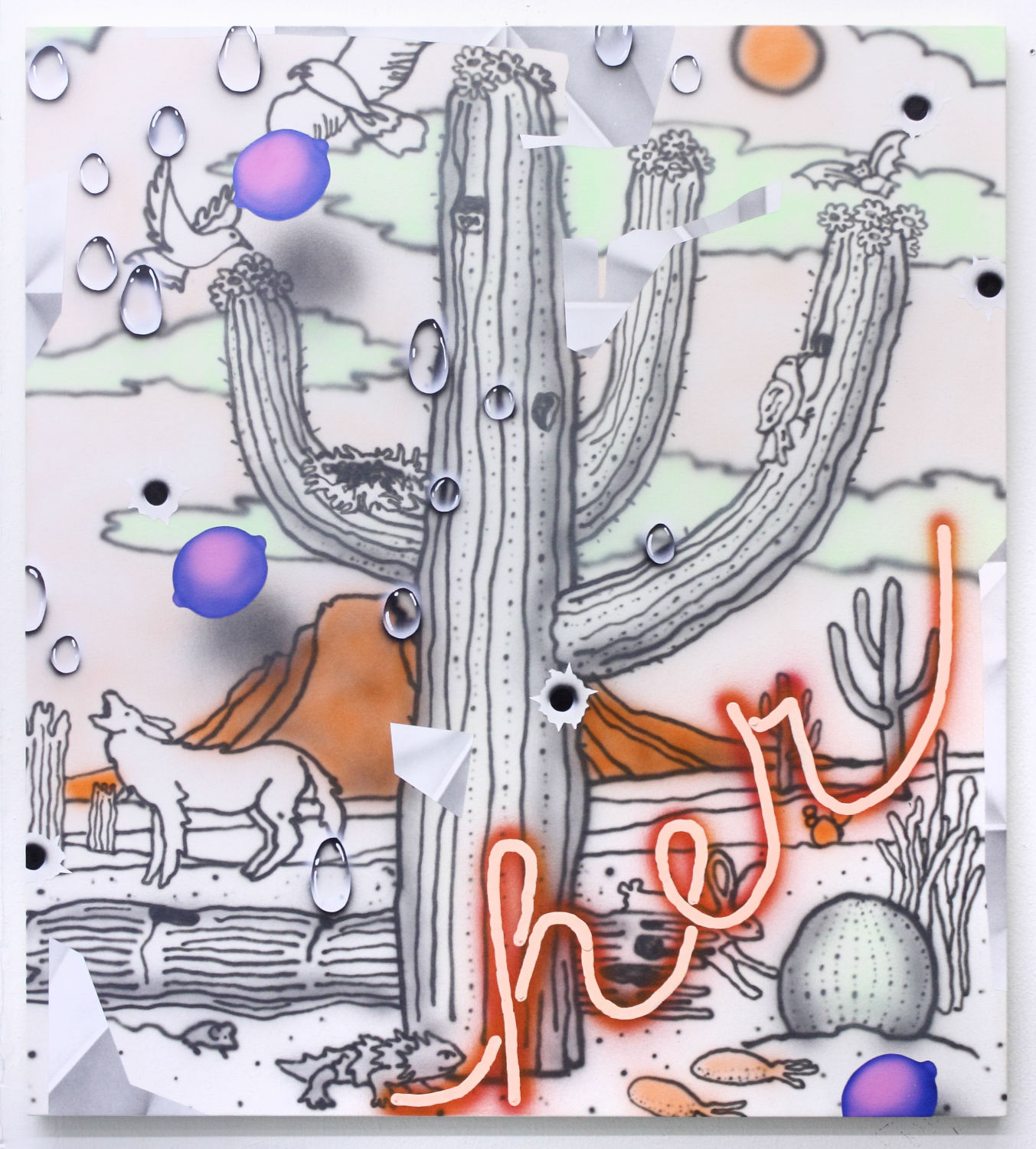

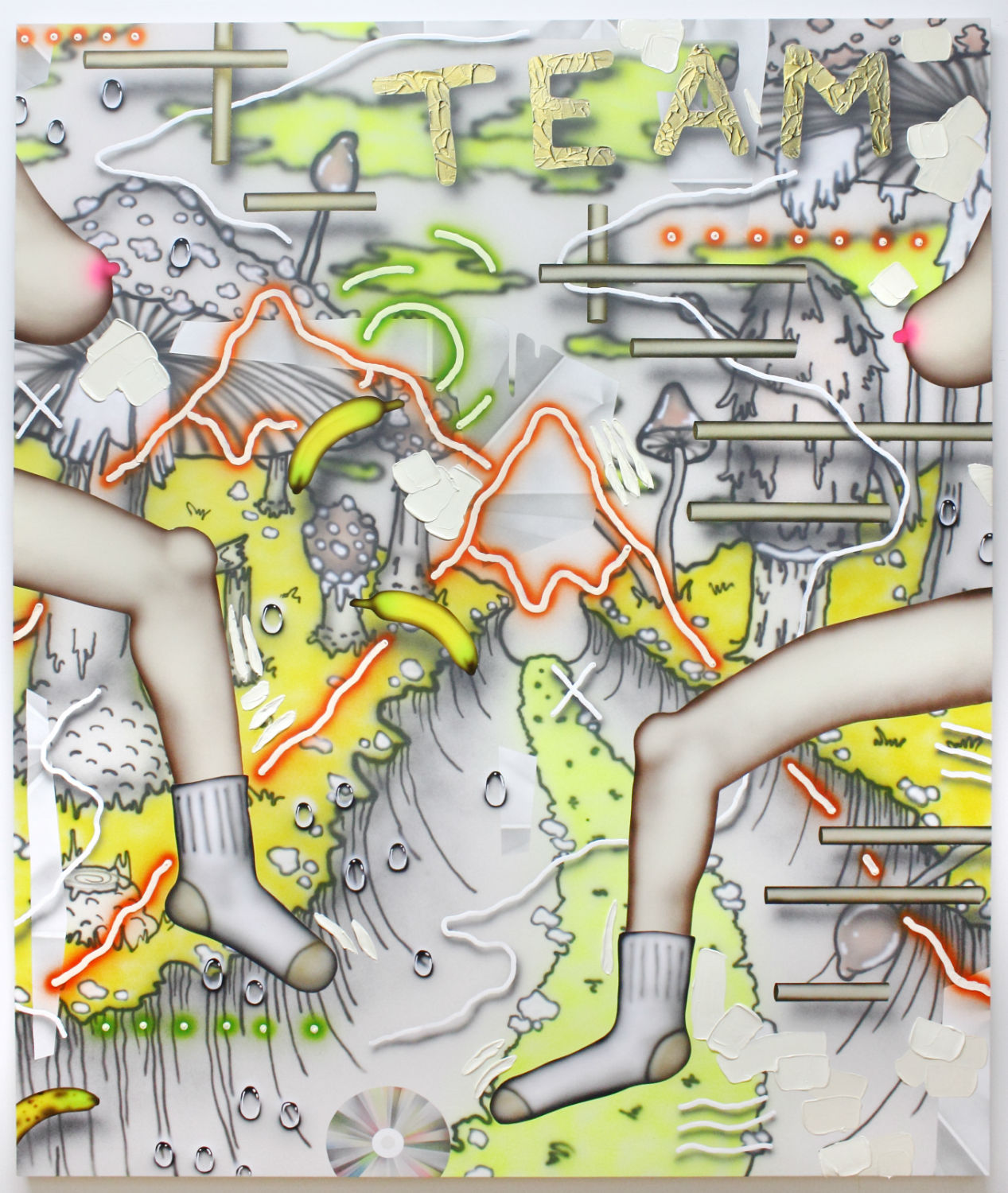

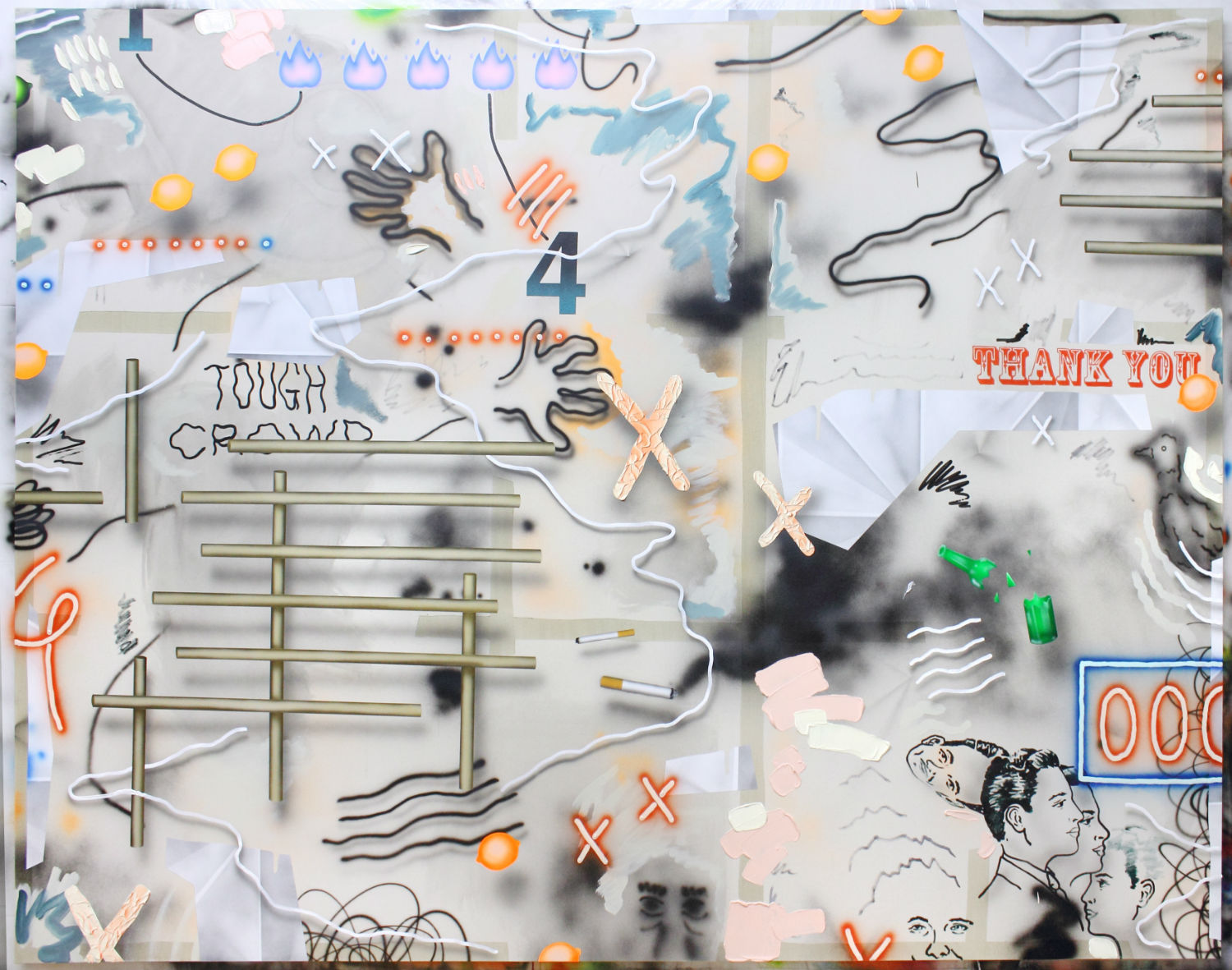

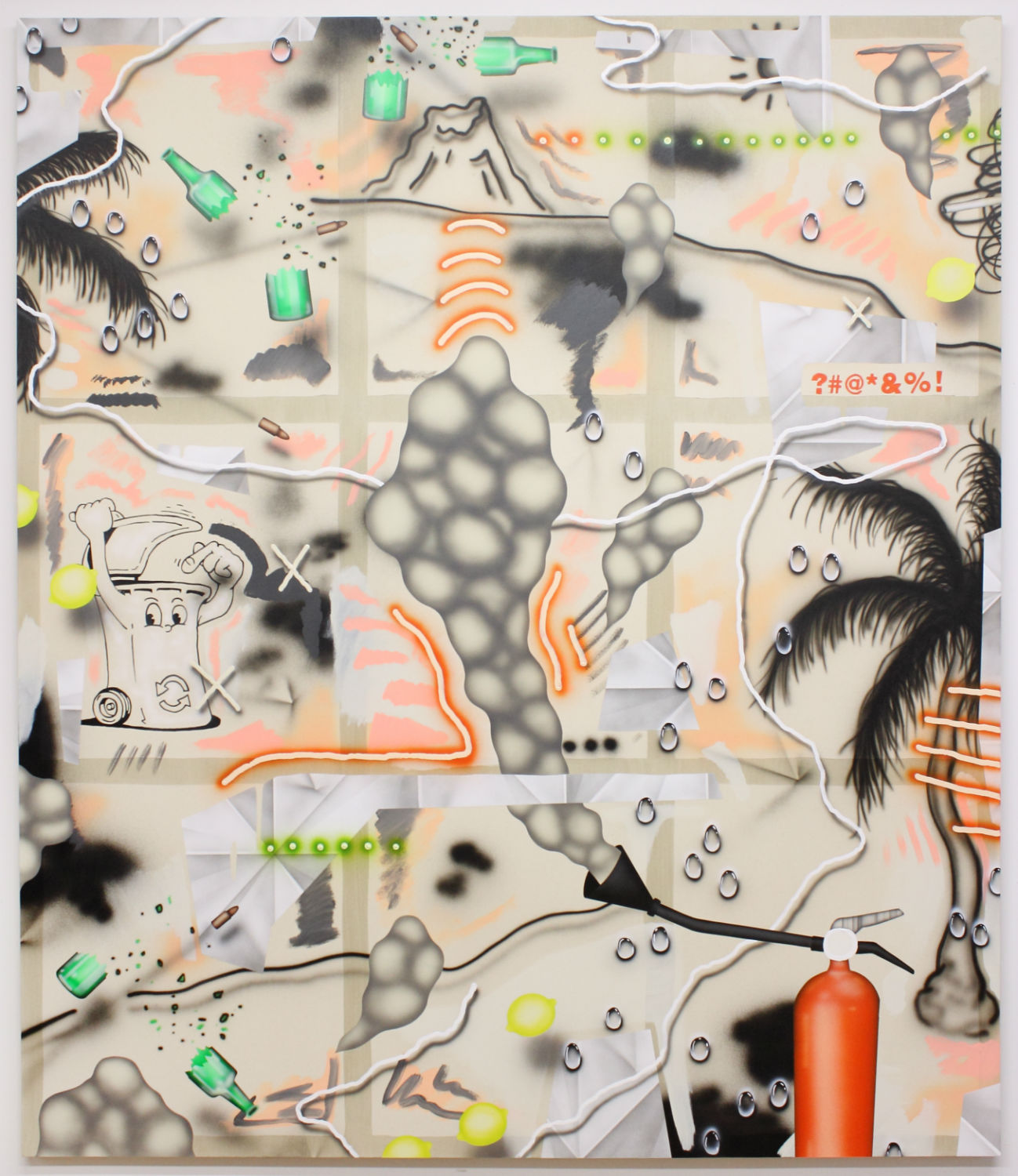

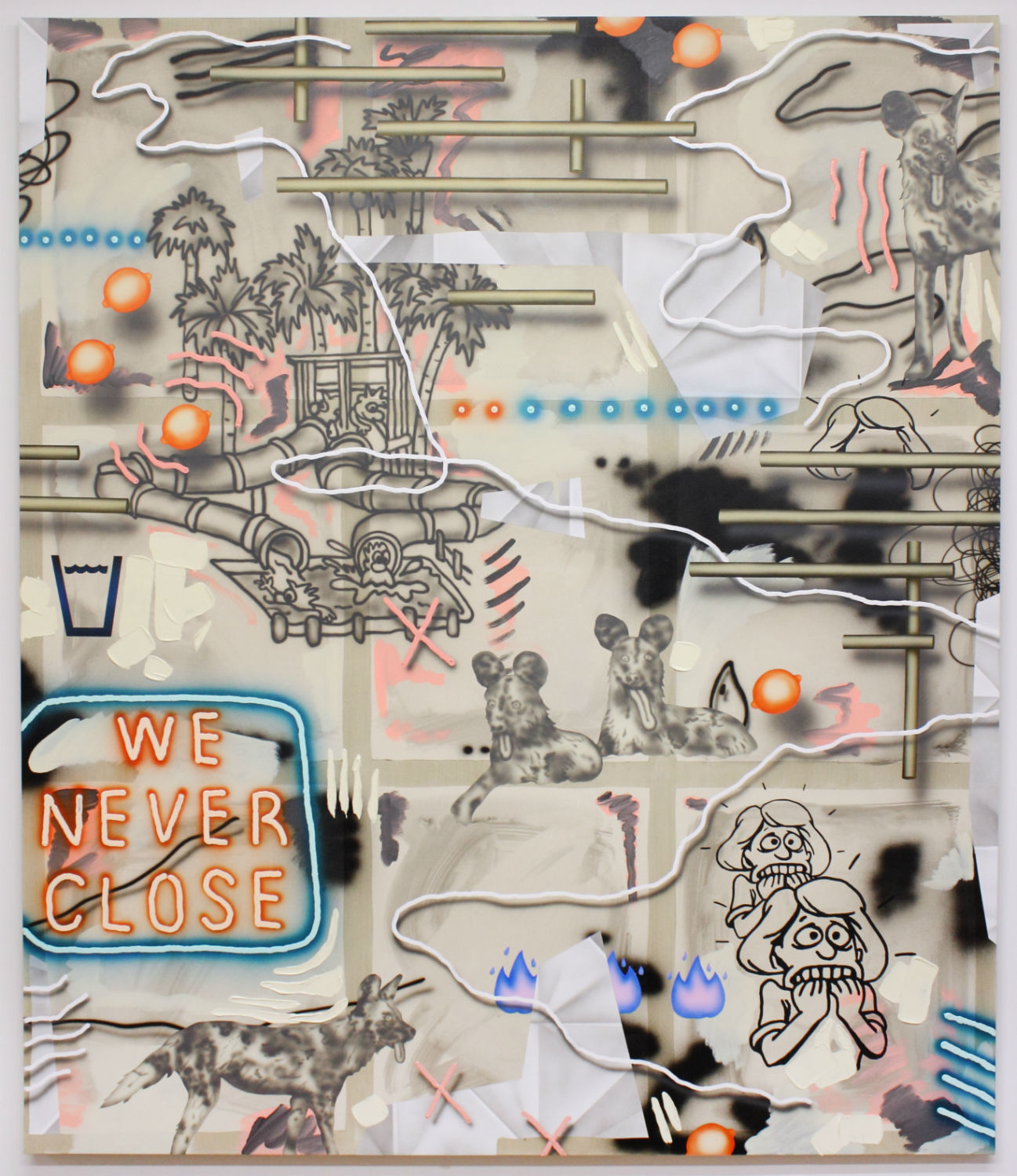

Born in Dallas, educated in Chicago, and now residing in Brooklyn, Josh has garnered the interest of galleries and collectors at a brisk pace. His studio exists in an unassuming building in a residential area of Bushwick, amid a dense, Puerto Rican enclave. Mediocre street art murals are still minimal, and amenities like artisanal coffee shops, brunch spots and five-dollar scoops of ice cream have not arrived—yet. His work addresses a multitude of ideas by employing emojis, text, geometric shapes and patterns, symbols, common objects, plants and the occasional palm tree to construct a visual dialect on large canvases. Appearing in several group shows around New York over the last few years, Josh’s paintings