Genevieve Gaignard

A Hit to the Head

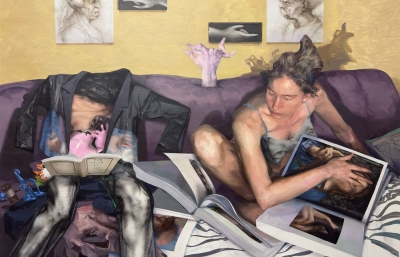

Interview by Shaquille Heath // Portrait by Charlsie Gorski

I’ve seen many artists whose artistic ventures employ beauty to entice the viewer. Genevieve Gaignard’s work is probably my favorite. A delightful multimedia artist who creates photographs, installations, collages, and other mediums, her artwork tells the story of America’s history of color blindness, and its eager violence upon Black people, women, and everything in between. Pretty pinks and bushy hairdos, florals, and red-lined lips cleverly conspire together, deconstructing the intricacies of race and cultural identity.

Understanding that white supremacy runs rampant in the darkness, Gaignard’s artistic pursuits are there to shine that light—to help you see. Gaignard shared with me that the level of visual acuity runs the spectrum, and this fact kind of boggled my mind. As a mixed Black child who never had a Black baby doll, how can I not see a work such as "Black is Beautiful'' featuring numerous of these dolls all together on a bed, and know its meaning like it's been written with a sharpie on the wall? I can’t comprehend how you could look upon a photograph of Gaignard herself (who often utilizes her own image to play into stereotypes), wearing an Antebellum dress with thick coarse hair, and not think about the histories she’s clueing into. Her work is a reminder that race is entrenched in everything we do. It is in everything that we have. No house was built without wood from its trees.

And yet, I’m sitting here after the disastrous Supreme Court rulings on this discontinuation of affirmative action and abhorrent LGBTQ+ discrimination, and all that I want to do is project Gaignard’s work into the sky. In this interview, she tells me, “Beauty seems fleeting and the underbelly of the work is not. I don’t know if it’s necessary for the message to always hit you over the head, yet if one feels compelled to spend a little more time with the work, the veil of beauty starts to dissolve.” But I disagree. It’s obviously a needed bonk to the skull. And all I can wish now, with a stiff hand on your noggin, is for the power of Gaignard to compel you fully.

Shaquille Heath: I’m so excited to share words with you! How are you taking care of yourself right now, and where are you finding your joy?

Genevieve Gaignard: I’m currently an artist in residence at the Lunder Institute for American Art in Waterville, Maine, thanks to Director Erica Wall. Summers in Maine are gorgeous. I am happy to be here with fellow artists and immerse myself in my studio practice. I am feeling grateful to be able to connect with everyone here. It’s refreshing to have the freedom to challenge myself in the studio unprompted. During my time here I am trying to tap into moments of joy. Sometimes it looks like singing along to music in the studio or going to a baseball game with friends, learning how to play Spades, and accepting the present moment.

Congratulations! That sounds so lovely. I'd love to jump back to the very beginning. Where did your practice begin? Did you always know you wanted to be an artist or was there an origin story?

My journey began in childhood where I nourished a love for self-expression on the walls of my bedroom, which I always attributed to being an angsty teen growing up in the ’80s & ’90s… I don’t know if you remember Kat’s bedroom in 10 Things I Hate About You but there's a scene where she’s laying on her bed and the wall is covered in posters, snapshots, and ticket stubs. If you look close enough in the corner, you’ll see a sliver of pinkish floral wallpaper behind the posters—that was me. I loved ripping out images from magazines and collecting band and movie posters. Those years were so formative to my expression and I didn’t piece that together until after grad school. I was always creative, but I didn’t really know I could be a serious artist. I grew up in a small town in Massachusetts and pursued a degree in pastry right out of high school. I’ve been fortunate to cross paths with the right people in moments of my life when I’ve needed guidance most. A former professor of mine offered me a piece of advice and told me to go after an art degree. I listened and never looked back.

Well, we thank that professor for their smart advice. Within your art, your identity molds and shifts into different portraits. There always seems to be a new story. Do you discover new things about yourself when you stretch your persona in new and different ways?

When I’m creating a character for a photograph, it’s a very focused process. It can seem like I am “stretching” my persona, but I view the characters as a cast of societal stereotypes. I think the images make it easy for viewers to believe these characters are solely facets of who I am specifically, but that’s not entirely true. Shapeshifting plays a role in the way I navigate through the world and in my practice.

I understand. Knowing how important it is to shapeshift, how would you describe your identity? Does that feel that it's at the heart of your work?

Yes, my practice encompasses the many layers of who I am, but I am more focused on the deceptive ways race operates as a construct in our everyday lives (past and present). I am Genevieve Gaignard. Yes, I am the daughter of a Black man from Louisiana and a white woman from Maine, a biracial Black woman who looks White to many I encounter. I am the sister to three brothers, an aunt, a friend, and an artist. I’m also anxious, sarcastic, sensitive, and a lot of other things. But, there is something beyond the individual experience of my identity that shapes the work. I am responding to fabricated representations of what my Blackness symbolizes in our society.

I imagine that many mixed-race people, as I am myself, are so fulfilled by your work. especially with ambiguity in representation. Is that a motivator for you?

I really appreciate you saying that. I started making this work to understand my own ambiguity as I move through the world, and there’s comfort in knowing others feel seen. Some people feel a sense of validation or recognition with the work, and others can be confused or completely oblivious to the message. I guess that means ambiguity is inherent to my practice. Right now I’m motivated by letting go of the anxiety around how I (over)think I’m supposed to show up in the world.

Have you discovered anything about self-identity that has been surprising in regards to yourself, or even, from others?

What I’m discovering is that I don’t always have to perform my identity in the same old obvious ways. And there’s been conversations around my work that make me feel like I have to constantly do that. It’s an exhausting and confusing facade that I’m trying to shed. I’m not ashamed of my identity or who I am, I just don’t want to talk about it in this way anymore. At this point, I no longer want to convince or remind people of my “identity.” Who I am is steeped into my being and that is absorbed into the work. If I’m less focused on convincing an audience and just allowing myself to be. I hope the work speaks in more profound ways.

I love that. Part of your practice is collecting racist and anti-Black objects that appear within your art. I'm curious how often these are items you have to seek out, or if these kinds of objects are still very prevalent.

Yes, part of my practice involves sourcing objects that can be referred to as “Black Americana.” While I wasn’t necessarily seeking out Black Americana collections, many of these objects were in my periphery growing up. In my own process of sourcing objects, I’ve often come across racist advertisements, figurines, toys, kitchenware, and other random everyday objects of the late 19th-early 20th century that use images that embodied racial stereotypes or caricatures. The Mammy figurine, which is often used in my work, was produced until the second half of the 20th century by multiple manufacturers. They were one of the most popular collectible items from the 1920s to the 1950s, found in homes all over America. Eighty years isn’t that long ago. If you walk through a Sunday flea market or any antique shop, I’m sure you’ll see some form of racist or anti-black objects in their collections. I am not actively looking for these objects, they find me. And now I can’t unsee them.

You play a lot with stereotypes that are attached to both Blackness, but also womanhood, glamor, and beauty. Is there a line there that you don’t want to cross?

I think I’m still figuring that out. I tend to play on the edge of making folks comfortably uncomfortable. But at times, I feel like my work isn’t risky enough.

I imagine that many people (cough, cough, White people), may get transfixed on the “fun” or “ beauty” that's the Trojan horse in your work. How do you mitigate that? Does this feel like feedback or just a “shrug and eye roll”?

It’s funny because so much of my energy is poured into the things I make, and the work is often met with “Oh, this is so beautiful.” But I find I’m so focused on the darker context of my work that these fixations of beauty become veiled for me. I can’t always see it, but I know the materials I use to create this allure. It’s complicated for me to fully describe. Beauty seems fleeting and the underbelly of the work is not. So that’s what I’m up against. I don’t know if it’s necessary for the message to always hit you over the head; yet if one feels compelled to spend a little more time with the work, the veil of beauty starts to dissolve.

Your work unabashedly confronts racism and racist histories. I imagine working with that day in and out can become triggering and overwhelming. Do you have any sort of ritual to prepare yourself, to kind of hold yourself safe?

You know, my last solo exhibition titled Strange Fruit was a really tough show for me to produce. I feel like I was trying to connect a tender point of American history with the frustration of wanting White folks to try to feel the grief and violence acted out on Black people which they cannot fully contend with. The show didn’t have the impact I expected and I had to check in with myself. For me, the work can be triggering, though it was necessary to make this body of work. The emotions that it brought up were overwhelming and that feeling hasn’t yet ended.

It's been a year since Strange Fruit and I’m still figuring things out. I lost a feeling of safety after the show, or maybe I never had it to begin with. But life has been throwing moments at me to push the boundaries of how I show up. And with that, I am trying to build new rituals that bring me peace in my own essence.

“I tend to play on the edge of making folks comfortably uncomfortable. But at times, I feel like my work isn’t risky enough...”

When you begin a new work, where does that idea usually stem from? Is it finding an object? Or do you have an idea in your mind and then seek out objects that fulfill that?

New work stems from different sources. I am responding to happenings in the world. Sometimes it starts with an object or an image that gets my attention. Perhaps a childhood memory or a conversation I had with someone. The most recent works I’ve made are for an upcoming show at The Frist Art Museum, Multiplicities: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage. At the time of creating these works, I leaned into Tarot cards, which helped me navigate my emotions over the last year and gave me inspiration to create these new collages.

How do you think your work has evolved the most over your career? What events, reflections, feedback, or advice instructed that shift?

My work has lived with me and evolved alongside every step in my life: growing up in a small mill town with no diversity, pursuing formal art education, moving to Los Angeles, losing my niece in a tragic accident, the pandemic and national uprisings, and even my last show.

Who are some of the artists who have inspired you along the way?

My influences are all over the map from Diane Arbus to Arthur Jafa, Luther Vandross, Betye Saar, Blk Mkt Vintage, Vanessa German, Umar Rashid, and Ghetto Gastro, to name a few. Being a panelist for the Yale MFA Photography cohort has also been a great source of inspiration. Even though I’m in a position to offer guidance to the cohort, I feel like I’m learning so much from them and the other panelists. Also a special shout out to the artists I’m currently in residency with, Kenny Rivero and Papay Soloman. They are two dope humans who make me laugh while at the same time keeping me in check and have helped me reflect on the artist I want to become.

What are you working on now? Anything exciting you can share?

Being in residency is giving me the time to work on a few exciting upcoming projects. I can say that collaboration is a big part of where the future is heading, and I am loving all of what is unraveling for 2024.

Genevievegaignard.com // @creativecurvyginger // This interview was originally published in our Juxtapoz FALL 2023 Quarterly