have become instantly distinguishable and engage a wide audience. Described as paintings that couldn’t have been imagined before digital imaging, their appeal to our current image-searching and scrolling-obsessed culture couldn’t be more opportune.

This is an excerpt from the June, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our webstore.

Austin McManus: You started painting right around the time when the Internet and social media, which you admit are integral to your work, became ubiquitous in our culture. Can you explain how our current use of technology informs some of your ideas?

Josh Reames: I think the biggest influence of technology is the never-ending flow of images and information. The infinite blogrolls and Google image searches and Wikipedia binges have fundamentally changed the way we consume information. Often, when I start researching something, I find that I'll end up reading about things that have nothing to do with what I originally started with, something I'm sure most people with the Internet do. I tend to make paintings like that.

I‘m fascinated by how emojis have quickly become a new universal language in our culture. The first time I sent them to my mom, she had no idea what they were, and freaked out in a good way. Now, in just a few years, they have assimilated into everyday global communication, and she uses them regularly. Since you incorporate a number of emojis into your paintings, I’m curious about their role in your work.

It's modern-day hieroglyphics. Emojis operate in my paintings like any other object, number or image—they're all signifiers being spilled into the picture frame. My imagery and content comes from what’s around me, and that includes emojis. I don't think of them as being more or less important than any other image or brushmark in a painting. All of these things are objects being depicted in various ways.

The other day, we briefly talked about being inundated with so many images now, and often unknowingly referencing other art or ideas. Do you think, at this point in time, that this is somewhat unavoidable, short of turning off all glowing screens and alienating yourself from contemporary culture?

Yeah, I think it is mostly unavoidable. I just don't think it matters when artists sometimes refer to other imagery and other artists. The first artist likely didn't "own" that imagery anyway. We're all looking at the same shit. It's the problem with these "who wore it better" websites; it doesn't take context into consideration. If you look at a three-inch image of two different artists, it shouldn't be too difficult to draw some comparisons, but why? How is that useful? I don't think the answer is to turn off all electronics. I think it's better to be aware of what’s around you, but I also think it's time to get over the idea of owning images.

In the past, you used the word “escapism” to loosely describe what your work tends to address. I’ve always loved the sound of that word and its meaning.

I spent a few years using a lot of vacation and tropical imagery. I was interested in the kind of slippage between an idealized version of something and the reality of it. Vacations are a good example; it's this hyper-idealized thing, but the actual experience is often quite different. I always think about the Corona commercials with the people sitting in the beach chairs with their Coronas—the perfect place with a perfect beverage. But Corona sucks, and those people are probably getting sunburned and sand in their underwear. I guess that's what escapism is, though, the idea of something better.

----

Read the full interview in the magazine! Subscribe and save 60% off the newsstand price.